![]()

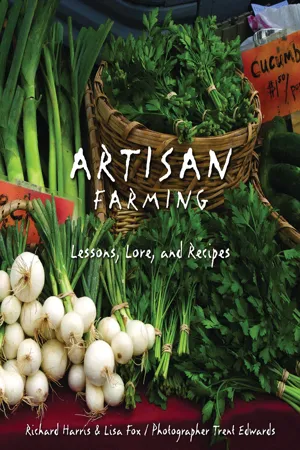

A cornucopia of foods finds its way from New Mexico growers to consumers, mostly through farmers markets, where about three-fourths of all small farm produce is sold. Many of the vegetables offered at farmers markets are exotics and heirlooms; many of the fruits are unusual varieties uniquely adapted to the erratic New Mexico climate. And many of the meats and animal products are unlike anything you’ll find in your local supermarket.

There are also other distinctively New Mexican farm products, such as plum wine and lavender. The array of recipes included in this chapter, some drawn from traditional regional recipes, others from professional chefs and amateur gourmet cooks, are designed to offer quick and easy solutions to the kind of questions that often occur to shoppers at farmers markets, such as, “What can you make with Swiss chard and rhubarb?”

Vegetables

As consumers who make regular weekly stops at their local farmers market quickly discover, part of the pleasure is watching how the harvest changes from week to week, constantly presenting new challenges in cookery.

At the few markets that are open in early spring, shoppers will find plenty of root vegetables such as carrots, garlic, shallots, and potatoes, as well as greens like Swiss chard, spinach, arugula, mustard greens, salad greens, and Chinese greens, which are often grown in greenhouses. As the end of spring approaches and a hot climate replaces the intermittent freezes of March and April, other vegetables appear, especially asparagus, which grows in amazing abundance in the Velarde and Embudo area, but only for a brief time. There are also red and golden beets, cauliflower and broccoli, and kale and young peas. By July, when all farmers markets are open, vegetables appear in the greatest profusion and include cucumbers, summer squash, garlic, beans (green, purple, and yellow), eggplant, and tomatoes, as well as sweet peppers and corn. The pungent smell of roasting green chile calls to shoppers during the fall harvest, when the farmers markets also offer up such exotica as edamame, daikon, kohlrabi, and leeks, as well as unbelievably large cabbages.

Vegetable farmers you may meet at New Mexico’s farmers markets are as diverse as the bounty of their fields.

Matt Romero , an Española native, left his profession at age forty-two as chef at the Ohkay Owingeh casino to take over operation of a ten-acre Velarde farm belonging to his wife Emily’s grandmother. Although Matt’s mother had also grown up on a northern New Mexico farm, she had hated it and passed her distaste along to Matt at an early age. “I couldn’t even grow a garden,” he recalls in a recent Santa Fe New Mexican article posted in his farmers market booth alongside his favorite recipes. When he returned to farming under the tutelage of his uncle, a traditional farmer in Alcalde, Matt focused on hard-to-find gourmet and specialty vegetables such as sweet Italian peppers, hot yellow Bolivian purira chiles, Japanese eggplants, and bok choy. In a relatively few years, his niche marketing strategy has made him the top-selling vendor at the Santa Fe Farmers Market and enabled him and Emily to buy their own farm in Dixon. He now serves as president of the Santa Fe Farmers Market Institute and conducts Shop with the Chef programs at the market.

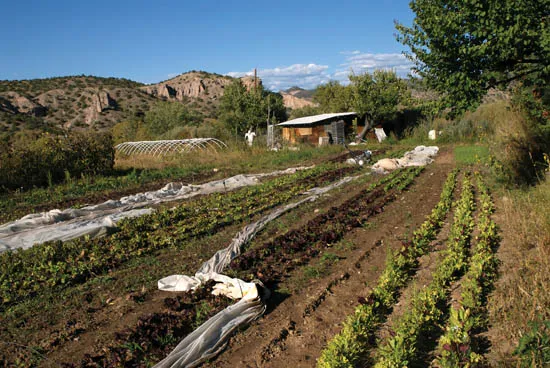

Brothers Teague and Kosma Channing , lifelong Santa Fe residents, with their lanky, bearded appearance, suspendered baggy trousers, and floppy broad-brimmed hats, might have stepped right out of nineteenth-century rural America. They took an interest in agriculture after visiting their mother’s relatives in the farm country of rural Poland, and then spent time in Mexico becoming fluent in Spanish, an essential survival skill in the villages of northern New Mexico. In 1993, at the respective ages of twenty-four and twenty, the Channing brothers started Gemini Farms in Truchas with three acres of fallow land and a small herd of goats; they built a house and barn from salvaged materials and locally cut roof timbers. The human population of their farm has been rather fluid, with a changing cast of friends and interns from Teague’s alma mater, Tufts University, and the University of California–Santa Cruz. The third permanent member of the group, Ann Lefevre, an experienced northern New Mexico farmer, fell in love with Teague and moved to Gemini Farms to care for the goats, milk them, and make cheese. Today they maintain a double-sized booth at the Santa Fe Farmers Market, where they sell a wide range of vegetables, including garlic, spring greens, potatoes, tomatoes, carrots, chile, basil, corn, squash, beets, beans, and parsnips. While they make a small profit at the market, much of their produce goes to feeding themselves and their friends, making Gemini primarily a subsistence farm. Despite the great amount of work it took to put the farm in shape, the land is leased, and the brothers do not expect to ever own it. Their experience with the realities of farming has left them as idealistic as ever. Their ambition is to someday move to a larger place of their own where they can grow wheat, pasture horses, and irrigate more sustainably with gravity-fed acequias instead of pumps, moving away from any kind of reliance on fossil fuels. Then they hope to form a community-supported agriculture group that will furnish food for the whole village.

The Channing brothers are by no means the youngest growers at the area’s farmers markets. That honor goes to the students of Camino de Paz Montessori Middle School and Farm near Santa Cruz, New Mexico. Parents who have looked into alternative education for their children are usually familiar with Montessori schools, where children are taught in three-year age groups in a child-size environment with small-scale furniture, and are encouraged to make decisions for themselves and to achieve competence over their environment. Many know that Maria Montessori (a contemporary of Rudolf Steiner, who founded the Waldorf schools around the world) was Italy’s first female physician as well as one of World War I–era Europe’s leading scientists, philosophers, humanitarians, peace advocates, and feminists. But few realize that she, like Steiner, also originated the concept of Erkinder , “earth schools” where children live close to nature, eat fresh farm produce, and perform chores related to growing and marketing food while doing classroom studies according to their interests, without pressure from teachers. Camino de Paz (“Road of Peace”), one of the few active Montessori Erkinders in the United States, is a working organic farm where young teens merge their practical experiences with outdoor education, arts, and music, as well as academic studies. Half of the students, who come from around the United States and from other places as diverse as Europe, South America, and New Zealand, are boarders at Camino de Paz or neighboring farms, while the other half are locals who live with their families in the predominantly Hispanic villages nearby. Using a team of Belgian draft horses instead of motorized equipment, the Montessori students grow about thirty different vegetables. They also raise sheep, goats, and free-range chickens, turkeys, and ducks. In the school’s commercial kitchen, students ages fourteen and up make processed products such as goat cheese, apple butter, herb pestos, fruit chutneys, hot salsas, chile caponata, and eggplant tapenade. Students sell these products, as well as the farm’s surplus vegetables, at the Santa Fe Farmers Market and through the farm’s community-supported agriculture group made up of about thirty families in the area.

While many of these farmers raise as wide an assortment of crops as possible, others become fascinated by particular vegetables. For instance, while Daniel Carmona of Cerro Vista Farm north of Taos grows a variety of produce—carrots, onions, beets, leeks, peas, kale, and lettuce—for his farmers market booth and CSA, his real passion is onions. Carmona says,

It’s really cold in Cerros, so the crops that do best here are crops that can take some frost. We’re not challenging the elements when we grow them. We do particularly well with onions, so I’m considering onions as a stand-alone crop. This year I’ve got an eighth of an acre of experimental varieties. They do extremely well here, and I might be able to make some money with them in the winter, when I’m not doing the CSA or the farmer’s market, because they store. After this year I’ll know what kind of onions grow and if I can make any money selling them in the winter. The farming season here is only about four months long, so we need to learn how to extend it.

Stanley Crawford is author of two books about his and his wife Rosemary’s lives at El Bosque Garlic Farm in Dixon— Mayordomo: Chronicle of an Acequia in Northern New Mexico (1988) and A Garlic Testament: Seasons on a Small New Mexico Farm (1992). Inter-viewed at the Santa Fe Farmers Market, where he stood behind a table heaped high with garlic fresh from the earth, Crawford filled me in on what he has been doing in the years since he wrote those books.

I’ve been growing garlic from the mid-’70s on, although it took us a few years to figure it out. We had about a five- or seven-year break in the farmers market—we stopped selling in 1997 or ’98 because I was working full-time for the Farmers Market Institute—but I kept coming to the market on Saturdays to help educate people about the permanent site. I stopped doing that in 2000, and then we didn’t farm for about four years. We went back to it last year on a small scale, and this year it’s a little bit bigger. The land was in pretty good shape because we only had gardens and the rest was in cover crops.

Crawford says of garlic:

I like the plant. I like planting it, cultivating it, harvesting it, processing it, all of that, but I’m not a gourmet garlic person. Rosemary feeds it to me raw when I have a cold or something like that.

You can plant garlic any time from September on, but in September you’re also in the same cycle as the annual and perennial grasses, so you’re going to get a lot of grasses coming up. If you wait until October or even November, before the ground freezes, you’re a little better off. The garlic will often not emerge at all until the spring, but it roots within a week of putting it in the ground even though it’s quite cold. We don’t mulch, we’ll probably start next year because we’ve begun to use drip irrigation. You can’t mulch with flood irrigation because the mulch blocks the rows. So we’re going to try that next year.

We also have basil and other things. Cutting basil is always nice because it smells so beautiful, it’s an incentive to keep going. When you get away from it for some years, it’s interesting how ...