![]()

INTRODUCTION

Navies in the twenty-first century exhibit significant changes from their counterparts at the time of the Cold War’s end, now a quarter of a century ago. Many of the major fleets that dominated the world’s oceans – deprived of longstanding core roles virtually overnight – are now much smaller than they were then. They have, over the same period, been joined by a new cohort of emerging naval powers, many located in Asia. These new fleets have been financed by the shift in world trade towards the broader Asia-Pacific region and justified by rising regional tensions.

However, change extends much further than this. The evolution of the global political order away from a bipolar stand-off between NATO and the Warsaw Pact (and their respective allies) has been accompanied by a period of instability which has brought new and different missions to replace those lost. These often require different types of warship, as well as changed methods of operation. Technology, increasingly derived from civilian applications in a reversal of the historic direction of travel, has also proceeded apace. This is, perhaps, most evidenced by the accelerating use of unmanned and autonomous vehicles. However, it has also had important implications for such wide-ranging areas as command and control, propulsion, stealth and manning. Meanwhile social change has been reflected in a decisive shift away from conscription towards all-volunteer, professional services and in the growing numbers of women serving at sea.

The US Navy Los Angeles class submarine Pasadena (SSN-752) prepares to undock from the floating dock Arco (ARDM-5) as the Arleigh Burke class destroyer Stockdale (DDG-106) departs San Diego harbour in January 2016. Although Asian fleets are of growing importance, the US Navy remains the world’s largest and best-funded fleet by a considerable margin. (US Navy)

Since 2010, Seaforth World Naval Review has chronicled some of these changes on a yearly basis. However, the short timeframe inherent in this approach is not necessarily the best way to identify and assess trends that might take a decade or more to emerge. Navies in the 21st Century therefore attempts to take a longer-term and broader perspective in describing both why and how fleets have evolved in the post-Cold War age. In doing this, the hope is to complement the periodic analysis contained in the Seaforth World Naval Review series with a more comprehensive assessment of why things are the way they are now. At the same time, as relations between Russia and the West cool once more as a result of events in Ukraine and the Crimea, the book aims to explain to a broader readership the current importance, objectives, structures and capabilities of the world’s major fleets.

Navies in the 21st Century follows the methodology established by the annuals in calling on recognised experts to elaborate on these key themes. This introduction aims to set the financial context to post-Cold War naval developments and outline the major areas addressed in subsequent chapters.

THE FINANCIAL BACKGROUND

One of the biggest factors influencing naval force structures across the world is inevitably the amount of money governments allocate to spending on the military. A good starting point from which to analyse global world naval development is, therefore, to understand this financial backdrop.

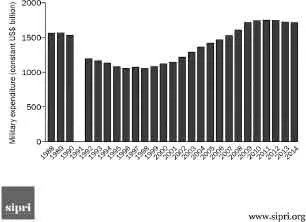

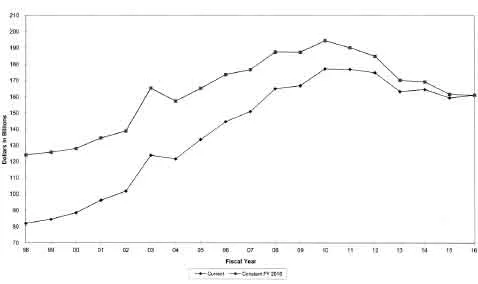

Global Trends in Defence Spending: In spite of considerable discussion about the post-Cold War ‘peace dividend’, it is important to appreciate that the world, at the start of 2015, was actually spending a little more cash on the military than it did at the end of the Cold War. This is graphically illustrated by Diagram 1.1, provided courtesy of SIPRI.1 Arguably, there are three main reasons for this:

The world – through the process of economic growth – is now considerably wealthier than it was twenty-five years ago. As such, although the

percentage of the world’s annual economic output – as measured by gross domestic product (GDP) – allocated to defence has fallen from c.4.5 per cent in 1989 to c.2.3 per cent in 2014, this still means that more cash is available. In 2014, nearly US$1,800bn was spent on the military worldwide.

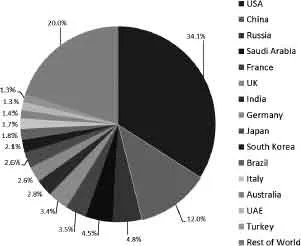

There has, indeed, been a ‘peace dividend’. However, this has largely been restricted to Europe and Russia. Elsewhere – particularly in Asia and the Middle East – continued regional tensions have meant that defence spending has remained a priority. Strong economic performance in many economically developing countries has also meant that they have been able to afford to spend more, both in absolute and relative terms. There has therefore been a shift in spending from Europe towards Asia. This is clearly demonstrated by Diagrams 1.2 and 1.3.

A big decline in United States’ defence spending in the decade after the Cold War was effectively reversed by the terrorist atrocities of 11 September 2001 and the onset of the ‘long war’ against terrorism. The huge expense of this war explains why the share of world military expenditure accounted for by the United States was little different at the end of 2014 than it was in 1989.

The British Royal Navy’s technologically advanced Type 45 air-defence destroyer Diamond escorting the Danish merchant ship Ark Futura in the course of Operation ‘Recsyr’, part of the UN-sponsored mission to destroy Syria’s chemical weapons, in 2014. The post-Cold War era has seen navies acquire new technology and adapt to a broad range of missions. (Crown Copyright 2014)

Although the impact of the world financial crisis that started in 2008 and a large government deficit have curtailed United States’ defence spending since the beginning of the current decade, it remains the world’s dominant military power by a considerable margin. The United States spends three times as much on its military as its nearest rival, China, and accounts for around a third of the world’s defence spending overall. It also remains by far the largest economy, being over two-thirds larger than China in nominal terms.2 Moreover, the United States benefits from a network of alliances with many of the other world’s major powers, which share a common interest in a global trading economy that relies on a stable international order. In spite of perceived threats to American dominance in Asia and elsewhere, it is difficult to perceive the basic status quo changing materially in the short to medium term. Equally, the US Navy looks firmly anchored to its position as the world’s dominant naval force.

1.1: World military expenditure, 1988–2014

1.2: The share of world military expenditure of the 15 states with the highest expenditure in 1989 (SIPRI)

1.3: The share of world military expenditure of the 15 states with the highest expenditure in 2014 (base data courtesy of SIPRI)

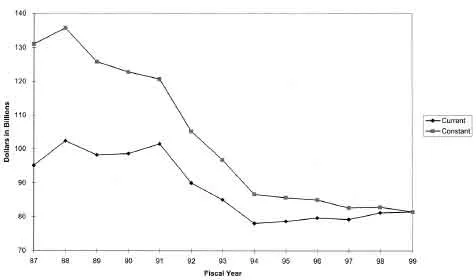

1.4: DoN FY 1999 Budget Estimates Real Program Trends

1.5: DON FY 2016 Budget Estimates Real Program Trends

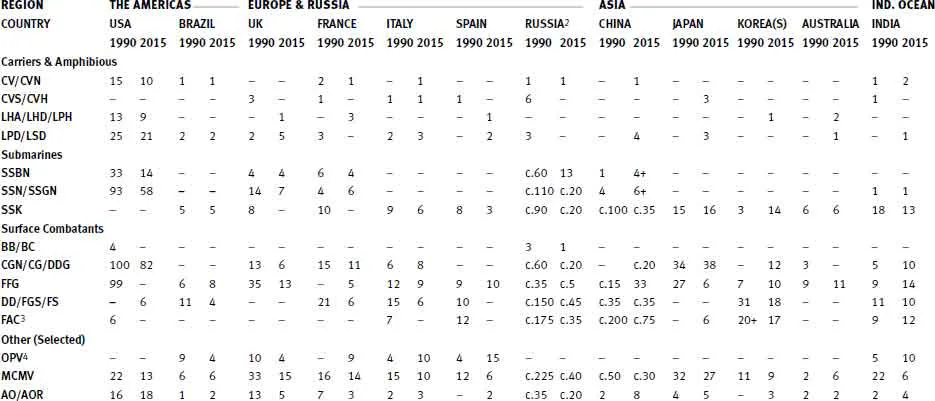

1.6: MAJOR FLEET STRENGTHS – 1990–20151

Notes

1 Numbers are based on official sources, where available, supplemented by news reports, published intelligence data and other ‘open’ as sources as appropriate. Given significant variations in available data, numbers should be regarded as indicative, particularly with respect to Russia, China and minor warship categories. There is also a degree of subjectivity with respect to warship classifications given varying national classifications and this can also lead to inconsistency.

2 1990 data refers to the Soviet Union, dissolved at the end of 1991. The precise status of the Soviet/Russian fleet at the end of 1990 is rather speculative, as many warships held in official reserve status never returned to operation.

3 FAC numbers relate to ships fitted with or for surface-to-surface missiles.

4 The lack of offshore patrol vessels for some countries reflects the existence of a separate coast guard for the performance of territorial constabulary roles. These can be significant forces.

Naval Expenditure & Force Structures: Of course, overall trends in and amounts allocated to military expenditure do not necessarily correlate to naval investment. A good case in point is Saudi Arabia, which currently has the fourth largest defence budget in the world but only a comparatively small navy due to the priority attached to land-based forces. Even when money is directed to the naval budget, this does not inevitably result in a more numerous or powerful fleet. The costs of new technology, ill-judged investment decisions and the need to provide adequate conditions of service and compensation to service personnel with growing expectations are just a few examples of factors that can eat away at naval funding.

Given its status as the world’s most powerful naval force, it is instructive to look at the development of the US Navy’s budget and force structure from the late 1980s with these perspectives in mind. Since then, it has shrunk from the near ‘600-ship fleet’ targeted during the Reagan presidency to somewhat less than 300 ships today. As defence expenditure remains close to 1980s levels, this decline inevitably warrants some explanation. The following factors seem relevant:

The Norwegian Fridtjof Nansen class frigate Thor Heyerdahl in company with other warships off the Nor...