eBook - ePub

A Business of Some Heat

The United Nations Force in Cyprus Before and During the 1974 Turkish Invasion

This is a test

- 512 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Business of Some Heat

The United Nations Force in Cyprus Before and During the 1974 Turkish Invasion

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The island of Cyprus, long troubled by inter-communal strife, exploded onto the world stage with the Athens-inspired coup against President Makarios and Turkey's invasion that followed. This resulted in the partition of the Island, which was policed by UNFICYP under the most testing conditions. These dramatic events are described here for the first time in this book which examines the political and military background, the Greek and Turkish forces and the make-up and operations of the multi-national UN Force. The difficult situation was further complicated by the Yom Kippur War and the rapid despatch of a significant part of UNFICYP to Egypt.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access A Business of Some Heat by Francis Henn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire moderne. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

HistoireSubtopic

Histoire modernePART ONE

THE ROSY REALM OF VENUS

Fairest isle, all isles excelling,

Seat of pleasures, and of loves;

Venus here will find her dwelling,

And forsake her Cyprian groves.

Seat of pleasures, and of loves;

Venus here will find her dwelling,

And forsake her Cyprian groves.

John Dryden: Song of Venus.

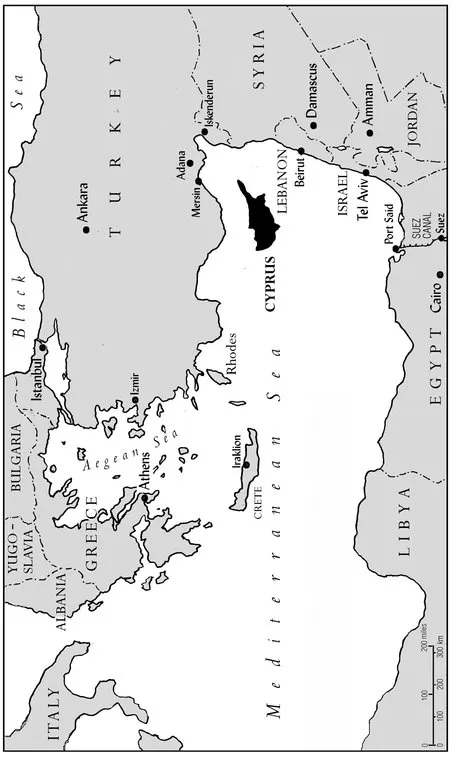

CYPRUS and the EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

CHAPTER ONE

SEEDS OF CONFLICT

Different invasions weathered and eroded it, piling monument on monument. The contentions of monarchs and empires have stained it with blood, have wearied and refreshed its landscape repeatedly with mosques and cathedrals and fortresses. In the ebb and flow of histories and cultures it has time and again been a flashpoint where Aryan and Semite, Christian and Moslem, met in death embrace.

Lawrence Durrell: Bitter Lemons.

The hot summer of 1974 brought a watershed in the long and often unhappy history of the island of Cyprus. Invasion and bloody conflict were no new experiences for its peoples, who down the ages have suffered more than their fair share of these. But never before had a de facto partition been imposed upon the island, with tens of thousands ruthlessly uprooted from homes, property and livelihoods in the heartless process that later became known as ‘ethnic cleansing’. It was the consequence of actions by the armed forces of foreign powers acting sometimes with a ferocity that echoed the inhumanity of earlier centuries and with scant regard for the internationally recognized status of the Republic of Cyprus as an independent sovereign state and member of the United Nations.

The seeds of the Cyprus problem were sown deep in time; its history is complex and its ramifications wide. If the part played by the UN Force in the years leading up to that fateful summer is to be seen in clear perspective, an understanding is necessary of the main factors that lie at the heart of the problem, the circumstances in which the Republic was given birth in 1960, the events that led to the deployment of UNFICYP four years later, and the influences exerted by external interests and pressures.

A wry story circulating in Nicosia told of the United States government’s misplaced gesture of goodwill in donating a map of the world so projected as to place Cyprus at its centre, thus serving to confirm Cypriots in their self-centred delusion that it was, indeed, their small island around which the remainder of mankind revolved. Cyprus certainly has been the focus for inordinate international attention in recent decades. Why does this small island, tucked away in the north-east corner of the Mediterranean and with a population of a mere 632,000 people, generate such concern? As a Canadian journalist once remarked:

It’s ridiculous that so few people should take themselves so seriously. Even worse is that so many others also take them seriously. When President Makarios turns up at the Commonwealth Heads of Government Conference in Ottawa next month, “Your Beatitude” will be heard on every side from people who wouldn’t turn their heads to greet the Mayor of Vancouver who, if not a Beatitude, at least represents a million people.1

Sadly the troubles of the island’s long-suffering peoples are not to be dismissed as easily as such light-hearted words suggest.

The heart of the problem of Cyprus, renowned as the birth-place of Aphrodite, Goddess of Love and Beauty, and for long fondly portrayed by romantics as an Arcadian land peopled by friendly folk who pass their days in watching their flocks, tending their vines or gossiping in the shade of village coffee-shops, lies in its geographic situation in the Levant, for it has been this that throughout recorded history has conferred strategic importance on the island. Powers seeking to dominate the region found it necessary to occupy Cyprus for military reasons (and sometimes also for the commercial advantages afforded by its situation and mineral resources). Never strong enough to defend itself, the island was fought over and colonized by a succession of foreign powers from the Mycenaeans, who crossed from the Greek Peloponnese in the 14th Century BC, to the Turks, who in 1571 AD savagely ejected the Venetians and ruled for the next three hundred years. In 1878, in consequence of Disraeli’s secret diplomacy, the administration of Cyprus – his ‘Rosy Realm of Venus’ – passed to Britain, although nominal sovereignty remained with Turkey.2

The island’s importance has always been a reflection of contemporary interests. For the Venetians Cyprus was an outpost affording protection for their lucrative commerce with the Levant and support for the Crusades. The Turks saw Venetian domination as an intolerable threat to the interests of the Ottoman Empire and to Muslims making the pilgrimage by sea to the holy city of Mecca. As Ottoman power declined, so British concern grew to curb Russian expansion and its threat not only to Asia Minor and the Dardanelles but also to British imperial interests in India and the Pax Brittanica of the 19th Century. After eight decades of rule by Britain the emphasis changed yet again with British loss of Empire, the growth of Soviet power and the clash of East-West interests as reflected in the Cold War. The ending of the latter has changed yet again but has not lessened the strategic significance of Cyprus, especially for Turkey, in the troubled world of today.

A glance at the map serves to confirm how the island lies close under the coast of Anatolia, thus commanding the approaches to Turkey’s southern ports and airfields.3 Small wonder if Turkish strategists see Cyprus in terms of their country’s defence. While three centuries of rule over the island and the well-being of Turkish Cypriots may be potent factors in Turkish minds, they take second place in the Turks’ cold calculations of their national strategic interest.

Their view has long been sharpened by concern (which common membership of NATO has never allayed) of a Cyprus dominated by or, worse, united with the traditional enemy, Greece – a concern voiced by Mr Zorlu, Turkey’s Foreign Minister, when speaking in London as long ago as 1955:

All these south-western ports are under the cover of Cyprus. Whoever controls this island is in the position to control these Turkish ports. If the Power that controls this island is also in control of the western [Aegean] islands, it will effectively have surrounded Turkey.4

His words were echoed by Foreign Minister Erkin speaking at Lancaster House, London, in 1964. Stressing the strategic importance to Turkey of Cyprus, which he asserted had to be seen geographically as a continuation of the Anatolian peninsula, he concluded:

All these considerations clearly demonstrate that Cyprus has vital importance to Turkey, not merely because of the existence of the Turkish community in Cyprus, but also on account of its geo-strategic bearing.5

A Turkish academic has expounded an even broader view:

The geo-political situation of Turkey and the outlook of the countries encircling her in the north are such as to force Turkey to keep secure her southern defences. Consequently Cyprus maintains its vital importance . . . as far as Turkey is concerned.6

Statements such as these (and many others in the same vein made since) leave no room for doubt that for Turkey the overriding importance of Cyprus is strategic, and that protection of the rights of the Turkish Cypriot minority has been a secondary, though important, consideration.

Asked in 1974 how Britain viewed Turkish interest in Cyprus, Field Marshal Lord Harding of Petherton, who had been Governor of Cyprus from 1955 to 1958, replied:

The geographical distance between Cyprus and Turkey determines the extent of Turkish interest in Cyprus. Beyond the proportion of the population of Cyprus that is Turkish and in whose future Turkey is definitely interested, the country could not remain indifferent to the future of an island so close to its shores. . . . We did not create Turkish interest in Cyprus. It was always there. And it was quite right and just and legitimate for Turkey to show such interest in Cyprus.7

The Cyprus problem cannot be understood without recognition of these fundamental realities.

During the eight decades of British rule there was growing Greek Cypriot agitation for enosis (union of the island with Greece) and consequential mounting Turkish concern. The more Greek Cypriots clamoured for this, the louder Turkey warned that this would be met by taksim (partition of the island, with a Turkish area annexed to Turkey), a development sometimes referred to as ‘double enosis’. The proximity of Turkey and its military power lent credibility to this warning, although many on the Greek side failed to recognize this until it was too late. The granting of independence to Cyprus in 1960 under a Constitution which expressly forbade for all time the island’s partition or its union with another state brought temporary respite, but, when three years later that Constitution broke down before its ink was properly dry, Turkish fears that the Greek majority was bent on enosis were revived. Turkey was determined to forestall any such development and when, ten years later, the ideal opportunity to do so presented itself, it acted swiftly to secure physical control of all northern Cyprus.

The chequered past of Cyprus has given rise to the second main ingredient of the problem – ethnic differences in the population. Until the arrival of the Turks in the late 17th Century the legacy of history had been a population in which Greek influences predominated. The Greek language, together with a Greek cultural tradition, to which Christianity in the Orthodox form was added in early days, combined to create an indigenous people that felt itself to be Greek in character. These, the Greek Cypriots, saw Greece as the mother-country, for which by the late 19th Century a strong emotional attachment had developed and with which political union became a growing aspiration. Following the grant of independence in 1960 such emotions were tempered by realization of what such union might entail; for many the prospect of subjection to the repressive military dictatorship which seized power in Athens in 1967 was especially unappealing. Nonetheless, the dream of enosis remained an ideal embedded in Greek Cypriot emotions, with few daring not to pay at least lip service to it. Makarios himself epitomized this attitude, although latterly sufficiently a realist to warn his community that, so long as Turkey was opposed, enosis was unattainable without risk of simultaneous taksim.

Greek influences had taken root too deeply to be changed by the arrival in 1571 of the conquering Turks, but that historic event injected a critical new element into the ethnic mix of the population. More than 30,000 soldiers of Lala Mustafa’s victorious army were given land and encouraged to settle in Cyprus, and were augmented during the subsequent 300 years by immigrants from Asia Minor. Thus was the Turkish Cypriot community created, and thus were sown the seeds of the island’s 20th Century intercommunal problems. Although Turkish Cypriots always constituted a relatively small minority (in 1974 they formed only 18% of the population as compared with the 78% Greek Cypriot majority8), differences of language, religion and culture were insuperable obstacles to full integration of the two communities. Turks continued to speak Turkish, to adhere to Islam, to maintain Turkish customs, to educate their children in the Turkish cultural tradition and to refrain from intermarriage with other ethnic groups. For them Turkey was the mother-land to which they looked for political support, economic help and, ultimately, military salvation.

Settled over all the island without discernible pattern, the Turks clung together in the all-Turkish quarters of towns and mixed villages or in exclusively Turkish villages. With the passage of time political, economic and social factors tended to accentuate rather than diminish divisions between the Greek and Turkish communities. These reached their deepest immediately before and after the grant of independence, when Turkish fears of enosis and submersion of the minority in the vaunted concept of a ‘Greater Greece’ were at their most acute. Experiences at the hands of their Greek Cypriot fellow citizens when intercommunal violence flared left them in no doubt that their fears were well founded. Small wonder if some preferred to describe themselves as ‘Cypriot Turks’.

The secular power of the Cypriot Orthodox Church constitutes a secondary, but influential, thread running through the fabric of the island’s more recent history. The Church achieved autocephalous (self-regulating) status as a member of the Eastern Orthodox Church as early as the 5th Century, when the Ethnarch of Cyprus was accorded the rights, exercised to this day, to carry a sceptre, wear ceremonial purple and sign his name in red ink. Although the Church’s power declined during the four centuries of Lusignan and Venetian rule, during which the Ethnarch was removed and the authority of Rome imposed, paradoxically the advent of the Muslim Turks saw it restored and enhanced. This was because the Turks, whose arrival was greeted by the Cypriots as a welcome release from grinding Venetian oppression, at once set about rooting out all vestiges of the Roman Church, identified in Ottoman minds with Venice. Roman clerics were expelled, cathedrals were converted into mosques and the Cyprus Ethnarch was restored and recognized by the Turks as both the spiritual and the temporal leader of Eastern Orthodox Greeks on the island, this being in conformity with administrative practice in the Ottoman Empire, by which its Christian subjects were ruled by their own prelates. The Archbishop and his subordinate bishops thus became established as the recognized civil administrators and spokesmen for the Greek community. A consequence, however, was to perpetuate the divisions between Greeks and Turks on the island, with the latter looking across the water to Turkey for the conduct of their community’s affairs.

British rule, while generally refraining from interference in ecclesiastical matters, achieved some progress in lowering the intercommunal barriers, but did little to promote a common Cypriot identity. A set-back came in 1931, when growing Greek agitation for enosis led to riots in which Government House was burnt down.9 British reaction was firm – repressive measures included deportation of two bishops and others seen as ring-leaders. Although these measures were relaxed progressively before and during the 1939 – 45 War when Cypriots of both communities rallied to the British cause, in the immediate post-war years enosis remained as distant a prospect as ever, in spite of much Greek political manoeuvering.

It was the rise in 1950 of a new, young and forceful Ethnarch, Archbishop Makarios III10, that gave fresh impetus to the cause. A passionate advocate of enosis, he sought to achieve this by securing, as a first step, the right of self-determination for the peoples of the island (in practice the Greek majority) in confident anticipation that at the Church’s bidding they would then opt for enosis. His activities quickly established him both as ecclesiastical and political leader of the Greek community to a degree reminiscent of the centuries of Ottoman rule, but simultaneously served to sharpen once more the divisions between Greek and Turk on the island, with the latter increasingly looking to mother-land Turkey for support and protection.

The power of the Cyprus Orthodox Church reached its zenith in 1960 with the election of Archbishop Makarios as the new Republic’s first President, an office he held in parallel with that of Ethnarch until his death in 1977.11 Since, uniquely in the Christian world, the laity in Cyprus take part in the election of their Archbishop, his position was doubly strong. Although the religious divide between the island’s communities has not in itselfbeen a prime cause for discord,12 it has tended to exacerbate other differences, rendering it all the more difficult for the Greek Christian majority and the Turkish Muslim minority to reconcile divergent attitudes to the constitutional and other problems that in recent years have bedevilled their contentious island.

CHAPTER TWO

INDEPENDENCE – THE FALSE DAWN

The achievement of independence, and with it the lifting of the controlling and restraining influence of the colonial power, had the effect of intensifying the mutual distrust and fear ingrained in the two communities and of aggravating their intransigence to each other.

Sir Lawrence McIntyre: ‘Cyprus as a United Nations Problem’, Australian Outlook, April 1976.

The struggle which failed to win enosis but led instead to independence has been well chronicled by others1. It was waged on two fronts: externally by pressures exerted at international level in the course of which, in the face of British insistence that Cyprus was the exclusive responsibility of the United Kingdom, both Makarios and the Greek Government sought to involve the United Nations, not least because they saw this as affording a safeguard against military intervention by Turkey; and internally by armed insurrection, a bitter and ruthless business in which wounds were inflicted that endure to this day.

The campaign of violence, launched on 31 March 1955, followed the UN General Assembly’s rejection the previous December of Greece’s request2 for a motion concerning the right of se...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- GLOSSARY

- FOREWORD

- PREFACE

- PART ONE - THE ROSY REALM OF VENUS

- PART TWO - THE CYPRUS PEACEKEEPING GAME, 1972 – 1974

- PART THREE - YOM KIPPUR AND OPERATION ‘DOVE’

- PART FOUR - FOOLS BY HEAVENLY COMPULSION

- PART FIVE - A WANT OF HUMAN WISDOM

- PART SIX - CUSTODIAN OF THE ORPHAN CHILD

- POSTSCRIPT

- ANNEX 1 - RESOLUTION 186 (1964)

- ANNEX 2 - UN CHAIN OF COMMAND AND CONTROL AND ORGANISATION OF UNFICYP HEADQUARTERS (JUNE 1972)

- ANNEX THREE - GREEK CYPRIOT NATIONAL GUARD AND POLICE – 1974

- ANNEX FOUR - TURKISH CYPRIOT FIGHTERS – 1974

- ANNEX 5 - BRITISH FORCES IN OR NEAR CYPRUS IN JULY AND AUGUST 1974

- ANNEX 6 - ORGANISATION AND CHAIN OF COMMAND OF TURKISH ‘PEACE FORCE’ JULY-AUGUST 1974

- ANNEX 7

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX