![]()

1

‘In Arms We Rise’:

The Military Establishment

Our Country calls, in arms me rise

To guard fair Britain’s isle

Defiance to Bonaparte:

A New Martial Song, by Morva , 18041

From a position of government parsimony and a lingering mistrust of the very concept of a standing army, a legacy of the consequences of the English Civil War, the needs of the war against France led to military and naval affairs becoming the overriding concern of the state. War dominated national finances: in 1803, almost 60 per cent of the entire annual expenditure went on the army and navy; by 1814, including military subsidies to allies, this had risen to about 68 per cent. This was reflected in the strength of the armed forces: on New Year’s Day 1804, some 236,112 men were in full-time military service; by September 1813, this figure had risen to 330,663. The 1811 census revealed that there were 5,693,587 males in Great Britain; even when Ireland is included, it is obvious that the 319,033 soldiers serving in January of that year represented a considerable proportion of the entire population. The maintenance of such numbers involved the replacement of casualties; with deaths in battle and incapacitation from injury and disease, the average loss between the resumption of war in 1803 and the end of 1813 was about 20,500 per annum, with a total during this period of 225,796, the high point being the 25,498 men lost to the service in 1812.

It is against this background that the career of the Redcoat should be considered, though his own perception of the military establishment was restricted largely to his own regiment. The regiment was the army’s principal administrative unit, and it was with the regiment that the ordinary soldier most identified. The military force of the state was divided into the army, comprising the infantry and cavalry regiments, controlled by the Commander-in-Chief at Horse Guards; and the ordnance services, the artillery and engineers, under the jurisdiction of the Board of Ordnance, headed by the Master General. To the ordinary soldier, this division of responsibilities was of little consequence; nor was he much concerned with the commissariat, which was controlled by the Treasury, beyond the fact that on campaign his rations were often late in arriving.

The ethos of the regiment has always been regarded as one of the greatest assets of the British military establishment, a golden thread running down the centuries that connected soldiers with their forebears. It is more than a focus for emulation of the past, important though that is; the regiment can provide an alternative family to the soldier’s blood kin, and a vital bolster to morale in time of trial. The regimental system has matured over the centuries; although a number of regiments that served in the Napoleonic Wars dated only from the beginning of that period, many were already of considerable antiquity with a distinguished past. For example, excluding the King’s German Legion, of the 39 regiments present at Waterloo, seventeen had been raised in the seventeenth century, ten in the first half of the eighteenth century and nine between 1755 and 1780. Regimental longeivity was not the only significant factor, however; the most junior regiment at Waterloo, the 95th Rifles, formed in 1800, had one of the strongest regimental identities and esprit de corps, arising from their elite status, unique mode of operation and distinctive uniform.

Regimental identity was marked and fostered not only by history but by insignia and even by nicknames, so that most soldiers identified with their regiment much more than with the army in general, which had a marked effect upon morale. A writer who interviewed many officers who had fought at Waterloo stated that many had expected to be beaten and that other regiments would give way, but ‘certainly not my own corps’. ‘Such was the universal answer; and this is the true English feeling: this indignancy of being even supposed to be likely to be the first to give way before an enemy is the true harbinger of success . . . . Our regiments, accustomed to act and live alone, are not taught to dread the failures of adjoining corps in combined operations; they cannot readily yield to the belief that the defeat of a corps in their neighbourhood can license themselves to flee; penetrate an English line, you have gained nothing but a point; cut into a continental line, even a French one, and the morale of everything in view, and vicinity, is gone. The English regiment will not give way, because the English regiment of the same brigade has done so, but will mock the fugitive, and in all likelihood redouble its own exertions to restore the fight – a true bull-dog courage against all odds – if well led.’2

This belief in the superiority of an individual’s particular regiment would be recognized by many generations of British soldiers; but at the time it was not an entirely positive emotion. While some corps maintained unusually cordial relations with others that had shared in some great event (for example the relationship between the 1st Foot Guards and 15th Hussars, dating from the Netherlands campaign of the French Revolutionary Wars), others bore grudges. A case was quoted of a regiment moving into a shared camp in Ireland, and almost immediately launching into an attack on the neighbouring encampment, first with fists and then bayonets; because the aggressor corps could not forgive the other for supposedly deserting them in an action during the Seven Years War, almost half a century earlier, when hardly any of the soldiers involved would even have been born.

Similarly, regimental pride could overflow into unjust criticism, such as that which fell on the 4th Foot after the French garrison had been allowed to escape from Almeida in 1811. Regiments that attracted much public attention discomfited equally worthy corps that felt themselves overlooked; in some quarters this applied to the Highland regiments whose distinctive dress and traditions attracted much attention. An extreme example of this bias was articulated by Joseph Donaldson, who declared the 42nd Royal Highlanders guilty of ‘egotism and gasconading’, with their reputation as doughty fighters arising from the fact that they had ‘got into scrapes by want of steadiness’ and then having to fight desperately to save themselves. What had they done to warrant their great reputation? ‘Nothing – absolutely nothing: they are a complete verification of the proverb, “If you get a name of rising early, you may lie in bed all day.”’3 It might not be unreasonable to suggest that at least some of Donaldson’s unfair prejudice arose from the fact that his own regiment had not attracted the public plaudits that its perfectly respectable career deserved.

Although no regiment would have admitted it, some were fairly undistinguished at times. Among well-known cases, Wellington threatened to send home the 18th Hussars from the Peninsula if they did not improve, and it was stated that one of the causes of the failure of the attack on the American positions at New Orleans was because the 2/44th, carrying ladders and fascines to overcome the enemy defences, was badly led and either threw down their burdens or turned tail, and it was after attempting to halt them with cries of ‘For shame! recollect that you are British soldiers!’4 that the British commander, Sir Edward Pakenham, was mortally wounded. Nevertheless, the members of such regiments would still have averred that their regiment was superior to all others.

The infantry’s principal tactical element was the battalion. A regiment comprised one or two battalions, occasionally up to four, with the 60th (Royal Americans) eventually maintaining eight. Any intention that a regiment’s 1st Battalion would go on service, leaving the 2nd Battalion at home to provide reinforcement drafts, was negated by the pressing need for troops, so that many 2nd Battalions also went on campaign. At the conclusion of the Peninsular War, for example, the field army comprised forty-two 1st Battalions or single-battalion regiments, thirteen 2nd Battalions, four 3rd Battalions and the 5th Battn. 60th. Each battalion comprised ten companies, eight ‘battalion’ or centre companies and two ‘flank’ companies, these terms deriving from their position when the battalion was drawn up in line; the flank companies consisted of one of grenadiers, in theory the battalion’s most stalwart, and one of light infantry, trained in skirmishing. Each company had a notional strength of 100, so that each battalion was nominally 1,000 strong, but these numbers were hardly ever attained: on the day of Waterloo, for example, excluding those that had suffered severe casualties at Quatre Bras two days earlier, including the four detached at Hal but excluding the 3/95th, which had only three companies present, the average battalion strength was 752. At the outset of the Vittoria campaign, another case in which there had been no reduction in numbers from the attrition of campaign, the average strength was 680. This attrition could be profound; in 1814 it was remarked of the men who began its Peninsular service (it was 778 strong in its first battle at Talavera), only seven ‘other ranks’ of the 1/61 st were still serving, including the brothers Robert and William Hogg. Not only did they survive a combined total of fifteen battles, but both lived to be awarded the Military General Service Medal in 1848.

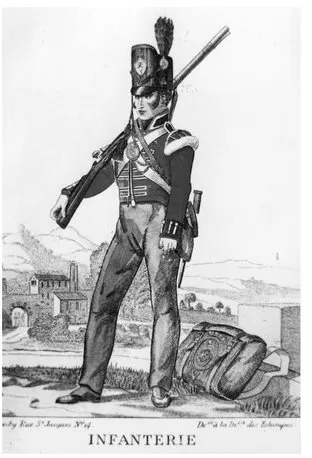

The classic ‘redcoat’: a private of the light company of the 5th (Northumberland) Regiment in the uniform of 1812-15. The green plume was indicative of light infantry and the regimental identity is emblazoned on the knapsack. (Print by Genty)

The infantry comprised three regiments of Foot Guards, traditionally the monarch’s bodyguard, and consecutively-numbered ‘line’ regiments, the numbers in 1815 running from the 1st (Royal Scots) through to the 104th, although in the French Revolutionary Wars the number had extended to the 135th (Limerick), the higher-numbered corps of only brief existence. From 1782 most regiments had been allocated a county affiliation, with the intention of enhancing morale and aiding recruiting, but for many the connection with a specific county was tenuous. Of the regiments existing in 1815, fifteen had Scottish titles (and three more had been ‘Highland’ until 1809), eight were Irish and two bore Welsh titles. The latter exemplify the diverse nature of recruiting: the 43rd (Monmouthshire) Light Infantry was never an overtly Welsh corps despite its title (when county titles were allocated the regiment had expressed a desire not to have one and had declared that its primary recruiting ground was Cleveland); while that most Welsh of corps, the 23rd (Royal Welch Fuzileers) at Waterloo comprised less than 27 per cent Welshmen, with 8 per cent from both Lancashire and Norfolk and 7 per cent from Ireland. The Scottish regiments generally retained a regional identity more than the English, although those officially ‘Highland’ could not draw sufficient recruits from that area to reflect their title, a principal reason why a number lost their ‘Highland’ designation and costume in 1809. For example, arguably the most famous of the Scottish regiments, the 42nd (Black Watch), between 1807 and 1812 enlisted about 87 per cent Scots, almost 9 per cent Irish, and the remainder English, while in 1811, the 93rd Highlanders was almost 97 per cent Scottish. Conversely, the 3/lst (Royal Scots) during its existence appears to have recruited only 18 per cent Scots, but 42 per cent Irish and 37 per cent English. The dilution of regional identity became much more marked when volunteers were accepted from the county militia regiments, who rarely joined the line regiment associated with their own county.

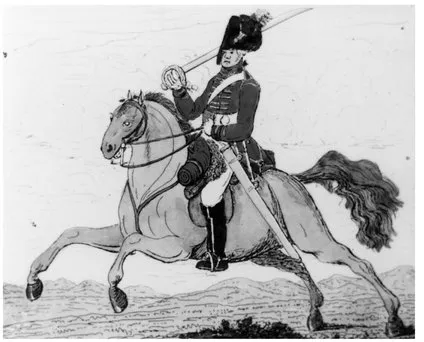

Heavy cavalry: a dragoon in the uniform worn until the introduction of a French-style helmet and short-tailed jacket from 1812.

While identifying most readily with his regiment, it was with his company, with its familiar complement of officers and NCOs, that the soldier would feel closest. Officially there was no lower sub-unit, but in May 1809 for his army in the Peninsula, Wellington instituted the formation within each company of ‘as many squads as there are Non-Commissioned Officers’ in an attempt to check looting by the closer supervision of the NCOs, there being ‘no description of property of which the unfortunate inhabitants of Portugal have not been plundered by the British soldiers.’5

Each cavalry regiment was divided into a number of squadrons, each of usually two troops, with each regiment commonly of ten troops, two of which formed the depot and the remainder went on service. The number of ‘service’ troops was reduced to six in 1811, with light regiments maintaining ten, increased to twelve in 1813. Strengths varied considerably on campaign; for example, at the beginning of the 1809 campaign average regimental strength was 385; at the beginning of the Vittoria campaign, 412, and at Waterloo, 441. The cavalry comprised two regiments of Life Guards and the Royal Horse Guards, together forming the Household Cavalry (though the status of the Royal Horse Guards was not confirmed until 1820); the heavy cavalry comprised seven regiments of Dragoon Guards, six of Dragoons (reduced to five in 1799 when the 5th Dragoons was disbanded following infiltration by Irish rebels). The Light Dragoons were numbered consecutively after the 6th Dragoons, 7th-33rd, the later-numbered corps of ephemeral existence, so that the 25th was the highest number in use by 1815. The 7th, 10th, 15th and 18th Light Dragoons were granted the additional title (and uniform) of Hussars. In general, cavalry regiments had no county affiliation, though the 2nd Dragoons was predominantly Scottish and the 5th and 6th Dragoons Irish.

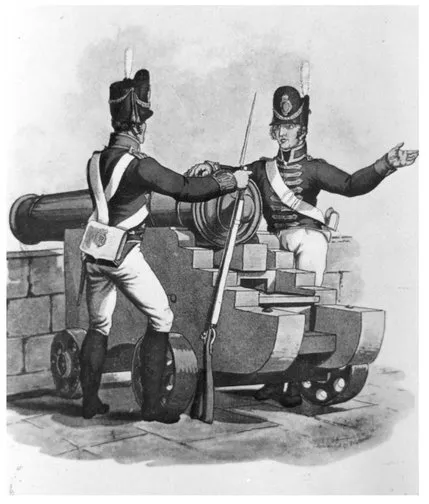

Gunners of the Royal Artillery in the uniform of 1812. (Print by J.C. Stadler after Charles Hamilton Smith)

The Royal Artillery was also organised in battalions, but never served as such; each six-gun unit was manned by a company (sometimes styled a ‘brigade’), or by a troop in the case of the Royal Horse Artillery. These were autonomous units, usually including a detachment from the Corps of Drivers, so that the focus of the gunner’s existence was not his battalion but his company or troop.

Other types of regiment competed with the regular army for recruits. During the French Revolutionary Wars there were corps of infantry and cavalry Fencibles (their name derived from ‘defencible’), which were regularly recruited but liable for service only within the country in which they had been raised unless they volunteered to serve elsewhere; none survived beyond the Peace of Amiens. More substantial was the Militia, battalions of infantry raised on a county basis for service at home, especially valuable in releasing regular troops for overseas service. This was the only category of regiment not raised entirely by voluntary enlistment, as men could be compelled to serve by ballot, a form of selective conscription; but it was possible to obtain exemption by paying for a ‘substitute’, so that only a small number of militiamen were ‘principals’ or conscripts. The hiring of such substitutes took away many potential recruits from the regular army, but when militiamen were allowed to volunteer for regular service, the regular army gained a priceless resource of new recruits who were already inured to military discipline and trained in the use of arms.

There was in addition a huge force of part-time volunteers formed for the defence of their own localities – in December 1803 no less than 380,193 in mainland Britain plus 82,941 in Ireland – who drilled once or twice a week and who acted as a form of security force in times of civil disturbance; but they had little bearing upon the regular army beyond giving some men a taste for a military life.

![]()

2

‘Come ’List and Enter Into Pay’: Recruiting

Come ‘list and enter into pay,

Then o’er the hills and far away

Anon

The Duke of Wellington’s most notorious remark arose largely from a comparison of the British system of voluntary enlistment with the conscription utilized by some European armies, and without the closing phrase, often omitted, the remarks seem savagely critical:

‘ . . . our friends [the ordinary British soldiers] are the v...