![]()

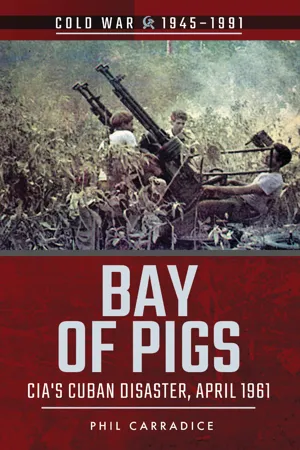

1. PERSPECTIVE

‘How may I live without my name? I have given you my soul; leave me my name.’

Arthur Miller, The Crucible

There are moments in history which, by virtue of the way in which we describe, log or name them, are instantly memorable. Sadly, the names we use to label the events are all too often more interesting than the actual occasions themselves.

The Defenestration of Prague is one. Over the years defenestration became something of a tradition in Prague, citizens showing their displeasure or opposition by hurling their political rulers out of the windows of the local castle. If the victims were lucky they would land on a dung heap or something soft. If not, like Jan Masaryk in 1948, ‘C’est la guerre.’

The War of Jenkins Ear sounds wonderful but in reality was little more than a series of skirmishes between trading vessels from Britain and Spain. The war began in 1739 when Captain Robert Jenkins had his ear cut off in a shipboard scuffle – and no, the severed ear was not presented to Parliament as popular sentiment would have us believe.

Despite its fascinating nomenclature, the Diet of Worms was nothing more than an assembly of the Holy Román Empire held in the Germanic city of Worms in 1521. Admittedly, Martin Luther was there to defend his position but nailing his Ninety-five Theses to the door of the Castle Church, Wittenberg was probably a lot more interesting. How did he do it, one nail in the corner or ninety-five separate pins?

The list is interminable. However, one of the few events that sounds fascinating when you first hear of it, yet still manages to live up to its potential is the sad and ultimately tragic fiasco of the Bay of Pigs Invasion.

A precursor to the Cuban Missile Crisis, it took place in 1961 and was an inept, entertaining and sometimes farcical attempt by the CIA to covertly design and implement an invasion of Cuba. The invasion would, it was hoped, spark a rising that would lead to the downfall of Cuban leader Fidel Castro.

Still renowned and commemorated in Cuba, the participants and events have faded from the memory of the general public in America and Britain. It is hardly surprising with popular opinion focusing on Kennedy’s supposed victory in the Cuban Missile Crisis the following year. The Bay of Pigs was a defeat, a spectacular defeat, a failure of mammoth proportions. Best consign it to those realms of glitches and failures that only surface in the midnight hours.

Playa Larga, Red Beach as it was called, the northernmost landing beach.

The Bay of Pigs was the USA’s worst military disaster since the war of 1812 when British forces burned the White House. And, of course, there was more to come in the shape of the wrong war at the wrong time: the conflict in Vietnam. Yet the ramifications from the shambolic 1961 attempt to invade Cuba were equally as far-reaching.

If events at the Bay of Pigs have more in common with an episode of Monty Python’s Flying Circus than they do with the 1945 invasion of Iwo Jima and the landing at Inchon during the war in Korea – both of which it was supposed to replicate – then that simply adds to the intrigue.

More importantly, it adds to the gung-ho foolishness of America’s Central Intelligence Agency and the Joint Chiefs of Staff who were meant to oversee the plan and approve both its development and implementation.

The whole sorry episode was part of America’s post-war paranoia about communism. At a time when self-aggrandisement and self-congratulation were part of the American people’s belief in themselves as ‘the policemen of the world’, the spectre of creeping communism would not lie down and die.

Above all the débâcle revolved around the desire of America’s leaders to maintain what was called ‘plausible deniability’. Although funded by the US Treasury with soldiers trained and equipped by the CIA and the US military, the plan was presented to the world as an invasion cobbled together and led by Cuban exiles who had fled the island after Castro’s revolution. These exiles, according to the deception, were now attempting to win back control of their homeland.

In reality, no one had to delve too deeply into the murky depths of the operation to realize that the dark hand of the CIA was immersed in the plan, right up to the armpits. To mix yet another metaphor into the catalogue of disasters, when the dust had cleared the CIA and, by default, the Kennedy administration as well, had received a very bloody nose.

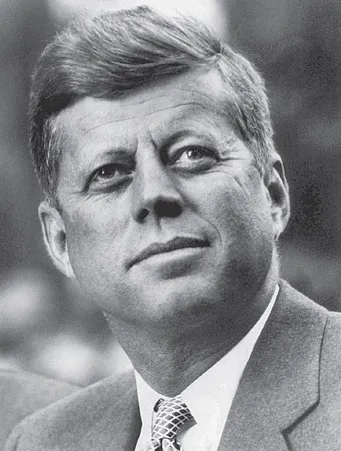

The Bay of Pigs affair saw John F. Kennedy at his worst: lacking in judgement, naïve and ineffective. And while events may have occasionally descended into the hilarious humour of a Whitehall farce there is also a tragic side to the invasion. The landing on 17 April 1961, the military build-up in the weeks before and the dramatic days that followed have the tragi-comedy appeal that Shakespeare would have loved.

Over a hundred members of the invading exile army were killed before they could even get off the landing beaches or cross the wild Zapata swamp-lands. Many more, specially trained guerrilla fighters who had been sent ahead of the invasion to act as infiltrators, and locals who were regarded simply as potential collaborators, were rounded up and either shot or imprisoned by Castro’s forces.

President John F Kennedy, young, dynamic – naïve and inexperienced.

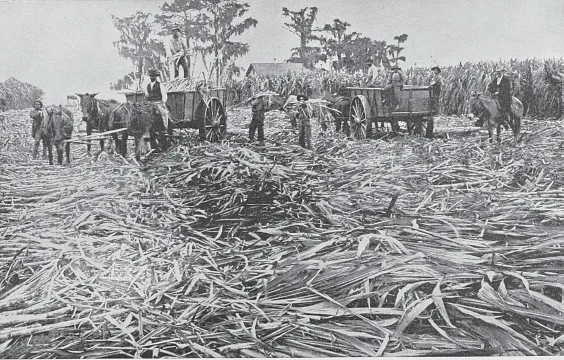

Castro’s militia, 200,000 part-time soldiers whose real occupations were jobs like teaching, cane cutting or charcoal burning, bore the brunt of the fighting around the killing grounds of Playa Girón and Playa Larga in the early hours of the first day. Attempting to support the regular Cuban Army, they took high casualties, possibly in the thousands. The figure has never been made totally clear.

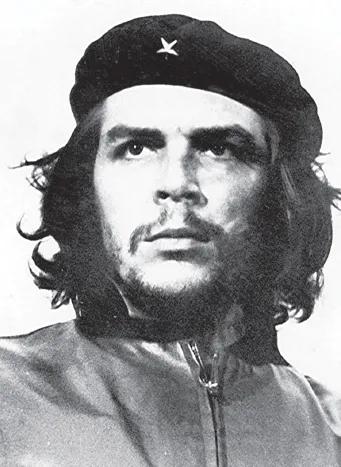

However, the extensive casualty list acted, not as a deterrent for Castro’s revolutionaries, but as a brilliant recruiting tool. He could not have planned it better. As an ironic Che Guevara wrote in a scribbled note to President Kennedy: ‘Thanks for Playa Girón. Before the invasion, the revolution was weak. Now it is stronger than ever.’

If the Bay of Pigs was a ‘coming of age’ for Fidel, for Che and for the new regime, it was also a very definite wake-up call for the US. The disaster was a lesson learned even if it was one that Kennedy and his advisors would not have deliberately chosen: ‘It was a horribly expensive lesson, but it was well learned. In later months the President’s father would tell him that, in its perverse way, the Bay of Pigs was not a misfortune but a benefit.’

It is hard to see, fully, Joe Kennedy’s logic and it is doubtful if JFK himself ever quite grasped what his father was trying to say. JFK could never get beyond the human cost. Joe, nothing if not a first-class pragmatist, was not concerned about people. Ideas and causes were his area of interest.

John F. Kennedy had inherited the operation from his predecessor, Dwight Eisenhower. The old victor of the Normandy landings was more than happy to leave the final decision on whether to launch or postpone the Perspective invasion to his successor. According to Jack B. Pfeiffer: ‘Following his initial interest in the developing program, President Eisenhower’s personal involvement [had] dropped off sharply by the late summer of 1960.’

Che Guevara, revolutionary icon.

Perhaps realizing that Cuba was something of a poisoned chalice, Ike was certainly more interested in things like golf during the final days of his presidency. It might be an urban myth but for many years popular opinion held that the floor of the Oval Office behind the President’s desk was pitted and indented by the spikes on Eisenhower’s golf shoes where he had rushed in for a meeting after practising his shots on the White House lawn.

And while Kennedy might later lament that none of his advisors had attempted to stop him making foolish decisions, he learned from his mistakes. Perhaps that was what his father had been trying to tell him.

For some time after the failure JFK was depressed and unhappy. His wife Jackie and brother Bobby had never seen him so low. Always susceptible to bouts of poor health, there were serious concerns about what the stresses and strains of the presidency were doing to him. Time, however, was a good healer. A few weeks later, in a conversation with friend and journalist Ben Bradlee, JFK’s humour and fighting spirit rose to the surface again. Like many of his supposedly off-the-cuff remarks, Kennedy’s words to Bradlee were carefully thought out, laced with heavy irony and intended to make a point, as quoted by Dalleck: ‘The first advice I’m going to give to my successor is to watch the generals and to avoid feeling that because they were military men their opinions on military matters were worth a damn!’

Joe Kennedy Snr, the dominating, and domineering, force behind the Kennedy family.

It was a stance that did not change throughout his remaining two years as president and was a significant factor in the way he handled the coming Cuban Missile Crisis.

Tragic, farcical, foolish, heroic – the fiasco at the Bay of Pigs was all of those things. Even the name, the Bay of Pigs – Cochinos Bay as the Cubans call it – has an element of farce about it, an element of farce that belies the tragedy of the whole affair.

Now, with hindsight, it seems almost inconceivable that such a plan could be devised and implemented. And, of course, it was the ordinary soldiers and patriots who suffered the most.

There are participants still alive – from both sides – men and women who might view the events of April 1961 with different perspectives but all of whom know that they took part in a dynamic and world-changing piece of history.

Perhaps the greatest sadness in the whole affair came with the unchallengeable belief of the Cuban exiles that the USA would send in troops to help them once the beachhead had been established. Many of the Brigade members put it on record that CIA operatives had promised help. That may have been the case but it was not, and never had been, the view of the men in charge.

A Cuban sugar plantation in the nineteenth century. (Library of Congress)

The pace of life in Cuba has changed little over the ages. Here a fisherman tries his luck with a hand line. (Photo Trudy Carradice)

Kennedy, like Eisenhower before him, was adamant that no US soldiers would ever be used. In late March 1961, as quoted by Schlesinger, he told a press conference: ‘There will not be, under any conditions, an intervention in Cuba by the United States Armed Forces … The basic issue in Cuba is not one between the United States and Cuba. It is between the Cubans themselves.’

They were laudable words, carefully chosen by JFK, which undoubtedly summed up the attitudes of both the Kennedy and Eisenhower regimes. Perhaps inevitably, the Cuban exiles who were soon to risk their lives on the beaches around the Bay of Pigs chose not to believe him. That may well have been the workings of the closed minds of driven patriots but the Cuban exiles would not have arrived at that conclusion alone. There had to have been American promises made, if only by the culpable officers of the CIA.

The real tragedy of the Bay of Pigs was that no matter what happened on the invasion beaches, it was an operation doomed to fail. Grayston Lynch, one of only two Americans to go ashore with the soldiers of Brigade 2506, admirably summed it up: ‘2506 Assault Brigade fought hard to prevent this disaster but, as we were to discover later, no amount of effort on its part could have prevented it, for this invasion was doomed long before the men of the Brigade first sighted the dim outlines of Cochinos Bay.’

Three days in April, a time to live and a time to die; three days when the Cuban exiles of Brigade 2506 felt betrayed and abandoned by a global super power that had the strength and capability but not the inclination to help them in their hour of need; three days in April that should never be forgotten.

![]()

2. BACKGROUND TO DISASTER

‘A revolution without firing squads is meaningless.’

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin

Fidel Castro seized control of Cuba at the beg...