![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Origins and Development

On 25 November 1917 the four vessels of Battleship Division Nine, accompanied by the destroyer USS Manley as escort, departed from Lynnhaven Roads, Virginia, bound for the anchorage of the Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands. Regarded as an uneventful transit, it was complicated by storms that increased in ferocity as the voyage continued. After battling through the weather, Battleship Division Nine arrived at Scapa Flow on 7 December.

Having survived their introduction to the Atlantic, the four battleships were assigned to the Sixth Battle Squadron of the Grand Fleet. While their role would be one of blockade, one thing did impinge itself thoroughly upon the US Navy officers, was the number of aircraft being carried aboard the ships of the Royal Navy. Not only were the battleships and battlecruisers complete with a range of aircraft, the fleet’s cruisers also carried aircraft, and even the destroyers were capable of launching aircraft, although these smaller vessels towed their aircraft for launching on lighters.

The irony is that the US Navy was the pioneer in launching aircraft from naval vessels. The first attempt was courtesy of Samuel P. Langley, whose model of the ‘Aerodrome’ was undertaking successful flight trials in 1896. Such was their success that the US Government would issue a contract in 1898 for a full-scale version of the ‘Aerodrome’. While Langley was building his aerial machine, the US Army and the Navy convened a joint board to study the future of flight in both services. Unfortunately for both, the Langley ‘Aerodrome’ failed its flight trials from the Potomac river at the end of 1903. It would be another five years before the US Navy took an interest in flying machines again. Two officers would be present when the Wright Model ‘A’ undertook its flight demonstrations at Fort Myer in September 1908. Other officers would observe flight demonstrations at home and abroad, and all would report enthusiastically upon the benefits to the US Navy of aircraft that could operate from ships. While the views within the US Navy concerning aviation were diverse, an important step was taken on 26 September 1910 when Captain W.I. Chambers was designated as the officer in charge of naval aviation, a position he would hold for the next three years. As for Langley, while his aircraft was a failure, he would be commemorated by the naming of Langley Field in Virginia to celebrate his efforts.

The pioneer of US naval aviation was Eugene Burton Ely. Between 22 and 30 October 1910 Captain Washington I. Chambers, who was responsible for aviation matters at the Navy Department, would travel to Belmont Park, New York, to inspect the participating aircraft and meet pioneer aviators at the International Air Meet. While discussing the prospects for taking aircraft to sea, he was impressed by the technical abilities of Eugene Ely, a test and demonstration pilot working with the aircraft constructor Glenn Curtiss. From New York the captain would visit another air show near Baltimore, Maryland, where again he saw Ely undertaking flight demonstrations. After discussions between the pilot and Captain Chambers concerning the possibility of flying an aircraft from a ship, Ely volunteered for the task.

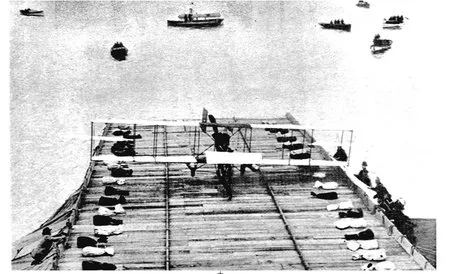

It took less than two weeks to start the process with financial help from a wealthy aviation enthusiast, John Barry Ryan, official backing from the Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Beekman Winthrop, and the drive of Eugene Ely for Chambers to achieve the event that marked the beginning of flying by the US Navy. At the Norfolk Navy Yard, Virginia, an 83 ft wooden platform was rapidly constructed over the foredeck of the cruiser USS Birmingham. Designed by the naval constructor William McEntree and paid for by John Barry Ryan, this structure sloped down five degrees from the cruiser’s bridge to the bow to provide a gravity-assisted 57 ft take-off run for the Curtiss pusher aeroplane supplied for the trials.

The aircraft was lifted aboard the cruiser on the morning of 14 November 1910, and after it had been secured to the deck the engine was installed by Ely and the accompanying mechanics as the ship prepared to leave port. Shortly before noon USS Birmingham steamed down the Elizabeth river toward Hampton Roads where the flight was to take place. However, the weather deteriorated rapidly, with squalls rolling by, thus threatening to put a stop to the trials. Unable to carry out the trials, the USS Birmingham anchored to await an improvement in conditions. By mid-afternoon, with conditions showing signs of improvement, the vessel began to raise the anchor chain. Eugene Ely was occupied in warming up the aircraft’s engine and checking its controls, waiting for the weather to clear. Noticing that visibility was again deteriorating, he concluded that the flight had to be made as soon as possible, even though the ship was still stationary. At 3.16 p.m. the pilot opened the engine throttle to full power, gave the release signal, rolled down the ramp and was airborne. Getting airborne was a bit of a struggle, as the Curtiss briefly touched the water, throwing up enough spray to damage its propeller, which caused heavy vibration through propeller imbalance as it climbed to height. Eugene Ely, a non-swimmer, realised that a quick landing on dry land was a priority, especially as his goggles were covered with spray. Fortunately Ely was able to land on nearby Willoughby Spit after some five minutes in the air. This two-and-a-half-mile flight, the first time an aircraft had taken off from a warship, was seen as something of a stunt, although it would receive wide publicity. After this flight Ely was made a lieutenant in the California National Guard to qualify for a $500 prize offered to the first reservist to make such a flight. On 18 January 1911, in San Francisco Bay, Eugene Ely would again operate from a ship, landing and taking off from the armoured cruiser USS Pennsylvania. During the landing the Curtiss pusher touched down on a platform on the Pennsylvania, which was anchored in San Francisco Bay, using the first-ever tail hook system to arrest the landing. This innovative item had been designed and built by circus performer and pioneer aviator Hugh Robinson.

A most important photograph, the Eugene B. Ely taking off from the cruiser USS Pennsylvania in January 1911.

(Library of Congress/ Dennis R. Jenkins)

Having successfully shown the US Navy that aviation from ships was possible, Ely contacted the US Navy for a job. However, the service was not organised for such a role yet, and he was informed that his application would be kept in mind. Unfortunately this would never happen, as on 19 October 1911 while flying at an exhibition in Macon, Georgia, his aircraft was late pulling out of a dive and crashed. Ely managed to jump clear of the wrecked aircraft, but his neck was broken and he died a few minutes later. In 1933, in recognition of his contribution to naval aviation, he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross posthumously by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

On the day following Ely’s landing aboard the Pennsylvania, Lieutenant Theodore G. Ellyson began the flight training that would make him the first aviator in the US Navy. Ellyson had been ordered to the Curtiss aviation camp at North Island, San Diego, California, to undergo flight training. He would qualify for his Aero Club of America licence on 6 July 1911, using the Curtiss A-1 Triad, this being the first aircraft purchased by the Navy. He subsequently became Naval Aviator No. 1 on 4 March 1913. The Curtiss A-1 Triad was also utilised in the Navy’s first attempt to launch an aircraft using a compressed air catapult developed from a naval torpedo launcher, at Annapolis in 1912. The launching from a purpose-built deck failed due to a crosswind gust that blew the A-1 into the water. Also contributing to the launch failure was the inadequate restraining of the aircraft during engine run-up, so that the A-1 was airborne before the control surfaces became effective. A further attempt on 12 November was successful when a Curtiss A-3 piloted by Ellyson was launched at the Washington Navy Yard. The A-1, as the only naval aircraft at the time, would set numerous records, including flying from Annapolis, Maryland, to Milford Haven, Virginia, in 122 minutes, with Ellyson as pilot and Lieutenant John H. Towers as passenger. The A-1 would also be the first naval aircraft to carry a radio, although this was not very successful. More successful was the setting of a seaplane record of 900 feet on 21 June 1912.

That same year, the US Marine Corps entered the world of aviation, and from that time Marine aviation would develop in parallel with its naval counterpart. To celebrate this, Lieutenant Alfred A. Cunningham USMC reported to the aviation camp at Annapolis for duty in connection with aviation, arriving on 22 May 1912. He undertook his flight training at the Burgess aircraft factory in Marblehead, Massachusetts, being awarded his certificate as Naval Aviator No. 5.

Deployment of a small group of flyers, the entire aviation complement of the Navy, took place during January 1913, to cover fleet manoeuvres at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. These demonstrated the operational capabilities of the available aircraft and stimulated further interest in aviation within the Navy. The first test of naval aviation at sea revealed some deficiencies in existing aircraft when two aviation detachments took their aircraft to Veracruz in the spring of 1914 to bolster US forces during the Mexican crisis. During one reconnaissance flight Lieutenant P.N.L. Bellinger returned to base with holes from hostile bullets through the skin of his aircraft, this being the first combat damage received by a Navy aircraft.

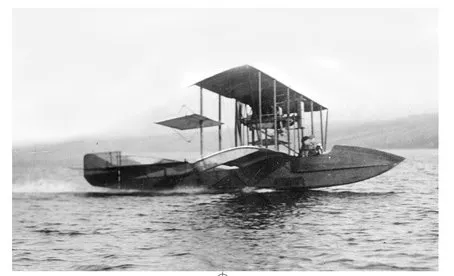

The Glenn L. Curtiss Aircraft Company would be the first manufacturer to supply the US Navy with aircraft. This is one of the early hydroplanes.

(Library of Congress/ Dennis R. Jenkins)

When the Great War began in Europe in July 1914, naval aviators were sent there as observers to report on aviation developments from bases in London, Paris and Berlin. The importance of aviation in the future of the US Navy was officially recognised in November 1914 with the creation of a Director of Naval Aeronautics. This appointment was followed during 1915 and 1916 by advances in technology, experimentation and new administrative procedures, all of which pointed to an increased role for aviation in the US Navy. During this period of change the first contract was awarded for the provision of a lighter-than-air craft, while the Aeronautical Engine Laboratory was set up at the Washington Navy Yard. This was followed by a Naval Appropriations Act that provided for a Naval Flying Corps that would be reinforced by a Naval Reserve Flying Corps.

During the nineteen-month period that the Naval Flying Corps was involved in the Great War the service saw a rapid expansion in its size. In April 1917 the corps had fifty-four aircraft on strength, manned by forty-eight qualified and student pilots, all at one base. By the end of the war the Navy had twelve air bases in America, plus a further twenty-seven in Europe from which the Naval Flying Corps had attacked twenty-five U-boats, sinking or damaging at least half of them. Operating from these bases were 6,716 officers and 30,693 enlisted men, and attached to them were 282 officers and 2,180 enlisted men from the USMC. This manpower operated 2,107 aircraft and fifteen dirigibles.

As with all services, the Naval Flying Corps underwent serious contraction at the cessation of hostilities, although the Bureau of Aeronautics did pursue the development of emerging technologies with vigour, including both aircraft and their carriers. This was not without its problems, as the US Army was determined to be the only aerial operator in America. However, the Navy managed to outflank the Army as its mission requirements were always different from those of land-based air forces. Eventually a legal termination to the various wrangles was needed, and the MacArthur-Pratt agreement of January 1931 defined the naval air force as an element of the fleet that was designed to move with it and assist it in carrying out its primary task.

To promote the aerial side of the Navy, the Bureau of Aeronautics was formed in August 1921 to assume responsibility for all matters concerning aircraft, personnel and their usage. The BuAer became the aviation department of the Secretary of the Navy’s office, and would remain so until 1959. While the USN and the Marine Corps operated a similar range of aircraft, their aircraft needs were dealt with by the Director of Aviation at Headquarters, Marine Corps. During the period of inter-war contraction, the aircraft strength of the Navy fell to 1,000 machines in the 1920s, although it slowly climbed to 2,000 aircraft by 1938. Meanwhile rumblings of discord in Europe were becoming more perceptible, and there were signs of the Japanese thinking about spreading their influence over the whole of the Pacific, all of which was increasing global tension. The American answer to that was the Naval Expansion Act, which authorised the number of usable aircraft to increase to at least 3,000. This had risen to 4,500 by June 1940, although this was quickly added to by increases in the following months, which saw the level reaching 15,000 aircraft.

The third service with an interest in sea-going affairs was the US Coast Guard, this organisation being seen as an extension of the US Navy in periods of war. In more peaceful times, however, the USCG regarded the aircraft as a possible search and rescue tool, and in 1915 three Coast Guard officers based at Hampton Roads, Virginia, developed the concept of air patrols to search for disabled vessels along the Atlantic seaboard. To that end Captain R...