![]()

Introduction

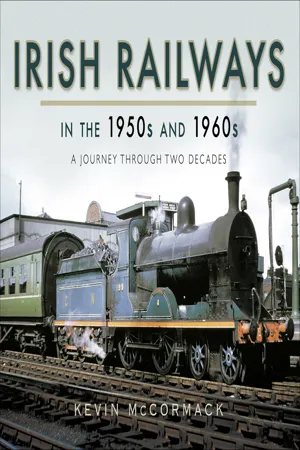

This album of colour photographs depicts the railway scene across Ireland during the final two full decades of steam operation. However, a review of this period would not be complete without the inclusion of a limited amount of non-steam traction, much of it relatively vintage in itself.

This book does not purport to cover the complicated history of Irish standard-gauge and narrow-gauge railways, which has already been fully covered in other publications. The purpose of this volume is to present more than 170 colour photographs that hopefully have never previously been seen in print. Indeed, it serves as a reminder of what many railway enthusiasts in Great Britain were missing across the Irish Sea, given their pre-occupation with the closure of lines under the ‘Beeching Axe’ and the demise of steam on British Railways. The engines and rolling stock in Ireland were generally very ‘British’ in appearance and part of the fascination was that most of the locomotives, even the main line ones, were comparatively small, with several having unusual wheel arrangements for their type; they looked dated (and in many cases were actually old).

A particular anomaly about Irish railways is the standard gauge, which is 5ft 3ins, as opposed to that in Great Britain which is 4ft 8½ins, thereby requiring any stock transferred between Great Britain and Ireland to be regauged. The narrow gauge was generally 3ft. The Irish railway companies referred to the 5ft 3ins gauge as broad gauge, but I have taken the view that the only broad gauge in Ireland was the Ulster Railway’s short-lived 6ft 2ins gauge, so in this book I refer to the Irish gauge as standard gauge. In 1836 the Ulster Railway was authorised to build to a gauge of 6ft 2ins, and constructed their line from Belfast Great Victoria Street to Portadown to this gauge, whereas the Dublin and Drogheda Railway intended to use 5ft 2ins for economy reasons. Clearly, the line from Belfast to Dublin needed to have the same gauge to operate efficiently, so a compromise gauge of 5ft 3ins (hardly a compromise, some would say!) was decreed by Parliament and the Ulster Railway had to replace its broad gauge.

It is worth mentioning that the island of Ireland, consisting of thirty-two counties, used to be part of the United Kingdom. Partition occurred in 1921, when Northern Ireland was created, and a separate Irish Free State (now the Republic of Ireland) was established in the following year. The Free State controlled twenty-six counties, whereas the other six counties (Antrim, Armagh, Down, Fermanagh, Londonderry and Tyrone) remained part of the Union. Over the years there has been much restructuring of the railways on both sides of the border and the most relevant changes are summarised next.

In 1925 the various railways operating exclusively in the Free State were grouped into Great Southern Railways (GSR), and those operating entirely in Northern Ireland were already mostly integrated into a body known as the Northern Counties Committee (NCC) owned by England’s Midland Railway, which was superseded, following the railway grouping in 1923, by the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS). GSR was taken over by the newly formed Coras Iompair Eireann (CIE) in 1945, and the Ulster Transport Authority (UTA), having taken control of the Belfast & County Down Railway (BCDR) in 1948, subsumed the NCC in 1949, following fifteen months of ownership by the British Transport Commission. For completeness, CIE ceased to be an operating company in 1987 and the Republic’s railways are now run by a subsidiary, Iarnrod Eireann (Irish Rail). UTA’s railway interests were transferred to a new body, Northern Ireland Railways (NIR), in 1968 and now branded as Translink.

The partition of Ireland raised the question of how to deal with the various railways that straddled the border. Three of these are covered in this book: two standardgauge railways (the Great Northern Railway (Ireland) (GNR(I)) and the Sligo, Leitrim & Northern Counties Railway (SLNCR)) and one narrow-gauge (the County Donegal Railways Joint Committee (CDRJC)). The GNR was a favourite of railway enthusiasts for several reasons: it was a mainline operator whose services included the important Belfast–Dublin line, its passenger locomotives were painted sky-blue and it had two tram systems: the electric Hill of Howth Tramway in Co Dublin and the Fintona horse tram in Co Tyrone, Northern Ireland. These three railway companies were excluded from the nationalisation that occurred in Northern Ireland and the Republic in 1948 and 1950 respectively.

However, the GNR(I) suffered financial failure in the early 1950s due to increased road competition despite a modernisation programme; it announced that it was closing. This galvanised the two governments into action, culminating in de facto nationalisation by the creation of a joint governmental Board (the GNR Board) in 1953 to run the company. Outwardly, this allowed the GNR(I) to continue comparatively unchanged for a few more years until the Board was disbanded on 1 October 1958. At that point the routes and assets including the locomotives and rolling stock were divided between the UTA and CIE, although GNR(I) livery remained in evidence for a time. The division of the GNR(I) had, however, a significant impact on both sides of the border. CIE had all but abandoned steam in 1958 in favour of diesels and then found itself with an expanded rail network and some eighty extra steam locomotives, resulting in steam lingering on in the Republic until 1963. In Northern Ireland, which adopted an anti-railway approach at that time, several lines had been closed in the 1950s and the process continued with much of the inherited ex-GNR(I) network. Closure seemed to be favoured over modernisation, with the consequence that Northern Ireland was behind the Republic in terms of the steamto-diesel transition and did not withdraw its last steam locomotives until 1970.

By this time, the Railway Preservation Society of Ireland (RPSI), formed in 1964, was gaining momentum and running railtours throughout Ireland, as it continues to do today using its fleet of preserved locomotives. Other preservation societies have also sprung up across Ireland such as the diesel-orientated Irish Traction Group and some heritage railways, with the result that a reasonable cross-section of steam and diesel motive power survives, although there are some sad omissions.

As for the other cross-border railways featured in this book, the CDRJC was jointly run by the GNR(I) and the Midland Railway-owned NCC (later UTA) and closed in 1959. The SL & NCR, a private company latterly subsidised by the two governments, closed in 1957.

This is a view from the footplate of GNR(I) U class No.199, Lough Derg, as it heads north out of Dublin on its way to Belfast in July 1959. (Donald Nevin)

In terms of organising the photographs in this book, it was tempting to put GNR(I) locomotives and workings into a separate section, distinguishing these from CIE and UTA/NIR activities. However, most of the images of GNR(I) locomotives and trains date from the cessation of the GNR Board in 1958 and are therefore operated by the UTA or CIE, even though many locomotives still have the appearance of belonging to the Board. The book has been divided into two sections, based on whether the photographs were taken in Northern Ireland (where the main body of the book starts) or the Republic of Ireland. GNR Board and ex-GNR(I) locomotives and trains therefore appear in either section, depending on the location of the picture. With regards to the CDRJC and the SL&NCR, since most of the images of these cross-border railways were taken in Northern Ireland, and so that is the part of the book where they can be found. Northern Ireland images start at Belfast and proceed roughly in an anti-clockwise direction as far as Newry. Then we cross the border to Dundalk and move approximately in a clockwise direction through the Republic. An index of locations can be found on the last page...