![]()

CHAPTER 1

In the Beginning

The prehistory of Japan is shrouded in myth and legend, but once upon a time when the world was still young the Sun Goddess Amaterasu was appointed ruler of the heavens. Her brother Susanowo was very violent, so the gods banished him to the earth. Amaterasu was frightened and hid in a cave along the coast. All the earth was plunged into darkness and the raging seas lashed upon the rocky coastline. The bewildered gods endeavoured to persuade Amaterasu out of her cave but were unable to do so. So they decided upon trickery. Placing a mirror and necklace on a nearby tree, they hoped the sun goddess would be enticed out. Amaterasu from within her cave saw the reflection from the mirror. Going to the entrance and nervously stepping onto the shoreline, she walked towards the tree. Immediately the ambushing gods seized her, and once again sunlight bathed the countryside and seashore. Meanwhile her brother had killed a monster and among its eight tails found a sword, which he had presented to his sister out of affection. Therefore, it happened that the grandson of Amaterasu descended to rule Japan, taking the three sacred treasures as the Imperial regalia. Eventually the great-grandson of Amaterasu, the Emperor Jimmu Tenno, ascended the Imperial throne in the year 660 BC. Thus, the line of Emperors was of divine origin, as were those related families of his personage, and with his peoples he sustained a special relationship.

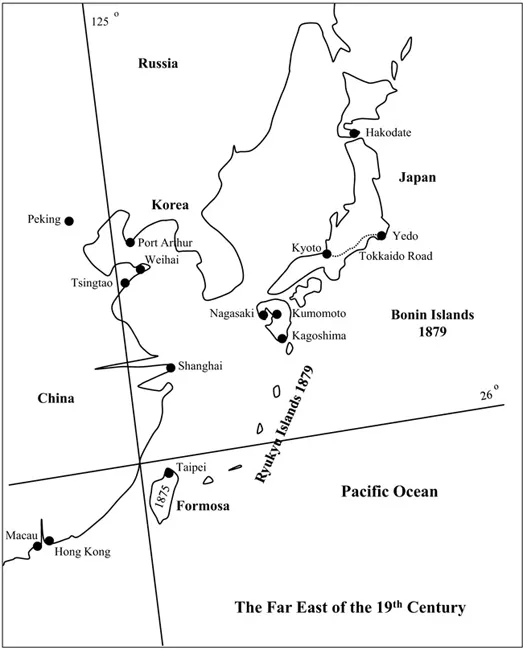

Through civil war, saved from the Mongolian invasion by the kamikaze, or Divine Wind – a typhoon in 1381 that scattered the Barbarian fleet of ships – Japan had survived and prospered. Japanese trading ships sailed from the southern ports of the Home Islands to the South Seas, to India and China. International trade prospered, but meanwhile the Tokugawa Shogun, the ruler, had gained complete mastery of the four Home Islands, making the Emperor an impotent puppet confined to the Imperial Palace in the city of Kyoto, and strictly controlled by the Tokugawa family. The shogunate had developed into an office that combined the authority of a prime minister with that of a commander-in-chief of the armed forces. Thus, all the power was in the hands of this one family for approximately the next two hundred years.

Contact with European influences and peoples came when a Portuguese ship, lately out of Macao, the Portuguese settlement on the China coast, was wrecked on the south coast of Japan. The ship, having been blown off course for days, was hurled across the sea amid a raging storm of white-capped breakers set against a darkened sky in which the thunderclouds stormed away over the heavens. Through the torrential rain, the ship had staggered from wave crest to deepening trough, the crew desperately clinging to the crumbling timbers with all shrouds blown away long ago. Suddenly, when all seemed lost, the survivors and what remained of the ship were violently hurled onto the shores of the subtropical coast of southern Japan, somewhere along the shores of Kyushu. This was a fortunate accident, indeed, for the survivors, who were warmly welcomed. The Japanese thereby acquired the new European muskets, which their gunsmiths promptly reproduced with much artistry. In the following year of 1549, a Japanese privateer landed in southern Japan, bringing the Jesuit St Francis Xavier to the Home Islands. Immediately the Jesuits set about converting the people. Soon the Roman Catholics could claim over a quarter of a million Japanese converts. The Shogun saw the conversion to Christianity as a political advantage when the Spanish friars landed and a Spanish seaman was heard to say that Spanish conversion to Christianity had been but a prelude to Spanish empire building in the Americas. The Japanese political establishment took a contrary view most seriously. But eventually the Shogun looked upon Christianity as a dangerous, disruptive, political menace combining revolutionary ideas with dangerous practices. Repressive measures followed, leading to the crucifixion of six Franciscan priests in 1597. By 1614, there was a general policy of purging Christianity in an endeavour to persuade those converts to renounce their religion – the religion of the Barbarians! The height of the persecution came in 1637, when 37,000 Japanese Christians fled to Shimoshima, where the Shogun besieged them and a Dutch ship bombarded them. Of course, the end was inevitable. All 37,000 souls were slaughtered, a fate from which they were unable to escape. But by the grace of God Christianity in Japan was not to die out; it lived on, and to this day, a memorial may be visited commemorating this terrible event in that part of Japan. International trade brought not only St Francis Xavier and the Portuguese but also the Dutch in 1609 and British merchants in 1613. Meanwhile the Tokugawa shogunate determined upon drastic measures to rid the Home Islands of the Western Barbarians. Japan was to become self-sufficient, and international trade would have to go. As a result, the British merchants withdrew completely in 1623; the Dutch fared better, being banished in 1668 to Decimo, a small island in Nagasaki Bay. Here they might do business with Japanese traders once a year, and no more. The Spanish merchants had previously left in 1624 and no one was to return for more than two hundred years.

The result of the reactionary policy of the shogunate was to prohibit the travelling abroad of any Japanese citizen for whatever reason. Likewise, foreign citizens were not allowed to land on Japanese soil, and foreign sailors, if shipwrecked, could be executed. Thus, the lucrative trade with the Spice Islands from the sophisticated cities of China and the teeming land of India was cut off. Japanese merchants who could remember the good old days of high living, the overseas riches, the new and exciting foreign ways, had to start all over again. It was forbidden to construct large ocean-going ships. The Daimyo of Satsuma, the overlord of Kyusho and the Ryukyu Islands could build only small fishing boats for coastal trips and inshore fishing. Thus, Japan was totally isolated from the outside world. In the realms of religion, a compromise was established by the usage of classical Buddhism and chauvinistic Shintoism. The net result was that the Barbarians and Barbarian ways were effectively blotted out from the Japanese way of life. For 250 years, Japan was to enjoy an isolated peace, a Golden Age in which literature and the arts were to flourish side by side with the simple life. The classical Noh dramas of Chinese origin to Bunraku puppet theatre with plays written by Chikamatsu Monzaemon, the Japanese Shakespeare, and Kabuki plays concerning historical, domestic and dance dramas were brilliantly developed. Wood-block printing, called Ukiyo-e, was brought to a high standard, producing prints for humble people beyond the confines of the Imperial court. In the field of literature, novels by Saikaku became renowned, with a resurgence of the art of the poem, such as the haiku style, with its references to one of the seasons and no more than ten words. The most famous haijin was a poet known as Basho, who lived in the late seventeenth century. However, just before the descent of the ‘Purple Curtain’, Will Adams, a former crewman of a Dutch ship, had been wrecked on the southern coast. Making friends with Ieyasu Tokugawa the Shogun, Will Adams had been persuaded to settle in Japan, remarry and teach the Shogun all he knew of navigation. This Adams had done, being known as Miura Anjin and becoming the pilot major of a fleet of five sailing ships. Thus the first Japanese Navy had been formed sometime in the 1640s. Upon the death of Adams a shrine was erected – the Kurofune (Black Ship) Shrine to his memory on the site of the house in which he had lived.

During the seventeenth century, a rapid expansion of trade took place all over the Far East. American traders had relations with China, and Russian settlements were appearing along the eastern coast of Siberia. Then in 1839 Commodore Beddle USN attempted to negotiate a trade treaty with the Shogun. Unhappily in Japanese eyes, the Commodore had lost face in failing to discipline a Japanese seaman who had jostled the American commander. This resulted in complete failure. The Americans attempted a further expedition, announced in 1852, and in July of that year Commodore Perry USN, commander-in-chief and ambassador, arrived off the Japanese coast. America was not the only country interested in opening-up Japan to international trade, for also in 1852 Admiral Putyatin of the Russian Navy sailed into Nagasaki, arriving in October of that year to open negotiations, but without achieving any lasting success. Naturally, at the Shogun’s capital a political bombshell had exploded in that the Daimyo (the Lords) were asked to consider the American offer to negotiate a treaty. The aristocracy were split into two opposing factions: some were for ousting the foreigners, while others were for trading, and the unresolved question was still under debate when in February 1854 Commodore Perry returned with seven warships and 2,000 marines. Under such a display of naval power the Treaty of Kanagawa of March 1854 was but a natural outcome. The ports of Hakodate and Shimoda were opened for American trade and supplies.

Much of the opposition to the negotiations of the Treaty of Kanagawa was centred on the Satsuma clan, which was governed by a branch of the Imperial family named Shimazu, after an island port. These people were a seagoing principality in sub-tropical south Kyushu, the land of the Sun Goddess. They had borne the brunt of the Mongol invasion in 1274 when the kamikaze wind had scattered the enemy fleet. Ships had been provided by the clan in support of the 1592 invasion of Korea by the Shogun Hideyoshi. The Satsuma clan had conquered Okinawa and the Ryukyu Islands in 1609, and more ominously they were to lead the Strike South Faction in the 1930s, which culminated in the 1940 Pacific air and sea campaigns. Across the Straits of Shimonoseki lived the Shoshu clan in south-west Honshu, who had supported the Satsuma during the Korean invasion and controlled 11,000 hereditary lords; together with their neighbours, the Satsuma could muster 38,000 hereditary warrior lords. Both had opposed the Tokugawa’s policy of replacing external aggression with internal consolidation. As a consequence both had lost much land to the Shogun during the seventeenth century as a price for their views. During a much later act in the play, both clans would lead decisive roles in the story. For the time being, both clans opposed the Shogun’s policy, strongly objecting to the presence of the foreigners on sacred soil. The powerful clans of Satsuma and Mito organised violent, lawless groups of men to oust the foreigners by firing on the legations and pursuing a policy of assassination of Western diplomats and merchants. These violent killers were called Ronin, or ‘wave men’ – that is, they were tossed from venture to venture because all their clan loyalties had been lost. To the Westerners these Ronin were swaggering, reckless, two-sworded assassins and former samurai. At this time throughout Japan the cry ‘sonno-joi’ was heard, meaning ‘Revere the Emperor! Expel the Barbarians!’ The national cry was heard from island to island. Meanwhile the Emperor Komei had become obsessed with the idea of driving out the Barbarian foreigners, and this ideal was supported by the Lord Shimazu. Sometime previously Prince Asahiko had been in trouble with the authorities, and the Lord Shimazu had been able to obtain the release of the Prince. This was important, for Prince Asahiko had direct access to the Emperor. Furthermore, the Prince believed the old order was good enough and modernisation was undesirable. Unhappily the Prince wished to rid the Imperial court of the Choshu leadership – the very neighbours of Lord Shimazu. However, they were able to persuade the Emperor to cancel some of the powers of the Tokugawa Shogun, and a policy of intimidation of foreign colonists was officially initiated. During 1860 the first Japanese diplomatic delegation departed from the Home Islands to take up posts abroad in the United States of America. The American government had placed the US Navy cruiser USS Powhatan at the disposal of the Imperial government. For the first time the Hinomaru was flown from the masthead of the American warship. The flag was a red sun disc on a plain white background, which became the national flag flown on all Japanese warships and land bases. As the American cruiser left the sheltered waters of the inland sea and the summit of Fujiyama disappeared below the horizon, the fanatical Mito clan murdered the Gotairo, or Prince Regent, sometime during the course of 1860. This far-sighted man had negotiated the original Treaty of Kanagawa with the Americans and had advocated the opening-up of Japan to foreign traders. The Mito clan had attacked the legations and killed Henry Heusken, the US Consul. The acts of the Mito clan and the Barbarian Expelling Party had consistently been supported by Prince Shimazu Saburo of Satsuma since the first visit by Commodore Perry in 1852. Shimazu was a political moderate who was proud, courageous and authoritarian, but nevertheless believed in a reconciliation of the Shogun and the Mikado. He came to be of the opinion that Western technology possessed too much potential to be easily dismissed out of hand.

Conflict on the Tokaido

It had been the policy of the shogunate to ensure the wives and families of the Daimyo should live at court while their husbands attended to business on their estates. This had been enacted as an insurance policy against would-be usurpers of the Imperial state, and in accordance with custom Prince Shimazu Saburo of Satsuma rode out onto the Tokaido (East Sea Road) from Edo (Tokyo) to Kyoto. The prince was escorted by servants and samurai guards on his way to the Emperor’s capital at Kyoto. In magnificence the procession rode down the road. The grooms on foot tended the horses of the Daimyo and his servants. Before and aft of the important personages were the mounted samurai equipped with two swords. As they rode, the sun twinkled on the personal armour and sword scabbards of the guards. The jackets of the servants and grooms were emblazoned with crosses within circles on sleeves, jackets and scabbards. As the pageant progressed through village and town, all citizens made way for the Daimyo and his entourage, as was required by the law of the day. Upon nearing the village of Namamugi, the escort commander noticed two European gentlemen and a lady riding on horseback in the opposite direction to the cavalcade. Naturally he had no reason to suppose the law would be flouted by the European Barbarians, for the legislation was quite clear. The horses taking Prince Shimazu of Satsuma gaily trotted forward. The houses of the village were now in sight, and the road commenced to narrow as it went through the village. The European riders foolishly continued, to the consternation of the servants, who gesticulated to the foreigners to turn back or at least to stand aside. Now the European party consisted of three English men and an English lady out riding enjoying the countryside. There was Mr Charles L. Richardson, who proposed later to return to England on leave as a merchant from his business house at Shanghai, and had come over to Japan to meet some old friends. With Mr Richardson rode Mrs Borrodaile, a lady on holiday from Hong Kong and the sister-in-law of Mr William Marshall, an English merchant from the city of Yokohama, who had been accompanied by his colleague Mr Woodthorpe Clarke. Both these latter gentlemen had been instrumental in establishing the Yokohama Municipal Council sometime in 1862. The area around Yokohama had originally been a marshy, desolate region given over to the Europeans for the purpose of organising a trading post. Gradually a town had grown up almost along Western lines, and the more republic-spirited members of the citizenry, mindful of the dangers of immorality and the surrounding lawlessness, had determined upon the enforcement of law and order in each field of municipal activity. Thus Yokohama never did recognise the Emperor’s law, and local organisation was run exclusively along European standards. Meanwhile the three English merchants and their lady guest had been at dinner. Everyone had been entertained by Mr Richardson’s views and comparisons of trading conditions experienced in Japan compared with those existing in the city of Shanghai, China. After coffee and the completion of dinner, the party had quite naturally determined upon a breath of fresh air and a little light exercise. Horses were saddled and riding habit donned, and leaving the comfortable sanctuary of the guest house, the lady, accompanied by the three gentlemen, rode away to view the scenery with the prospect of an enjoyable afternoon’s gallop.

The four riders came on down the narrow Tokaido and presented a problem to the guard commander of the Daimyo’s entourage travelling the opposite way. He realised that the Europeans had broken the Emperor’s law and was determining what to do. An argument had commenced regarding dismounting and the right of way. Shouting broke out as the grooms violently gesticulated, the escorting horsemen scowled, and suddenly, like a flash of lightning, a samurai reached with his sword and slashed Mr Richardson across the side. The victim screamed in burning pain, his terrified horse panicked and turned about, Mrs Borrodaile, amid the uproar and equally terrified, strove to escape. In her attempt a samurai slashed at her long hair to obtain a souvenir, but the lady and horse sped away screaming in fright to Yokohama, leaving a bloodstained scene. Meanwhile, both Mr Marshall and Mr Clarke had been attacked and were lucky to escape with nothing more than sword slashes on the shoulders and about the sides. The Prince of Satsuma attempted to restore order amid the disorganised mêlée, and once again the entourage was able to proceed in an orderly fashion to the Emperor’s capital. In the meantime the dying body of Charles Richardson ended up under a tree at the roadside. A charitable peasant had taken the body into care, and commenced to nurse the broken and shattered man. But shortly afterwards a samurai warrior returned to the little house occupied by the charitable peasant and the dying Richardson. Raising his sword, the samurai struck a death blow that put Richardson out of his agony. The remains of the dead man were buried somewhere along the roadside.

Eventually Mrs Borrodaile rode into Yokohama, bloodstained and hysterical, to break the horrible news. The news spread like wild fire through every European section of the town. Every able-bodied Westerner, military and civilian alike, took out his weapons; revolvers were reloaded, swords were made ready in their scabbards. Saddling up, everyone was determined to ride off in hot pursuit. Lieutenant-Colonel Pyse of the British Consulate, Kanagawa, rode out with the Legation escort. Also present in the contingent were French, United States, Prussian and Dutch marines with two doctors. The armed party advanced down the road from Kanagawa to the village of Namamugi with care and in combat order in case of an ambuscade. Naturally the body of Richardson was not found, but the partly mangled remains were discovered near a grove of trees on the roadside. On investigation they learned that Richardson had painfully crawled to a nearby tea shop and pleaded for water, after which he met his end as described above. At about this time, Marshall and Clarke, dreadfully wounded and covered in blood, arrived at the United States Legation at Kanagawa. By now the Prince of Satsuma’s entourage had arrived at the court of the Emperor at Kyoto. Prince Shimazu paid his respects to his Imperial Majesty, and after a brief stay left for Kagoshima, his clan capital, suspecting a swift British reprisal.

Evening had descended upon the warehouses, offices, clubs and houses of Yokohama. The posse had returned from the village of Namamugi in great excitement, with revenge in mind. After dinner, when tempers had cooled, the British Chargé d’Affaires sent round orders for disbanding the British contingent, and instructed all to go home. It was made quite clear that only diplomatic channels would be used to solve this international incident. Nevertheless, the municipal authorities were not so complacent as the British Chargé d’Affaires. The marines were ordered to patrol the streets of Yokohama during the night in case further activities should take place. By the grace of God the evening was spent peacefully. However, a few months later after the report from the British Chargé d’Affaires at Yokohama had been received by the Foreign Office in London, Lord John Russell had issued an official demand on the Shogun’s government for the payment of £100,000 in reparation for the murder of Richardson. The government in Edo (Tokyo) was left in no doubt as to the feelings of Her Majesty’s Government, in that severe measures would be taken if the reparation was not paid within twenty days; also, that the assassins were to be arrested, tried and finally executed. The Prince of Satsuma would be required to pay a further £25,000 to the injured parties and the relatives of Mr Richardson. On receipt of the demand, the Tokugawa Shogun felt forced to pay: even if for no other reason, the overwhelming collection of heavy firearms would have persuaded the shogunate otherwise.

Retribution from the sea

Sometime in January 1863, Prince Asahiko celebrated his 39th birthday and invited Lord Shimazu to a party, with Konoye Tadahiro as guest of honour. During the course of the festivities Prince Asahiko and Lord Shimazu, in the presence of Konoye Tadahiro, had pledged eternal friendship. A bond had been sealed between the Imperial house of Fushimi and the aristocratic house of Satsuma. Touchingly enough, this e...