- 209 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

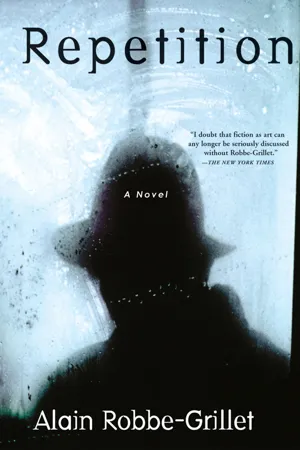

From the French master of the avant-garde:

"A spy tale whose prime puzzle lies in the philosophical intricacies of its own construction" (

Entertainment Weekly

).

We are in the bombed-out Berlin of 1949, after the Second World War, rendered with an atmosphere reminiscent of Orson Welles' The Third Man. Henri Robin, a special agent of the French secret service, arrives in the ruined former capital to which he feels linked by a vague but recurrent childhood memory. But the real purpose of his mission has not been revealed to him, for his superiors have decided to afford him only as much information as is indispensable for the action expected of his blind loyalty. But nothing is what it seems, and matters do not turn out as anticipated . . .

"Exhibits a sensibility as nervous and contemporary—not to mention witty—as that of any novelist working today." — The Los Angeles Times

"Mirrors, doubles, double agents, repetitions, trompe l'oeil war paintings, dream sequences, sexual torture, a criminal mafia of postwar Nazis and murky memories add to the disquieting, disorienting literary puzzle." — San Francisco Chronicle

"A Gothic masterpiece . . . Repetition is fearfest like no other, and a rewarding text that demands to be reread again and again. The master hasn't lost his touch." — The Avon Grove Sun

We are in the bombed-out Berlin of 1949, after the Second World War, rendered with an atmosphere reminiscent of Orson Welles' The Third Man. Henri Robin, a special agent of the French secret service, arrives in the ruined former capital to which he feels linked by a vague but recurrent childhood memory. But the real purpose of his mission has not been revealed to him, for his superiors have decided to afford him only as much information as is indispensable for the action expected of his blind loyalty. But nothing is what it seems, and matters do not turn out as anticipated . . .

"Exhibits a sensibility as nervous and contemporary—not to mention witty—as that of any novelist working today." — The Los Angeles Times

"Mirrors, doubles, double agents, repetitions, trompe l'oeil war paintings, dream sequences, sexual torture, a criminal mafia of postwar Nazis and murky memories add to the disquieting, disorienting literary puzzle." — San Francisco Chronicle

"A Gothic masterpiece . . . Repetition is fearfest like no other, and a rewarding text that demands to be reread again and again. The master hasn't lost his touch." — The Avon Grove Sun

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Third Day

HR awakens in an unknown bedroom which must be a children’s room, given the miniature size of the twin beds, the night tables, the toilet table with its double complement of thick porcelain bowls painted with a grayish design. He himself is lying on a bare mattress, though of adult dimensions, placed directly on the floor. There is also a big traditional mirrored armoire, its heavy door ajar, looking gigantic in this room of doll furniture. Over his head, the electric light is on: a cup-shaped translucent ceiling fixture representing a woman’s face completely surrounded by long undulating serpentine locks, like a sun’s rays. But so bright is the harsh light that he cannot explore the details any further. On the striped wallpaper facing his mattress hangs an academic painting, a vague imitation of Delacroix or Géricault, with nothing remarkable about it save its huge size and mediocre quality.

In the big beveled mirror of the armoire appears the reflection of the wide-open bedroom door. In the doorway, and against the dark background of the hallway, stands Gigi, staring at the traveler lying on his mattress. Since he habitually sleeps on his right side, he sees the girl only by means of her reflection in the armoire mirror—twice removed, it would seem, in a very calculated fashion. Yet the young visitor is staring directly at the bottom of the red curtains and the bolster, without glancing at the armoire mirror, so that she cannot know if the sleeper has his eyes open now, watching her, and speculating further about this strange child. Why does this active little creature remain silent and motionless, keeping watch so attentively over the guest’s troubling repose? Is there something abnormal about such sleep; is it too sound, is it lasting too long? Has some physician, summoned by an emergency call, already attempted to rouse the man? Is there a sort of anguish to be discerned on the child’s pretty face?

The evocation of a doctor possibly being at his bedside suddenly wakens in HR’s troubled mind a fragile and fragmentary memory from his immediate past. A man with a bald skull, a Lenin goatee, and steel-rimmed glasses, holding a notepad and pen, was sitting on a chair at the foot of the mattress, while he himself, his eyes on the ceiling, talked on and on, but in a hoarse, unrecognizable voice, without managing to control what he was saying. What could he be telling in his delirium? Now and then he cast a terrified glance at his impassive examiner, behind whom was standing another man, smiling for no evident reason. And this latter man curiously resembled HR himself, the more so because he had put on the suit and the fur-lined jacket in which the special agent had arrived in Berlin.

And now this false HR, whose face remained quite identifiable despite his obviously artificial mustache, has leaned toward the recording physician to whisper something in his ear, while showing him a passage in a bundle of manuscript pages.… The image freezes for a few seconds in the incontestable density of the real, and then collapses with disconcerting speed. Scarcely a minute later, the whole phantasmal sequence has vanished, dissolved in the mist, completely unreal. Doubtless there was nothing more to it than the drifting residue of a dream fragment.

Today Gigi is wearing a navy-blue schoolgirl’s dress, pretty enough though reminiscent of the severe costume of religious boarding schools with its short pleated skirt, its white socks, and its demure white collar. And now she’s moving quite decisively, though gracefully too, toward the mirrored armoire, as if she had just discovered its inopportune (or else henceforth useless) opening. With a careful gesture she closes the door, its rusty hinges creaking for several seconds. HR pretends to waken with a start because of the noise; he hurriedly readjusts the buttons of the pajamas that someone has put on him (who? when? why?) and abruptly sits up. As casually as possible, despite a persistent uncer tainty about just where he is and the reasons that have led to his sleeping here, he says: “Hello, little girl!”

The child responds by no more than a toss of her head. She seems preoccupied, perhaps upset. As a matter of fact, her behavior is so different from that of the day before (but was it the day before?) that she might be an altogether different girl, though physically identical with the first one. The bewildered traveler risks a neutral question, offered in an indifferent tone of voice: “Are you off to school, dear?”

“No, why?” she asks in a sulky, surprised tone of voice. “I’ve been through with my courses and homework and tests for a long time.… Besides, you don’t have to call me ‘dear.’”

“Whatever you like.… I guess I was influenced by what you’re wearing.”

“What’s that got to do with it? These are my working clothes. Besides, no one goes to school in the middle of the night.”

While Gigi stares at herself in the armoire mirror, methodically passing her entire person in review, from the blond curls she ruffles quite knowingly to the white socks she pushes a little farther down on her ankles, HR, as if such scrutiny were contagious, stands up to inspect his own exhausted face, bending far over toward one of the two toilet mirrors, placed too low for easy examination, above the porcelain bowls. His borrowed sky-blue striped pajamas have the letter W embroidered on the left breast pocket. Without seeming to attach much importance to the question, he asks: “What kind of work?”

“Dance hostess.”

“At your age? In that dress?”

“There’s no particular age for work like that, as you ought to know, Monsieur Frenchman. As far as the dress goes, it’s compulsory in the cabaret where I’m a waitress, among other things.… It reminds the German officers of their absent families!”

HR has turned toward the promising nymph, who takes advantage of this movement to emphasize the irony of her observation by a naughty wink, behind a lock of hair that has fallen over one eyelid and her cheek. Her indecent gesture seems all the more suggestive in that the young lady has tucked up to her waist her full skirt, with its carefully pressed pleats, in order to adjust in front of the mirror her rather too loose panties, being careful not to let the appropriate gaps disappear. Her bare legs are smooth and suntanned all the way to the top of her thighs, as if this were still high summer at the beach. He asks: “Who’s this W whose pajamas I’m wearing?”

“Walther, of course!”

“And who’s Walther?”

“Walther von Brücke, my half-brother. You saw him yesterday in the vacation photograph, the one at the seashore in the salon downstairs.”

“Does he live here?”

“Of course not! Thank God! The house had been empty and closed for a long time when Io moved in, at the end of ’46. That donkey Walther had to get himself killed as a hero on the Russian front during the German retreat.10 Or else he’s rotting in a camp somewhere in the wilds of Siberia.”

Note 10 – Unpleasant to her colleagues whenever she has the chance, our budding trollop employs her customary effrontery here. And merely for the gratuitous pleasure of lying, for no Service directive provided this absurd detail, all too easy to refute.

Gigi, who has meanwhile reopened the creaking door of the big armoire, only half of which is fitted out as a closet, now searches frantically among the clothes, lingerie, and trinkets heaped up in great confusion on the shelves, apparently looking for some little object she fails to find. A belt? A handkerchief? A piece of costume jewelry? In her exasperation she drops on the floor a delicate high-heeled black slipper whose triangular vamp is entirely covered with blue sequins. HR asks if she has lost something, but she doesn’t bother to reply. Yet she must have laid her hand on what she was looking for, some very discreet accessory of an unimaginable nature, for when she closes the armoire again and turns back toward him it is with, quite suddenly, her first smile. He asks: “If I’m not mistaken, I’m using your room?”

“No, not really. You saw the size of the beds! But it’s the only mirror in the house where you can see yourself from head to toe.… Besides, it used to be my room, in the old days … practically from birth, until 1940. … I was five. I used to play I was two people, because of the two beds and the two bowls. Some days I was W, and others I was M. Though they were twins, they must have been quite different from each other. I made up special habits for each of them, and very marked characters, personal peculiarities, notions, and ways of behaving that were totally opposed to each other. …I was careful to respect the imaginary identity of each one.”

“What’s become of M?”

“Nothing. Markus von Brücke died when he was very young.… Would you like me to open the curtains?”

“Why bother. Didn’t you say it was a dark night?”

“It doesn’t matter. You’ll see! There’s no window anyway.…”

Having regained her juvenile exuberance for no obvious reason, the girl takes three elastic leaps over the blue-striped mattress, crossing the space separating the mirrored armoire from the closely drawn curtains, which she slides with both hands in opposite directions across their gilded metal rod, the wooden rings dividing the curtains right and left with a loud clicking noise, as though to make room, in their median separation, for the expected stage of a theater. But behind the heavy curtains there is nothing but the wall.

This wall, as a matter of fact, contains no sort of bay or window in the old style, nor the slightest opening of any kind, except in trompe l’oeil: a painted window frame looking out on an imaginary exterior, both painted on the plaster with an amazing effect of tangible presence, accentuated by tiny spotlights ingeniously arranged so that the gesture of opening the curtains must have turned them on. Framed by a classic French window, the wood of which was rep resented with hypertrophic realism, the molding showing every last scratch or defect in the grain, its iron bolt rusted in places, and beyond the twelve rectangular panes (two rows of three in each “door”) appears a ruined landscape of war. Dead or dying men lie here and there among the rubble, wearing the greenish, easily identifiable uniforms of the Wehrmacht. Most have lost their helmets. A column of disarmed prisoners, in the same more or less ragged and filthy uniforms, vanishes into the distance to the right, guarded by Russian soldiers covering them with the short barrels of their automatic assault rifles.

In the foreground, life-size and so close that he seems two steps away from the house, staggers a wounded noncommissioned officer, also a German, blinded by a hastily improvised bandage around his head from ear to ear, stained red over his eyes. Moreover, some blood has trickled under this bandage and around his nostrils down to his mustache. His right hand, held out in front of his face, fingers spread wide, seems to beat the air ahead of him for fear of some possible obstacle. And yet a blond girl of thirteen or fourteen, dressed like a little Ukrainian or Bulgarian peasant, is holding his left hand to guide him, or more precisely to pull him toward that improbable and providential window which she has been struggling to reach since the beginning of time, her free (left) hand extended toward the miraculously intact panes, where she is about to knock in the hope of finding some help, some refuge in any case, not so much for herself as for this blind man she has taken charge of, God knows with what obscure intentions.… Upon closer consideration, it appears that this charitable child distinctly resembles Gigi. In her exertions, she has lost the bright-colored cloth which in normal circumstances would cover her head. The golden locks flutter around her head, her features excited by this bold course through unknown perils.… After a long silence, she murmurs in an incredulous tone of voice, as if she can scarcely admit the existence of the picture:

“It must have been Walther who painted that crazy thing, to take his mind off … everything.”

“And there was no real window in the children’s room?”

“Yes, of course there was! … Overlooking the back garden, there were even some big trees … and goats. It must have been walled up later, for unknown reasons, probably at the very beginning of the siege of Berlin. Io says the mural was painted during the final battle by my half-brother, who was caught here on his last leave.”11

In the distance, to the left, appear several ruined monuments recalling ancient Greece, with a series of columns broken at various heights, a gaping portico, fragments of architraves and fallen capitals. A strayed black kid-goat has climbed up on one of these heaps, as if to contemplate the historical situation. If the artist has sought to represent a specific episode (a personal recollection or a story told by a comrade) of World War II, it might concern the Soviet offensive in Macedonia during December 1944. Dark clouds spread in long parallel strips above the hills. The carcass of a destroyed tank aims its huge useless cannon at the sky. A grove of pine trees apparently keeps the Russian troops from seeing our two fugitives, with whom of course I identify myself on account of my present tribulations, actually discovering in the man’s features and physique a certain resemblance to my own.

Note 11 – The unpredictable Guégué, for once in her life, is not making something up but accurately reporting some correct information furnished by her mother. Except for one detail: I had not reached the banks of the Spree on leave, which would scarcely have been conceivable in the spring of ’45, but on the contrary on a highly dangerous “special contact mission,” which the Russo-Polish offensive, launched on April 22, immediately rendered null and void. Unfortunately or fortunately, who can ever say? Note as well—and it is anything but surprising—that the girl doesn’t seem at all concerned about a certain incoherence in her remarks: if I am in Berlin during the final assault, I can hardly be dead a few months earlier, during rearguard skirmishes in the Ukraine, Byelorussia, or Poland, as she appeared to believe likely a few moments earlier.

As for the presence of Greek ruins on the distant hills remarked by the narrator, this was merely—if I remember correctly—a sort of mirror image of those already appearing in the big allegorical scene which, from my earliest childhood, hung on the opposite wall of this children’s room. It might also be a reference, though, or an unconscious homage to the painter Lovis Corinth, whose work once had a strong influence on my own, almost as much, I suspect, as that of Caspar David Friedrich, who struggled all his life on the island of Rügen to express what David d’Angers calls “the tragedy of landscape.” But the style adopted for the mural in question doesn’t have much to do with either one, except maybe for the latter’s dramatic skies; what mattered for me was to portray in the minutest detail an authentic and personal image of war, directly from the front.

Reference to my beloved Friedrich leads me to correct an incomprehensible error (unless, once again, this was an intentional falsification for an obscure motive) committed by the so-called Henri Robin concerning the geological nature of the soil on the German coast of the Baltic. Caspar David Friedrich, as a matter of fact, has produced countless canvases representing the sparkling marble, or more prosaically the luminous white chalk cliffs which have made Rügen so famous. That our scrupulous chronicler should have retained the memory of enormous blocks of granite, resembling the Armorican boulders of his childhood, quite bewilders me, the more so since his solid agronomist’s training, which he deliberately mentions (or even parades, some say), should have kept him from falling into this unlikely confusion; in this northern region, the old Hercynian shelf never extends beyond the overwhelming Harz massif, where moreover so many Celtic and Germanic legends are to be met with: the magical forest of the Perthes, which is another Brocéliande, and the young witches of the Walpurgisnacht.

Among these, the one who concerns us now, and whom we designate in our messages by the code name GG (or else 2G), might be the worst kind, one of the unreal legion of barely nubile flower maidens in the power of the Arthuro-Wagnerian wizard Klingsor. While attempting to keep her under control, I must for the sake of the cause pretend to submit to her almost daily extravagances and indulge her in whims of which I might gradually become the accomplice, without being entirely conscious of a spell which would inexorably lead me to a perhaps imminent death … or worse still, to loss of willpower and madness.…

Already I wonder if it is really an accident that she happened to be on my path. I was prowling that day around Father’s house, where I had not set foot since the surrender. I knew that Dany had returned to Berlin but was staying somewhere else, probably in the Russian zone, more or less clandestinely, and that Jo, his second wife, whom he had to repudiate in 1940, had just taken up residence on the premises with the blessing of the American Secret Service. Rigged out with a false mustache and big dark glasses, which on principle I wear on days that are too bright (to protect my eyes, still delicate ever since my wound of October ’44 in Transylvania), with a broad-brimmed hat pulled down over my forehead, I ran no risk of being recognized by my young mother-in-law (she’s fifteen years younger than I), if she had taken it into her head to come outside at that very moment. Standing in front of the open door, I pretended to be interested in the varnished wood panel of recent manufacture, decorated with elegant hand-painted scrollwork meant to reproduce the 1900-type hardware that constituted the old fence, as if I just happened to be looking for dolls, or else had some to sell, a supposition which would not, in a sense, have been entirely mistaken.

Then, looking up toward the still-appealing family villa, I was astonished to discover (how could I have failed to notice it when I arrived?) that just above the door, with its high rectangular spy hole, its glass protected by massive cast-iron arabesques, the central window upstairs was wide open, which was hardly unusual in this warm autumn day. In the open space was standing a feminine figure which at first I took for a shop-window mannequin, so perfect did her immobility seem, at that distance, the hypothesis of such a display, boldly facing the street, seeming moreover quite likely, given the commercial nature of the premises advertised on the wooden panel serving as a signboard. As for the type of life-size doll selected to lure the customer (a slender adolescent girl with blond curls in suggestive disarray, presented in an outrageously transparent outfit, permitting, no, insisting on the attraction of her promising girlish charms), it could only reinforce the equivocal—not to say prostitutional—character of the handwritten sign, the traffic in minors for sexual purposes likely to be, in today’s ruined Berlin, much more widespread than that of children’s toys or wax figures for fashionable shops.

After carefully verifying one lexical detail referring to the sign’s possible implications, I looked up toward the second floor.… The image had changed. It was no longer an erotic effigy from some wax museum whose budding attractions were exhibited at the window, but indeed a very young girl, very much alive, wriggling there in a fashion as excessive as it was incomprehensible, leaning forward over the railing with her transparent slip clinging now to just one shoulder, the already- loosened straps gradually coming undone. Yet even her most extreme gestures and attitudes retained a strange grace which suggested some delirious Cambodian Apsaras undulating her six arms in all directions, her slender waist rippling as delicately as her swanlike neck. Her reddish gold head of hair, illuminated by t...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Prologue

- First Day

- Second Day

- Third Day

- Fourth Day

- Fifth Day

- Epilogue

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Repetition by Alain Robbe-Grillet, Richard Howard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literatura & Literatura general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.