- 112 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Fishing Industry

About this book

Working with prestigious archives of contemporary photographs, the authors chart the history of Britain's fishing heritage with 120 rarely seen photographs. Fishermen were hardy individuals with a precarious existence dictated by the changing rhythm of the wind and the waves. While at sea, their womenfolk cleaned, salted, pressed and bulked the fish. The fishermen of the East Coast are the last of the hunter gathers, in the later 19th and early 20th century British fishery expanded and exceeded its European rivals to become the biggest fishery in the world. Dwindling fish stocks after the Second World War saw the end of the fishing industry as it had been known, now the trawlers had to make the hazardous voyage to deeper waters. This book celebrates the heyday of the British fishing industry, the people, the processes and the vessels.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter One

Around the Coast in 1900

The heyday of the British fishing industry lasted through sail and steam and boomed towards the middle of the nineteenth century, reaching its peak just before the First World War. This set of photographs provides a snapshot of the fishing industry around the turn of the nineteenth century, from the Highlands and islands of Scotland, around the English coast, into Wales and across the sea to Ireland.

The eventual collapse of the fishing industry led to the end of many traditional ways of life, some of which are illustrated in these photographs. With the loss of traditional ways of earning a living entire communities were changed forever. On a smaller scale these changes had been happening for centuries. As the winds and tides changed the spawning grounds moved and economic forces worked for or against fishing industries on particular stretches of the coast. Fishing has always been a part of the life of those that live on the shores of Britain; an extension of the hunter-gatherer society. The modern fish trade, as it was becoming towards the end of the nineteenth century, was driven to greater success by the railways. Fish provided a cheap source of protein and up and down the country the fish and chip shop became an institution. Although fish is now as expensive as meat, it was once far cheaper and British fish was in great demand across the globe.

The turn of the nineteenth century saw the beginning of the end of small, independent and subsistence fishermen. But it also saw vast industries emerging, particularly along the east coast of Scotland and England, involved in the herring trade. At the peak of the trade before the First World War 8,000 Scottish women descended on Great Yarmouth each year to gut and pack herring. They were accompanied by at least 2,000 men, who would work in the curing houses.

When these photographs were taken, steam power had only been introduced twenty or thirty years earlier. Trawlers operating out of ports such as Aberdeen in the herring industry were amongst the last to adopt steam power. In 1913, for example, a staggering 954 steam drifters left Scotland for the winter herring season off East Anglia. In 1877 steam had been used for the first time to haul trawl nets: it was to mean record catches for a short time.

Line fishing was still being used. They were laid across the tide in the early morning, to be hauled up at night. Some of the lines would have as many as 1,000 hooks on them.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century fishermen had to travel much further to secure their catches. Scottish fishermen on the Firth of Forth set sail in the late spring, heading west. They would make for the north in the summer and by autumn they would be off East Anglia.

Once the fish was caught and brought back to shore the bulk of it was sold at local fish markets, at first on a relatively small scale. Newhaven’s new fish market opened in 1896 and was a centre of commerce, with buyers and fishermen being attracted from all over the east coast.

We begin our whistle-stop tour of the coastline of Britain in Scotland, where perhaps many more unique communities’ ways of life were driven and sustained by the fishing industry. In some cases, as the fishing industry would change and in places disappear, so too would those unique ways of life.

Scotland

These are women of St Kilda, the most remote of the Scottish islands, some forty-one miles to the west of the Outer Hebrides. St Kilda had around forty acres of arable land, on which potatoes, oats and barley were grown. There were a few head of cattle and some sheep. The island had a productive but neglected fishing industry. So isolated was the island that at the end of the nineteenth century mail only arrived two or three times a year. People had been living on St Kilda since at least the Iron Age. The landlords rented the land to the small population and a representative of the landlord collected the rent on an annual visit. Rents were mainly paid in kind, through produce, fish and wool. The main village was Hirta, a simple cluster of thatched stone houses. Whalers and fishing fleets brought supplies to the islanders, but it was the fact that the St Kildans were losing their self-sufficiency and relying on imported food and fuel that would see the end of this way of life.

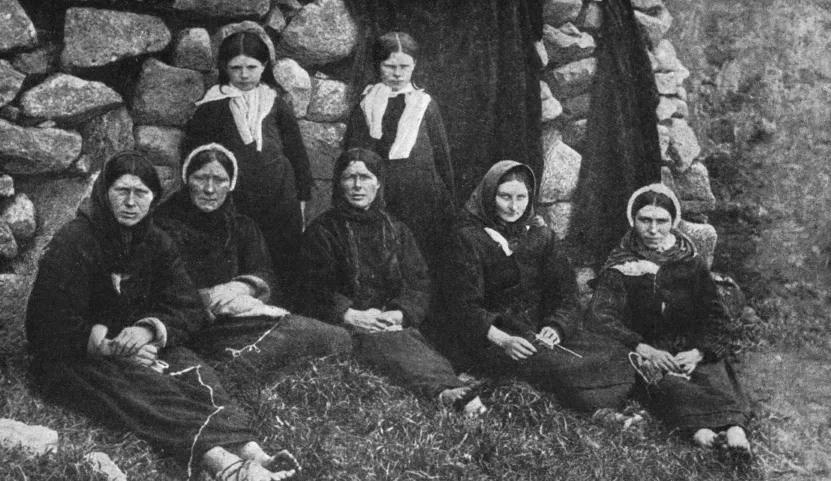

This is another group of women from St Kilda: note that as in the last photograph many of them are barefoot. In 1852 thirty-six of the inhabitants immigrated to Australia, some settling in Melbourne, where there is now a suburb called St Kilda. There was a severe food shortage on the island in 1876 and worse was to come in 1912. Communication was still haphazard, with mail and messages being sealed up in wooden containers and attached to sheep’s bladders to act as a float. By 1930 the thirty-six remaining islanders had had enough and requested evacuation to the mainland.

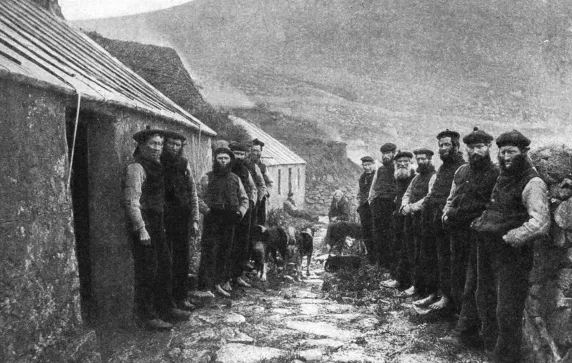

The bearded men of St Kilda are seen here in the main street of the village. At the turn of the century there were about eighty people living on the island. They were Gaelic speaking and, as this photograph shows, life could not have been particularly easy. The absence of timber on the island meant that boats had to be supplied from elsewhere and the island also lacked safe landing places. In any case, there was no means of exporting any fishing catches. Fresh fish and fish liver dishes were eaten all summer and salted fish was one of the mainstays of the winter diet. This was supplemented by seabird eggs and young seabirds.

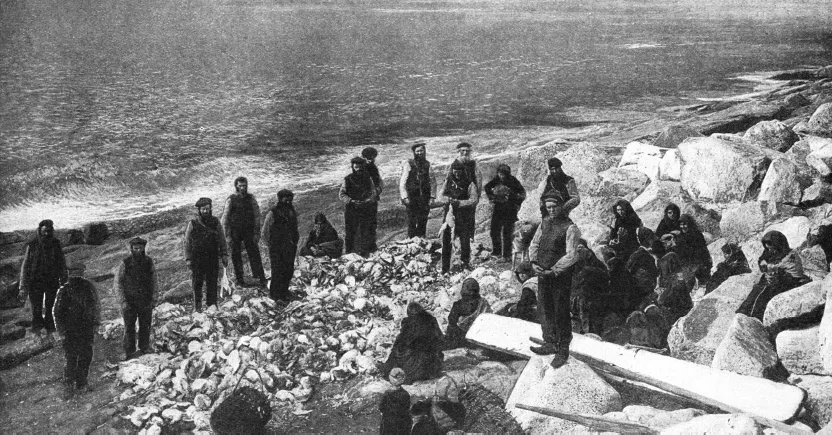

What equates to around half of the population of St Kilda are dividing up a large catch of fulmar in this photograph. These are seabirds, which bred on the cliffs. They were historically bred on St Kilda and spread into northern Scotland during the nineteenth century. The St Kildans were expert cliff climbers and they would eat not only seabirds but a wide variety of other birds, which were chiefly caught with nooses. The island is now a World Heritage site and important seabird breeding ground. It was bequeathed to the National Trust in 1957.

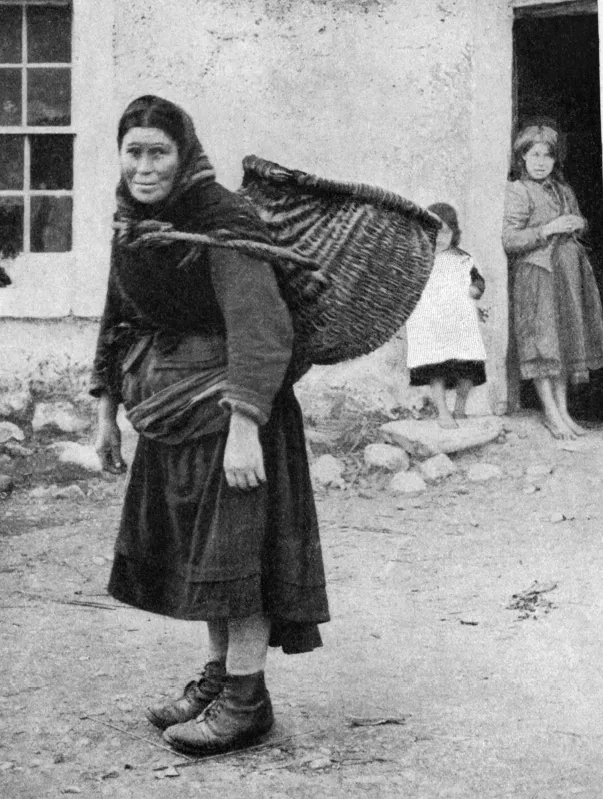

A herring hawker is trudging around the streets of Cromarty (part of which was known as Fishertown), in the Highlands of Scotland, in this shot. Women such as these would fill their baskets with herring as soon as the boats came in alongside the quay. The baskets were strapped across the chest. The women usually wore short skirts, kilted to the waist, and they would be able to carry heavy weights of fish for long distances. Cromarty had been established as a Royal borough by the thirteenth century. It sat at the north end of the Black Isle Peninsula, at the mouth of the Cromarty Firth. In 1772 the town was developed after the estate was bought by George Ross. He had a new rope works and harbour built to help encourage the fishing industry.

A photograph of Fishertown, in Cromarty, can be seen here, with the street leading down to the Cromarty Firth. Shoemaking was another old tradition in Cromarty. To the left of the photograph we can see something of a tradition: a fish hanging, drying on the whitewashed walls either side of the doors. The fishermen’s wives are sitting beside their creels, or baskets of bait. Some are dealing with fish that has just been brought in; others are mending nets, preparing bait or packing herrings into barrels for market.

Two Cromarty women and an old fisherman are preparing mussels as tempting bait here. In Cromarty both net and line fishing was used and the baiting was mainly done by the women. Mussels were used for bait all around the Scottish coast, as were lobworms. The mussels were gathered by women and children and then opened with a short knife. These women are looking over the hooks to make sure that they are securely fastened to the lines. Once they are happy with the arrangement they will then bait the lines. Fish wives often had distinctive clothing: usually warm coats covered striped petticoats, and they would often wear muslin caps.

This photograph was probably taken either on the north Highland coast or on Skye. The boat in the photograph is being launched into an estuary, as the indications appear to be that the men are engaged in salmon fishing. Fishing for salmon in the estuaries was a well-practised technique for at least 500 years. The main way of fishing was by net, or by sweep net. A long net would be released from the stern of a small rowing boat in order to surround the fish and then draw them ashore. The salmon would then be preserved in wooden barrels with salt and then shipped south, some for domestic consumption and the rest for export, particularly to France and Holland. If the weather was good along the east coast some of the salmon could even be transported as far as London raw, without having to be salted. In the spring salmon was boiled and then sealed into small barrels with vinegar. This was known as kitted salmon.

The next stage of the process … The men are now pulling in the net filled with struggling fish whilst small boys watch on as their fathers reap the harvest. In other parts of Scotland ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Images of the Past: Fishing Industry

- Introduction

- Chapter One: Around the Coast in 1900

- Chapter Two: St Ives, 1923

- Chapter Three: The North Sea

- Chapter Four: Wartime and Personal Memories

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Fishing Industry by Jon Sutherland,Diane Canwell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.