![]()

1

‘A TERRIBLE FEELING OF FALLING’

The New Governor Arrives in Hong Kong

Western writers have been by turns entranced and appalled by their experience of Hong Kong. Ian Fleming, writing in the early sixties, described the city as ‘the last stronghold of feudal luxury in the world . . . a gay and splendid colony humming with vitality and progress, and pure joy to the senses and spirits’. A decade later, John le Carré set a memorable episode of The Honourable Schoolboy in Hong Kong. Describing a taxi ride in bad weather up the winding road from the city centre to the top of the Peak, he wrote that the car ‘sobbed slowly up the concrete cliffs’, which were engulfed by ‘a fog thick enough to choke on’. Outside the taxi, ‘it was even worse. A hot, unbudgeable curtain had spread itself across the summit, reeking of petrol and crammed with the din of the valley. The moisture floated in hot, fine swarms.’ On a clear day it would have been possible to see far out over the harbour across Kowloon towards the New Territories, and beyond a vagueness of mountains that marked the border with the People’s Republic of China.

The Peak has long been de rigueur for tourists, who usually prefer to travel to the top in the Peak Tram which clanks up the sheer side of the mountain. Jan Morris, Hong Kong’s finest apologist, took this route in the seventies, accompanied by a ‘foreign devil’ who showed her the ‘kingdoms of the world’ which lay below them: ‘The skyscrapers of Victoria, jam-packed at the foot of the hill, seemed to vibrate with pride, greed, energy and success, and all among them the traffic swirled, and the crowds milled, and the shops glittered, and the money rang.’ By no means starry-eyed, however, she also saw this throbbing megalopolis as a ‘permanent parasite’ upon the skin of China, wherein the British and the Chinese, springing from ‘two utterly alien cultures, from opposite ends of the world’ are ‘fused in the furnace of Hong Kong, and made colleagues by the hope of profit’.

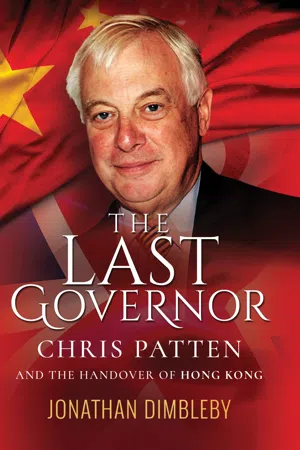

The last governor of Britain’s last colony landed at Kai Tak Airport on 9 July 1992, on schedule at two o’clock in the afternoon. Accompanied by his wife, Lavender, and two of his three daughters, Laura and Alice, Chris Patten stepped off the aircraft to face a battery of television cameras and journalists corralled on the tarmac by officials of the Government Information Services. The weather was routinely sweltering and the humidity nudged towards 100 per cent. Hong Kong’s new first family, the source of much excited chatter in the local media since the announcement of Patten’s appointment, smiled self-consciously and disappeared into the merciful cool of the VIP lounge.

After a pause for refreshments, the Patten motorcade left the airport to drive through the heart of Kowloon to the public pier, where the family boarded the Lady Maurine, the elderly and elegant motor yacht provided by the Hong Kong government for the personal use of the governor and which, along with an equally ancient Rolls-Royce, was one of the gubernatorial perks to provoke in some a titter of envy. Led by a Royal Navy warship and surrounded by a flotilla of naval and police launches and a convoy of pleasure craft, the Patten family made stately progress across the harbour to disembark at Queen’s Pier. A couple of fireboats sprayed a welcoming spume of water as she passed. RAF jets and army helicopters flew low overhead. Foghorns blasted and the sound of a seventeen-gun salute from the naval landbase HMS Tamar ricocheted around the waiting crowd. There was a guard of honour and a Gurkha band played the national anthem. Patten took the salute with his wife and children beside him, their dresses swishing slowly in a sultry breeze. For aficionados it was colonialism encapsulated in a single image – even if their new overlord, surrounded by so much gold braid, did cut an underwhelming figure in a plain grey suit and without the gubernatorial plumed hat favoured by his predecessors.

In the dog days of colonialism it had become customary for the media in London to caricature the motley selection of superannuated politicians dispatched to govern Britain’s dwindling possessions as faintly ridiculous refugees from a Gilbert and Sullivan opera strutting their way into the imperial sunset. Patten had no intention of either joining that twilight galaxy or dressing the part, which was one of the reasons why he had decided to forgo both the plumed hat and the ceremonial uniform. There was also an aesthetic consideration: ‘If you are built like one of those sketches for a Daks suit from Simpson’s, you can get away with wearing a hat – as someone said to me rather indelicately – with a chicken on top and that wonderful white tropical kit. If you are built like me, medium-sized and lumpy, you do look extremely foolish.’ His friends had been disappointed. ‘The prime minister said that I had been a frightful spoilsport. Lots of people who were looking forward to a rather more cheerful breakfast when they looked at photographs of me in the paper were to be denied that pleasure.’ A more pertinent, if no less self-conscious reason for his abstinence lay in his determination to impress upon popular opinion in Hong Kong that in style and character he was cast in a quite different mould from his predecessors; that his governorship would be ‘more open and accessible and without some of the flummery’ which had been traditionally associated with the post.

The power vested in the governor of Hong Kong under the Letters Patent, which gave him absolute executive authority over the colony as the head of government and commander-in-chief of the armed forces, was a sharp reminder to Patten that he lacked the popular legitimacy of an elected leader, and it made him vaguely queasy. With this in mind, he not only resisted the ‘flummery’ of his new office but also turned down the knighthood that traditionally went with it. ‘There were negotiations and the Palace was receptive and helpful,’ he confided. ‘I’ve got my house colours as a privy councillor, which, for a politician, is the most important honour you can have . . . I think the time for an additional honour, if there does come a time, should be when I’ve actually done something for Hong Kong, not just because I’ve taken a job.’

The welcome he was given was friendly but not effusive. Foreign tourists and expatriates, as intrigued by the Patten daughters as by the new governor himself, all but outnumbered the local population. The people of Hong Kong had seen too many British officials alight on their soil to be anything other than sceptical about the latest arrival. However, even the sceptics acknowledged that Patten was a little different. For weeks the local media had regaled their public with every recycled titbit about the new governor and his family: how Lavender had been a barrister in London; that their eldest daughter Kate was in South America before starting a degree course at Newcastle University; that Laura, a photogenic seventeen and given to stylishly short dresses, would stay for a while but might return to work in London; and that twelve-year-old Alice would be living at Government House and would become a pupil at the Island School in the Midlevels. Patten himself was a good deal younger than any of his recent predecessors, who had been rewarded with the governorship towards the close of their careers. And unlike his predecessors, he was already a public figure, even – in Britain at least – something of a star. As written up by the assiduous Hong Kong press, the Pattens had all the makings of a genuine first family: politically glamorous and pleasingly enthusiastic about the adventure ahead of them.

It was not merely that Patten exuded bonhomie; nor that he waved from the Rolls and searched for hands to shake with the manic energy of a campaigning politician; nor that his face easily creased in what seemed to be a genuinely eager smile, even if, on the first humid day, his complexion assumed an ever-deepening shade of puce. All that helped, but there was something else: from the start, he exuded a self-confidence and certainty which implied, even via the unyieldingly attentive television cameras recording his arrival, that he had a purpose and he knew what it was. Even the cynical – which included most of those of whatever viewpoint who had taken more than a spasmodic interest in the unfolding drama of the previous decade, and who knew Albion to be perfidious – could not help feeling a frisson of anticipatory excitement. For better, for worse, life with the new governor – Peng Dingkang in the official Cantonese translation, or Fat Pang, as he soon came to be called – at least promised to be far from boring.

Chris Patten had been preceded to Hong Kong by a formidable reputation as one of the Conservative government’s heavyweights. The prime minister’s close friend and most trusted confidant, he was deemed to have snatched electoral victory for his party from what the polls had predicted to be certain defeat. In the process, he became, in his own characteristic phrase, ‘the only Cabinet minister careless enough to lose his seat’ in his own west-country constituency of Bath.

In Britain, Patten had been a skilled political communicator. His way with the English language had earned him a reputation as a thoughtful and fastidious politician who avoided the coarse public dialogue in which so many of his colleagues indulged. His was by no means a high Tory background: his father worked in what was then called Tin Pan Alley (Patten would recall proudly that he published the hit song ‘She Wears Red Feathers and a Hooly-Hooly Skirt’). A scholarship boy, he was educated at Catholic schools and read history at Balliol College, Oxford, where he co-authored the annual college review in which he updated fragments by the Greek writer Aristophanes. Patten evinced no interest in politics until, having won a Coolidge Travelling Scholarship to the United States, he was given a job as a researcher with the team running John Lindsay’s 1965 campaign to become mayor of New York. Enthused by this experience of politics in the raw, he returned to London and eschewed a BBC traineeship to join the Conservative Research Department. After four years he went to the Cabinet Office, and two years later, in 1972, he became private secretary to the party chairman, Peter Carrington. On his return to the research department as director in 1974, he soon fell foul of the new party leader, Margaret Thatcher, who regarded him as deplorably hostile to her radical vision. Although he remained at the research department he was effectively ostracised by Thatcher. As one of his friends told the writer John Newhouse, ‘Chris protested and then went into outer darkness.’

In the 1979 election Patten won the marginal seat of Bath, going on to serve his ministerial apprenticeship as a PPS at Social Services and a parliamentary under-secretary at the Northern Ireland Office before rising to become minister of state, first at the Department of Education and Science and then, between 1986 and 1989, in the Foreign Office, where he was in charge of overseas development. Despite his relatively slow progress, he had already been cast by his peers in all parties in the role of ‘future leader’. Although he was averse to the style of Thatcherism, and semi-detached from much of its content, he had managed to overcome his distaste to the point of toiling annually in the arid vineyard of the prime minister’s speeches to the Conservative Party Conference, attempting to bring eloquence to her thought and life to her prose. His reward, in 1989, was a place in the Cabinet as secretary of state for the environment, charged with ‘bedding down’ Thatcher’s community charge, steered on to the statute book by Nicholas Ridley. Though Patten regarded the poll tax as a catastrophe, the last gasp of a leader who had lost touch with political reality, he did not hesitate to bludgeon the bill’s opponents in the House of Commons – to their amazement and to the dismay of his admirers beyond Westminster, who could not understand how such an apparently decent politician could be party to so manifest an injustice. In failing to appreciate the iron laws of collective responsibility, they also underestimated the careful ambition of a politician which was obscured by a beguiling persona in which high seriousness and dry humour were, in that grey age, refreshingly entwined.

Patten had comforted himself by letting it be known at Westminster that he found the ‘old girl’ faintly ridiculous. In private he was also scathing about the vainglory of lesser colleagues. Contemptuous of romantic argument, whether it emanated from the right or the left, his response to it had been to acquire the disconcerting habit of slowly rolling his eyes in exaggerated bewilderment, as if to indicate that its proponent had to be off his – or, in the case of Thatcher, her – trolley.

Patten’s ‘success’ in imposing the community charge on a resentful populace helped precipitate Thatcher’s downfall. Forced to defend her leadership in a party election, she failed to win outright in the first ballot. Believing her to be mortally wounded, Patten joined the health secretary, Kenneth Clarke, in telling her that it was time to retire gracefully. He warned that if she did not follow their advice, they, like many of their colleagues, would be unable to support her in the second round. She departed for the House of Lords, blessing John Major as her successor in the Commons. Major duly defeated the foreign secretary, Douglas Hurd, and the former defence secretary, Michael Heseltine, to emerge as leader and prime minister.

Patten was appointed chairman of the party to mastermind John Major’s victory over a resurgent Labour party. The 1992 campaign was not an elevated affair. Bending himself to the task of achieving victory, Patten started to deploy terms like ‘double whammy’, ‘gobsmacked’ and ‘porkies’, as if to demonstrate to genuine street-brawlers like Lord Tebbit (a predecessor in the post) that he, too, was an upper-echelon bruiser. Many commentators were genuinely taken aback by his vulgarity, while his opponents affected dismay that such an eminently reasonable politician should stoop to such abuse. Yet those who knew him well were already accustomed to his private, if quaintly anachronistic earthiness, and were surprised only that this trait had not emerged earlier in his career. The Patten they knew was a complex individual, a man of pragmatic conviction, blessed with religious faith, who lived for politics but also had what Denis Healey had memorably called ‘a hinterland’. He had one of the best political brains of his generation among the Tory high-flyers. An ideologue who wore his commitment lightly, he was a Conservative in the mould of ‘Rab’ Butler and Sir Edward Boyle, formal photographs of whom had become part of his office furniture. Yet unlike those icons of ‘one-nation’ Toryism, he was also, in the political sense, more of a thug than his genial demeanour suggested.

Armed with a swift wit and a gift for the apposite phrase, he had long been the leading figure in a group of sympathetic contemporaries which included such luminaries as William Waldegrave, Tristan Garel-Jones, his namesake, John Patten, and John Major, before the latter’s meteoric rise at the behest of Margaret Thatcher. Perhaps not as clever as Waldegrave, nor so artful as Garel-Jones, and less volatile than John Patten, he nonetheless dominated the group with effortless aplomb. To the chagrin of political journalists, even the most ambitious of his colleagues, who were usually swift to deprecate each other in private, stayed their hands. He was the one to whom others turned for advice and reassurance, and whose judgement was trusted, even by his fiercest rivals. Some likened him to Lord Whitelaw, whose benign countenance disguised a shrewd political wisdom on which Margaret Thatcher had learned to rely. But the comparison was inapt: Whitelaw lacked ambition and the ‘killer’ instinct to go with it. Patten wanted to be prime minister, and he was not nearly so squeamish about it as his self-deprecatory manner might have implied. His asperity in argument left none of his friends in any doubt that the master of the emollient soundbite was very much tougher than his image might suggest.

In his final weeks as the Conservative MP for Bath, that political armour was tested to the limit. Patten had been resigned to the prospect of defeat from the start of the election campaign. Damaged by his association with the poll tax, he was also held responsible for the injustices of the uniform business rate – not least in his own constituency, where some traders faced consequential ruin. As party chairman he was obliged to be in London under the daily scrutiny of the media, and although he was ferried to Bath by helicopter, his campaign in what had long been a marginal seat was inevitably spasmodic. In his constituency he became a scapegoat for the government’s unpopularity and, as the canvass returns seemed to confirm, enough of his sophisticated electorate had resolved to vote ‘tactically’ against him to ensure that at least one member of the Cabinet would be driven from office.

The rejection was more painful than he had anticipated. Afterwards he tried to draw comfort from Adlai Stevenson’s reaction after his defeat in the 1952 US presidential elections. Like a small boy who had stubbed his toe, ‘It hurt too much to laugh but I was too grown up to cry.’ Patten resisted the temptation to blame the burghers of Bath, but he was to harbour lasting resentment about the raucous delight with which some of his opponents at the count greeted his defeat. His farewell speech was dignified, decent and generous, but his successor, the Liberal Democrat Don Foster, failed to offer the customary condolences, an omission or oversight which rankled. Reports that some rightwingers at an election gathering in London hosted by the party’s treasurer, Lord McAlpine, had toasted his demise even as they celebrated the victory of which he had been the principal architect did little to soothe his wounded spirits. Exhausted by an election campaign which, as usual, had been demeaned by personal abuse and vilification, Patten left Central Office in the early hours of Friday morning, sustained by the gratitude of a jubilant prime minister but conscious that, for the moment, his own career in British politics was at an end.

Knowing that Patten was unlikely to hold his seat in Bath, the prime minister had held out the promise of the Hong Kong governorship to his friend some weeks earlier. On the day after the election, Major renewed the offer, but at the same time intimated that he would dearly like Patten to reject the Hong Kong option in favour of remaining in his Cabinet. It was common knowledge that the prime minister had come to rely heavily on Patten’s acute political intelligence as well as on his skills as a communicator. Patten exuded that air of relaxed assurance that Major could never master; it would be invaluable to have such a ‘safe pair of hands’ close by to help navigate the government through the turbulent waters of domestic politics that lay ahead. As Patten recalled their conversation a few days later, Major made it clear that ‘he’d have liked me to stay around, but he recognised that Hong Kong was a big job . . . [and that] without being too vain, I sort of fitted the bill . . . I guess quite a lot of my friends, while recognising the importance of the job and flattering me into thinking I could do it, also flatteringly, hoped that I’d stay in London.’

Indeed, within hours of the election some of his closest friends were counselling him to find a ‘safe’ seat (in Chelsea, for instance, former minister and fellow ‘wet’ Nicholas Scott had indicated that he would be ready to stand down in favour of such a formidable successor), or to accept John Major’s offer of a peerage and a place in the Cabinet with the prospect of succeeding Douglas Hurd as foreign secretary. Patten demurred. ‘I did have a very strong feeling,’ he said privately a few weeks later, ‘that I didn’t want to hang around on the margins of contemporary domestic politics, collecting directorships, doing a bit of writing, with the terrible danger of starting to be afflicted with a sense of what might have been. I think it’s important, since we’re only here once, to look forward, not backward.’

Patten had long stated his private aversion to political carpet-bagging, or joining the ‘chicken run’, as the demeaning search for a safe seat was later disparagingly described. Moreover, he was too astute to presume that any Conservative seat would be safe in a high-profile by-election following the return of an unloved government. If he accepted a peerage, his future in public life would depend exclusively on the prime minister’s patronage: for an ambitious individual who was not yet fifty years old, the Lords seemed a remarkably precarious pinnacle from which to establish a position of sustained influence. He had no wish to become a supplicant at the court of Westminster.

Yet party politics had been his life, and he felt bereaved. On the Saturday following the election he helped the prime minister to select the new Cabinet and, he said, felt ‘a certain wry detachment’ when three of the new appointees rang him for advice about what to do and how to do it. Yet he had no sense that he should have been in their shoes: the ‘stabs and twists of anguish’ that did assail him sprang from the inevitable loss of companionship, the feeling that he was no longer a member of an intimate club and the recognition that half a dozen of his closest friends now inhabited a world from which he was excluded. He resolved to resist the temptation to resort to envy or bitterness. ‘Some people might find this barking mad, but the first time I had dinner with them, a...