![]()

Chapter One

Courtesans and Mistresses

ARGYLL, Margaret, Duchess of 1912–93

Even before becoming the third wife of the 11th Duke of Argyll in 1951, this society beauty was fuelling the gossip columns. The daughter of a Scottish millionaire, partly educated in New York, it was said that she lost her virginity at the age of fifteen to the actor David Niven. What is more well documented is her voracious sexual appetite and penchant for men of all ages and from the entire social strata. She had been engaged to the 7th Earl of Warwick, romanced by a Prince (Aly Khan), by the bisexual George, Duke of Kent – and by Lord Beaverbrook’s son, Max Aitken; but it seems that there were also plenty of one night stands with whoever came her way! Her first marriage (1933–1947) was to Charles Sweeny, an American golfer, producing two children, and she had subsequent relationships with a Texas banker and the curator of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. A woman of eclectic tastes.

Margaret, Duchess of Argyll. (Allan Warren)

It was her taste for adultery and litigation that puts her into this book, however. When the Duke of Argyll sued for divorce in 1963, he introduced a list of eighty-eight men to the court, including government ministers and members of the royal family. The evidence was salacious enough to make all the national newspapers. There was her diary (apparently stolen by the duke) listing the physical attributes of her lovers, as if, according to the Daily Telegraph, she ‘was running them at Newmarket’. First and foremost, however, there were the Polaroid photographs of the Duchess, wearing only three strings of pearls, fellating a man whose head is not in the photographs, and who has therefore never been identified with certainty. Possibly the actor Douglas Fairbanks Junior? Or Duncan Sandys, Winston Churchill’s son in law? Perhaps even the Duke of Edinburgh? The general consensus favoured Douglas Fairbanks, but the (also controversial) Lady Colin Campbell, the Duchess’s step-daughter-in-law, has gone on record as stating that the man was Pan Am executive Bill Lyons … the Duchess herself never revealed the truth, even in her 1975 memoirs Forget Me Not.

The court case lasted eleven days, with the judge summing up the Duchess as ‘a completely promiscuous woman … wholly immoral’. Not unexpectedly, the Duke was granted his divorce, following a judgment that ran to a near novel-length 40,000-plus words, one of the longest in history. The case itself probably cost the Duchess more than £200,000 but it didn’t stop her suing, in the ensuing years, her daughter, her landlord, her bank, her stepmother, and her servants, usually for libel and usually unsuccessfully. The 1970s were full of lavish parties but she was forced, financially, to sell her house in Upper Grosvenor Street in 1978, and took up residence in Grosvenor House, from where she was finally evicted over unpaid rent in 1990, ending up in a nursing home in Pimlico.

The Duchess had been Deb of the Year and one of the Top Ten Best Dressed Women in the World. She had also, as Mrs Sweeny, been immortalised in the words of the Cole Porter song ‘You’re The Top’ – he rhymed her with ‘You’re Mussolini’… and it is Mr Sweeny who is her companion in death, at Brookside Cemetery, Woking.

BELLANGER, Marguerite 1840–86

There are enough notorious French courtesans to fill a book and indeed, French libraries are full of such books. Marguerite Bellanger was a little different, hence her inclusion here. A farm girl, a bit of a tomboy, outspoken, an unsuccessful actress with thick ankles … but Napoleon III, who met her in a park in Vichy in 1863, when she was twenty-three, was attracted by her blonde hair, black eyes, and vivacious personality. It seems they met in the rain, but stories of the meeting vary enormously: she was sheltering; he was sheltering; she offered him a raincoat; he offered her a rug; he was hunting; she was riding … but meet they did and the attraction was obviously instant.

Born Julie Leboeuf, her surname gave rise to unappealing nicknames, hence her change of name once she had escaped from her life of poverty as a laundress. She became a dancer and bare-back horsewoman at a provincial circus, seduced along the way by a handsome lieutenant, until ending up on the stage before she was twenty. But she was not keen on criticism from the Paris audiences, and started on the road to prostitution (sometimes described as a ‘second rank cocodette’) attracting the French C list, for instance, the son-in-law of the President.

Marguerite Bellanger, a bust sculpted by Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse at the Musee Carnavalet, Paris.

The Emperor Napoleon III was of course the supreme catch. She was his last mistress (1863–1865) and said to be his favourite, until she wanted too much influence and spent too much money (such as buying two horses for 25,000 francs), becoming something of an embarrassment. The Empress Eugenie, who had tolerated Napoleon’s previous mistresses, was less tolerant of Marguerite and apparently confronted her, telling her that she was ‘killing’ the Emperor, not that this made any difference.

In 1864, Marguerite had a son, Charles, without naming the father. She may well have falsified the date of his birth to make him more likely to be Napoleon’s son. Regardless of this theory, Napoleon, in his mid-fifties, rather generously, looked after the boy financially, settling property on him as well as on Marguerite. However, once the affair was over, she sold a hotel he had bought for her, keeping some of the land, and a chateau, to ensure she could maintain status and lifestyle. After more, less high profile, liaisons, she went on to marry a Prussian officer in the British Army, William Kulbach, gaining respectability in her thirties. Her ‘confessions’ were published in 1882 and her memoirs, posthumously, in 1890, but neither were salacious enough to be successful. She is said, however, to have provided the career that inspired Emile Zola’s best-selling Nana, published in 1880.

CLARKE, Mary Anne c. 1776–1852

Here we have that classic example of an ambitious actress who found it more profitable to be the mistress of an influential royal. From lowly origins in London, by around 1803 she was entertaining the glitterati of London with the help of twenty servants and three cooks, drinking from wine glasses costing a remarkable two guineas each.

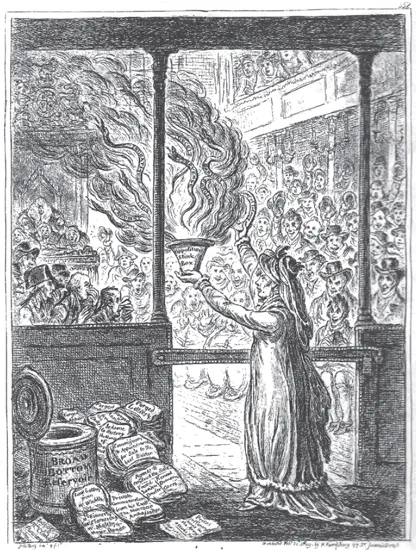

Mary Anne Clarke, from an illustration by Chas. Keene in Our People, Bradbury and Agnew, 1881.

Details of Mary Anne’s parentage and early life are unclear (although her descendant, Daphne Du Maurier, wrote of her as having East London roots) but she certainly married the young, attractive Joseph Clarke in 1794, whom she had apparently met when he was a lodger at her family home. At the time of their marriage, Mary Anne, not yet eighteen, was establishing herself as an actress, playing roles at such popular venues as the Haymarket Theatre in London’s West End. But Joseph, the proprietor of a stone-masonry business, seemed to offer the cultured and rich antecedents Mary Anne craved. Things did not work out as planned, however, because Joseph liked spending money and ended up bankrupt.

Two children later, she left him, with her profession giving her access to a number of subsequent liaisons culminating in a relationship with Frederick Augustus, Duke of York, a probable member of Mary Anne’s smitten audience. It seems that Mary Anne had been promised over £1000 a year by the Duke in addition to the elegant London home and all its trappings, but this allowance was not paid regularly, her resultant debts necessitating a boost to her income. There were always those seeking promotion – military, civil, even clerical, and Mary Anne was happy to take money from them in return for her influence.

Her affair with the Duke turned into a political scandal in 1809, when he was charged with corruption as a result of her activities. The principal witness for the prosecution was listed as: ‘Mary Anne Clarke of Loughton Lodge in the County of Essex, a widow’ although it is not clear whether in fact Joseph was dead. In spite of the way the Duke had shaken her off, exposed her to poverty and infamy and refused her a promised annuity, all damning in the eyes of his public persona, the Duke was acquitted on the charges of corruption. The scandal was the Watergate of Regency London with major coverage in every newspaper.

His ex-mistress’s subsequent threat to publish her memoirs – to pay for her children’s future – resulted in the Duke’s resignation as Commander-in-Chief of the Army and in a legal agreement being drawn up between Mary Anne and her former lover. He agreed that she would receive more than £7,000 (diverse amounts were recorded), a generous annuity for life, and two hundred pounds for each of her children. Blackmail? Some would say so. Adept political manoeuvring would be another interpretation.

Mary Anne could not lay down her pen and libellous publications continued, resulting in her spending nine months in Marshalsea Prison. The only bright spot during this period was the commissioning of her son, George, to the 17th Light Dragoons, thanks to a promise made long ago by the Duke which she had not expected to materialise.

After her release, she was persona non grata. She lived in France for a number of years, in constrained but fashionable conditions and died alone in Boulogne in 1852, her death reported in The Times by the Paris correspondent.

Postscript: While the Grand Old Duke of York had a nursery rhyme dedicated to him (‘He had ten thousand men’ etc …) a rhyme associated with Mary’s downfall is less well known:

‘Mary Anne, Mary Anne, Cook the slut in a frying pan’ (!)

CLEOPATRA 68 BC–30 BC

Perhaps the most famous femme fatale of all, what is known about this fascinating woman is culled from what other people wrote about her; Plutarch, or Julius Caesar’s own works. She was one of the last members of the Ptolemaic dynasty with its roots in incest, treachery and murder. Her father left the kingdom of Egypt to Cleopatra (then seventeen) and his elder son, Ptolemy XIV (eleven) who began their joint reign in 51 BC but who became extremely competitive, both wanting to rule Egypt.

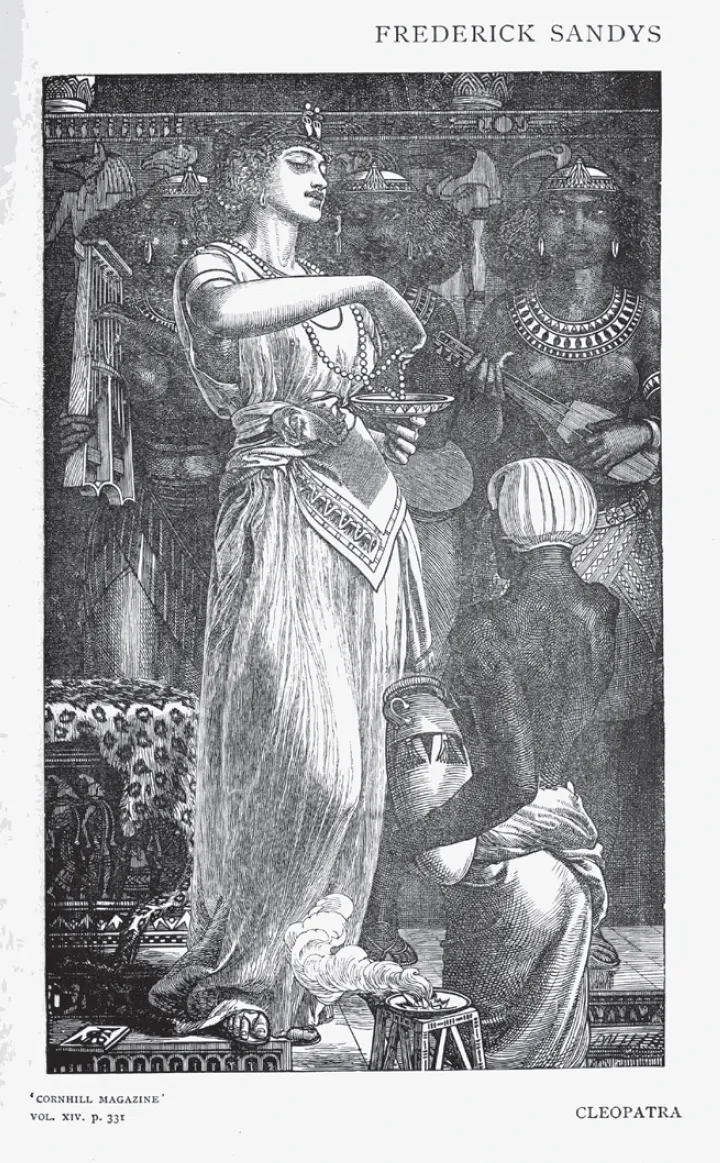

Cleopatra, as portrayed by Frederick Sandys in Cornhill Magazine, Vol xiv, 19th century

When Caesar and his Roman army arrived in Egypt, Cleopatra’s brother had already had Caesar’s rival for the throne, Pompey, murdered, which hadn’t pleased Caesar as much as expected. Cleopatra realised that she was more likely to charm him than defeat him and had herself ‘delivered’ to him rolled up in bedding – pleasing him with her initiative, but upsetting Ptolemy who saw her secretive arrival as a betrayal. He was to drown when attempting withdrawal from the Romans, with other Egyptians, following a battle on the banks of the Nile.

While not as beautiful as Elizabeth Taylor, Cleopatra certainly had the personality, sensuality and ‘sweetness’ to successfully woo such a womaniser as Caesar, a man in his fifties, and their affair resulted in a pregnancy, keeping Caesar in Egypt for much longer than planned.

Legally and traditionally, Cleopatra was now Queen and had married Ptolemy in keeping with Egyptian custom. But Caesar had to take up his neglected duties, leaving three Roman legions behind to protect her. When Cleopatra arrived in Rome to join him in 45 BC, accompanied by her ‘husband’ and young son, the splendour of her arrival amazed even the wealthy Romans. The Romans, however, and perhaps hypocritically, were not fond of this foreigner, this public flaunting of Caesar’s mistress. In the meantime, her brother-husband vanished … very conveniently.

Cleopatra was left with no protection once Caesar was assassinated in 44 BC and she returned to rule Egypt with her son Ptolemy XVI, the last of his dynasty. Another, younger, Roman, Mark Antony, requested a meeting in Ephesus – in what is now Turkey – and was treated to another of Cleopatra’s magnificent arrivals, on a suitably bedecked barge. He too became enamoured with the manipulative queen, even though she persuaded him to have her sister, a threat to her power, assassinated. He could refuse her nothing it seems. The duo produced three children, and, when his wife died, his idea of marrying his rival Octavian’s half-sister (Octavia) was not part of Cleopatra’s plan. The political union went ahead, the compromise being that Mark Antony could become her husband under Egyptian law, though not her king, the title kept for Caesar’s son, her eldest, Caesarion. Mark Antony later renounced his marriage to Octavia, insulting Rome.

Octavian, Caesar’s legal heir, and now Mark Antony’s arch enemy, defeated him and his forces on land and sea, prompting his suicide. A devastated Cleopatra was put under house arrest by Octavian who was not influenced by Cleopatra’s wiles. Her theatrical suicide, the result of the bite from an asp hidden, supposedly, under figs brought in by her servant, is substantiated by various sources; but they also collectively agree that such a bite, alone, would not have produced the pain-free death attributed to her, that poison was the main cause of death.

Her death is not the only mystery, of course. Whether she had her king-brother-husband killed in the way she had her sister killed … plenty of historians and writers have tried, and failed, to find a definitive answer.

DIGBY, Jane 1807–81

The daughter of an Admiral and a Viscountess, educated, and beautiful too, Jane mixed in the right circles and was swept off her feet when just seventeen by a Baron twice her age. Three years after their marriage, his taking a mistress may have prompted Jane to start her own string of affairs, starting with a lowly librarian from near her family’s home in Holkham, Norfolk and progressing to her cousin Colonel Anson, who was probably the father of her son, Arthur (1828–1830).

When he tired of her, she switched her attentions to the besotted Prince Felix Schwarzenberg, the Austrian attaché, who was living in Harley Street. The affair was not handled discreetly, and, again, Jane became pregnant but this time the relationship was stronger and she followed the Prince to Switzerland, where he had been sent when the affair surfaced. Her husband finally started divorce proceedings, the case causing a media sensation at a time when divorce was so rare that it needed an Act of Parliament before it went ahead; and a time when most women were happy to be stay-at-home wives, keeping any affairs behind firmly closed doors. She received a generous settlement and gave birth to the Prince’s daughter in Basle, only to find that his Catholicism and career plans prevented him from marrying her.

It was Jane who was now besotted and she followed Felix to Germany, where King Ludwig of Bavaria noticed her and may have become her next lover. In the meantime, the German Baron Karl von Venningen pursued her and even assumed paternity of her next child in 1833, whether his or not. She agreed to marry Karl in spite of the feelings she still had for Felix and her lack of feeling for Karl, becoming a mother again, but this time accepted at court and high society. That was until she fell for a hell-raising Greek count, Spiridion Theotoky, (the antithesis of her husband) who apparently fought Karl in a duel, this seemingly the trigger that finally ended her marriage.

Jane converted to Greek orthodox and married her count five years later, giving birth to a son. The marriage in 1841 was again damaged by her husband’s infidelity, leading promptly to her own adultery with none other than King Otto of Greece, but the couple stayed together until their son died, aged six, falling from a balcony. This drove Jane away and she now devoted herself, for a while, to travel, becoming the mistress of an Albanian general living in the mountains with a brigand army; until he slept with her French maid. This was the infi...