![]()

1

Censored Origins

The Loeb Classical Library publishes editions of the Greek and Roman classics that have shaped so much of Western culture. Each of their books includes the original language alongside an English translation and—because they are widely used in schools and universities—their early editors faced a rather delicate problem; some of these classics contained passages that were deemed (at least in the early twentieth century when the series began) to be unsuitable for impressionable young minds. Take the Athenian comedian Aristophanes, for example. His celebrated play Lysistrata (or the “army-disbander”) is about the women of Athens and Sparta trying to put an end to the endless wars between their cities. They hit on the simple but effective strategy of denying their men sex until they stop fighting. This leads to a wonderfully bawdy scene when the men finally meet to negotiate; each is unable to assuage the permanent erection he has acquired as a result of his enforced abstinence. The text is full of lewd puns and double-entendres whose meanings would have been made unmistakable by the Ancient Greek actors’ costumes, which frequently featured gigantic fake penises. What was a respectable publishing house to do with such material?

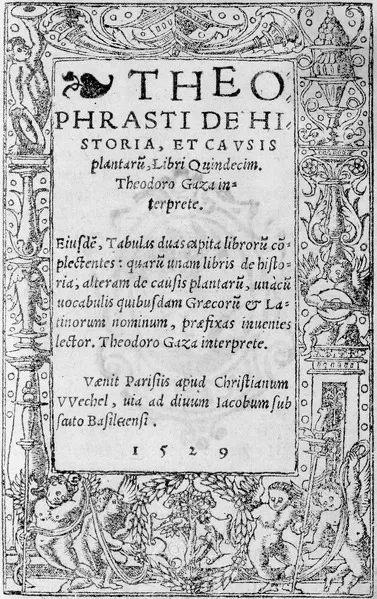

The publisher’s solution for material like that in Lysistrata was simply to leave the offending passages in the original Latin or Greek (thus providing generations of young students with an additional incentive to master these ancient languages). However, concealed beneath the modest green and red covers of the Loeb library there is one exception to this rule. Amid the numerous tales of rape, incest, orgies, and debauchery, only one passage was considered so unsuitable as to be omitted altogether. When Sir Arthur Hort edited the Loeb edition of Theophrastus’s Historia Plantarum (Enquiry into Plants), he dropped the passage “On Aphrodisiacs and Sexual Drugs” (IX.18.3–IX.18.11); not only was there no translation—even the Greek was excised. This appears to be the only such omission in the more than 500 volumes of Loeb and the decision must have been taken quite late in the publication process, because the book retains an enigmatic index entry to one of the missing aphrodisiac plants, an orchid.1

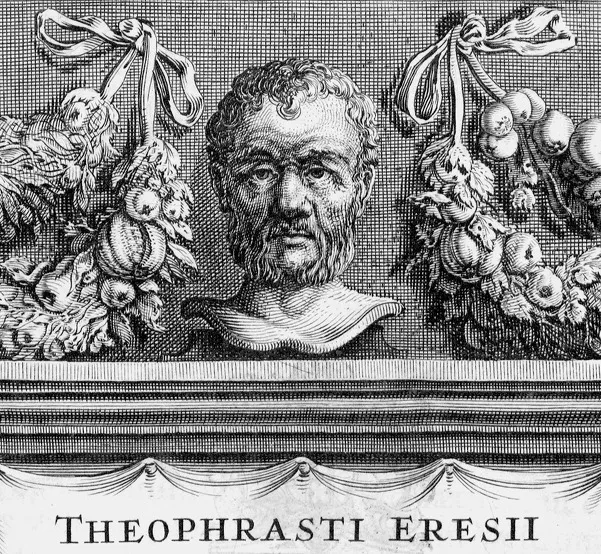

To understand the sexy orchid’s place in Western culture, we have to begin (as we do with so many other aspects of our science, culture, medicine, and mythology) in Ancient Greece. The Western traditions of understanding living things originated on the shores of the Mediterranean; for animals, we turn to Aristotle, but for plants, we turn to his friend and successor, Theophrastus of Eresus (ca. 371–ca. 287 BCE), universally acknowledged as the “father of botany.” The title sounds like quite an honor, especially if you are remembered more than 2,000 years after your death, yet Theophrastus might well be disappointed if he were able to know of his fame. Although he clearly loved and was fascinated by plants, for him they were merely one among many studies. He was a pupil of both Plato and Aristotle (who described him as “a man of extraordinary acuteness, who could both comprehend and explain everything”).2

The ninth book of Theophrastus’ Enquiry into Plants is a surprising text to be the target of censorship, since it’s the world’s earliest surviving Greek herbal and provides a unique insight into the Ancient Greeks’ knowledge of plants and their uses. In amongst many other topics, Theophrastus comments that, “Besides affecting health, disease and death, people say that some plants have other specific effects, physical and mental. Firstly, the physical effects, by which I mean favouring or inhibiting procreation”:

There is at least one plant whose root is said to show both powers. This is the so-called salep, which has a double bulb, one large and one small. The larger, given in the milk of a mountain goat, produces more vigour in sexual intercourse; the smaller inhibits and forestalls.3

In this short passage, the orchid made its debut in Western science; “salep” is a kind of nutritious porridge, still widely consumed in parts of the Middle East, that is made from what are often called the bulbs of orchids (they are really tubers or rhizomes), such as the Early Purple orchid (Orchis mascula). The tubers contain stored starch (the larger and smoother tuber is formed by the current year’s leaves; the other is last year’s, becoming smaller and wrinkled as its food supply is used).4 Thanks to Theophrastus’ decision to record this folk myth about the plant’s aphrodisiac properties, orchids were associated with sex from the first moment they appeared in Western writing and the link has never been broken.

Theophrastus did not coin the name orchis (from which the modern name, orchid, is derived); it—along with the information about its aphrodisiac properties—came from the root-cutters, or “rhizotomai,” a group of now-nameless herbalists who were experts in the culinary and medicinal uses of roots (in modern usage, a rhizome is an underground plant stem, but the word has often been used informally to mean a root). The Ancient Greeks knew of a handful of species of orchids, all of which grew around the Mediterranean. As we have seen, in order to survive the semi-drought of summer these species had underground storage organs, which botanists describe as paired “globose tubers,” but which everyone else, from the ancient world onward, recognized as resembling a pair of testicles. (An early name for one of these plants was Cynosorchis, which translates, rather directly, as “dog’s bollocks.”)

The Lesbian Boy

Theophrastus was born in Eresus on the island of Lesbos and is therefore sometimes known—rather confusingly to modern readers—as the Lesbian Boy. In the ancient world, Lesbos was famous for “the excellent quality of its products, material, artistic, and intellectual”; for generations, Greeks and Romans who wanted to bestow the highest possible praise on anything, “whether it were a piece of music, a verse of poetry, or a cask of wine, were accustomed to pronounce it Lesbian.”5 His original name was Tyrtamus and at a very young age he went to Athens to study at Plato’s Academy. Tyrtamus was only 21 when Plato died and Aristotle (Plato’s former pupil) inherited the Academy; it was Aristotle who renamed his friend, and former fellow-pupil, Theophrastus for the “divine character of his eloquence.”6

According to his first biographer, Theophrastus wrote more than 220 books, containing over two million words.7 They ranged across the whole of the wide and unpredictable terrain of Ancient Greek philosophy. Among Theophrastus’ interests was the nature of knowledge itself, the branch of philosophy called epistemology; he wrote a book that asked “What are the Different Manners of Acquiring Knowledge” (as well as “three on Telling Lies”). In addition to what we would still consider basic philosophy, Theophrastus wrote books on Epilepsy, Enthusiasm, and Empedocles. Not to mention “three books of Objections” (a branch of philosophy now mainly practiced by nine-year-olds). His eclectic oeuvre included a book “on Mistaken Pleasures” and one (presumably the antidote to the first) “on Pleasure according to the Definition of Aristotle.”

However, for a Greek philosopher, knowledge (a word we get from the Greek gno, γνω) could not be contained by the kinds of modern boundaries that are created and policed by disciplinary specialists and their categories. Unhindered by any consideration of which university faculty he might belong to, or in which peer-refereed journal he might publish, Theophrastus wrote a book “on Smells” and well as “one on Wine and Oil,” to say nothing of “one on Hair; one on Tyranny; three on Water; one on Sleep and Dreams; three on Friendship; two on Liberality” and “three on Nature.”8 And when it came to the branches of philosophy that we would now call biology (a term that would not be coined for another 2,000 years), the Lesbian boy was equally prolific, contributing a book “on the Difference of the Voices of Similar Animals; one on Sudden Appearances; one on Animals which Bite or Sting; one on such Animals as are said to be Jealous” and—just to make sure his work was really comprehensive—“seven on Animals in General.”

Despite this extraordinary output, only a tiny percentage of Theophrastus’ work survives, mainly fragments of his botanical works, yet they are more than sufficient to secure him the title of the world’s first botanist. Two thousand years before the terms were coined, Theophrastus identified the most profound division within the plant world, that between dicotyledons (or dicots, plants with two embryonic leaves enfolded in their seeds) and monocotyledons (or monocots, those with a single seed leaf—the group that includes orchids). He described the anatomy of plants in great detail, as well as the geographical distribution of many species, he specified their medicinal and culinary properties, including their magical and aphrodisiac properties, and he even explained how to cultivate them. His knowledge was based on careful studies conducted in the garden attached to the Athenian academy (he owned at least ten slaves who gardened for him; in his will he gave some their freedom and specified that the others were to be freed when they had worked long enough).

To understand why Theophrastus deserves his place in history, consider the titles of his botanical books: the Enquiry into Plants and the Causes of Plants. The idea that plants and animals had causes was a new one. As far as we can tell from the very fragmentary evidence, the writers of earlier plant treatises were interested only in the uses of plants; their works were agricultural, horticultural, or medical. Although Aristotle and Theophrastus continued this tradition, they also studied living things for their own sake and they were sometimes mocked for “going about the country picking up and curiously peering into the least little things of nature, such as were of no possible use.” Near the start of Theophrastus’ Enquiry he lists the external and obvious organs of a plant such as a tree: root, stem, branch, bud, leaf, flower, and fruit. There is a logic here that is driven by curiosity, a sense that the plant no longer is a means to an end, but has become an object of interest in its own right.9

Although the origins of modern botany are discernible in the ancient world, we have to be careful not to separate out the knowledge that we now take seriously from all the other ways the Greeks understood plants. It is clear that Theophrastus was building on the work of earlier medicinal writers and that he shared their interest in the practical benefits people could derive from plants. The fact that his list of the plant’s parts begins with roots is evidence of his debt to the earlier rhizotomai, who were obsessed with the secret, subterranean powers of roots; the mandrake that could drive you mad, and the orchid’s tubers that could promote or suppress lust. Theophrastus built on this complex mixture of folk myth and practical wisdom—often accepting, occasionally questioning—but he added a rationale for the structure of his list, which was simply that “in all plants the growth of the root precedes that of the superior parts” (Enquiry, Book I, chapter 2). The story of the orchid begins with Theophrastus’ account of its parts and their uses, but the orchid’s story is part of a much wider one—that of the long, slow death of Greek philosophy. Over the next two millennia, one subject after another would be detached from the original body of knowledge; today philosophers are left to dream of far fewer things in heaven and earth than their Greek predecessors. Philosophers like Aristotle and Theophrastus took the world and everything in it, on it, below it, and above it as their object of study, from the nature of the heavens to the nature of friendship, from the birth of the cosmos to that of an insect. Their successors were to spend centuries retreating into narrower and narrower provinces of knowledge, each with its own narrowly defined set of answers to the question “What are the Different Manners of Acquiring Knowledge.” But it was from among these increasingly parochial enterprises that today’s sciences emerged, giving us the power to answer questions that Theophrastus and Aristotle could barely have dreamt of asking.

The Uses of Orchids

When, in the ninth book of his Enquiry, Theophrastus turned to the uses of plants as pharmaka (medicines), he recorded the apparently contradictory claim that orchids both promoted erections and caused impotence (given the orchids’ similarity to testicles, it is unsurprising that female desire was not considered, yet this was an oversight male inquirers were to persevere with for many centuries). He noted that it seems surprising that a single plant should have both properties, but was convinced that “it is not absurd that there should be...