![]()

— 1 —

Introduction

THIS BOOK DOCUMENTS THE German invasion of Norway in April 1940 (Operation Weserübung), focusing on the events at sea.1 The objective is to give a balanced and factual account; readable but without compromising the demand for research and accurate detail.

As far as possible, the narrative has been based on primary sources. There is still an overwhelming amount of detail and anybody having information that would lead to modifications or improvements are more than welcome to contact me. The research material has come in many languages: Norwegian, German, English, Swedish, Danish and French. All translations into English are my own responsibility and where necessary I have striven to maintain the significance of what was said or written rather than create a word-by-word translation.

The military impact of Operation Weserübung has largely been overshadowed by the events on the Western Front and the fall of France, but there is no doubt that the invasion of Norway and the subsequent campaign had a significant influence on WWII in Europe. On paper, Germany had made a move of great strategic significance, breaking the British blockade of the North Sea and opening a potential to strike out towards the Atlantic. Lacking the resources to capitalise on the gains though, the conquest instead became a burden. The surface arm of the German Navy was small before the operation; afterwards it was crippled virtually beyond recovery. There were insufficient resources available to develop the full potential of the Norwegian bases and through the loss of many large surface ships the Kriegsmarine was, in reality, converted to a navy of small ships, incapable of even considering reaping any strategic gains from the venture. The Norwegian U-boat bases were of limited value compared to those on the French coast that became available very shortly after the Norwegian ones.

Nevertheless, Hitler and his senior staff were strengthened by Operation Weserübung and in spite of grave losses, the Führer consolidated his grip on the armed forces, paving the way for the campaigns in the West and in Russia.

The true strategic value of Norwegian territory appeared after the invasion of Russia in 1941, when northern Norway was used as a springboard for the polar front and the air and naval attacks on the supply route to Murmansk – neither of which were considered at all in 1940. Even after the attack on Russia it was difficult for the German Navy to find the resources to utilise the Norwegian ports and seaways to their full potential.

The loss of Norway and her territorial waters was in itself not catastrophic for the Allies but it took away an option to outflank Germany at the start of the campaign in France. Ironically, the most persuasive asset for either side prior to the events, the Swedish iron ore, was almost irrelevant afterwards. The supply to Germany continued virtually unaffected through the Baltic, and its strategic value diminished as the iron-ore mines in Lorraine were seized shortly after.

![]()

— 2 —

Wheels Within Wheels

Operation Weserübung

THERE WERE NO GERMAN plans whatsoever for an attack on Scandinavia in September 1939. The rationale for Hitler to unleash his dogs of war on Norway and Denmark seven months later developed during the winter through a series of intertwined incidents and processes involving the German fear of being outflanked, Norwegian neutrality policy, and Allied aspirations to sever German iron-ore supplies and to establish an alternative front in Scandinavia.

The first of several catalysts for the development was a visit to Berlin by the Norwegian National Socialist leader Vidkun Quisling in December 1939. He arrived on the 10th to keep abreast of political issues and to try to activate German support for his minority party. Instead, he was willingly entangled in an impromptu plan – the consequences of which were out of all proportion – staged by Quisling’s man in Germany, Albert Hagelin.1 The morning after his arrival, Quisling was taken by Hagelin to see Reichsleiter Alfred Rosenberg, head of the Nazi Party’s internal ‘Foreign Policy Office and Propaganda Section’.2 The two men, who had met before, discussed the situation in Norway, which Quisling held had become very anti-German after the alliance with Russia and that country’s attack on Finland.

Hagelin was also friendly with Fregattenkapitän Erich Schulte-Mönting, the navy Chief of Staff, and in the afternoon Quisling was brought to the naval headquarters at Tirpizufer. Here, Schulte-Mönting introduced the Norwegians to Grossadmiral Erich Raeder, the C-in-C of the German Navy. Quisling presented himself (correctly) as an ex-major who had served in the Norwegian General Staff and as a former defence minister. Raeder was impressed and gave him his attention, all the more so because Hagelin (falsely) managed to give the impression that Quisling was the leader of a significant political party with strong military and ministerial connections. Raeder had for some time argued in favour of an expansion of the Kriegsmarine’s operating base into Scandinavia and saw an opportunity for support.3 At the Führer conference on 12 December, the admiral recounted his conversation with the Norwegian, referring to Quisling as ‘well informed and giving a trustworthy impression’. He also took the opportunity to recount the threat that a British landing in Norway – which Quisling held to be very likely – would create for the iron-ore traffic and the Kriegsmarine’s ability to maintain an effective merchant war against England. Cautioning that the Norwegian might be playing a political game of his own, he nevertheless recommended that Hitler meet him and make up his own mind. Raeder suggested that if the Führer was left with a positive impression, the High Command of the armed forces (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht – OKW) should be allowed to work out provisional plans for an occupation of Norway, peacefully or with force. Hitler consulted with Rosenberg, who recommended Quisling highly, and invited the Norwegian to the Reichskanzlei on 13 December.4

Admiral Erich Raeder (right) at the launch of the cruiser Admiral Hipper in February 1937. (Author’s collection)

Quisling came accompanied by Hagelin and Rosenberg’s subordinate, Amtsleiter Hans-Wilhelm Scheidt, head of the Nordic Office.5 Scheidt later wrote that Hitler listened ‘quietly and attentively’ to Quisling, who spoke thoughtfully in halting German.6 The general Norwegian attitude had been firmly pro-British for a long time, Quisling said, and in his opinion it was ‘obvious that England did not intend to respect Norwegian neutrality’. The president of the Parliament, Stortingspresident Carl Hambro, was of Jewish descent and Quisling asserted he had close connections to the British secretary of state, Leslie Hore-Belisha, also Jewish.7 These two, he claimed, conspired to bring Norway into the war on the Allied side and to secure British bases in Norway. Indeed, there was evidence that the Norwegian government had already secretly agreed to Allied occupation of parts of southern Norway, from which Germany’s northern flank could be threatened. Concluding, Quisling asserted that his party, the Nasjonal Samling (NS), had a large and growing group of followers, many of whom were in key positions in the civil administration and the armed forces. With the support of these people, he would be prepared to intervene through a coup to avert ‘Hambro’s British plans’ and, having seized power, to ‘invite German troops to take possession of key positions along the coast’.8

Hitler then delivered a twenty-minute monologue underlining that Germany had no plans for an intervention in Norway while its neutrality was properly enforced. He had always been a friend of England, he held, and was bitter about the declaration of war over Poland. He now hoped to force England to her knees through a blockade rather than full-scale war. A British occupation of Norway would be totally unacceptable and, according to Scheidt, Hitler made it clear that ‘Any sign of English intervention in Norway would be met with appropriate means.’ It would be preferable to use the troops elsewhere, but ‘Should the danger of a British violation of Norwegian neutrality ever become acute …, he would land in Norway with six, eight, twelve divisions, and even more if necessary.’ Quisling wrote that ‘Upon mentioning the eventuality of a violation of [Norwegian] neutrality, Hitler worked himself into a frenzy.’

When Quisling had left, Generalmajor Alfred Jodl, chief of the operations office at OKW, was instructed to start a low-key investigation ‘with the smallest of staffs’ into how Norway could be occupied ‘should it become necessary’. Several meetings were held over the next few days regarding Norway. Quisling, Hagelin and Scheidt participated in some and apparently received repeated promise of support. Unprecedentedly, Quisling was invited back to the Reichskanzlei on the 18th. This time, Hitler was virtually the only one to speak. He restated his absolute preference for a neutral Norway, but stressed that unless the neutrality was strictly enforced, he would be required to take appropriate measures, securing German interests. British landings in Norway were totally unacceptable and would have to be pre-empted. Finally, Hitler underlined the confidentiality of their meetings but indicated that Quisling would be consulted should a pre-emptive intervention become necessary. There was no mention of any plans for a coup.9

Quisling’s skewed description of the situation in Norway was at best a product of his imagination, but his assessment of the alleged political situation in Norway made an impression in the Reichskanzlei. Hitler was already frustrated by the growing anti-German sentiment in Scandinavia, and the Norwegian’s account of a Jewish-influenced Anglo-Norwegian alliance conspiring for offensive operations made sense to him; it was far from reality, but it had the right ingredients. Used by internal German forces protecting their own interests, Quisling had authenticated previous warnings of Allied intentions in Scandinavia and events were about to take a new direction.10

Neither the German Embassy in Oslo nor the Foreign Office in Berlin had been involved in Quisling’s visit to Germany and when Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop learned that Quisling had met with Hitler he became rather disturbed. The German minister in Oslo, Curt Bräuer, confirmed that Quisling had exaggerated his leverage in Norway and vastly overstated the number of his followers and their political and military influence. Bräuer affirmed that Quisling’s sympathies were national-socialistic and pro-German enough, but his politics could not be taken seriously. In Bräuer’s opinion, openly siding with Quisling and his party would at best be a waste of resources and could very well harm German interests. ‘Nasjonal Samling has no influence in this country and probably never will,’ he concluded, adding that there were no indications that Quisling had support among Norwegian officers. As far as could be judged by the embassy, the officers were loyal to the government, which was really making an effort to enforce the country’s neutrality. The OKW frowned on the prospect of an operation that would depend on support from Norwegian confidants – not to mention the difficulties of maintaining security.11 ‘Quisling has no one behind him,’ army Chief of Staff Generaloberst Halder remarked laconically in his diary. Hitler listened for once and it was decided that even if Scheidt went to Oslo, he should keep the Norwegian ‘Führer’ at arm’s length and, above all, not involve him in any planning.12

Hence, Quisling would have no further involvement in the ensuing preparations for the invasion of Norway, although he took all he had been promised at face value and went home, trusting plans were being developed in Germany that would eventually put him in power in Norway. It is doubtful if Quisling realised he had been sidelined, and that neither he nor his coup figured in the German plans. He stood alone in his treachery and nobody except Hagelin was fully involved.13

After attending a Führer conference on 1 January 1940, Halder wrote in his diary: ‘It is in our interest that Norway remains neutral. We must be prepared to change our view on this, however, should England threaten Norway’s neutrality. The Führer has instructed Jodl to have a report made on the issue.’14 The plan for an intervention in Scandinavia was but a contingency at this stage, only to be activated against a clear British threat. As no such threat was substantiated, focus remained in the West, but wheels had been set in motion.

The initial sketch of the plan, ‘Studie Nord’, was completed by OKW during the second week of January. The Luftwaffe and army staffs were preoccupied with the attack on France and showed little interest when asked to comment. Raeder, on the other hand, ordered the Naval High Command (Seekriegsleitung – SKL), to assess Studie Nord properly and prepare constructive feedback. This they did, concluding that continued Norwegian neutrality was to the advantage of Germany and a British presence could not be tolerated. Still, pre-emptive plans would have to be developed – just in case. On 27 January, Hitler instructed the OKW to set up a special staff – Sonderstab Weserübung – to develop plans for such an operation. Kapitän zur See Theodor Krancke was given the task of leading the work, which commenced on 5 February, based largely on an updated version of SKL’s comments and feedback to Studie Nord.15 Knowledge of Weserübung was to be restricted and the ‘issue of Norway should not leave the hands of the OKW’. Two basic principles emerged when the Sonderstab set down to work. First, an occupation of bases in southern Norway alone was pointless and would be difficult to uphold; Trondheim and Narvik would have to be occupied, as well as the sea lanes along the coast, to secure the transport of iron ore. Secondly, occupation of at least parts of Denmark would be necessary in order to secure sustainable connections to Norway across the Skagerrak and to prevent Allied access to the Baltic. Air bases in northern Jylland would also facilitate anti-shipping operations and reconnaissance in the North Sea.16

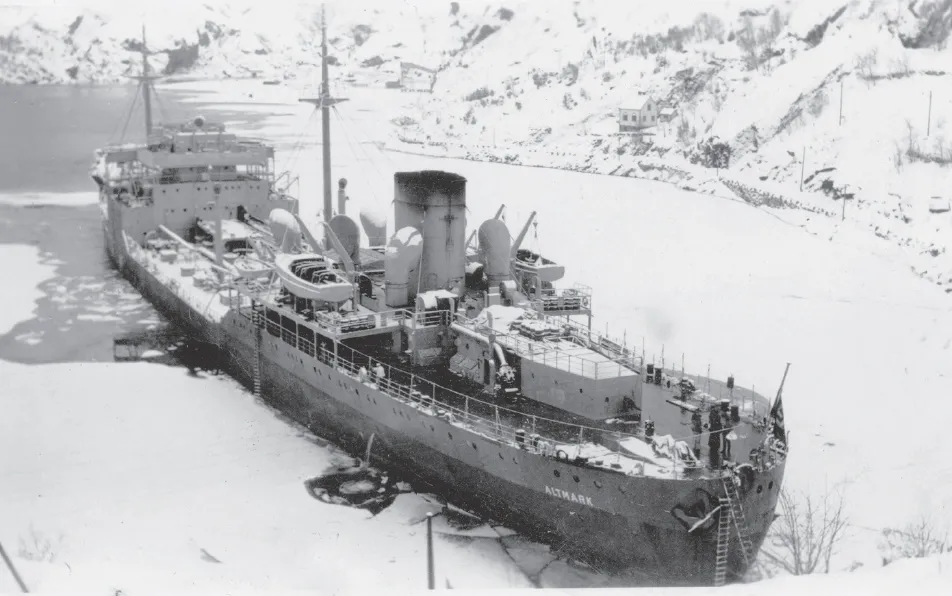

Shortly before midnight on 16 February 1940, Captain Philip Vian, on Churchill’s orders, took the British destroyer Cossack into Norwegian territorial waters at Jøssingfjord, south of Stavanger. In spite of protests from Norwegian naval vessels, he attacked and boarded the German tanker Altmark. During the ensuing skirmish, 299 British sailors captured in the South Atlantic by the raider Admiral Graf Spee were liberated from Altmark while eight German sailors were killed. This was at the height of the ‘phoney war’ and the incident created headlines all over the world. General Jodl wrote in his diary that Hitler was furious about the lack of opposition from Germans and Norwegians alike: ‘No opposition, no British losses!’ The Royal Navy had humiliated Germany and the Norwegians had been unable – or unwilling – to defend their neutrality against the British intruders. Rosenberg wrote: ‘Downright stupid of Churchill. This confirms Quisling was right. I saw the Führer today and … there is nothing left of his determination to preserve Nordic neutrality.’

Commissioned in 1938, the 10,698-GRT Altmark belonged to a class of fleet auxiliaries, an integral part of the Kriegsmarine’s merchant warfare. On her way home from the South Atlantic, where she had supported the Graf Spee, she was driven into Jøssingfjord south of Stavanger by British destroyers in the afternoon of 16 February 1940. During the night, Captain(D) Philip Vian of the 4th Destroyer Flotilla took Cossack into the fjord in spite of Norwegian protests and after a short gunfight liberated 299 British sailors, captured by Graf Spee. Eight German sailors were killed. (Author’s collection)

The day after the boarding of Altmark, Admiral Raeder was told by an angry Hitler that as Norway ‘was no longer able to maintain its neutrality’, the planning of Operation Weserübung was to be intensified immediately. The time had come to take control of events rather than just prepare for an eventuality. Raeder, uncomfortable with the sudden hurry, advised caution. In another meeting with Hitler a few days later, he argued that maintaini...