![]()

Chapter 1

The ’45 Campaign

CHRISTOPHER DUFFY

The story of the Jacobite rising of 1745–6 will probably be familiar, at least in outline. Perhaps less well known will be the connections between the processes and key decisions that explain why the culminating battle at Culloden was fought when, where and how it was.

By 1745 Britain had lived through decades of political and religious upsets, beginning in 1688 when King James II (VII of Scotland), an ardent Catholic convert, was forced from his throne by the ‘Glorious Revolution’. This usurpation existed in an international context, for the Dutch Prince William of Orange, now installed in London as King William III, was motivated primarily by a desire to gather Britain into a league against Louis XIV of France. Catholics were actually a minority among what became known as the ‘Jacobites’, who were the many men and women throughout the British Isles who concluded that the Revolution had been a ‘fix’, engineered by small groups of powerful interests, and that the laws of God and man had thereby been set aside.

William III had married James’s daughter Mary, and a semblance of Stuart continuity was preserved when Mary’s sister, Anne, succeeded as queen, reigning from 1702 to 1714. However, the biggest ‘fix’ of all had already been engineered by virtue of the Act of Settlement (1701), which determined that after the death of the childless Anne the crown must pass to the heirs of the Electress of Hanover, a granddaughter of James I of England (VI of Scotland), and so guarantee the succession of a Protestant line. Anne died in 1714, and the throne was duly inherited by Elector George of Hanover, who but for the Act of Settlement would have had only a remote claim to the succession. Continental priorities, in this case the security of the Electorate of Hanover, were the main concern of this first of the Georges, and of his son George II, who came to the throne in 1727.

Conversely, the unrest in Britain every now and then served the interests of France and Spain. The French first intervened on behalf of the Jacobites in March 1689, when they deposited James II on the coast of Ireland with a body of 4,000 French troops. The subsequent fight of the Irish Jacobites outlasted the resistance in Scotland and the departure of King James, and came to an end only when the defenders of Limerick surrendered on favourable terms on 3 October 1691.

The celebrated Jacobite rising of 1715 was in measurable terms the largest of the four (1689, 1715, 1719, 1745), embracing much of northern England and Lowland Scotland, but it lacked cohesion and leadership, and was launched at a time of general European peace, when neither France nor Spain was inclined to intervene. In 1719 the Spanish did indeed put a small force ashore in the Western Highlands, but the troops and their Scottish supporters made scarcely any progress inland before they were defeated at Glenshiel on 10 June. The Scots dispersed, and the Spaniards were left to surrender.

In the longer term the Jacobite connections with Spain and more particularly with France proved to be a source of underlying strength, as was to be revealed in 1745. Exiled Irish Jacobite shipowners, rich from the profits of trade, slaving and privateering, proved willing to put their resources at the disposal of a new Stuart leader, Prince Charles Edward Stuart, who was more single-minded and energetic than anything that his house had produced in recent generations. Something of a Stuart army in exile had come into being in the French military service in the shape of the formidable Irish Brigade and the Regiment of Royal Ecossois, while clansmen and young Highland gentlemen circulated between Scotland and France and Spain, and so helped to build up the fund of military expertise available to the Scottish Jacobites in their homeland.

In 1743 a fresh war pitted France against Britain and its Austrian, Dutch and German allies, and at a time when the new generation was coming to the fore (for a more detailed account of the War of the Austrian Succession, see Szechi, this volume). In the theatre of war in the Austrian Netherlands (corresponding roughly to present-day Belgium), the command passed to King George’s second son, William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland. He was brave and enthusiastic, but he was no match for the French under the Marshal de Saxe, and on 11 May 1745 he was defeated at Fontenoy, which inaugurated a run of reverses that opened the Channel coast as far as Ostend as a potential base for the invasion of Britain.

How well placed were the Jacobites to take advantage of their opportunities? Since 1701 their hopes had been invested in James II’s son and heir, James Francis Edward, known as ‘King James III’ to his supporters but ‘The Old Pretender’ to his enemies. Over the course of time James III lost the credibility, will and energy to lead an armed Jacobite restoration, and the lead in militant Jacobitism was taken by his son Prince Charles Edward Stuart, the Bonnie Prince Charlie of history and legend. The Prince Charles of 1745 was a world removed from the comatose Polish-Latin hermaphrodite as conveyed in caricatures like that in Peter Watkins’s celebrated 1964 film, Culloden. On the contrary, the prince was clear-headed and determined, he was flexible enough to adapt himself to the most varied people and circumstances, and he had a rare gift for raising sunken spirits. Physically he had trained himself for his role by a taxing regime of hunting and exertion, showing a self-discipline that abandoned him entirely in later years.

Expecting a French invasion of Britain early in 1744, Prince Charles hastened from Rome to join the expedition. The project was cancelled at the last moment, which caused him to lose faith in official French help, and he invested his hopes instead in his contacts among the Irish traders. On 4 June 1745 his privately-financed expedition came together when the nimble privateer Le du Teillay met the ex-British battleship Elizabeth off the coast of Brittany, and the two sailed together for Scotland, bearing artillery, muskets, broadswords, cash and 700 troops of the Irish Brigade. This was well short of the invasion force of 6,000 that had been demanded by the prince’s potential supporters in Scotland and England, and the expedition became even more of a gamble after it encountered the British warship HMS Lyon on 9 July. The Elizabeth took such a battering in the following action that she had to turn back to France with all the troops. Le du Teillay sailed on alone, landing Prince Charles first on the little isle of Eriskay in the Outer Hebrides on 23 July, and then in the afternoon of the 25th on Arisaig on one of the most secluded coasts of the western Scottish mainland.

The prince was putting his sympathizers to a very severe test when he came ashore with his tiny group of ill-assorted associates, the ‘Seven Men of Moidart’.1 Some of the clan chiefs were hostile, while the others were uneasy about the lack of French assistance, but the prince had working for him the ancient Scottish loyalties to the House of Stuart, and the resentment which many Scots felt against the political union with England in 1707. Deploying all his persuasive charm, Prince Charles made a valuable conquest in the form of Donald Cameron of Lochiel, who commanded much respect among the western clans; he also won over the old and bent John Gordon of Glenbucket, who was the first of the eastern lairds to declare himself. On 19 August the first sizeable force assembled at Glenfinnan at the head of Loch Shiel, and the Jacobites raised their standard of red and white.

On the next day the prince’s men began their eastward march, while the government’s commander in Scotland, Lieutenant General Sir John Cope, set out from Stirling for the Highlands with a scratch force of about 1,500 troops. A battle seemed to be in the making, for the rivals were converging from opposite sides on the great grey ridge of the Monadhliath Mountains, which separated the Great Glen from upper Strathspey. At this juncture Cope lost his nerve. On 27 August he abandoned his attempt to gain the high Corrieyairack Pass, and over the following days he fled north-east to Inverness, convinced that the Jacobites were at his heels.

On 28 August, a day of blazing heat, Prince Charles crossed the Corrieyairack unopposed and descended into Strathspey. He was playing for high stakes. He rightly rejected the opportunity to chase and beat Cope, for by removing himself from the scene that gentleman had left open the road to the Lowlands. On 29 August the Jacobites arrived at Dalwhinnie at the head of the new military road which led so conveniently to the south. They were at Blair Castle in Atholl on 1 September. Two days later they traversed the narrows of Killiecrankie, and on the 4th they reached Perth, where they rested and gathered strength until the 11th. They came to Dunblane on 12 September, and the next day they reached the Lowlands when they passed the upper Forth at the Fords of Frew, a step of great symbolic and practical importance.

The Jacobites were stepping out with some urgency, for they knew that Cope had come to his senses, had marched from Inverness to Aberdeen and was taking ship there in the hope of reaching Edinburgh before Prince Charles. He was now moving as fast as he could, but he was delayed by adverse winds and tides, and he did not arrive in the Firth of Forth until after dark on 16 September. By that time Prince Charles and his 1,800 or so men were already outside the city.

Edinburgh, unlike the solidly Whig Glasgow, was divided between partisans of the houses of Hanover and Stuart. The Whigs could put precious little trust in their primitive town walls, hardly any in the hastily assembled trained bands, town guards and volunteers, and none at all in the only available regular troops, namely two regiments of dragoons who now fled the neighbourhood in panic. Early on the 17th a party of Highlanders gained entry by way of the Netherbow Port, and the prince arrived to an ecstatic welcome later in the day.

On 20 September 1745 two armies were moving to contact in the country to the east of Edinburgh. They numbered about 2,400 men each. The one was under the command of Lieutenant General Sir John Cope. Having embarked at Aberdeen, he had landed his troops on the 17th and 18th at Dunbar, the nearest secure port to Edinburgh. On shore he met the two shaken regiments of dragoons that had so far failed to offer any show of resistance to the Jacobite advance. Cope had shrunk from doing battle with the Jacobites in the Highlands, but he was now determined to strike off the head of the rebellion at a single stroke.

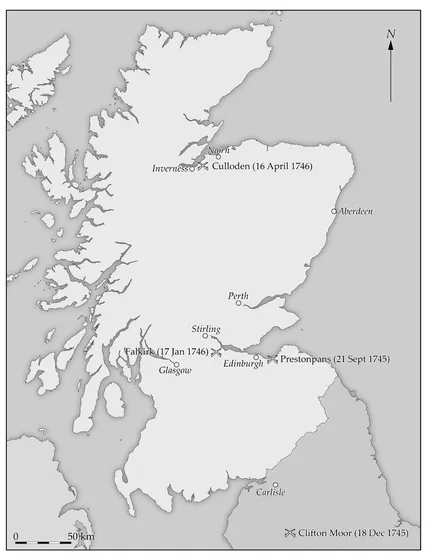

Figure 2. Location of the battles of the ’45.

On the morning of the 20th Cope learned that the other army in question, that of Prince Charles, was on the move. Cope accordingly halted his westward march on the open ground that extended from a morass north of Tranent towards the sea. He trusted that the flat and unobstructed terrain would act to the advantage of his troops, and his dragoons in particular.

Early the same morning Prince Charles and his troops set out for the east from their bivouacs at Duddingston. The Jacobites continued through Fisherrow and crossed the Esk by the spectacular ancient bridge that carried the road onto Musselburgh. Lord George Murray was in the lead with the regiment of Lochiel, and directed the march around the south of the town and Pinkie Park. Learning that Cope was at or near Prestonpans (Figure 2), he at once made for what he judged to be the key ground: the long, smooth grassy ridge of Falside Hill, rising to the south of that village. Early in the afternoon the Jacobites arrayed themselves in a north-facing line of battle along the high ground and as far as the mining village of Tranent.

Cope had his troops well in hand, and adjusted his positions repeatedly to accord with what he could discover of the enemy movements. The day ended with his original west-facing line of battle changed to one facing the marsh (the ‘Meadows’) to the south. During the night Prince Charles and his principal officers debated what to do. To attack directly across the stretch of the Meadows immediately in front of them was a physical impossibility, and so they began to think of ways of working around Cope’s position from the east. The solution was provided by Robert Anderson, the son of the owner of the Meadows, who was in the habit of going wild-fowling in the marshes, and knew of a difficult but practicable track that ran by way of Riggonhead Farm and across the far end of the Meadows.

The long Jacobite column set off just before four in the morning of 21 September 1745. The Duke of Perth made good progress with the Clan Donald regiments, which according to ancient custom made up the right wing and on this occasion had the lead. Lord George commanded the left wing, which came up behind and was accompanied by Prince Charles. In leaping one of the ditches the prince fell to his knees, and had to be hauled to his feet. In spite of this bad omen, both wings of the main force were clear of the marsh at dawn, and formed in line of battle.

Towards five the redcoats saw indistinct forms on the near side of the swamp, and in the half-light the Highlanders in their dark plaids looked like nothing so much as a line of bushes. Once he had grasped what was afoot, Cope responded with some speed. He wheeled his main force of infantry to the left by platoons, and marched them to form a 670-pace line of battle parallel to the advancing Jacobites, with the two regiments of dragoons in support. His feeble artillery consisted of four light mortars and six little ‘galloper’ cannon, and was posted on the far right. There were just two officers to serve them, and the action opened when the pair ran along the line of pieces and touched them off one by one, like pyrotechnicians at an old-fashioned firework display. After that, the dragoons opened a fire by volleys with their carbines.

As commander of the Jacobite right wing, the Duke of Perth had been concerned to leave plenty of space to allow the left under Lord George to form up on the northern side of the marsh, with the result that the duke’s wing outflanked the long line of redcoats by a useful 100 paces. This impetus gave added effect to the three regiments of Clan Donald as they advanced in good order and closed with the enemy. Men and horses began to fall among Hamilton’s regiment of dragoons (the 14th), and the sight of Lieutenant Colonel Wright being pinned beneath his horse helped to provoke a general flight which carried the reserve squadron along with it.

Cope’s centre and right were already staggering under Lord George’s attack. Cope’s artillery was overrun, and the three squadrons of supporting dragoons (Gardiner’s 13th) fled one by one. The line of redcoat infantry was now exposed, and the platoons disintegrated in succession from their right flank.

The fleeing troops crowded towards the parks of Preston and Bankton, and their panic was heightened when they lapped around the tall enclosing walls of stone. Some of the dragoons made off west towards Edinburgh, ‘with their horses all in fro’ and foam’, and a party actually galloped up the High Street and into the Castle.2 The rest of the fugitives hurried south by way of ‘Johnny Cope’s Road’ past Bankton House, and the flight continued almost without intermission all the way over the Lammermuir Hills and on to Berwick-upon-Tweed. Brigadier Thomas Fowke and Colonel Lascelles caused great scandal by arriving ahead of their men.

Between 150 and 300 of Cope’s troops had been killed, most of them mutilated in the heat of action by broadswords and Lochaber axes, and the abandoned field looked as if a hurricane had spread the contents of a slaughterhouse over the ground. The number of the redcoat prisoners was disproportionately high, at probably more than 1,300, which indicates a collapse of morale. Prince Charles forbade any gloating at the defeat of his father’s subjects, and ordered all possible care to be taken of the wounded, though nothing could be done for the gallant old Colonel Gardiner, a local man, who died of his wounds.

The appalled Whig clergyman Alexander Duncan lamented that ‘since the days of the Reformation a more dismal day did not shine on the friends of liberty and the Protestant interest in North Britain, than on the 21st of September 1745, the day of the Battle of Preston’.3 In the international context, the little battle at Prestonpans bears direct comparison with Washington’s victories at Trenton and Saratoga in 1776 and 1777, which energized the anti-British party among the colonists, shook the British and persuaded potential allies that the Revolutionary Army was a force to be reckoned with. For the Jacobites in 1745, their victory at Prestonpans enabled them to argue their case with renewed conviction among the French, who so far had been content only to observe the progress of the Highland Army, and in the next month the French pledged their formal support in the Treaty of Fontainebleau.

The first news of Prestonpans had already prompted the French to renew their plans to invade England. However, the difficulties of bringing troops and shipping together on the Channel coast repeatedly postponed the attempt until, by 26 December, the Royal Navy had been given time to redeploy its forces in the narrows. The diversionary effect was nevertheless significant, and it might have been decisive if the French had been able to co-ordinate the threat with the Jacobite advance on London. More immediately, the French began to ship support direct to Scotland by instalments. The first four vessels reached the eastern coast between 9 and 19 October, bearing small arms, artillery, ammunition and specialist military personnel.

Meanwhile the beaten redcoat army fell prey to recriminations, of officers against officers, soldiers against officers, officers against soldiers, infantry against dragoons, dragoons against infantry, and almost everybody against Cope. At the heart of the matter was the fact that an attack pressed home with cold steel had terrified everyone out of their wits. It had been an unmistakable product of the Highland military culture. In the conventional European warfare of that period, the combat of infantry against infantry had been reduced to a process of attrition, whereby the rival forces faced each other at a range of about 100yds and fired blindly into the smoke. On 21 September 1745 Cope had no reason to suppose that he was dealing with an enemy who would close the distance at a run with raised broadswords. These weapons inflicted gaping, gushing wounds that on the whole were less lethal than those made by bullets, but were endowed with a horror of their own. It was the combination of physical and mental effect that gave the Highland charge its power, and made Prestonpans the pivotal battle that it was–pivotal in the sense that it imprinted on the Highland Army a potent sense of its tactical superiority.

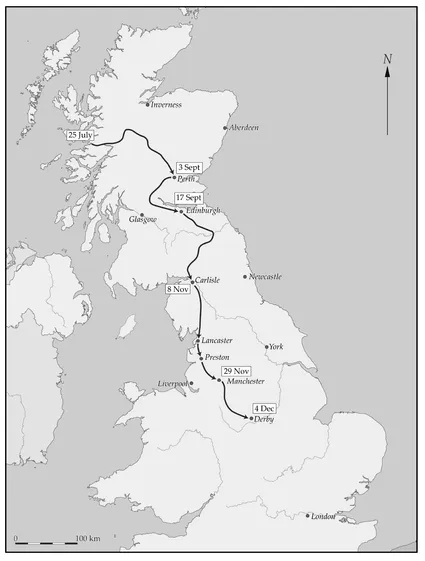

Figure 3. The Jacobite march to Derby, winter 1745.

After Prestonpans the Jacobites faced a choice. They could remain in Scotland and consolidate their grip on the country, or they could march into England along the eastern coast to Newcastle, and cut off London’s source of coal. Instead Prince Charles persuaded the Jacobite leaders into the boldest possible option, that of marching through north-west England and ultimately on London. Here lay a contradiction that the prince never managed to resolve. He was ‘going for broke’, in that his ambition was nothing less than to restore the Stuarts to the British throne, and he hesitated to spell out in detail what provisions he had in mind for Scotland. At the same time the perspective of at least some of his supporters remained not only Scottish, but locally Scottish at that, and their blinkered vision was to work to the disadvantage of the cause as a whole.

The leading troops of the invasion force crossed the English border on 8 November 1745. The walled town and castle of Carlisle submitted on the 15th, and thereafter the Highland Army made rapid progress through the English north-west. The London government summoned up reinforcements from the British Army in the Netherlands to meet the threat, but the redcoats were consistently out-marched and outmanoeuvred by the Highland Army, which was much better at coming to terms with the severe weather. In such a way t...