![]()

Chapter One

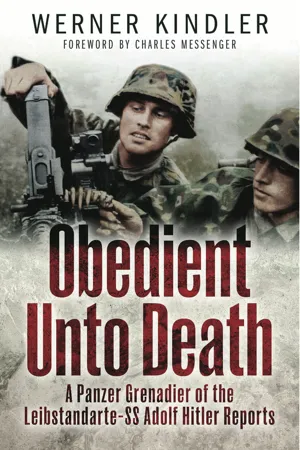

From a Farm in Danzig into the Leibstandarte-SS Adolf Hitler

I was born on 15 July 1922 at Kottisch in West Prussia, the first son of farmer Otto Kindler and his wife Elisabeth. He had served the Kaiser in the First World War as a soldier on the Düna. I grew up on the family farm with two sisters and a brother born in 1928. Kottisch, founded in 1818, lay in the Preussisch-Stargard district of West Prussia. Geographically it lay west of the Vistula and south of Danzig. Amongst others, the town of Preussisch-Stargard and Dirschau fell within the region governed by the great Baltic port of Danzig. Kottisch was a small village, half-gutted by fire in 1888. When I was a boy, the village had thirteen independent German farms. Shortly before my birth, my West Prussian homeland was severed from the territory of the German Reich and ceded to Poland under the victors’ dictates of the Treaty of Versailles. From 1920 Poland exercised full control over West Prussia. Three-and-a-half million Germans therefore came under Polish domination whether they liked it or not. West Prussia now formed the so-called ‘Polish Corridor’. This was the former part of Germany, now Polish, through which one was obliged to drive in order to get from Germany to the German province of East Prussia. The great Hanseatic port of Danzig was now controlled by the League of Nations.

In 1931 Germany estimated the presence of 1,018,000 persons of German racial stock in the Polish sphere of influence. As a result of the prevailing pressures, at the census 277,000 persons had preferred discretion to claiming they were Germans. Since Poland had been given West Prussia in 1920, over three-quarters of the original German population had left, and the remainder were to be oppressed and ousted in a long campaign aimed at forcing them to leave.1

By 1924, by means of liquidations, expropriations and compulsory purchase, Poland sequestered 510,000 hectares of land, to which by 1939 they had added another 1.2 million acres through so-called ‘agrarian reform’. A whole string of laws and decrees, the worst being the notorious ‘Frontier Zone Law’, was created to dispossess and expel the Germans or deprive them of their legal rights. German miners and employees in Upper Silesia subsisted on meagre incomes, and in thousands of cases faced starvation. Men of the Hela fishery, established for centuries, suffered similarly.2

I grew up on the parental smallholding. Our family was cut off from the great economic and generally improving tendencies in Germany. From 1928 by Polish law I was obliged to attend the Polish village school at Kottisch, from where I went to German secondary school in Preussisch-Stargard until 1938. Germany under the Hitler regime considered it a matter of overriding importance to return to the Reich those Germans expatriated beyond its borders, and to reincorporate the occupied regions severed from the Reich by the Treaty of Versailles. In 1938 Austria and the Sudetenland were annexed to Germany. Tension with Poland over the West Prussian Corridor and the Free City of Danzig grew. In 1939, the German Foreign Ministry suggested to Poland that the time was now ripe for Germany and Poland to come to a general agreement over all existing problems. The German proposals were as follows:

1. The Free City of Danzig should return to the German Reich.

2. An extraterritorial autobahn and extraterritorial multi-track railway line would run across the Corridor.

3. In the Danzig region Poland would be given an extraterritorial highway or autobahn and a free port.

4. Poland would receive marketing guarantees for its products in the Danzig region.

5. The two nations would recognise and guarantee their common frontiers or the mutual territories.

6. The German-Polish treaty would be extended by ten years to twenty-five years.

7. Both nations would add a consultation clause to their treaty.3

Poland rejected all these proposals outright and ordered a general mobilisation, relying on the British guarantee of 31 March 1939 for support, and on 3 September 1939 Britain and France declared war on Germany.

In that calamitous summer of 1939 I celebrated my seventeenth birthday on 15 July working on my parents’ farm. The Polish attitude had become more hostile. Polish radio and newspapers were stirring up feelings against the Germans again. On 26 June 1939 a Polish newspaper published a letter showing Poland’s territorial claims. After the Polish attack on Germany, the new Polish border would extend from Bremen through Hannover, Fulda, Würzburg and Erlangen, cutting Germany in half. A Polish ‘Western Border Union’ (West-markenverein) circulated a huge number of maps and postcards showing those parts of Germany to be annexed to Poland.4

Because of this agitation, Germans were attacked and killed in West Prussia and other regions. Especially from August 1939, larger numbers of Germans began to be kidnapped by Poles and murdered. German schools were closed by the Polish authorities. My own village escaped these attentions, although elsewhere Fräulein Maisohle, one of my sister’s teachers, was killed. As I recall personally, in Preussisch-Stargard only a few kilometres away, several German businessmen were taken away and murdered.

Up to 21 August 1939 about 70,000 Germans had fled the state, but the terror even spilled over into German territory. Polish mounted units made repeated cross-border forays into German territory, killing farmers in East Prussia and torching their farms. For their protection the 57th Artillery Regiment was brought up from Königsberg to Garnsee/Neidenburg in East Prussia. On 26 August 1939 a party from the German regiment intercepted one of these Polish raiding groups returning from such an incident on German soil and killed forty-seven of them.5

In the late summer of 1939 the pressure intensified, and after the Polish mobilisation my father had to find somewhere to hide his horses, wagons and coachman. In order to escape the Poles I went into the forests. The war began on Friday 1 September 1939. With my friend Siegfried Sell I cycled to Dirschau and next day came across an SS-Heimwehr Danzig MG post on one of the Vistula bridges. Finally, the first German soldiers! On 3 September troops of the German Wehrmacht liberated nearby Preussisch-Stargard.

In the middle of the following week the population was called upon to protect West Prussia. Men aged from seventeen to forty-five years were to report. I was amongst them and, under the direction of German police units, assisted in street patrols, guarding the municipal building and Preussisch Stargard prison. No uniform was provided but I was given a green armband with the word Selbstschutz (‘local militia’) on it to wear on my civilian clothing, and armed with a 98-carbine and a 7.65mm pistol.

On 6 October 1939 Poland surrendered unconditionally. This cancelled the local provisions of the Treaty of Versailles and West Prussia was reintegrated into Germany. My home village of Kottisch was renamed Gotenfelde and fell once more within the jurisdiction of Preussisch-Stargard which, from 26 November 1939, became part of the newly-formed Reichsgau (Reich administrative district) of Danzig-West Prussia.

During my short tour of duty with the West Prussian militia, at age seventeen on 13 November 1939 I was called up at Kloster Pelplin and sent to Prague for four weeks’ military training with 6th SS-Totenkopf-Standarte (SS-Colonel Bernhard Voss). At Prague-Rusin I met colleagues I had known in the Danzig militia.

This particular unit was the first of the Totenkopf-Standarten to have been set up in wartime. I went into No 9 Company, still in civilian clothing. The training at Prague was harsh. We were sworn in by SS-General August Heissmeyer on 16 December 1939 at the Heinrich Himmler barracks, Prague-Rusin.6 This is the oath we took:

I swear to thee, Adolf Hitler,

As Führer and Chancellor of the Reich

Loyalty and bravery!

I pledge to thee and to those placed by thee in authority over me

Obedience unto Death

So may God help me!

Two days after taking the oath I was transferred to No 2 Company, 13th SS-Totenkopf Standarte (SS-Colonel Klingemann) at Linz. My company commander was SS-Captain Fritz Holwein. We were 250-strong and composed mainly of men from Preussisch-Stargard, Dirschau and Karthaus. In February 1940 a rooting-out left only thirty-six of us in the company. All the others were discharged, most to be re-conscripted later.

We had harsh, intensive winter training in Upper Austria equipped with Czech weapons. I did not finish an NCO’s course. On duty one day the Company visited Hitler’s parents’ house at Leonding. In March 1940 the regiment moved from Linz-Ebelsberg to Vienna-Schönbrunn into barracks previously occupied by 1st SS-Regiment Der Führer. In Vienna my company commander SS-Captain Holwein took over the 6th NCO Training Company and was replaced by SS-Lt Hans Opificius. He was a much-liked commander who visited the men on many weekends with his two children. He lived with his family in Vienna. That April I got my first spell of home leave with my family in West Prussia.

In May 1940 they transferred me again to No 4 (MG) Company/13th SS-Totenkopf-Standarte to train on the heavy MG 08. At Vienna one of my instructors and also my gun-captain was SS-Corporal Hans Fuchs, a businessman and reservist from Franconia alongside whom I was to serve until 1944 in the same company. Another instructor was 40-year-old Professor Eckert who taught me how to make the best impression on NCOs and officers. On 15 July I celebrated my 18th birthday.

The 13th SS-Totenkopf-Standarte was disbanded on 15 August 1940. We held an ironic burial ceremony in the presence of its officers. My next drafting was to Holland, into the reorganised No 4 (MG) Company, 4th SS-Totenkopf Standarte, made up in the main of men from the same unit previously known as Ostmark. 1st Battalion was at The Hague, 2nd Battalion at Groningen and 3rd Battalion at s’Hertogenbosch. They put 4th (MG) Company in the Leopold School on the fishery dock at Scheveningen. Here I did infantry and weapons training in the sand dunes. We had only old MGs and the water-cooled heavy MG 08. For a change, we did turns of duty as coastal defence against expected British raids and we also blew up drifting mines by firing at the detonator horns. Unit welfare was outstanding, a hallmark of the admired battalion commander ‘Kapt’n Schuldt’. However, men up to eighteen years of age received no coffee, only milk and cocoa on Sundays; adults got morning coffee. In September 1940 occurred a high point in my service when I stood honour guard over a week for former Kaiser Wilhelm II, exiled to an estate at Doorn, and I did guard duty on three occasions for the visits of Göring to Wassenaar.

It was at this time – August 1940 – that Waffen-SS Command was formed and the Totenkopf-Standarten were absorbed into the Waffen-SS. The average age in the Standarten was high. To reduce it, the older reservists were released and the younger men transferred into the lower numbered Standarten 4 to 11 inclusive while the others were disbanded. The surviving Standarten then reorganised along the guidelines set for the motorised SS-infantry regiments, and in September 4th SS-Totenkopf-Standarte was also motorised. I spent a whole month at driving school and obtained my Class I and II licences. I was taught about vehicles and engines, repairs and oil-changing and got to know all the vehicles in service.

The year 1940 drew to its close. The Netherlands Reich Commissioner Artur Seyss-Inquart attended the Yuletide festivities of our No 4 Company. In February 1941 our regiment arrived by train in the Warsaw district of Mokotov. On 25 February we removed our Totenkopf collar patches and sewed on the SS runes: our unit was now known as the 4th SS Infantry Regiment (Motorised), and in May attached to 2nd SS-Infantry Brigade (Motorised). Thus I completed an 18-month period of training under what amounted to peacetime conditions; I was an infantryman competent to handle the light and heavy MG, and able to drive all manner of road vehicles. This training would stand me in good stead later, and now a major change was to occur in my military fortunes.

In May 1941, the companies of the 4th SS-Infantry Regiment paraded for inspection by officers of the Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler who had arrived in Warsaw from Wischau. Together with others I was selected for transfer into the LSSAH. That was the last I ever saw of the 4th SS-Infantry Regiment (Motorised).7 I joined the ranks of the Leibstandarte at Wischau that same month and became a member of the most famous German unit. By virtue of its military achievements the prestige of this strengthened regiment was on a level with the Prussian Guard units of earlier centuries, whose famed predecessors included the Guard Regiment of Foot, the Garde du Corps and the 1st Life Guard Battalion of the 15th Guards Regiment. As a further parallel to the Leibstandarte it is valid to mention that the most elite Prussian regiment, the Garde du Corps, founded in 1740 in squadron strength, fulfilled the role of personal bodyguard to Prussia’s king Frederick II. This corps, like the Leibstandarte, was composed of tall volunteers and was held in special regard in the Reich. Frederick the Great and the Prussian kings who succeeded him always had the privilege to be commander-in-chief of this regiment. Yet the Garde du Corps was by no means just for parades and bodyguard duty, for it fought with great braver...