![]()

Chapter 1

My Camera and the Kaiser

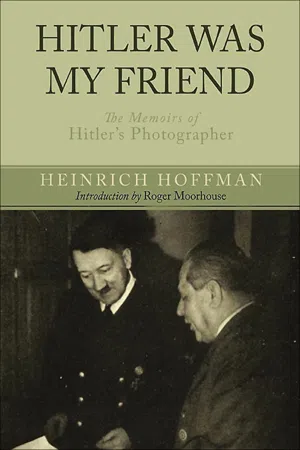

‘HITLER’S PHOTOGRAPHER’. Those two words will probably suffice to recall me to the minds of those who are sufficiently interested to ask themselves – who is this Heinrich Hoffmann?

By profession I have always been a photographer, and by inclination a passionate devotee of the arts, a publisher of art journals and a devout, if modest, wielder of pencil and brush. I served my professional apprenticeship in the well-established studio of my father, and in my turn became a master-craftsman in my art. In the course of years, kings and princes, great artists, singers, writers, politicians and men and women famous in all walks of life paused before my camera for those few seconds that were all I required to perpetuate the person and the occasion.

It was purely in the course of those professional activities that I first came into contact with Adolf Hitler – a chance assignment from which sprang a deep and lasting friendship, a friendship that had nothing to do with politics, of which I knew little and cared less, or with self-interest, for at the time I was by far the more solidly established of the two of us; but one that flashed into being at the contact of two impulsive natures, and was based partly on a mutual devotion to art and partly, perhaps, on the attraction of opposites – the austere, teetotal, non-smoking Hitler on the one hand, and the happy-go-lucky, bohemian bon viveur, Heinrich Hoffmann on the other.

But equally it was a friendship that kept me, throughout the most violent, turbulent and chaotic years in the history of the world, closely at the side of the man who was the central figure in them. With Hitler, the Führer and Chancellor of the Third Reich, I have but little concern; but Adolf Hitler, the man, was my friend, from the time of his earliest beginnings to the day of his death. He returned my friendship and gave me his complete confidence; he looms large in the tale of my life.

It was in 1897 that I entered the family business as an apprentice. Over the studio shared in common by my father and my uncle in the Jesuitenplatz in Regensburg hung proudly a pompous shield, bearing the proud inscription –

HEINRICH HOFFMANN, COURT PHOTOGRAPHER

His Majesty, the King of Bavaria

His Royal Highness, the Grand Duke of Hesse

His Royal Highness, Duke Thomas of Genoa,

Prince of Savoy

This shield had been a fairly costly investment, for in order to obtain permission to use the title, one had had to make a pretty solid payment to the Court Marshal’s Office. But my father and uncle lost no opportunity of pointing out with pride that they had not bought, but had earned the titles; and indeed they had photographed many of the members of the Wittelsbach royal family, as well as the Grand Duke von Hessen und bei Rhein, the Duke of Genoa and many other princes. In recognition of their meritorious performances in the art of photography they had been presented by the Prince Regent, Luitpold of Bavaria, with a handsome gold tie-pin, with a large L in brilliants, as a mark of his particular appreciation, and every Sunday there was always a voluble argument between the two partners as to whose turn it was to wear the royal pin!

When I started work, my most urgent task was to look after the head- and arm-rests that, in those days of long exposures, were used as supports for our illustrious clients and to guard them against the dangers of a stiff neck. In addition it was my duty to dust all those other props that were thought essential in every self-respecting studio. There was, for instance, a boat with all its sails set – a giant broken egg, into which naked babies were popped, giving the impression that the new citizen of the world had not been delivered by stork, but had been well and truly hatched, and many other monstrosities.

Our studio itself was designed in the Makart style, after the house of the once famous Viennese painter, Hans Makart, whose imposing picture, The Entry of Charles V into Antwerp, brought him such fame. When this picture was first exhibited in Vienna it aroused the greatest possible excitement. Indeed, among its naked hetairae many a husband of Viennese society thought he recognised his wife, who had obviously posed for the artist and had been faithfully and completely perpetuated for all time; and a crop of suicides and divorces had been the result.

In those days I simply loathed Makart, because the copies of his bouquets, which hung in profusion on our walls, his gilded vases stuccoed with rice and his picture frames were one and all quite exceptional as receptacles for dust.

One Sunday afternoon, just as I was about to close the studio, a man came in.

‘I want my photo taken!’ he declared abruptly.

With suitable expressions of regret I told him that there was no one available who could fulfil his wish.

‘Well – you’re here! You take me!’

I declined. ‘I’m sorry,’ I said, ‘but I’m afraid I’m not competent.’ The man, however, was not to be denied and assumed a threatening attitude; and so I took my decision, trembling and protesting all the time that I could not guarantee a good picture. Taking not the slightest notice of me, the man went into the dressing room and from his suitcase took out a new suit of clothes.

Having packed his discarded clothes into the suitcase, he assumed his pose. I disappeared beneath the black cloth, focused the camera and with a thumping heart stammered the conventional, ‘Now – smile and look pleasant, please!’

The man stood as expressionless as a memorial statue. When the sitting was over, my forceful client departed, leaving his suitcase behind him and saying that he’d pick it up later, when he called for the photographs. The photograph turned out to be a very good one. With pride I showed it to my father and uncle. But the client never returned, either to collect his photograph or to retrieve his belongings.

Weeks later, we opened the suitcase and found that, in addition to the old suit, it contained a purse full of gold coins and an air gun. The police established the fact that the money and the suitcase had belonged to a peasant woman who had been found murdered in the vicinity of Regensburg. Later it was further established that the murderer had enticed his victim to come out of her cottage by imitating the cries of agitated hens! But of more interest to the police than this find was the photograph I had taken. It appeared on the ‘WANTED’ notice boards of all police stations, and so my first photograph was a great sensation.

My apprenticeship ended in 1900, but I was to have remained in the family business until I attained my majority. I myself, however, was anxious to be off; and so at the age of sixteen, I found myself working for Hugo Thiele, Court Photographer to the Grand Duke von Hessen, in Darmstadt, and to me it was most interesting to be allowed to help with the photographing of members of the Grand Ducal family, who frequently patronised my employer.

About this time the Artists’ Colony founded by the Grand Duke was opened on the Mathildenhöhe. This exhibition, which opened up new vistas in both architecture and art, was a great success and had a marked effect throughout Germany, not only on art, but also on photography. It was from Darmstadt that the revolutionary movement started to get rid of the old baronial hall drop-curtain, the palms, the battlements and all the other monstrosities and fustian that cluttered up the photographer’s studio, and instead, with natural lighting and in natural surroundings, to give an entirely new look to photographic portraiture. Weimer, another leading photographer of Darmstadt, was the first to cast aside all these old impedimenta and to strive to replace the artificiality of the posed portrait with an easy, natural picture. Whenever he could, he always preferred to photograph his clients in their own homes, surrounded by their own belongings, at ease in an atmosphere that was familiar to them, rather than have them come to his studio.

When, as often happened, we were commanded to the Grand Ducal Palace to take photographs, there was always great excitement. The Grand Ducal court, thanks to the close family ties that bound it to all the most powerful princely houses of Europe, enjoyed at that time an importance out of all proportion to the size of the State. Of the three sisters of the reigning duke, Ernst Ludwig, all of whom I saw when they were being photographed during various visits to their brother, one had married Prince Henry of Prussia, the second had married into the Russian Royal Family, while the third, Princess Victoria Elizabeth, had become the wife of Prince Louis of Battenberg, who later became the Marquess of Milford Haven.

I was at the time profoundly impressed by the air of tragic melancholy that hovered over the great ladies from Russia, like an omen of the terrible fate that was later to destroy them. The Tsarina was always shy and aloof in the presence of strangers, and she always seemed to be relieved when the business of taking photographs was completed. Her much more beautiful sister, the Princess Sergei, was more gracious and natural. I heard later that after her husband had been murdered, she visited the murderer in his Moscow cell and with truly divine patience tried to find out the motive for the crime; and that finally, like a true angel of mercy, she had forgiven him.

It was axiomatic that our illustrious clients should not be incommoded in any way, and we did our utmost to speed up the process as much as possible. Any delay in placing the camera in position, any long drawn-out correction of the pose called forth a sharp reprimand and an urge to swifter dexterity. The Grand Ducal family tired easily and was inclined to be impatient.

A dark room had been fitted up in the Palace, and plates were developed as soon as they had been exposed. In this way, in the event of any failure, the photo could swiftly be taken again. The developing was part of my duties, and on one occasion during a visit of the Princess Sergei, I was hastening into the darkroom, when a gentleman who was unknown to me asked if he might come with me, as he was very interested in the process of developing.

Cordially I invited him to accompany me. While at work, I asked him whether he thought it would be possible for me to catch a glimpse of the Grand Duke? My interest, I explained, was heightened by the fact that our family studio bore the proud title ‘Heinrich Hoffmann, Court Photographer to the Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig von Hessen und bei Rhein’, but that, although I had been in the Palace often enough, I had so far never seen him.

‘Furthermore,’ I continued, ‘I am really one of the Grand Duke’s subjects, for my father was born in Darmstadt and served in the White Dragoons.’

‘I think it might be arranged,’ smiled my visitor, and as we left the darkroom together he thanked me and pressed a handsome tip into my hand. I was intrigued, and I asked a servant who the gentleman was.

It was none other than the Grand Duke himself, and he had presented me with a thaler with his portrait on it!

I was anxious to obtain practical experience in as many branches of photographic art as possible, and so, in 1901 I thought the time had come to move on, and I went to Hei...