![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Beginnings

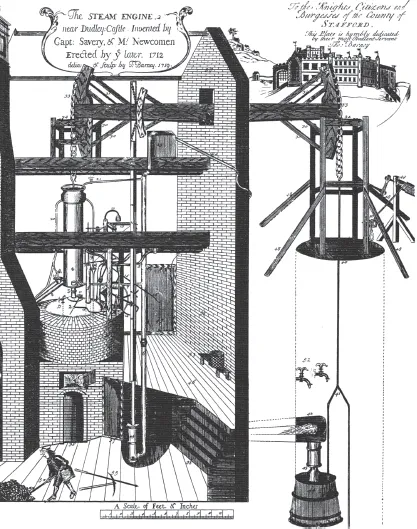

Almost a century had passed since the invention of the first successful steam engine before engines went on the move. The story of steam began with the need for more efficient pumps to drain water from deep mines. There was an early device, known as ‘The Miner’s Friend’ designed by Captain Savery in 1698, but it did not lead to any further developments and was never widely used. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, however, a Dartmouth man, Thomas Newcomen, began experimenting with a different idea and the first of his engines was installed at a coal mine at Dudley in the Black Country in 1812. Pumps were worked by means of an up and down motion of the pump rods – in its simplest form by working the handle at the village pump. Newcomen’s pumps were on an altogether grander scale. The pump rods were hung from one end of a pivoted overhead beam, and dropped down under their own weight. What Newcomen supplied was a force to raise them up again. At the opposite end of the beam was a piston fitting snugly into a cylinder. Steam was allowed in under the piston and then condensed by spraying with cold water. This created a partial vacuum under the piston and air pressure forced it down, pulling down that end of the beam and so lifting the rods at the other end. Pressure equalised, gravity took over again to pull the rods down, and set in motion the see-sawing of the beam and the rise and fall of the pump rods.

Newcomen’s engine undoubtedly did the job it was designed to do, and soon the massive engines were nodding over shafts from the tin and copper mines of Cornwall to coal mines in Scotland. The engine was, however, extremely inefficient, thanks to the energy needed for constantly having to reheat the cylinder after each stroke. This was not particularly important at coal mines where fuel that might not have been good enough for sale was quite adequate for feeding the boilers. It was far more troublesome in Cornwall, where fuel was mainly imported across the water from South Wales at a great cost. The Cornish engineers did their best to try to improve the engine, but gains were only marginal. It was a young Scottish instrument maker at Glasgow University who spotted the nature of the problem and saw a solution.

Thomas Newcomen installed this, his first atmospheric engine, at a colliery in Dudley. For almost all of the next two hundred years the only steam engines in use in Britain were immense beam engines, such as this. All these engines worked at low pressure and the massive stone-built engine house was an essential part of the structure.

James Watt’s solution was to condense the steam in a separate vessel so that the cylinder would not lose heat by being constantly drenched in cold water. But heat would still escape through the open top of the cylinder. To solve this problem, he closed the top and instead of air pressure pushing down the piston, he used steam pressure. The atmospheric engine had become a true steam engine. Watt went into partnership with the Birmingham businessman Matthew Boulton and set up a company to manufacture the new engines, and they took out a patent to protect the invention. It soon became clear, that by allowing the steam to be forced alternately onto either side of the piston, there was no need for pump rods to provide the movement in one direction. And if the piston could be moved up and down using steam alone, it would be a simple matter to convert this up and down motion to turn a wheel. The first application was to drive the machinery of textile mills, but others saw new possibilities.

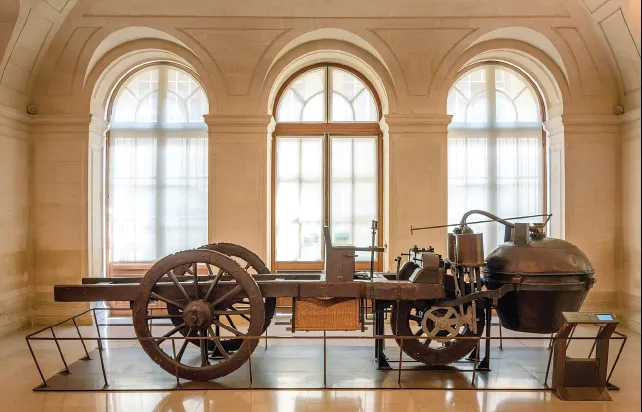

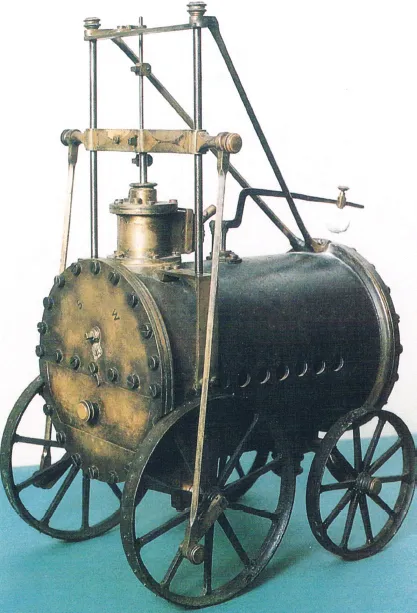

Given that all the early development of steam power had taken place in Britain, it is perhaps a little surprising that the first successful experiments to use steam engines for land transport took place in France. Perhaps British inventors were put off by Watt’s all-embracing patent. It was a retired French army officer, Nicolas Joseph Cugnot, who had seen the problems involved in lugging heavy artillery around using horses, and decided that a steam engine might offer a better solution. He set about designing a steam tractor and his prototype, a quite extraordinary device, was put through its paces in 1769. It was a three-wheeled vehicle. The spherical boiler was suspended above the single front wheel and steam fed down to pistons on either side of the same wheel. These connected with a ratchet to provide the drive. As that same wheel was also the one that could be steered it must have been all but unmanageable. He built a second version in 1770, which was no more manageable than the first. In fact a story, probably apocryphal, has it that on the first run it got out of control and demolished a brick wall at the French arsenal, at which point the authorities banned it. Whether true or not, what we do know is that the experiment was never followed up. The prototype was, in any case, virtually useless in battle conditions as it lacked an essential ingredient – a feed pump. As a result, when the boiler ran low on water the whole machine had to be stopped, everything allowed to cool down and then refilled. Meanwhile, presumably, the ‘old fashioned’ horse-drawn carriage would have hurried on to the front.

Nicholas Joseph Cugnot’s was the world’s first ever steam-powered road vehicle. The prototype first appeared in 1769 and was intended to be used as a tractor for artillery. It was never accepted by the military and after its unsuccessful trial this model, the second version of 1770, eventually found a home in the Musée des Arts et Métiers in Paris.

France was to see a far more successful experiment with steam when the Marquis Jouffroy d’Abbans devised a paddle steamer that was sufficiently successful for it to go into service on the River Saône in 1783. Any chances that France might become a centre for steam innovation vanished, however, when the country was plunged into political revolution. The technological events in France went largely unnoticed across the Channel in Britain. Steamboat development did get under way before the end of the eighteenth century, but work on road vehicles took a little longer.

James Watt’s patent stifled competition and there was one point on which he was adamant: high-pressure steam was anathema. If you needed more power, you simply built larger engines and pumping engines became enormous; the largest ever built by the Cornish firm of Harvey of Hayle had a massive 144-inch diameter cylinder. These monsters were firmly and immovably rooted to the spot. Among the places where Boulton & Watt received a huge welcome at first was Cornwall, but the Cornish engineers were used to making their own innovations and changes. This was firmly resisted by Boulton & Watt and those who tried to introduce changes soon found themselves on the wrong end of lawsuits. One of the men who was opposed to police affairs in Cornwall, supervising the erection and use of engines and tracking down steam pirates trying to evade the patent was William Murdoch (sometimes spelt Murdock). Yet he was the man who was secretely working on the heretical notion of using high-pressure steam to create a powered road vehicle.

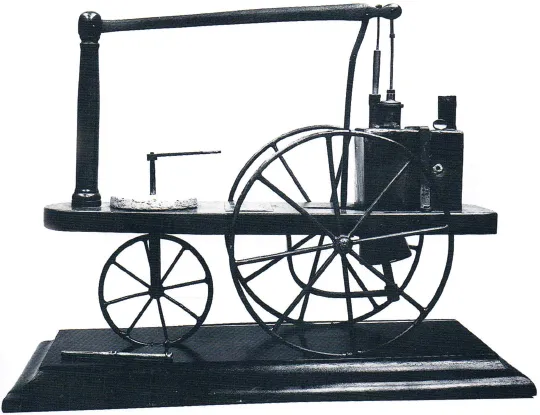

Murdoch produced a working model, which, like Cugnot’s was three-wheeled, but rather more manageable. The boiler was set at one end of a platform, with a vertical cylinder embedded in it. A beam took the drive from the piston rod to a crank to turn the front wheel. In order to keep his activities secret, he made his trials at night. On one of these nights, he set the model in motion in a narrow lane by the church in Redruth. He set off to trot after it, when he heard anguished cries. It turned out that the local vicar had also been coming home in the dark, when he saw a fiery monster approaching. He was, he later declared, certain he had met ‘the Evil One’. The vicar was calmed down, but inevitably news of the experiment reached the ears of Boulton & Watt. Murdoch had broken all their most cherished rules; the engine did not use a condenser at all, but worked with what was then referred to as ‘strong steam’. By 1795 he had built three experimental models and was ready to apply for a patent. He set off for London on the pretext of looking for skilled men to come to Cornwall, but was confronted by Matthew Boulton, who made it clear that the company was aware what was going in and would vigorously oppose his application. The heretic was given a straight choice – continue his experiments and leave the company or remain in an important and well paid job. He wisely chose the latter and was to go on to make other discoveries and inventions, notably introducing gas lighting

William Murdoch was the first to attempt to design a steam carriage in Britain. He never progressed further than constructing and experimenting with a model. He was about to apply for a patent in 1795, but his employers, Boulton & Watt, who were violently opposed to the whole idea, made it clear that if he did so he would have to look for a new job. He abandoned the experiment and his model is now in the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. A full scale version based on the model has now been built by the Murdoch Flyer Project.

The Cornish engineer Richard Trevithick began experimenting with high pressure steam and, like Murdoch, first tried out his ideas for a portable form of steam power and for steam transport by building models. This was his third model of 1797 and is now in the Steam Museum at Strafes, Ireland.

One other early designer was Robert Fourness of Otley, who built a curious model steam carriage in 1788. It was a three-wheeled vehicle and had three inverted cylinders that drove a crankshaft. This was connected to the axle by spur gearing, but only one of the driving wheels was keyed to the main axle in order to make it easier to get round sharp bends. The exhaust steam was passed into a tank to preheat the feedwater for the boiler and water could be supplied by a feed pump, worked by a crosshead from one of the piston rods. There is no evidence that it ever reached beyond the model stage, although as Fourness was a successful engineer with his own works, first in Sheffield then in Gainsborough, there would have been nothing to prevent him constructing working machines. However, we have no information on the fate of the prototype and Fourness himself died at an early age. It was to be more than a decade before an actual full-scale engine would be built. It was left to one of the pirates who had plagued Boulton & Watt for many years to take developments much further.

Richard Trevithick was born into a Cornish mining family, and his father was one of a number of engineers who had developed improvements to the old Newcomen engines – and the son saw no reason why he should not do the same to a Boulton & Watt. The fact that this was strictly forbidden did not prevent his trying and, inevitably, he found himself served with an injunction, prohibiting further attempts at piracy of the patent. But the law could not stop him thinking about the problem. The main feature of the Boulton & Watt engine was the separate condenser, but Trevithick wondered what would happen if, instead of condensing the exhaust steam, you simply let it blow away into the atmosphere. He consulted a scientific friend, Davies Gilbert, and asked him how much pressure would be lost if he raised steam pressure to several atmospheres and did not use the condenser. The answer was simple: one atmosphere. Atmospheric pressure at sea level is roughly 15 pounds per square inch (psi). Gilbert reported that ‘he never saw a man more delighted’. Trevithick decided that he could use high pressure steam to produce a new kind of whim engine – the machine used to wind men and materials up and down the shaft. His workshop was his kitchen table and he set about building a model, which was given a ceremonial trial. The honour of stoking the ‘strong iron kettle’ went to Davies Gilbert, and the honour of opening the steam cock went to Lady de Dunstanville, of a prominent mine owning family. The experiment was a success, and Trevithick set about designing a boiler that could safely produce steam at 50psi, more than enough to compensate for the loss of one atmosphere. Earlier boilers had been little better than oversized kettles, but this was a new type, in which the heat was supplied by hot gases from the firebox passing through the water in a tube attached to the chimney. He improved the system, doubling the area in contact with the water, by bending the tube into a U-shape. Davies Gilbert, having provided him with the information on atmospheric pressure, now came to inspect the new boiler:

In 1801 Trevithick built his first full-sized road locomotive, which ran with great success at Camborne, Cornwall on Christmas Eve of that year. In the New Year, he and a friend set out for Tehidy House to show the engine off to Lord and Lady de Dunstanville. They never arrived, having turned over in a ditch, where the engine was abandoned and later caught fire. This working replica, built by the Trevithick Society to celebrate the bicentenary, did however make it and the photograph shows it outside Tehidy House.

‘The boiler was of Cast Iron and its upper surface flat, the Fuel being applied within the Boiler in wrought iron Tubes. We stood near the boiler, i.e. not upon it. When I came deliberately to calculate the Pressure exerted on the Flat surface of Iron, I drew the conclusion that perhaps I had never been in such imminent danger.’

In spite of Gilbert’s qualms, the boiler proved to be safe, and opened up new possibilities. Trevithick realised that his engines need no longer be rooted to the spot; he did not have to build bigger engines to produce more power, simply increase steam pressure.

The next stage was to produce a high-pressure engine mounted on wheels that could be towed along to wherever it was needed. He used a round boiler with an internal flue, that produced steam at about 50psi. The hot gases passed from the firebox, through a U-tube to arrive at the chimney next to the firebox. The exhaust steam from the single cylinder was released through a blast pipe into the chimney, which effectively drew air through the fire. Blast-pipe exhaust would be reinvented a quarter of a century later when Robert Stephenson came to design the famous railway locomotive Rocket. Because exhaust steam puffed out at every stroke of the piston, the engines became known as ‘Puffers’. The next stage seems obvious now, what if the puffer, instead of working machinery, was used to turn the wheels on which it was mounted? Would that enable it to move itself along? Trevithick conducted a very basic experiment to see if the friction between wheel and ground was sufficient for movement, by turning the wheels of a cart by hand and seeing that it did indeed move. That was all he needed to decide that he would build a steam engine that would move itself, a road locomotive. Once again, a model was built and tried, and only then was he ready to build a full-scale road engine.

In 1801 he designed his first steam road carriage. The boiler and cylinder were cast at the engineering works owned by his father-in-law, Henry Harvey, special parts such as valves were made at the workshop of his friend Andrew Harvey and assembly was the work of a local blacksmith Jonathan Tyack. A contemporary account by a man, known only as ‘old Stephen Williams’ describes the first outing at Camborne:

‘In the year 1801, upon Christmas-eve, coming on evening, Captain Dick [Trevithick] got up steam, out in the high-road, we jumped on as many as could, may be seven or eight of us. ’T’was a stiffish hill going from the Wath up to Camborne Beacon, but she went off like a little bird.

‘When she had gone about a quarter of a mile, there was a roughish piece of road covered with loose stones; she didn’t go quite so fast, and as it was a flood of rain, and we were very squeezed together, I jumped off. She was going faster than I could walk, and they went up the hill about a quarter or half a mile farther, when they turned her and came back again.’

The actual details of the engine are not accurately known, but at least the overall p...