Introduction

“Everybody Sucks 2016”

The 2016 presidential election—the most bizarre in my lifetime—may well be decided not by which candidate is liked more than the other, but rather by which is disliked less. Polls show that a majority of Americans have unfavorable opinions of both Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton and would strongly consider supporting a third-party candidate. Indeed, an Associated Press poll taken just before the nominating conventions found that “81 percent of Americans say they would feel afraid following the election of one of the two politicians,” and 25 percent said, “It doesn’t matter who wins. They’re scared of both.”1 This antagonism is apparently so widespread that an online store is selling bumper stickers, shirts, signs, and other paraphernalia with the logo EVERYBODY SUCKS 2016.

One comment writer to the New York Times explained that he wouldn’t vote for Trump or Clinton because, he said: “I’m resigned to having a terrible president starting next January, but there is no way I’ll be responsible for electing him or her.”2 Still more voters who plan to cast a ballot will be voting against, not for one of the candidates: “Three-quarters of voters say their selection would be motivated more by a desire to keep either Trump or Clinton out of the Oval Office” than by a desire to see their own candidate elected.3

Rarely have both candidates, both parties, and both houses of Congress been viewed so unfavorably4 by the voting public. Voters are angry, frustrated, and resentful, and with good reason: over the past several years, Congress has been incapable of passing even the most uncontroversial legislation, much less taking meaningful steps to address some of the serious economic and social problems facing our nation. This has resulted in the president taking constitutionally questionable steps, such as executive orders on immigration and on environmental regulations, which the courts have struck down. The result has been gridlock and stalemate.

There is frustration among working-class people whose take-home pay has not kept pace with those at the top of the economic pyramid, especially on Wall Street. There is anger among people of color regarding the symptoms of what they believe is structural racism manifested in high unemployment, high rates of imprisonment, and increasingly visible police bias. There is disappointment over our inability to deal rationally with what many view as a crisis regarding our immigration policy. And there is emotional fury—some rational, some not—about the state of our country and the world. Throughout history, radical left-wing extremists, as well as reactionary right-wing extremists, have exploited popular grievances such as these to their political advantage. This dangerous phenomenon is threatening many countries around the world today. It is also impacting the current election here at home.

The Shrinking Center

In the kind of political environment we are now experiencing, campaigns tend to emphasize the negative over the positive, the unfavorable over the favorable, and the downsides over the upsides. Voters look to simple-minded panaceas, to change for change’s sake, to revolution over evolution, to disruptive violence—and to extremes on both sides of the political spectrum. Hence the success of Donald Trump and the unexpected strength of Bernie Sanders—both of whom ran against more centrist, establishment candidates. The actress and Sanders surrogate Susan Sarandon explained why, in her view, “outsiders like Sanders and Trump have become so popular”:

“A lot of people felt disenfranchised. A lot of people are working so hard and getting nowhere. A lot of people are sick with politics the way it is… Bernie and Trump spoke to those people ….” Then she added, “It’s like the dark and the light … so will some of those people go over to the dark side … I don’t know, people are angry.”5

Although Hillary Clinton, herself a more centrist candidate, eventually won the Democratic nomination, she did so by moving away from the center and adopting some of Sanders’s left-wing positions and populist political rhetoric. Even after securing the nomination, she continued to drift leftward in an effort to secure the support of Sanderistas, who threatened to stay home or vote for Jill Stein of the hard-left Green Party. This is how Sarandon put it: “I’m waiting to be seduced. I’m waiting to be convinced.6… I’m waiting to hear something that speaks to me.… I’m not buying [Clinton] until she offers me something.”7

Some Sanders supporters have even threatened to vote for Trump over Clinton, whom they regard as too centrist. As the journalist Christopher Ketcham—another prominent Sanders surrogate—put it: “I’d rather see the empire burn to the ground under Trump, opening up at least the possibility of radical change, than cruise on autopilot under Clinton.”8

Clinton’s acceptance speech incorporated some of Sanders’s rhetoric and policies. But there is the fear that if Clinton tries too hard to seduce Sarandon and her fellow “Bernie or bust” radicals—if she moves too far away from the center—she could lose the support of traditional elements of the Democratic coalition who voted for candidates like Kerry and Obama but will not vote for Clinton if they perceive her to have moved away from them.

In the process of trying to secure the votes of such die-hard Sanders supporters, Clinton may well lose the votes of some centrist Republicans who were reluctant to vote for Trump and were considering voting for Clinton but may now end up voting for Trump. As one Republican friend put it to me: “If the choice is between a kooky Republican and a reasonable Democrat, I will probably hold my nose and vote Democrat. But if the choice is between a kooky Republican and a kooky Democrat, hey, I might as well stick to my own Republican kook.”

The current move away from the center and toward extremes—from centrist liberalism and moderate conservatism toward an ill-defined radical populism—is occurring in varying degrees around the globe, and it is a dangerous trend that threatens the stability of America and the world. The Brexit vote in Great Britain, the increasing power of both the hard right and hard left in many European countries, the growing influence of Islamic extremism within Muslim communities, the call for violence among some American radicals—both left and right—all point in a similar direction.

This trend has been replicated on university campuses around the world—campuses that train future leaders and voters. Indeed, students of both the hard left and the fundamentalist right seem less committed to classic academic values such as freedom of speech and the right of teachers to discuss difficult issues, and are increasingly obsessed with political correctness and suppression of dissenting or offensive voices.

The Global Movement Toward Extremes

Among the greatest dangers confronting the world today is the movement away from the centrist politics that have characterized most democracies over the past several decades and toward the extremes of both left and right. History has demonstrated that the growing influence of extremism on either side of the political spectrum stimulates the growth of extremism on the other side. The move toward hard-left radicalism provokes movement toward hard-right radicalism, and vice versa. The hard right is becoming more empowered in Poland, Slovakia, and Greece, and authoritarian leaders control Russia, Turkey, Belarus, and Hungary. The hard left has increased its influence in universities and labor unions and within some traditionally centrist liberal political parties, such as Labour in Great Britain and the Democrats in the United States. Populism is pushing toward extremes on both ends of the political spectrum. And extremism at one end tends to provoke extremism on the other end, as we are now witnessing. The growth of both extremes weakens the liberal and conservative centers and moves the world away from stability, rationality, tolerance, and nuance—and toward demagoguery, simple-mindedness, xenophobia, and intolerance.

Following the British vote to leave the European Union—which occurred despite the opposition of both major political parties in the UK—former prime minister Tony Blair, himself a centrist liberal, warned that instability will only increase unless the center can

regain its political traction, rediscover its capacity to analyze the problems we all face and find solutions that rise above the populist anger…. If we do not succeed in beating back the far left and far right before they take the nations of Europe on this reckless experiment, it will end the way such rash action always does in history: at best, in disillusion; at worst, in rancorous division. The center must hold.

Similarly, the French philosopher Bernard-Henri Lévy saw the Brexit vote as a “victory of the hard right over the moderate right, and the radical over the liberal left.”

Time and time again, history has demonstrated that extremism in politics—whether right, left, or both—is dangerous to the world. Extremists brook no dissent because they “know” the “truth.” We often forget that the benign-sounding term “political correctness” originated under Stalin, who murdered political dissenters, artists, musicians, and others who deviated from the politically correct line. Extremists begin by banning and burning books, and they end by banning and burning people.

The enemy of the hard left is not the hard right, because extremes develop symbiotic relationships with each other. The real enemies of the radical left are centrist liberals, just as the real enemies of the reactionary right are centrist conservatives.

It is these centrists, both liberal and conservative, who are being squeezed by the extremes. It is centrism itself—with its stability, its willingness to compromise, its tolerance for divergent views, and its capacity to govern effectively if not perfectly—that is currently in the crosshairs of populist extremism.

We are seeing that disturbing phenomenon all over the world. It must not be allowed to take root here.

The Importance of the 2016 Election

In terms of stability of the world and of our nation, the 2016 presidential election may be among the most important in generations. Many voters cannot vote for a destabilizing and unpredictable candidate like Donald Trump, or for a Republican Party that opposes the reproductive rights of women, the right of gays to marry, the right of citizens to health care, and other extreme Republican policies, such as opposition to effective gun control. But many voters also distrust Hillary Clinton and are wary of the foreign policy of the Democratic Party, especially with regard to terrorism and the Middle East. They are particularly concerned about the efforts of the left wing of the Democratic Party to weaken our nation’s support for Israel. Centrist Democrats are also wary of hard-left “identity politics” that emphasize group rights over individual rights. Moderate Republicans are equally wary of Trump’s emphasis on group wrongs that tends to lump together “the Mexicans,” “the blacks,” “the gays,” and other groups of individuals based on their ethnicity, gender, or sexual orientation.

The result of this movement toward extremes has been a weakening of the center and confusion among many centrist voters, who don’t like the choices currently on the ballot. They reject what they see as the growing influence of the hard left within the Democratic Party—especially but not exclusively with regard to foreign policy and identity politics—and they cannot accept the religiously motivated domestic policies of the Republican hard right. Many centrists—both Democrats and Republicans alike—do not feel they now have a comfortable home in either party, and they are not aroused by either candidate.

Over the past months, I have been making these observations in my speeches and public appearances. Invariably, dozens of people come up and say, “That’s me! I, too, am a domestic liberal who supports Israel and a more muscular foreign policy. I’m worried about what is happening on university campuses, with left-wing suppression of speech. I’m not sure I can vote for Democrats who demonize Israel and pander to hard-left identity politics, but I don’t think that I can vote for Republicans who are anti–gay rights, women’s rights, and other liberal programs. What should I do?”

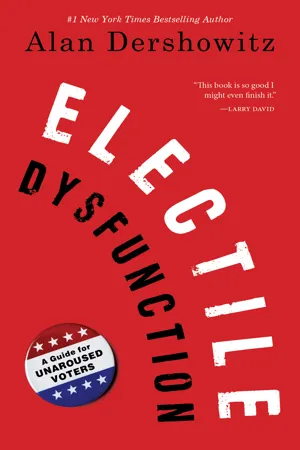

Hence this book. It describes the political dysfunction and the dilemma faced by centrist voters who are not aroused by either candidate or party, and it proposes constructive ways to deal with it.

In the chapters to come, I will analyze how politically perplexed citizens, who are torn between liberal domestic values that incline them to support Democratic candidates, and foreign policy values that might incline them to support Republican candidates, might think about this conflict. As a teacher for half a century, I never told my students what values to accept or which candidates to support. I always helped guide them to conclusions based on their own sets of values. I will try to do the same in this book. I will not tell readers whether to support Democratic or Republican candidates. Instead I will try to sort out both the domestic and foreign policy values that each reader might possess. I will then set out a process for assessing these values and prioritizing them.

My goal is to have each reader think for her or himself about the comparative strength of each of their values and how they might prioritize them in an effort to come to rational conclusions regarding candidates and political parties. I will not try to hide my personal views as to which of the current presidential candidates I believe will do a better job of moving us toward centrist liberalism. ...