This is a test

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

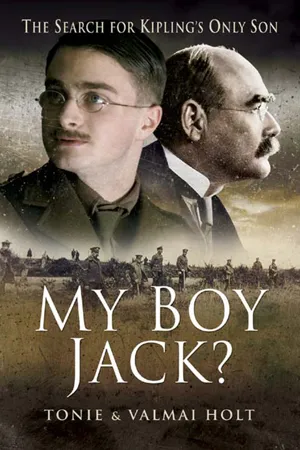

A full account of the tragic life of John "Jack" Kipling, son of Rudyard Kipling, lost in battle during World War I. On September 27, 1915, John Kipling, the only son of Britain's best loved poet, disappeared during the Battle of Loos. His body lay undiscovered for 77 years. Then, in a most unusual move, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) re-marked the grave of an unknown Lieutenant of the Irish Guards, as that of John Kipling. There is considerable evidence that John's grave has been wrongly identified and for the first time in this book, the authors' name the soldier they believe is buried in "John's grave." This is the first biography of John's short life, analyzing the devastating effect it had on his famous father's work.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access My Boy Jack? by Tonie Holt, Valmai Holt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

RUDYARD’S CHILDHOOD:

India. The House of Desolation.

Westward Ho! and Stalky.

‘Give me the first six years of a child’s life and you can have the rest.’

A quotation generally attributed to the Jesuits, reinforced in principal by Diderot, Montaigne and Bernard Shaw, and quoted by Kipling as the heading to Chapter 1 of Something of Myself.

The first five years of Joseph Rudyard Kipling’s life were so happy and satisfyingly secure that they bolstered him through the misery and cruelty of the next six and gave him the outward confidence, sometimes interpreted as ‘cockiness’, that saw him through the rest of his eventful and often tragic life.

He was born on 30 December 1865 in Bombay to John Lockwood Kipling, a short (5’3”), pleasant, intelligent craftsman and artist from a stolid Yorkshire family and his wife Alice. Alice was born to the brilliant and talented Macdonald family. Three of her sisters wed outstanding achievers in their field: Georgiana married the pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones (later to be knighted); Agnes married the artist Edward Poynter (also to be knighted) and Louisa married the MP Alfred Baldwin and gave birth to the future Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin. Alice, too, was intelligent, but her wit and charm were occasionally barbed.

The story goes that they had become engaged after a picnic at Lake Rudyard, now a reservoir near Leek in Staffordshire, and romantically named their first-born son after this spot of sentimental memory to them. The Kipling family tradition was to alternate the names Joseph and John, and Joseph was Rudyard’s first given name. It was the name, in its other form Yussuf, that he would use as one of his many pseudonyms. Lockwood and Alice’s second son, born in 1870, who suffered the fate of so many Anglo-Indian children and lived only long enough to be christened, was called John. Following the pattern, Rudyard was to name his only son John. A daughter, christened Alice like her mother, but always known as ‘Trix’, had been born on 11 June 1868.

Ruddy, as he was affectionately called, was brought up, as was the custom, by an ayah who taught him Hindustani as his first language and fed him on stories of native myth and legend. He had been told that his mother’s difficult labour when giving birth to him had been relieved by making a sacrifice of a kid to the cruel godess Kali. Thus to Kali he owed his existence and, perhaps, his continued compliance to dominant women (his mother, ‘Antirosa’ his child minder in The House of Desolation and later his wife, Carrie.) A small tyrant in this enclosed and comforting kingdom, with occasional interludes with his delightful parents, young Ruddy’s cup of happiness was overbrimming.

When Ruddy was five and a half and Trix was three and a half their parents, in keeping with the traditions of expatriate families, took their children to England for schooling, but the way in which they did it was extraordinary. The practice of sending one’s children home was widespread and considered not only normal but essential for the child’s very survival: infant mortality was frighteningly high in the Anglo-Indian community in the heat and disease of India. What is more, the Kiplings, who were obviously loving parents in the arm’s length fashion of their age and class, had already experienced the death of one child. What was abnormal was their lack of preparation and explanation to the two little children of what was happening to them, and why. Initially it was left to his ayah to tell Rudyard that he was going away. For this information we have to rely on the short story Baa Baa, Black Sheep, a truly terrible account of the mental and physical torture of those nightmare years. This harrowing story, with the first chapter of Something of Myself and the opening chapter of the story The Light that Failed, paint a picture of unbearable childhood misery. Much literary debate has taken place over the accuracy of these three word pictures. The verity of some details is irrelevant: the experience scarred the child and forever influenced the adult creative artist and future father.

It happened when, as Kipling related in Baa Baa, Black Sheep, the children, called Punch and Judy, were roused by their parents ‘in the chill dawn of a February morning [actually it was in December] to say Goodbye’, and then they were gone. No word of for how long, or how necessary it was, simply ‘Don’t forget us ... Oh, my little son, don’t forget us, and see that Judy remembers too.’ Trix later wrote, ‘We had no preparation or explanation; it was like a double death or rather, like an avalanche that had swept away everything happy and familiar ... We felt that we had been deserted, almost as much as on a doorstep, and what was the reason?’

No East-end London child, evacuated to the country in deepest Dorset in 1940 to escape the German bombers, could have felt more alienated. From being the bossy little Sahib, master of his own small kingdom of warmth and light and a myriad of sensual pleasures, Ruddy was projected into the abyss of the cold, dark ‘House of Desolation’, as he called it, where food was so sparse that servants were forced to steal and where he was bullied and beaten. The actual hardships in Lorne Lodge, Southsea, at the hands of Mr and Mrs Holloway (known as ‘Uncleharri’ and ‘Antirosa’ or ‘the Woman’ in Baa Baa, Black Sheep) and their malevolent son, Harry (called the Devil-Boy), are well documented in Rudyard’s writings: the attempt to alienate his only ally, Trix, the accusations of lying, of ‘showing off’, of being ‘the black sheep’ of his family (hence the title of the story), the solitary confinements in his room or in the dank basement, the beatings, and, worst of all, being forbidden to read the books that were his only salvation and escape. Antirosa’s Calvinist religiosity did, however, give Rudyard a knowledge of the Bible that was to stand him in comforting stead throughout the bad times of his life, and even influence his style. The Book of Ecclesiasticus, in particular, provided him with reassuring and resonant phrases that he would use, some 40 years later, in his capacity as a Commissioner of the Imperial War Graves Commission.

The most relevant outcome of Rudyard’s stay at Lorne Lodge to the story of John Kipling is that the received pattern of abused child becoming a child abuser simply did not occur in the case of Rudyard Kipling. One of the mitigating factors was obviously his first stable five years. Then it must be acknowledged that most abuse of children occurs in deprived and uneducated households, neither of which conditions strictly prevailed in ,Lorne Lodge. To read Rudyard’s accounts, the Lorne Lodge household was, however, spartan, (although Rudyard admits to being ‘adequately fed’) and there is no doubt that he was mistreated there. Trix confirmed and even reinforced many of Rudyard’s claims to Birkenhead when he was researching for his Kipling biography in the 1940s. Antirosa ‘drank wine’; she had ‘the power to beat him with many stripes’; according to Baa Baa, Black Sheep, in which it is often impossible to distinguish fact from fiction, she went on holiday with her son Harry and young ‘judy’ (Uncleharri, Ruddy’s only ally, having died) leaving him alone in the house for a month with a servant girl who ‘had many friends’ and ‘went out daily for long hours’; she tied a placard with the word ‘Liar’ on his back and forced him to wear it to school; she threatened him with ‘all the blinding horrors of Hell’; she segregated him from his sister, his only link with home, and failed to notice that he was nearly blind. Thankfully, though distanced from his loving parents, Rudyard was in regular contact with his mother’s family during his years at Lorne Lodge. ‘For a month each year I possessed a paradise which I verily believe saved me,’ he wrote in Something of Myself.

This haven was ‘The Grange’, at North End Road in Hammersmith, home of his mother’s sister, Georgiana and her husband, Edward Burne-Jones. ‘At “The Grange” I had love and affection as much as the greediest, and I was not very greedy, could desire,’ wrote Rudyard. ‘Best of all, immeasurably, was the beloved Aunt herself reading us The Pirate or The Arabian Nights of evenings ... Often the Uncle, who had a “golden voice”, would assist in our evening play.’ He also had the company of his lively cousins Margaret and Philip Burne-Jones and their friends May and Jenny, the daughters of William Morris (known as ‘Uncle Topsy’). This meeting place for the Pre-Raphaelite painters and members of the Arts and Crafts Movement was an intellectually stimulating environment for the knowledge-thirsty young Ruddy. He adored ‘the beloved Aunt’, the feisty Georgie, for the rest of her life.

In Three Houses, 1931, Margaret’s daughter, who was to become the famous novelist Angela Thirkell, described her grandparents, and the ‘open house’ that they kept for friends and relatives every Sunday at ‘The Grange’. ‘There can be few granddaughters who were so systematically spoiled as I was,’ she wrote. That affection was also shown to their virtually orphaned nephew and niece from far-off India. One wonders how they did not sense Rudyard’s unhappiness. ‘Often and often afterwards, the beloved Aunt would ask me why I had never told anyone how I was being treated. Children tell little more than animals, for what comes to them they accept as eternally established,’ Rudyard explained in Something of Myself. But eventually, when ‘some sort of nervous breakdown’ occurred, Georgie must have been informed, for she sent for ‘Inverarity Sahib’, the doctor who had delivered Rudyard as a baby in India and who would now deliver him from Antirosa.

‘Good God, the little chap’s nearly blind!’ he exclaimed. It was a momentous revelation. Rudyard’s ‘lovely Mamma’ was summoned, arrived unexpectedly to the bewildered Rudyard (‘1 do not remember that 1had any warning’), bathed him in kisses and tears of guilt and remorse and took the children away from the House of Desolation.

Spectacles were quickly prescribed for the neglected eyesight and so began one of Rudyard’s lifelong fears: that he would become blind. The poor eyesight was another link that was to bind him to his son John, who also had deficient eyesight and had to wear spectacles. As we shall see this was a significant factor in John’s premature death.

That he was physically able to read again, and do so without any restraint, was a key to Rudyard remembering the next few months as among the most enjoyable in his life. They started in the relaxed environment of a farmhouse at Loughton near Epping Forest, joined occasionally by their cousin Stanley Baldwin, sealing a lifelong friendship. There ‘I was completely happy with my Mother,’ he wrote in Something of Myself. No wonder: any display of love and kindness must have seemed like heaven to the two deprived children. But, despite Alice’s efforts to reingratiate herself with her son, it was his father to whom Ruddy would feel closer in later years.

The next important episode in Rudyard’s life, and one which was later to affect his attitude as a father with a son at public school, was the period of his own schooldays at the United Services College at Westward Ho! It was an experience that gave him the material for the series of short stories that were later collected under the name Stalky & Co.

The establishment was designed to produce officer material for the British Army or the upper echelons of the Civil Service. Rudyard was never destined for either. The choice of school was made purely on its cheapness and the strength of the family’s friendship with the nonconformist Headmaster, Cormell Price, who had taught at Haileybury, after which establishment he, to a certain extent, modelled Westward Ho! At Oxford Price had been a member of the pre-Raphaelite/Arts and Crafts set, but he veered away from them, first to study medicine and then to become a tutor in Russia. He was an exceptional man who early recognized the potential of his nonconformist pupil. In later conversations ‘Uncle Crom’ revealed to Kipling how he had deliberately tested and stretched him and encouraged other masters to do likewise. During his final weeks at the school, as Kipling recounts in the Stalky & Co story The Last Term, and in Something of Myself, he was given the run of the Head’s personal Library Study as editor of the school magazine, The United Services College Chronicle. ‘Many of us loved the Head for what he had done for us, but I owed him more than all of them put together and I think I loved him even more than they did,’ he recorded. Cormell Price was to remain a well-loved mentor until his death in 1910.

Though credit must be given to Price for nurturing the fish-out-of-water child, it must also devolve on Rudyard for not only surviving, but triumphing in his own way in what was for him a hostile environment. Kipling was bookish (a ‘swot’) and hopeless at sport (with the exception of swimming) in a society where sporting achievement was revered. He came from an artistic, rather than a military background. He was oddlooking where physical beauty was admired: he was small- full-grown he would reach no more than 5’6” - hirsute, had to start shaving at an early age, sported a moustache by the age of 15, had thick dark eyebrows, and above all he had to wear glasses - the only boy in the school to do so. It led to his nickname of ‘Gigger’, for gig (carriage) lamps, which was a term he would use himself for glasses in later years. Yet he was popular with his peers and his friendship with the originals of the main characters of the Stalky saga, Lionel Charles Dunsterville (Stalky) and George C. Beresford (M’Turk), was to remain steadfast throughout all their lives.

The main lessons that Rudyard learned at USC that he would endeavour to pass on to his own son can be summed up in the code of Kim. One should be manly at all times, calm in adversity, and survive, and be strengthened by, the testing and character-building situations that life meted out. One should also guard against ‘beastliness’ - Kipling’s euphemism for juvenile homosexuality. In the light of the suggestion of his own homosexual feelings (in particular in regard to his brother-in-law Wolcott Balestier), Rudyard may have protested a little too much about the ‘cleanliness’ of Westward Ho! ‘I remember no cases of even suspected perversion,’ he wrote in Something of Myself, and even discussed this rare absence of homosexuality in the Public School of the age with Cormell Price after he left school. Price’s antidote was to send the boys to bed ‘dead tired.’ That it did exist in the school might be indicated by a claim made by M’Turk in Slaves of the Lamp, 1, that ‘The Head never expels except for beastliness or stealing.’ As described by Seymour-Smith, Kipling had also been moved during his last term, by his housemaster, M.H. Pugh, from the dormitory he shared with Beresford. Pugh (who appears as ‘Prout’ in the Stalky saga) obviously suspected ‘impurity and bestiality’, indicating that homosexuality did exist in the school.

Kipling also urged John to endeavour to become a prefect. It was a position that, in part because Rudyard left school early and also because ‘in large part to their House-master’s experienced distrust, the three [Stalky, M’Turk, and Beetle, one of Kipling’s own nicknames at school because of his hunched and dark appearance] for three consecutive terms had been passed over for promotion to the rank of prefect’, Rudyard would never attain himself. It was another example of him wishing to achieve through his son. ‘I want you to be a pre before I die,’ he wrote on 24 May 1913. ‘I think with your knowledge of mixed human nature you’d make a good ~. I never was one.’ Ironically he also warned John not to try ‘scoring off a beak. He may stand it a dozen times but sooner or later you’ll hit on a time when his liver is annoying him or he is otherwise short in the temper and then you’ll have to pay...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Additional Info

- By the Same Authors

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements and Sources

- My Boy Jack (Poem)

- Introduction

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Epilogue

- Postscript to 2001 Edition

- What the Experts Said

- Select Bibliography

- Appendix to 2007 Edition