The Creation of the Maginot Line

After the end of the First World War the victors and the vanquished in Europe suffered equally from the effects of four years of continuous warfare on a scale never seen before. While the French and British licked their wounds, they did not refrain from exacting retribution from the defeated in the form of crippling demands. The Austro-Hungarian Empire was broken up into a number of new states that included, among others, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia, which greatly weakened the Germanic domination of Central Europe. Germany and Austria both lost territory to the newly recreated Poland, which posed a serious barrier to German eastward expansion and left Berlin within easy reach of an old antagonist. Germany was also stripped of the long-disputed regions of Alsace and Lorraine, which had been appropriated by the Second Reich in 1871 after the humiliating defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian War. In addition to being burdened with massive war reparations, Germany, like most of Central and Eastern Europe, also had to face the social turbulence caused by the Communist movement.

Map of ouvrages on the Northeast Front.

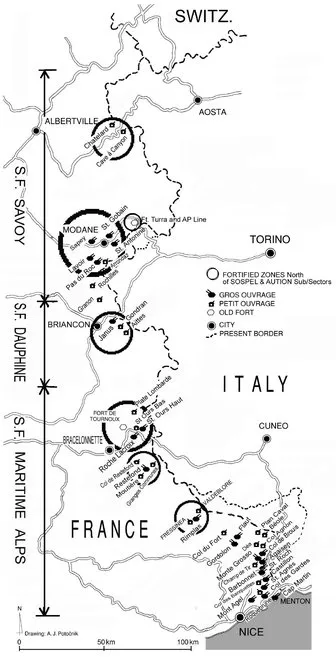

Map of ouvrages on the Southeast Front.

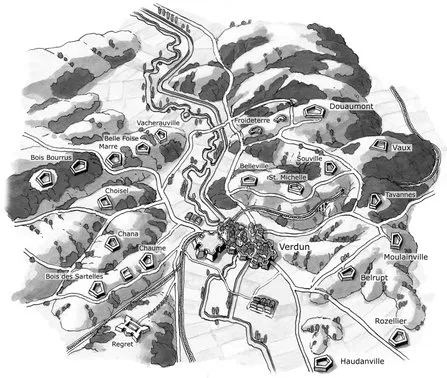

A view of Verdun. (A.J. Potočnik)

The French military leaders became increasingly concerned over the situation beyond their borders. The rise of Fascism in Italy in the early 1920s increased their unease, especially after Benito Mussolini made it known that he had set his sights on Nice and Corsica. Despite a rather unstable parliamentary system that led to frequent changes in the French government during the inter-war period, security of the national borders remained, for the most part, a priority. Since France had suffered substantial losses in manpower during the war, the high command concluded in the late 1920s, as their occupation troops prepared for their departure from the German Rhineland, that a defensive posture would be the best option. Offensive operational plans devised in the 1920s in the event of another war with Germany fell by the wayside; even the length of active service for conscripts was drastically reduced to only a year in the 1930s. The French military leadership eyed with suspicion the resurgent Germany long before Hitler created his Third Reich in the early 1930s. Actually, they contemplated the possibility of an aggressive Germany right after the First World War. As a result, early in the 1920s the Ministry of War ordered the army to study the problem and find a way to protect France’s new borders along the German frontier.

New French and German Forts of 1880 – 1914

After the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 – 1871, changes in technology required the development of a new type of fort. However, by the 1880s these new designs had also become obsolete due to the introduction of the high-explosive shell. Undeterred, the French as well as the Germans continued to create or expand their fortress rings. The French fortress rings protected the part of Lorraine still under the Tricolour, the Germans having taken all of Alsace and part of Lorraine at the end of the Franco-Prussian War. The design of the French masonry forts built during the 1870s can be attributed to General Raymond Adolphe Séré de Rivières. During this period Verdun became one of the key defended sites. In mid-1885 the high-explosive shell – called a ‘torpedo shell’ by the French because of its shape – was put into production and tested on an old French fort, demonstrating that these rounds could penetrate the earth and masonry protection of even the newest forts. This led to a new round of fortress building and the reinforcement of older ones. The French strengthened their existing forts with concrete, a process which required the uncovering of some of the subterranean positions, recovering them with about a metre of sand and pouring a couple of metres of concrete over the sand layer.

In the late 1880s in Belgium General Henri Brialmont designed a new type of fort, triangular or quadrangular in shape and consisting of a concrete citadel surrounded by a moat (fossé). Although the new French forts appeared to follow a similar layout, their combat positions were more widely dispersed instead of being concentrated in a central citadel. The forts built in the 1890s required protected positions for artillery that included armoured casemate and turret positions, but the latter did not start appearing on the French forts until the beginning of the new century. In fact, both the Germans and the French had developed gun turrets earlier, but after the 1880s they focused their interest on steel rather than iron turrets.

In the 1890s the Germans responded by building a new type of fort called Festen. Feste Kaiser Wilhelm II was the first of this type. Built at Mutzig in Alsace, it was more a group of defensive positions than a single fort. It was followed by additional festen in the fortress rings of Metz and Thionville in Lorraine. The French referred to them as fortified groups since they included well-dispersed positions over a much larger area than other forts of the era. The new French fortifications tended to have regular shapes surrounded by a fossé, while the festen, which covered larger areas, had irregular shapes but often retained the enclosing moat. During the 1890s and at the turn of the century both antagonists developed reinforced concrete (concrete poured over steel rods) and introduced steel turrets and armoured embrasures to their forts. Both types of fort included artillery blocks, infantry positions, casernes (barracks and troop facilities) and magazines. French artillery blocks seldom mounted more than a single gun turret and an observation cloche. The German festen, on the other hand, consisted of larger artillery blocks that mounted up to four gun turrets. However, the French as well as the Germans used standardised artillery and infantry weapons in their fortifications. The French artillery turrets usually mounted two 75mm guns and a few forts had a turret mounting one 155mm gun, although some forts with older cast-iron Mougin turrets from the 1870s mounted two 155mm guns. The Germans employed single-gun turrets that mounted either a 100mm gun or a 150mm howitzer. The French also used machine-gun turrets and their forts usually had a casemate for flanking fire with two 75mm guns, known as a Casemate de Bourges (named after the place where it was developed in the late 1890s). The Germans used 53mm and 77mm guns in some casemate positions, mainly for local defence. The French also used machine-guns and lighter calibre guns for the same purpose.

These are only a few of the similarities and differences between the German and French forts of the late nineteenth century. When the French military engineers, the Génie, studied these forts in the twentieth century, they combined what they considered the best features of both schools of fortification rather than confining themselves to their own tradition.

The military and political leaders of France quickly decided that the best way to counter any future German resurgence was to erect new defences, since the older ones had become largely outdated and, due to the return of Alsace and Lorraine, were many kilometres away from the new border. The French military establishment concluded that huge expenditure on military equipment was a poor option since the machinery of war often quickly became obsolete when a new war began. The alternative was to wait until the next war began before developing, testing and mass-producing new weapons, assuming there would be enough time to do so, as there had been in the First World War. The first step of the plan was to delay and prevent the enemy from advancing into French territory during the first few weeks of conflict while the army mobilised. The next step would be to hold the enemy for many months while the new instruments of war went into production. (Waiting to develop new equipment during the war was not practical, but this did not hinder French pre-war developments significantly. The army leaders still did not consider offensive action practical for the first year of the war.) This led to the idea of a massive commitment to fortifications that would stop a German offensive, even a surprise attack, and allow the army several weeks to mobilise.

The first committees that were to address this question were formed under the aegis of Minister of War André Lefèvre in March 1920. General Joseph Joffre was appointed to lead a special committee, but his antagonist Marshal Philippe Pétain rejected his plans out of hand. By 1922 the group had dissolved. Joffre, the victor of the First Battle of the Marne, and a strong believer in offensive tactics before 1914, had no use for defence-minded officers and little interest in the defensive operations. Despite his personal philosophy, he felt that heavily fortified positions like the older fortress rings of Verdun, built after the 1870s, served a purpose in warfare, but needed to be modified. He endorsed the idea of concentrating heavy fortifications in vital sectors, which would allow the army to hold key positions in the face of an enemy advance. This would allow any French offensive room to manoeuvre. On the other hand, Pétain, the hero of Verdun in 1916, took a dim view of such heavily fortified locales. He proposed instead a continuous line of lighter positions that could be reinforced and built up with ‘mobile parks’ during wartime. These ‘mobile parks’ would consist of stockpiles of engineering equipment and materials that could be moved quickly into threatened sectors to build or reinforce the defences.

A new commission headed by General Louis Guillaumat quickly went into operation in the spring of 1923 and laid out a proposal for a defensive scheme that represented a compromise between the ideas proposed by Joffre and Pétain. An almost continuous line, as visualised by Pétain, would protect the threatened frontiers, but the strongest fortifications would be concentrated in fortified sectors, as proposed by Joffre. Once this was done, the commission spent some time agreeing upon the trace of this new fortified line and the types of position to be built. Meanwhile, the Commission d’Organisation des Régions Fortifiées (CORF) was established at the end of September 1927. Until it was dissolved in 1935, CORF was responsible for the final design and emplacement of the fortifications. Except for some experimental work, the construction of the Maginot Line began in late 1929, after André Maginot was reinstated as Minister of War.

From the early 1920s the French military leaders frequently visited and studied the existing fortifications, especially those at Verdun. The Battle of Verdun in 1916 provided them with a number of lessons in the design and use of fortifications. When the Treaty of Versailles returned Alsace and Lorraine to the French, they also inherited the German festen begun in the 1890s around Metz and Thionville, undoubtedly the most modern forts of the era. The French engineers did not fail to examine their features.

The French military authorities had many forts from the First World War era that they could study, but those of the Verdun Ring offered lessons based on wartime experiences that had a profound effect on the Maginot Line. Although Verdun was considered to be the strongest of the French fortified rings, the French high command had decided that its fortifications were obsolete shortly after the war broke out in 1914. This conclusion was reached when German heavy artillery, which ranged from 300mm guns to the huge 420mm mortars known as ‘Big Berthas’, devastated the Belgian fortress rings at Liege and Namur and the isolated French frontier fort of Manonviller on the border of Lorraine. At the Belgian forts the concrete had been poured in layers, making them weaker than the French fortifications. (Many of the Maginot fortifications required thicker layers of concrete. Since it was not possible to pour an entire slab in the few hours allotted to the task, special techniques were used to bind in the next pouring to avoid some of the problems associated with separate layers.) Fort Manonviller, on the other hand, was an older fort that had been modernised at the turn of the century, but, like several other French forts of the same generation that had been reinforced with sand and concrete, it was still too vulnerable.

After the disasters in Belgium and at Manonviller, the high command assumed that all the French forts were untenable and ordered most of the large garrisons and some of the weapons to move out and take up positions at the front. Before long, Verdun found itself located on the battlefront. Most of the 500-man garrison at Fort Douaumont, the pride of the French forts, had been removed, and only a skeleton crew remained within to man the 155mm gun turret that could be used as long-range artillery. Fort Douaumont and most of the other forts of the Verdun Ring remained virtually undefended.

At the opening of the Battle of Verdun on 21 February 1916 the German assault troops tried to break the strongest point of the Anglo-French front. Troops from the Brandenburg Korps worked their way to the glacis of the much-vaunted Fort Douaumont. The previous bombardment had created some gaps in the wire and rail-like obstacles on the glacis. A few combat engineers got into the moat and entered a coffre or counterscarp casemate. Three of them took the underground passage beneath the moat that led into the fort, and a...