- 443 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"A sprawling account of New York lives under the long shadow of AIDS, it deals beautifully with the drugs that save us and the drugs that don't."—

The Guardian (Best Books of the Year)

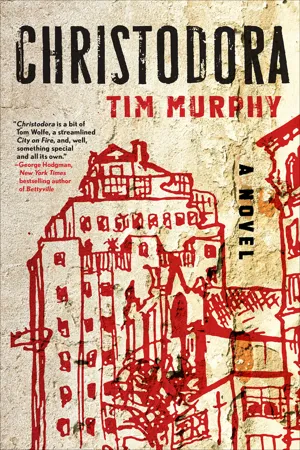

In this vivid and compelling novel, Tim Murphy follows a diverse set of characters whose fates intertwine in an iconic building in Manhattan's East Village, the Christodora. The Christodora is home to Milly and Jared, a privileged young couple with artistic ambitions. Their neighbor, Hector, a Puerto Rican gay man who was once a celebrated AIDS activist but is now a lonely addict, becomes connected to Milly and Jared's lives in ways none of them can anticipate. Meanwhile, Milly and Jared's adopted son Mateo grows to see the opportunity for both self-realization and oblivion that New York offers.

As the junkies and protestors of the 1980s give way to the hipsters of the 2000s and they, in turn, to the wealthy residents of the crowded, glass-towered city of the 2020s, enormous changes rock the personal lives of Milly and Jared and the constellation of people around them. Moving kaleidoscopically from the Tompkins Square Riots and attempts by activists to galvanize a true response to the AIDS epidemic, to the New York City of the future, Christodora recounts the heartbreak wrought by AIDS, illustrates the allure and destructive power of hard drugs, and brings to life the ever-changing city itself.

"A rich and complicated New York saga . . . Christodora has the scope of other New York epics, such as Bonfire of the Vanities, The Goldfinch and City on Fire."— Newsday

In this vivid and compelling novel, Tim Murphy follows a diverse set of characters whose fates intertwine in an iconic building in Manhattan's East Village, the Christodora. The Christodora is home to Milly and Jared, a privileged young couple with artistic ambitions. Their neighbor, Hector, a Puerto Rican gay man who was once a celebrated AIDS activist but is now a lonely addict, becomes connected to Milly and Jared's lives in ways none of them can anticipate. Meanwhile, Milly and Jared's adopted son Mateo grows to see the opportunity for both self-realization and oblivion that New York offers.

As the junkies and protestors of the 1980s give way to the hipsters of the 2000s and they, in turn, to the wealthy residents of the crowded, glass-towered city of the 2020s, enormous changes rock the personal lives of Milly and Jared and the constellation of people around them. Moving kaleidoscopically from the Tompkins Square Riots and attempts by activists to galvanize a true response to the AIDS epidemic, to the New York City of the future, Christodora recounts the heartbreak wrought by AIDS, illustrates the allure and destructive power of hard drugs, and brings to life the ever-changing city itself.

"A rich and complicated New York saga . . . Christodora has the scope of other New York epics, such as Bonfire of the Vanities, The Goldfinch and City on Fire."— Newsday

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Urban Dwellers

1981–2010

One

Neighbors and Their Dogs

(2001)

By the time Christodora House settlement erected its handsomely simple new sixteen-story brick tower on the corner of Avenue B and Ninth Street in 1928—an edifice that loomed over Tompkins Square Park and the surrounding blocks of humble tenements—the Traums had long left the Lower East Side. They were part of that first wave of worldly German Jews who had come to New York City in the early or mid-nineteenth century. Those sedate, self-conscious Jews had slowly migrated uptown as the old neighborhood became crowded with their dirt-poor eastern European cousins, Jews who spoke Yiddish and held to embarrassing old traditions, such as separating men and women at temple. Around the time that WASPs were raising money to fund the new Christodora building, which aimed to civilize these shtetl children and their equally wild-haired Catholic immigrant peers, Felix Traum, an investment banker, was already playing a leading role in the building of the new Temple Emanu-El on Fifth Avenue in midtown, a limestone Romanesque pile that would become the most prestigious synagogue in America. Accordingly, Felix had moved his family to the Upper East Side, where they lived in a not-opulent but still very capacious apartment not far from the Ochses of the New York Times.

Felix’s son Steven, not interested in the bald pursuit of money, became an urban planner who, in his quiet way, helped hold back some of the worst excesses of Robert Moses, whose neighborhood-crushing projects stopped short of running a ten-lane expressway across lower Manhattan. Steven was part of that 1960s–1970s generation of planners who were much taken with Jane Jacobs’s The Death and Life of Great American Cities and her idea that the best neighborhoods were small, intimate, and dense. On weekends, Steven would find himself taking his wife, Deanna, also an academic, and their two small children, Stephanie and Jared, down from the Upper East Side to the old neighborhood where his family had first landed in America, inside the humble, semi-derelict synagogues and then to Katz’s Deli for pastrami on rye.

The neighborhood was almost completely Puerto Rican now, full of junkies and homeless people. Half the buildings were abandoned, including the Christodora, which had fallen on hard times. Decades ago, it had become the property of the city, which used it for various municipal purposes until it sold the building in 1975 for about $60,000. Nearly fifty years prior, it had cost $1 million to build. Such were the depths to which the Christodora, which means the “gift of Christ” in Greek had fallen. In that time the country was poised to take a rightward swing under Reagan. But that did not stop Steven Traum from standing before the Christodora’s facade, with its beguiling and eerie neo-Gothic frieze of angels, demons, and goblins set over the door. Steven held the hand of each of his privileged children on either side and dreamed about reviving the old neighborhood.

In the 1980s, the old neighborhood was rebranded the “East Village,” at least above Houston Street. Throughout the decade, the Christodora, still derelict and disused, had changed hands several times, each time for more money, until, in 1986, its destroyed inner plumbing and wiring was properly gutted and renewed and it became a condo conversion—a shocking development that New York magazine, on its cover, heralded as the inevitable triumph of gentrification in a neighborhood long thought of as a sanctuary for wayward bohemians. The Christodora offered rooms with massive ceilings and windows looking out beyond the drug-scarred mayhem of the neighborhood onto the vistas of Manhattan. Steven, friends with a social worker and a journalist who bought in immediately, could not resist and, for the trifling sum of $90,000, purchased a two-bedroom, 1,400-square-foot corner unit on the sixth floor, suffused with light and overlooking the park, which in the evenings became an encampment for homeless people and heroin shooters, its black square of land dotted with ragtag tents and bonfires.

Steven began using the apartment as an office. Deanna thought he was crazy, but Steven was delighted to spend his days down in the old neighborhood, and most afternoons you could find him getting his lunch at Katz’s, or walking back to the Christodora with smoked salmon on a bagel from Russ and Daughters. Sometimes he would turn the corner on Houston onto Norfolk Street and poke his head inside the ornate old Anshe Slonim Synagogue, whose peak-roofed beauty filled his eyes with tears. In time, he met the Spanish artist Angel Orensanz, who had just bought the abandoned old building to use as a studio. Eventually, Orensanz would turn it into a great arts center, keeping its opulence intact and signaling the rebirth of the neighborhood. Such a rebirth moved Steven to a very fine tremble of excitement.

Steven’s daughter, Stephanie, went to college in California and never moved back, but Jared, a handsome, pale-skinned boy who had a mop of curly honey-colored hair and brown eyes that could flash both warmly amused and arrogantly entitled, went to college not far from New York. Even before he graduated, Jared was shacking up during breaks and summers at the Christodora, cultivating a love of the neighborhood that became a quiet bond between him and his father. Jared wanted to move back to New York City and continue making the kind of industrial sculpture he’d started making in college until he was considered the next Richard Serra, so it wasn’t surprising that he became the de facto resident of the apartment at the Christodora, rising some mornings after nights of heavy drinking with friends only when the sound of his father’s key in the lock woke him around eleven o’clock. Father, arriving with two large coffees in hand, got right to work, while son stumbled to the shower and then, clutching his own coffee, pondered just how he should apply the day toward his goal of being a famous artist. Should he go for an MFA immediately? Find some already renowned artist to apprentice with?

“Russ?” he’d call out to his father in the other room, looking up from the New York Times where, in the Arts section, he read with a furrowed brow about the people he wanted to supplant someday.

“Russ,” Steven would call back. “Twenty minutes.”

And in twenty minutes father and son would take the elevator down to the Christodora’s lobby, which was handsome yet very simple, like the Christodora generally, and walk across Tompkins Square Park. It was early 1991, in that short window of time between the 1988 summer riots in the park—in which its longtime homeless denizens and the NYPD phalanxes had faced off amid an atmosphere of increasing rage over gentrification—and the coming May, when the park riots would flare up again briefly and the city would shut the park for renovations until the following year.

Jared had been in the apartment at the Christodora that August night when the riots first broke out. It was 1988, the summer before his freshman year in college. He was drinking and smoking pot with some high school friends, rhapsodizing about the brilliance of the Pixies’ Surfer Rosa, which they were listening to, all of them trying to stay cool amid the heat by hanging out near the open window looking down on the park, which was a scene of mayhem. Police lights whirled in the humid night sky and sirens wailed, crowds of shirtless skinheads massed and surged, indistinct voices projected over loudspeakers and young people charged around with bedsheet signs decrying gentrification. Most of the heavy action was concentrated on the other side of the park, on Avenue A, ...

Table of contents

- CHRISTODORA

- Also by Tim Murphy

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- CHRISTODORA

- Part I: Urban Dwellers (1981-2010)

- Part II: The Left Coast (1992-2012)

- Part III: Grown-Ups (1992-2021)

- Acknowledgments

- Credits

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Christodora by Tim Murphy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literature General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.