![]()

CHAPTER ONE

CHRONOLOGY OF THE ROUTE OF THE LEICESTER GAP

Apart from its role in the story of signalling, the ‘Leicester Gap’ has no other historical significance. The section between Irchester in the south and Loughborough in the north formed just a small part of the Midland Main Line, named as such because it had been created by the Midland Railway (MR) as part of its trunk route between London, Sheffield, Leeds and Carlisle.

This main line had not been planned as a whole but evolved from, various at first, separately operated lines. The first of these to be completed was the responsibility of the Midland Counties Railway (MCR) who opened an isolated section of single track between Nottingham and Derby on 4 June 1839. By the following year the company had completed another line – this time double track – from a point almost midway between the two county towns (later to become Trent Junction) southwards through Leicester to a junction with the London & Birmingham Railway at Rugby. By this connection, passengers could travel by train between the Midlands and London, Euston Station. But from Derby, passengers already had another route they could choice to and from the capital that had opened on 12 August 1839 and was run by the Birmingham & Derby Junction Railway (B&DJR). Its line ran from Derby through Tamworth to another junction with the London & Birmingham Railway but this time at Hampton. In the first few years of operation, rivalry between the MCR and B&DJR drove fares down to such an extent that both companies came close to bankruptcy, only saved by their amalgamation on 10 May 1844 with the railway company that had operated the line north of Derby to Leeds since 1840. Thus the Midland Railway was born.

Over the next two decades, this ambitious new company sought to improve its connection to London by building new lines. All these new routes affected its existing main lines leading to the downgrading of certain sections and the creation of awkward junctions at Wigston, just south of Leicester and at Bedford. At the former the first of these new routes branched off close to the existing junction with the London & North Western Railway’s (LNWR) line to Nuneaton. The new line ran to Hitchin where a connection was formed with the Great Northern Railway (GNR). The line opened to goods on 4 May 1857 and for passengers four days later, but passenger trains continued to travel to and from Euston until an agreement was reached with the GNR that the MR could run through trains using its own engines all the way to and from King’s Cross. The first of these trains ran on 1 February 1858 after which the section of the former MCR main line from Wigston to Rugby was reduced to branch line status. Barely ten years later and the MR was poised to complete its own station in the capital – St Pancras, at the end of another new line this one leaving the Wigston-Hitchin line at Bedford where the re-arrangement of tracks created another unsatisfactory junction. Expresses began to run to and from St Pancras over the new route from 1 October 1868, after which the former main line section between Bedford and Hitchin was downgraded and then reduced to a single line in 1911 apart from the section between Southill and Shefford which remained double track.

The ‘Leicester Gap’, therefore, was formed of the Irchester-Wigston North Junction section, originally part of the MR’s new main line between Hitchin and Wigston North opened in 1857, and the Wigston North Junction–Loughborough section which once formed part of the MCR main line between Rugby and Trent Junction that was opened in 1840.

![]()

CHAPTER TWO

TRACK LAYOUTS

DOUBLE TRACK

The first very obvious change in operating practice after the new signalling in the ‘Leicester Gap’ was completed in 1987, was the overturning of the rule that trains travelling in the same direction were always run (except in special circumstances) on tracks not used by trains running in the opposite direction. [3] On the Midland Main Line in this area that meant trains going north were confined to either the down passenger, the down slow or the down goods lines, whilst those travelling south could only use the up passenger, up slow or up goods lines. (This, and related terminology is examined at the end of this chapter.) The special circumstances included, for example, when single-line working was necessary due to engineering work. The new signalling of 1986/87 was so arranged that trains could be run at any time if needed in either direction on any line – ‘bi-directional running’, a practice that was soon to become common on many other routes throughout the country as those lines were re-signalled.

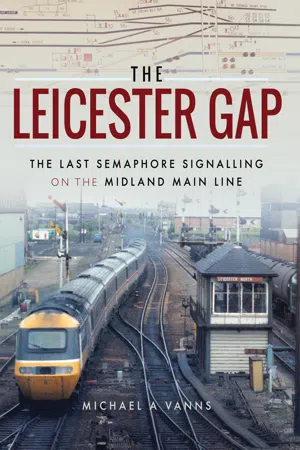

3. Travelling in opposite directions, two HSTs pass each other adjacent to Leicester North signalbox on Wednesday, 28 May 1986. On the left is a Nottingham bound service accelerating northwards away from the camera on the down main line, whilst on the right a London, St Pancras service approaches on the up main line, slowing for its stop in Leicester station’s platform three. This is a very obvious example of ‘separation by direction’, with neither train travelling ‘wrong line’.

The principle of ‘separation by direction’ dated back to 1830 when the Liverpool & Manchester Railway had opened as a double track main line. At this time the electric telegraph was still in its embryonic stage and so there was no way to know where trains were once they had passed out of sight of stations on the route. It was sensible, therefore, given the anticipated amount of traffic to be worked between the two places, to minimise the possibility of collisions, by having two parallel lines dedicated to train movements in only one direction. Collisions between trains when moving in the same direction were likely to be less severe than head on impacts. When the electric telegraph became a practical means of communication in the following decade, there were advocates such as William Fothergill Cooke who argued that single track railways on which trains travelled in either direction could be efficiently and safely controlled by using the electric telegraph and special instruments. By then, however, the principle of ‘separation by direction’ had become the accepted configuration for all main lines. Inevitably, as this became the standard arrangement and as more lines were built and a national railway network began to emerge, all companies agreed that in the normal course of events, trains always ‘ran forward’ on the left-hand line, with trains ‘approaching’ on the opposite, ie right-hand set of tracks. The few exceptions there had been in the 1830s and 40s, had all been eliminated by the end of the 1850s.

As ‘separation by direction’ and ‘left-hand travel’ became established as the fundamental arrangements of double track main lines, ever more comprehensive rules and regulations were formulated based on ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ directions of travel. If a north-bound train was travelling on the track designated for the use of south-bound trains, then it was ‘wrong road’. If unexpected, or unannounced, then that train was to be treated by any railway staff that witnessed it as a run-away. If, however, there was a legitimate reason for a train to travel in the ‘wrong’ direction, then special permission accompanied by special paperwork had to be obtained. Generations of stationmasters, signalmen, train crew and engineering staff, became well acquainted with the completion of ‘Wrong Line Order Forms’ during track maintenance or renewal, or when trains had to be manoeuvred around accidents.

QUADRUPLE TRACK

By the start of the 1860s, traffic carried between towns, cities, ports, collieries, ironworks and all manner of business that were taking advantage of direct rail connections, had increased enormously over the previous three decades. That combined with the growing difference in speed between passenger and goods trains was proving a serious challenge to railway managers. As the passenger trains got faster, goods trains, particularly coal trains, did not and, consequently, line capacity was being compromised. In the 1850s, the electric telegraph had given birth to the ‘block system’ (see Chapter 4) but it was still in its development stage and viewed with suspicion by many senior railway officers. Many considered it restricted train movements unnecessarily. Therefore, when they were faced with the best ways to increase the capacity of their main lines – an apparent choice between more effective signalling systems and laying extra track, they tended to choose the latter.

At first extra track on which goods trains could be separated from passenger trains was provided in the form of lay-by sidings. Although these sidings were laid parallel to the double track, access to them was never direct, trains always having to reverse into them through what were termed ‘trailing points’. [4] This configuration came about because of a general fear that the blades of ‘facing points’ – ie those that would allow direct access between lines, could not be relied upon to close properly, or remain closed, and a train could become derailed so blocking both main line and lay-by siding. Despite the introduction of effective facing point locks by the 1870s, the distrust of facing points lasted until the end of the century. In 1874 James Allport, General Manager of the MR said he ‘…would never have a facing point into a siding if it could possibly be avoided’. But lay-by sidings with trailing points involved risks of their own. Not only did the manoeuvre of reversing long goods trains into them take time, it could also precipitate serious accidents as was proved in the destructive one at Abbotts Ripton on the GNR main line in January 1876 when an express hit a goods train reversing into the lay-by siding there. Almost exactly two years later a similar accident happened at Loughborough when the wagon of a goods train reversing from the down main to the down siding became derailed, the approaching passenger train having insufficient braking power to stop in time to avoid hitting the stranded goods train.

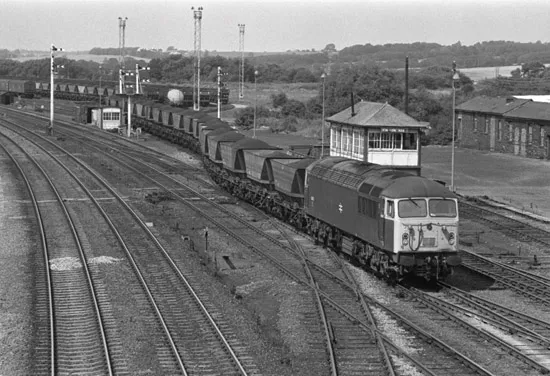

4. At 14.50 on Thursday. 6 August 1987, 56 012 was photographed reversing its MGR coal train from Toton to Blue Circle Industries Ltd’s cement works at Northfleet, Kent (7O85) into the up sidings at Finedon Road, Wellingborough through the trailing points in the up goods line at that location. This manoeuvre was a legacy of the early days of railways in the 1840s and ‘50s when there was a justified fear of trains running through ‘facing points’ directly into sidings. In those decades it was not always possible to guarantee the blades of facing points would remain in the correct position when a train approached nor that they might not open as the train passed over, derailment, therefore, being the inevitable result. The Board of Trade remained very reluctant to sanction facing point connections between lines and its influence was reflected in this layout at Finedon Road, hardly changed in 100 years.

Consequently, lay-by sidings were not the most efficient way to increase line capacity. The best solution for main line companies such as the GNR and MR, proved to be the laying of completely separate and long sections of track adjacent to their existing route for the exclusive use of goods trains. The GNR treated the various sections of additional lines it created between London and just south of Grantham almost as extended lay-by sidings, although accessed via facing points, and they formed loops either side of the existing double track. South of Trent Junction (between Nottingham and Derby) the MR, however, chose to create a new and separate double track route (most of it parallel to the original main line). In the ‘Leicester Gap’ area it started work on this ‘widening’ of its main line in the early 1870s, completing it north of Leicester station to Loughborough (and northwards to Ratcliffe-on-Soar) by February 1875, between Irchester South Junction and Glendon North Junction by May 1884, the final section which included heavy civil engineering work immediately south of Leicester station and a second tunnel a mile further south under Freemans Common completed between July 1890 and October 1893. [5 & 6] By the start of the twentieth century the MR had continuous quadruple track for 75 miles between London and Glendon North Junction, 3 miles north of Kettering station, and then a further 24 miles from Wigston North Junction, 3 miles south of the Leicester station, to Trent Junction and then onwards along the Erewash valley 27 miles to Tapton Junction just north of Chesterfield.

This impressive mileage of continuous quadruple track was not matched by any other pre-Grouping railway company, and the MR, LMS and even British Railways after nationalisation in 1948, used this fact for publicity purposes, often supplying, for use in popular books on railways, photographs of the four parallel lines disappearing into the distance to celebrate this unique British achievement!

5. An unidentified class 50 hauling a train of empty coal hoppers (HAA) out of the sidings and onto the down goods line at Neilsons Sidings, Wellingborough on Monday, 12 May 1986. On the left is the up goods line (occupied in the background by a train of loaded HAAs slowly approaching Finedon Road), and on the right the up and down main lines. These lines formed part of the MR’s Wigston North Junction to Hitchin main line (extension) opened for goods on 4 May 1857 and for passengers four days later, whereas the goods lines here were brought into use in May 1879.

6. The two tunnels beneath Freemans Common, Leicester photographed on a wintery Sunday, 9 February 1986. Furthest from the camera are the up and down passenger lines on their original 1840 alignment as part of the Midland Counties Railway’s (MCR) extension from Trent Junction (between Nottingham and Derby) to Rugby on the London & Birmingham Railway (L&BR), opened throughout to passengers on 30 June that year. The tunnel portal, however, dated from the 1890s when the second bore was being driven to accommodate new up and down goods lines seen here on the left. The new tunnel was brought into use on 22 October 1893 and was rendered redundant on 1 June 1986. (author’s collection)

FACING POINTS AND JUNCTIONS

For operational purposes there had to be many connections between these double track sections at strategic locations and these were invariably arranged as double track junctions. The reason for the junction configuration us...