![]()

Campaign Chronicle

6 February–9 May 1588: Medina Sidonia Takes Command

The Duke of Medina Sidonia’s immediate reaction to being appointed as Santa Cruz’s replacement seemed to border on panic. He wrote to King Philip, emphasising his unsuitability for the job: ‘I have not health for the sea, for I know by the small experiences I have had afloat that I soon become sea-sick… Besides this, your Excellency knows, as I have often told you verbally and in writing, that I am in great need, so much so that when I have had to go to Madrid I have been obliged to borrow money for my journey… Apart from this, neither my conscience nor my duty will allow me to take this service upon me. The force is so great, and the undertaking so important, that it would not be right for a person like myself, possessing no experience of seafaring or of war, to take charge of it.’

Opinions differ as to Medina’s Sidonia’s real motives in making this protest, which, as he possibly expected, was ignored. It was quite customary for the captain-general of a Spanish fleet to be a man whose social standing considerably outweighed his experience of the sea. He would be expected to rely on professional advisers for assistance in that respect. The duke’s real reasons may have been that, as result of his close involvement with the preparations already made, he was aware of the doubts about the expedition’s prospects held by experienced commanders like Santa Cruz and Recalde, and was making his protest as a personal insurance against repercussions in the event of the failure he regarded as highly likely.

However, the initial task awaiting Medina Sidonia when he arrived at Lisbon was one suiting his proven abilities as an administrator. During the following weeks he worked hard to overcome the problems inherited from Santa Cruz with a fair degree of success. Guns, together with powder and shot, were redistributed more equally among the ships of the fleet, and stores – the quality of which, no one dared investigate too closely – loaded aboard the ships. The duke seems to have worked amicably with his squadron commanders, and issued detailed instructions regarding rations for his crews, covering what he must have felt to be every conceivable aspect, down to the order in which different wines were to be issued.

A typical sea-battle of the period.

By early May, the Armada seemed as ready for sea as it was ever likely to be. Morale among many crews was high, with the men motivated by a mixture of the religious fervour emphasised in Medina Sidonia’s final orders, and by the more mundane – if understandable – thoughts of the booty they would gather in a vanquished England. An unknown Spanish soldier aboard the Armada wrote to his wife:

‘Your grace will say that she should commend me to God, for if there is one thing for which I wish to go on living, it is to return to her and to provide for her as by rights I ought, and if God gives me life, when this expedition to England is over, which will be very soon, I shall go back to my house again with whatever God shall be pleased to give me in order to have some peace. For it was for this that I came on this expedition, not because I am any lover of wandering away from home and God knows that all I want is to be there again in peace and with some little rest.’

On 9 May, after a colourful and impressive service of dedication in Lisbon Cathedral, Medina gave the order to weigh anchor and put to sea. His instructions to the men of the Armada were as follows:

‘First and foremost, you must all know, from the highest to the lowest, that the principal reason which has moved His Majesty to undertake this enterprise is his desire to serve God, and to convert to his church many peoples and souls who are now oppressed by the heretical enemies of our Catholic faith.

‘I also enjoin you to take particular care that no soldier, sailor or other person in the Armada shall blaspheme, or deny Our Lord, our Lady or the Saints, under very severe punishment inflicted at our discretion. With regard to other less serious oaths, the officers of the ships will do their best to repress their use, and will punish offenders by docking their wine ration; or in some other way at their discretion. As these disorders usually arise from gambling, you will endeavour to repress this as much as possible, especially the prohibited games, and allow no play at night on any account.

‘As it is an evident inconvenience, as well as an offence to God, that public or other women should be permitted to accompany such an armada, I order that none should be taken on-board. If any attempt be made to embark women, I authorise the captains, and masters of ships to prevent it, and if it be done surreptitiously the offenders must be severely punished.

‘Every morning at daybreak the ships’ boys shall, as usual, say their “Salve”, at the foot of the mainmast, and at sunset the “Ave Maria”. Some days, and at least every Saturday, they shall say the “Salve” with the Litany.

‘The ships will come to the flagship every evening to learn the watchword and receive orders… the flagship must be saluted by bugles if there are any on-board, or by fifes, and two cheers from the crews. When the response has been given the salute must be repeated. If the hour be late, the watchword must be requested, and when it has been obtained another salute must be given, and the ships will then make way for others.

‘In case the weather should make it impossible to obtain the watchword on any days, the following words must be employed:

Sunday: Jesus

Monday: Holy Ghost

Tuesday: Most Holy Trinity

Wednesday: Santiago

Thursday: The Angels

Friday: All Saints

Saturday: Our Lady

‘It is of great importance that the Armada should be kept well together, and the generals and chiefs of squadrons must endeavour to sail in as close order as possible… Great care and vigilance must be exercised to keep the squadron of hulks always in the midst of the fleet. The order about not preceding the flagship must be strictly obeyed, especially at night.

‘No ship belonging to, or accompanying, the Armada shall separate from it without my permission. If any should be forced out of the course by tempest, before arriving off Cape Finisterre, they will make direct for that point, where they will find orders from me; but if no such orders be awaiting them, they will then make for Corunna, where they will receive orders. Any infraction of this order shall be punished by death and forfeiture.

‘On leaving Cape Finisterre the course will be to the Scilly Isles, and ships must try to sight the islands from the south, taking great care to look to their soundings. If on the voyage any ships should get separated, they are not to return to Spain on any account, the punishment for disobedience being forfeiture and death with disgrace…’

10 May–19 June: From Lisbon to Corunna

The Armada, with its brightly-painted ships’ hulls, glowing banners, and sounding trumpets, made a brave show as it left Lisbon harbour: but frustration quickly followed. For the next two weeks, held back by contrary winds, the fleet was unable to leave the mouth of the Tagus. On 14 May, Medina Sidonia wrote reassuringly to the king: ‘the Armada took advantage of a light easterly wind, which blew for a few hours on the 11th instant, to drop down the river to Belem and Santa Catalina, where the ships now only await a fair wind to sail. God send it soon!’ Ominously, just before sailing, Medina Sidonia had received a message from the Duke of Parma, written in March, from which it was apparent that Parma had fewer troops available than Medina Sidonia had expected – only about 17,000 – and that much of his invasion fleet was unready.

Medina Sidonia’s worries mounted with every day the Armada remained wind-bound in the Tagus. The almost 30,000 men aboard his ships not only made serious inroads into the provisions intended for the voyage, but crammed together as they were in unsanitary conditions, disease spread rapidly and morale fell.

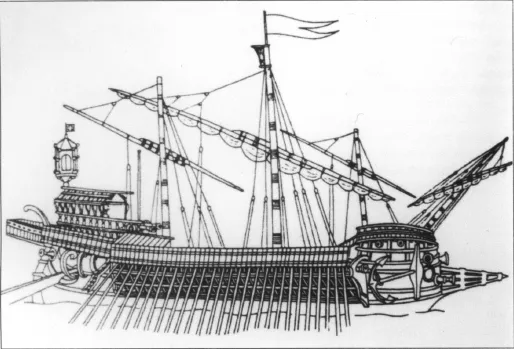

A Galleass. Note the high stern castle and the battery of guns mounted at the prow. An ornate stern lantern, similar to that seen here, was reportedly shot off a galleass during the engagement off the Isle of Wight.

Elizabethan ships, including a ‘race-built’ galleon.

At last, on 30 May, the winds turned favourable, allowing the Armada to begin moving out into the open sea. It was dawn next day before the last ship was clear, and soon afterwards the fleet ran into contrary freshening winds, followed by stormy weather, which forced the Armada to beat up and down, in the process losing most of the ground already gained. On 10 June, when the winds at last came into the NW direction favourable for the Spaniards, the fleet lay at latitude 40 degrees north – further from Cape Finisterre than when it had left Lisbon. On the same day Medina Sidonia wrote to Parma outlining his strategy for the coming campaign. The duke explained that he had been instructed to avoid battle, if possible, and make directly for a rendezvous with Parma: ‘I very much wish the coast [of Flanders] were capable of sheltering so great a fleet as this, so that we might take a safe port to have at our backs, but as this is impossible, we shall have to make the best use we can of what accommodation there may be, and it will be necessary that as soon as Captain Moresin arrives with you (which will depend on the weather), you should come out to meet me…’

Parma was dismayed at the implications of Medina Sidonia’s letter, and twelve days later wrote to the king that the captain-general of the Armada ‘seems to have persuaded himself that I may be able to go out and meet him with my boats. These things cannot be.’ Parma’s flat-bottomed barges were barely fit for the short crossing of the English Channel in the Dover Straits, and were certainly incapable of making a longer voyage: ‘This was one of the principal reasons which moved Your Majesty to lay down the precise and prudent orders you did, that your Spanish fleet should assure us the passage across, as it is perfectly clear that these boats could not contend against ships, much less stand the sea, for they will not weather the slightest storm.’

There is no record that Medina Sidonia ever learned of Parma’s vitally important but discouraging letter. In any case, the Armada was now facing its own problems. By 17 June the fleet, sailing at an average speed of 4 knots, at last sighted Cape Finisterre at the north-west tip of Spain, but by now Medina Sidonia had discovered that a large proportion of the stores embarked at Lisbon were rotten and the water foul, with the result that dysentery had begun to spread among the crews. The duke was forced to admit to the king that the supplies ‘have gone bad, rotted and spoiled… We have had to throw a large part of the food overboard because it was only giving men the plague and making them sick… So I must inform Your Majesty and humbly beg you to agree to send out to us more provisions to supplement what we have. What we mainly lack is meat and fish, but we need everything else as well.’

Then, as the Armada waited off Finisterre for the expected supply ships, further misfortune struck. Gales blew up, scattering the fleet over a wide area, some vessels being driven as far north as the Scilly Isles. With most of his fleet missing, Medina Sidonia was forced into the port of Corunna to wait for the stragglers to rejoin him.

Ensign Esquivel recounts the ordeal of his pinnace (a small vessel, propelled by oars or sails) in the storm:

‘On Friday, 2 July, at daybreak we sighted St Michael’s Bay [Mounts Bay, Cornwall] and Cape Longnose [the Lizard] 5 or 6 leagues distant. The general opinion was that, being so near the land, we should hardly fail to catch a fisherboat during the night. The wind then rose in the SW, with heavy squalls of rain, and such a violent gale that during the night we had winds from every quarter of the compass. We did our best by constant tacking to keep off the land, and at daybreak the wind settled in the N., and we tried to keep towards Ireland in order to fulfil our intention, but the wind was too strong, and the sea so heavy that the pinnace shipped a quantity of water at every wave. We ran thus in a southerly direction, with the wind astern blowing a gale, so that we could only carry our foresail very low. At four o’clock in the afternoon, after we had already received several heavy seas, a wave passed clean over us, and nearly swamped the pinnace. We were flush with the water, and almost lost, but by great effort of all hands the water was baled out, and everything thrown overboard. We had previously thrown over a pipe of wine and two butts of water. We lowered the mainmast on to the deck, and so we lived through the night under a closely reefed foresail.

‘On Sunday we were running under the foresail only, and at nine o’clock in the morning we sighted six sails, three to the N., and three to the SE, although they appeared to be all of one company. We ran between them with our foresail set, and two of those on the SE gave us chase. We then hoisted our mainmast and clapped on sail, and after they had followed us until two o’clock, they took in sail and resumed their course. At nine o’clock we sighted another ship lying to and repairing, with only her lower sails set.

‘On Monday, 4 July, we sighted land off Rivadeo [Northern Spain].’

20 June–23 July: Final Preparations

Various storm-blown stragglers from the Armada were sighted off the Scillies, and their presence gave Elizabeth and her commanders final proof, if such were needed, that the Spanish onslaught was imminent. Since early in the year, despite continued procrastination by the queen herself, the tempo of English preparations had been increasing. Drake, in command of the Western Squadron at Plymouth, constantly urged that the English fleet should launch a pre-emptive attack on Spanish ports.

While some of her privy council agreed with Drake, the queen herself remained reluctant to act. Sir Francis was still pressing his case early in June when the lord admiral, Charles Howard, arrived at Plymouth to assume overall command. Howard officially hoisted his standard on 2 June. Drake’s reaction at being superseded by a courtier commander – though from a family with a long-standing naval background – is not recorded, but relations between the two were apparently initially cordial, with Howard praising the state of preparedness of Drake’s squadron, and Sir Francis quickly convincing the lord admiral of the case for his offensive strategy. A few days after his arrival, Howard wrote to Lord Burghley of the privy council that he intended to sail for the coast of Spain as soon as possible: ‘with intention to lie on and off betwixt England and that coast to watch the coming of the Spanish forces.’ He had, however, guarded against any attempt by Parma to slip across the Channel by leaving Lord Henry Seymour with a forty-strong squadron to guard the Straits of Dover. Indeed, the lord admiral probably over-insured in this respect by giving Seymour at least two of the newest of the Queen’s Ships, Vanguard and Rainbow, which would have been of more use engaged against the Armada from the start of the campaign.

An Elizabethan seaman. The dress of seamen in both fleets was probably similar.

Howard’s main worry was, and would remain, supplies. He found the Plymouth ships to be woefully under-provisioned. On 7 June, possibly indirectly criticising Drake, he told Burghley: ‘I perceive that the ships and also the victuals be nothing in that readiness that I looked they should be in… We have here now about eighteen days’ victuals and there is none to be gotten in all this county.’ However, Howard had nothing but praise for his officers and men: ‘There is here the gallantest company of captains, soldiers and mariners that I think ever was seen in England. It were a pity they should lack meat when they are so desirous to spend their lives in Her Majesty’s service.’

The ...