![]()

Chapter 1

The Auxiliary Territorial Service – ATS

The women's branch of the army during the Second World War was the Auxiliary Territorial Service, or ATS. It was created in 1938 and existed until February 1949, when it became the Women's Royal Army Corps (which itself was assimilated into other corps in 1990). The ATS had its origins as a voluntary service, the Women's Auxiliary Army Corps (WAAC), formed in 1917, its members working mainly as clerks, telephonists, cooks and waitresses. This was something of a watershed since, for the first time, women offered their services in a non-nursing capacity. The WAAC was renamed the Queen Mary's Army Auxiliary Corps in 1918, but it was disbanded in 1921.

During the Second World War, apart from nurses, who joined the Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMS), and medical and dental officers, who were commissioned directly into the army, all women in the army joined the ATS. The first recruits worked as clerks, cooks and storekeepers, but as the war progressed, their job opportunities were expanded to include drivers, ammunition inspectors, postal workers and orderlies. Women weren't allowed to take part in active battles, but as the shortage of men became acute, ATS girls were able to take on more demanding support roles such as radar operation, anti-aircraft guns and the military police.

By September 1941, there were 65,000 members of the ATS, and by VE Day in May 1945, some 190,000 women had joined the service. The most famous members of the ATS, and clearly they were glamorous role models who would have influenced many a girl deciding which service to opt for, were Princess Elizabeth (later Queen Elizabeth II) and Mary Churchill, the youngest daughter of Winston, the then prime minister.

In this chapter, we'll hear from ATS girls who served from the convoys in Britain to the momentous battle of Monte Cassino.

The Women

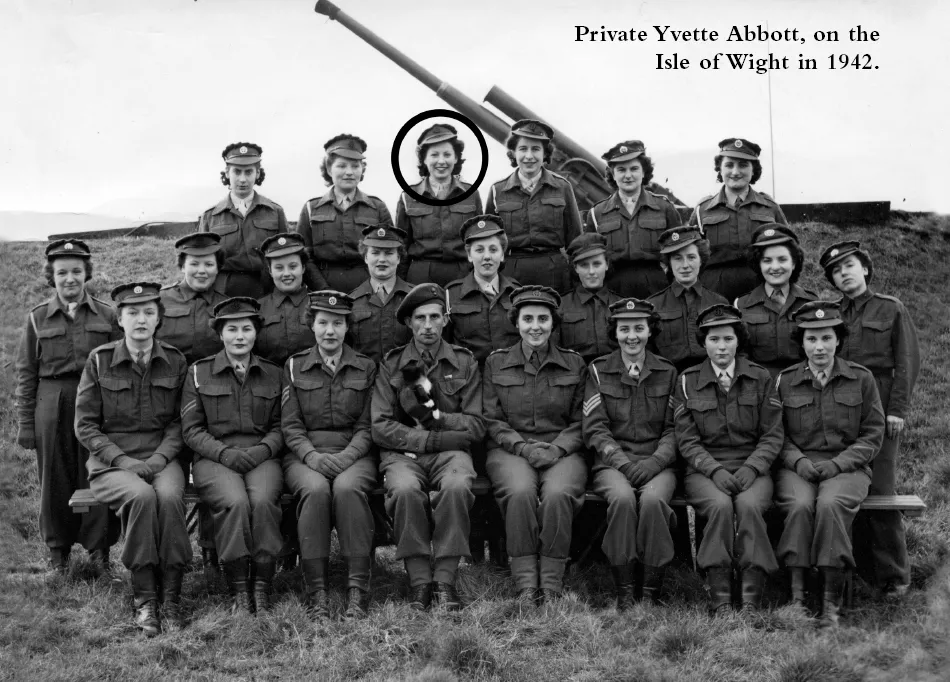

Private Yvette Abbott

Private Abbott was one of those amazingly brave women who worked on the anti-aircraft batteries, aiming to shoot down German bombers or even the bombs themselves, such as the V1s and V2s which were sent across the Channel. Posted to Portsmouth when the Blitz there was at its height, Private Abbott was exposed to danger as she and her colleagues searched for and plotted the enemy aircraft as it swooped down with its lethal payload.

I was born in London, in 1924 and I was an only child, unfortunately. I went to a boarding school for a few years at Abingdon in Berkshire, and it was after there I finished school because the war broke out. In some ways I suppose it was quite a good preparation for being away in the forces. At the beginning of the war, my mother and step-father had moved down to Devon. I was sixteen and I worked in Exeter in a dress shop and I quite enjoyed that. I really wanted to go into the Navy to become a Wren because I liked the uniform, but there was a two year waiting list, so I ended up in the army. I joined up at Honiton in Devon and was there for the start of [my] army career, where they gave you an induction course and so on, and you learnt to march.

The [other girls were] very varied; all sorts, all kinds we had. But it really taught me [about] both sides of life. I'm really quite pleased at having been in the army because that helped me enormously: I was a very shy little girl when I first went in and it brought me out. I was very quiet, didn't know anything about life whatsoever. In the army, you had to either join in or be left on the outside, so eventually I gradually learnt to become more confident with myself. I started to learn to live with people who had come from a very poor family, and with those that came from very high up. You learnt to mix with the different people, and, in fact, much later on, I learnt my first lot of bad language. I had never heard bad language till I went to the army!

From Honiton, they sent you all out to different places and I was sent to Oswestry, where they built these ack-ack batteries1 and made them up there. I learnt the instruments behind the guns – the height-finder and the predictor and plotting and so on. I was allocated to spotting at first.

The spotter used a Telescopic Identification (TI) which consisted of two sets of eye pieces at either end of a bar, which sat on top of a tripod. By looking into the eye pieces, the spotter could locate an enemy aircraft and call the range and bearing for the height-and range-finders to pinpoint and more accurately define its location. One of the great skills of the spotters was the identification of aircraft, and they had relentless training in order to ensure that they correctly spotted friend from foe.

I hated every minute of it because you're standing in the compound behind the guns gazing up at the sky, bored out of your mind. You had to remember which was a German aircraft and which was an English aircraft, which I found very difficult anyway. But it was so boring, and I pleaded with them to let me go on something else, so they put me on the height finder for a little while. For that, you get the height of where the aircraft is above you. Then you relay [the information] to the guns through the predictor. Eventually, I landed up on a predictor which I liked mostly, and I did a little bit of plotting as well.

The height- and range-finder consisted of two telescopes in a long base tube. Different types were used, but the Barr & Stroud instrument was 18 feet long. The operators used eye pieces to look through and pinpoint the aircraft, taking height and range, and sending this to the predictor.

The predictor was an instrument used to calculate how far in front of an aircraft the gun would have to fire in order to explode close enough to the aircraft to knock it off course. Using the information from the height- and range-finder and the calculated speed, the operator would look into the eye pieces to see a small image of the aircraft. They would then turn dials to keep the image in place, and once they were ‘on target’, the information was automatically fed to the guns, which would then be fired.

The predictor was a great big funny old thing. It looked a bit like a sort ofTardis really, and it had all these dials on it. You had these little handles that you had to wind quickly round to keep the needle going with the dial, because the information came into the predictor. You had to follow this very carefully, and all that information was then sent out to the guns. This was [part of the] training, and then we had to go up to a firing camp in Anglesey, right out in the wilds, to learn how to actually make the guns fire, or to help the guns to fire. We had a radio-controlled aeroplane there, which pulled this long sock behind it. We were supposed to hit the sock, and we were warned that if we hit the aeroplane, it would cost an enormous amount of money to replace it, and we very nearly hit it! We managed to get the sock once I think, but it was tremendous training. It really was; it was very good. It was left to the men to manhandle and move the guns around; our side of it was very much less physical.

The [next] posting was down at Portsmouth and it was one of the nasty ones, because Portsmouth being a big naval port, the Germans were well after that, so we had an awful lot of raids down there. And that was quite frightening. We were right on the edge of the naval base – it was a big high bank with a rail going down, and we used to see them taking the torpedoes down to the submarines.

It was pretty noisy when those guns went off, because they were big chappies, and we didn't have any protection against the noise at all – we just put up with it. I would say we didn't have a heck of a lot of success [shooting down German planes], only occasionally. But I suppose the very fact that we were sending up shells helped to keep the Germans away a little bit, perhaps.

The raids were mostly night time but we did have some daytime ones – in fact, we had quite a few daytime ones when I think about it. One of the little Tiger Moths got hit by a German plane and he came down into our camp. It was very sad because he was a very young pilot and we could see him. He was out for the count in his cockpit and it was all aflame. We made a long line of buckets of water to try and put the thing out. One of our sergeants, he was wonderful; he got right up with an axe and axed this poor guy out of the plane. He was alive but only just. He didn't know what was going on fortunately, but as they pulled him out, his feet came away, which was very nasty. Then they took him off by ambulance, but he died on the way to hospital. Just as well I think. But it was a very sad thing, that.

The raids were horrendous. We had quite a few near-misses with bombs, sometimes when we were in the billets. And we used to hide under our beds because it was so noisy and we could hear something coming. You could hear the whistle of the bombs coming down. We didn't know where it was going to land so we sometimes got underneath our beds if we weren't near enough to the subway thing that we went underneath to. We did have an air raid shelter, but sometimes you weren't near enough it. Fortunately nobody was killed on my base. How they missed us I do not know, because we were right there by the port with searchlights going as well.

Whilst I was there, they caught a spy on our camp. There was a lot of activity going on round the guardroom. We didn't know what was going on at the time, and then we heard later that this guy came up to the camp and said could he come in and see the captain or the major or somebody. One of our very astute chappies on guardroom duty looked at him and happened to notice that the pips on his shoulders were on upside down – he had come in as an English captain. I didn't know they could be upside down, but that's what we were told. And so he thought,‘Hello, something's up here’, so he reported it. All the big wigs went down and had a look, and discovered eventually that he was a German spy. So that was quite exciting. I didn't actually see him. I was longing to see him, of course. We were all longing to see him, but they bunged him straight into the prison behind the guardroom; and then he was carted away by, I suppose, Secret Service or whatever.

I was in Portsmouth for about a year, and then I went to the Isle of Wight. The raids were still going strong and we seemed to get these Stuka bombers diving down, with that scream that they used to come down with. They used to come and try to dive-bomb us while we were there, but we were just above Cowes at the time. The guns I remember that we were on were 5.5 [calibre],2 I think it is – I was always on the big ones. Cowes was absolutely the same [as Portsmouth]. You were in Nissen huts, of course, to sleep and we had the gun emplacements and so on, so it was exactly the same, really.

We started to notice that there were a lot of flashing lights going on across a field and everybody kept saying, ‘Have you seen those lights over there keep flashing away?’ Our army guys went over there to try and investigate. They went very quietly, apparently, to watch, and then they discovered that there was somebody flashing lights when it was dark, when the Germans were overhead. So they called the police and also some [authority] to do with the Army, I suppose, and this guy was caught. He was a German spy who had obviously been relaying all the information, probably about our gun emplacements to his ‘friends’! It was quite exciting. Of course, there was an awful lot of twittering going on, you know, and everybody was very excited about it. We thought,‘Oh gosh, we've actually got a spy on the edge of the camp’. So that was the second time I got involved – well not involved exactly, but …

We did have a bit of time off, though, which was allocated to us. You could have a day off a week or something, or an afternoon, or whatever it might be, depending on how much was going on. We used to go down into Cowes and go to the cinema and the fish and chip shop. That was where I met my husband actually. There was a row going on – some naval guy came out and pinched somebody else's chip as he came out of the door. My husband came round and very gentlemanly-like said, ‘Oh, let me move you over here, we don't want to get you involved in the fight’. He was a sergeant in the marines and they'd come over for a big exercise. They were supposed to be taking over the Isle of Wight, you know, and we all had to be trying to stop them.

I was a private, and then on the Isle of Wight, I became a lance corporal. Well, then I blotted my copybook by coming in late twice, and so my stripes were whipped off me, and I just stayed as a private to the end of the war. I was quite happy as a private. I did ask if I could go and become an officer, but when they interviewed me they said, ‘Well, we don't really think that you're ready to be officer material’. I think they were politely telling me that I definitely wouldn’t become an officer!

I was there a good year and a half and then we were pushed over to Raynes Park [south-west London]. They had made this gun emplacement in the big park up there, and that was when we started to encounter the doodlebugs3 and the horrible things that the Germans were throwing at us at the time. It was a bit late to shoot them down over Raynes Park, really, but [the authorities] were just trying hard. I mean, this was before they realised that the doodlebugs were coming in too low, and that we had to stop. I think they realised then that the guns had to be so low that we were going to be knocking people's houses – you know, the chimney pots and things off the houses. And if we got them, they'd land on the houses. There was nothing you could do. It was horrible – when they cut their engines out, you didn't know where they were going to drop. Just the other side of our camp in the road there, one came down and, in fact, we were made to go over and help the people who were in there. There was one poor little old lady who was blind and she didn't know what was happening or what had happened. It was amazing that she didn't get hurt. We couldn't believe it, but we managed to get her out and they took her away to some place for them to look after her. And poor souls, some of them were killed; the houses were just smashed to pieces. It was dreadful really. By then, the conventional raids had more or less ceased and it wasn't so bad then. So apart from trying to hit the V1s, which was difficult anyhow, there wasn't so much for you to do. That's why they decided to put some of the ack-ack batteries down out into Kent to catch the bombs before they came in. But we didn't get the chance and we all got split up into different places, which we were all very u...