eBook - ePub

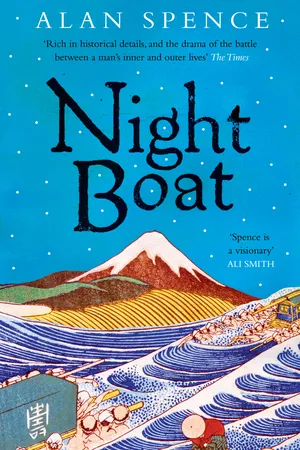

Night Boat

About this book

"One of the best Scottish writers of our time" offers "a fictional re-creation of the life and teachings of the 18th century Zen master Ekaku Hakuin" (

Scotsman).

On the side of a mountain in eighteenth-century Japan sits a man in perfect stillness as the summit erupts, spitting fire and molten rock onto the land around him. The man is Hakuin. He will become the world's most famous teacher of Zen—and this is not the first time he has seen hell.

In Night Boat, acclaimed author Alan Spence presents a richly imagined chronicle of Hakuin's life. On his long and winding quest for truth, Hakuin will be called upon to defy his father, face death, find love, and lose it. He will ask, what is the sound of one hand clapping? And he will master his greatest fear.

This beautifully rendered novel "presents a vivid and comprehensive picture of Japanese society, and every chapter is also full of incidental beauties, little stories and parables, short poems, snatches of lovely description, gnomic conversations, and acute observations" ( Scotsman).

"Spence is a visionary." —Ali Smith, award-winning author of How to Be Both

"Rich in historical detail, and the drama of the battle between a man's inner and outer lives." — The Times, UK

On the side of a mountain in eighteenth-century Japan sits a man in perfect stillness as the summit erupts, spitting fire and molten rock onto the land around him. The man is Hakuin. He will become the world's most famous teacher of Zen—and this is not the first time he has seen hell.

In Night Boat, acclaimed author Alan Spence presents a richly imagined chronicle of Hakuin's life. On his long and winding quest for truth, Hakuin will be called upon to defy his father, face death, find love, and lose it. He will ask, what is the sound of one hand clapping? And he will master his greatest fear.

This beautifully rendered novel "presents a vivid and comprehensive picture of Japanese society, and every chapter is also full of incidental beauties, little stories and parables, short poems, snatches of lovely description, gnomic conversations, and acute observations" ( Scotsman).

"Spence is a visionary." —Ali Smith, award-winning author of How to Be Both

"Rich in historical detail, and the drama of the battle between a man's inner and outer lives." — The Times, UK

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

SEVEN

OHASHI

Among the increasing number of lay followers who came to Shoin-ji to listen to my outpourings of venomous wisdom was a middle-aged businessman, Layman Isso. He had married late, and I knew nothing about his wife. Then one day he asked if she could come with him to hear my teachings.

Of course, I said. By all means.

She is an extraordinary woman, he said, and her story is a remarkable one.

I assumed he was just besotted with her, but the following week he brought her to the temple, and it was clear she was indeed out of the ordinary. Her name was Ohashi and she was perhaps in her thirties, classically beautiful in a way that would still turn men’s heads, even dressed as she was in plain simple robes. But more than that, there was an inwardness, a seriousness about her. It seemed to me she had known great sadness, great struggle, had won through to an acceptance and a gratitude at finding herself here.

One evening, after I had given a brief talk on the Blue Cliff Record, I noticed her sitting very still, deep in meditation. I asked her and her husband to stay behind and join me for tea, and I asked if she would mind telling me her story.

She composed herself, glanced at her husband who nodded encouragement. Then she began, slowly at first, a little uncertain.

My father was a high official serving the Daimyo of Kofu, she said. We lived comfortably in splendid surroundings. We had servants attending to our every need. Then our circumstances changed.

She paused a moment, her voice wavering.

That is the nature of circumstances, I said, pouring her more tea. She sipped it and continued.

My father was forced to leave the Daimyo’s service. It was over a trifling matter, but a matter of honour. So he had to go.

Of course.

He was forced to live as a ronin, a masterless samurai. We went to Kyoto where we knew nobody. We had nowhere permanent to stay and moved from place to place.

This is how we live on earth, I said.

Our money ran out, she said. My mother and father grew haggard and thin. My mother fell ill. I couldn’t bear to watch her fade away. Then I realised there was something I could do.

Once again she paused. Again I filled her cup but she stared at it, lost in remembering.

I was young, she continued at last. I understood men found me beautiful. I said they could sell me into service as a courtesan.

Her husband Isso cleared his throat, shifted on his cushion. Ohashi glanced across at him, gave a faint smile, continued.

My mother said she would rather starve to death. She said any parents who did such a thing to their child were worse than animals. My father remained silent. His mouth was a grim, straight line. His silence filled the room. It was difficult to breathe. Eventually I spoke again. I said any child who watched her parents starve was less than human. I said I would do this thing, it would only be for a short time, till our fortunes changed and we could be together again as a family.

My mother wept and said it was contrary to the Buddha’s law. From somewhere, born of desperation, I found the right words and grew eloquent. I said the Buddha spoke of Expedient Means, used to spread his wisdom. This course of action would simply be expedient, a necessity in the short term, and perhaps this too would be a kind of wisdom.

My father left the room then, his face set, an angry mask. I heard him let out a great roar of rage and pain and some piece of furniture clattered to the ground. When he came back in, his expression was blank, desolate.

You are right, he said. There is no other way.

A week later I was handed over to the madam in a Kyoto teahouse, to begin my training.

She looked at the tea in her bowl going cold. The light in the room was fading, and one of the young monks approached and asked if he should light the lamp. I thanked him and asked if he might also bring more hot water to replenish the tea. This he did, with a brisk efficiency, then he bowed and removed himself.

I waited till Ohashi seemed ready to resume her tale, nodded to her.

This is a story of great sacrifice, I said. Such a thing is rare in one so young.

She bowed.

Necessity, she said. Expediency.

A kind of wisdom.

At first, she said, I convinced myself it was not so bad. The madam, in her way, was kind. She did not ask me to . . . be . . . with many men. And she was very selective, chose only men who would be gentle and considerate.

Again Isso-san tensed and shifted on his cushion, cleared his throat loudly. Again she glanced across at him, reassuring.

And of course, she said, I received an education. I learned to play the koto, I studied poetry and calligraphy . . .

She plays beautifully, said Isso. Her calligraphy is fluid and expressive. Her waka poetry is sublime.

She smiled at him.

You are too kind.

So it was all very . . . refined, I said.

Yes.

But still . . .

Yes, she said. Still.

Her face was half in shadow, the lamplight flickering in the room. But I could see the deep sadness in her eyes, the set of her mouth. She spoke quietly.

It was a kind of hell, she said, however comfortable. I had no freedom, no life of my own. I had been cast out of paradise, and the worst of it was remembering my former happiness. I grew wretched and fell ill. The madam sent for the finest doctors she knew. Some of them were her customers! But none of them could help me.

Some illnesses are beyond cure, I said.

This was a sickness of the heart, she said. Born of despair.

So how did you conquer it? I asked.

She smiled.

One of my . . . patrons . . . was a young man from a noble family who had studied with a Zen master.

Not one of those do-nothing layabouts, I hope.

She looked confused.

I have no idea, she said.

Forgive me, I said. I was just launching into a familiar rant! Now, please, continue.

He said there was a cure, and its name was detachment. I simply had to detach myself from my seeing, hearing, feeling and knowing.

Simply, I said.

He said, Concentrate your full attention on only two questions. Who is it that sees? Who is it that hears? If you can do this in the midst of your everyday activities, whatever they may be, then your inborn Buddha-nature will come to the fore. This is the only way to go beyond and free yourself from this world of suffering.

Sound advice, I said, but not such a simple matter to put into practice.

I did my best, she said, and it definite...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Also by Alan Spence

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- One

- Two

- Three

- Four

- Five

- Six

- Seven

- Eight

- Acknowledgements

- The Pure Land

- Poetry by Alan Spence

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Night Boat by Alan Spence in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Historical Fiction. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.