![]()

Chapter One

THEMES IN SCOTTISH HISTORY

It is certainly a legitimate function of history to produce, as the cliché goes, a usable past. But there is a danger in our obsession with mapping out the routes to the present, because in doing so, we slice off all that is not ‘relevant’ and thus distort the past. We eliminate its strangeness. We eliminate, most of all, its possibilities. History should do more than validate the inevitability of the present.

– Richard White, ‘Other Wests’1

During their heyday in the ninth and tenth centuries, the Norse enjoyed military and political supremacy along the coastal areas of much of western Europe; they unsettled the existing political order, imposed their own leaders and developed their own settlements. Yet, in most locales, within a few generations they were beginning to lose their dominance and Gaelic culture proved resilient enough to assimilate the would-be conquerers. By the late medieval period, the Gaels of the west of Scotland, most of whom had a mixture of Norse and Gaelic ancestors, were recounting legends of how Gaelic warriors such as Somerled had liberated their lands from Viking usurpers. The alienation of Highlanders from their own Scandinavian ancestry once they had become Gaelicised is one of the many ironies of history that alert us to the dangers of assuming that ethnic identity reflects ‘racial’ origin.

Gaeldom’s comeback is celebrated in tales such as the following legend from Argyll. Like many local legends, it explains the origin of a significant place name, which adds a sense of historical weight and veracity to the tale. The place name Gleann Domhainn (‘Deep Glen’) may symbolise how Gaeldom withdrew after the Viking attacks to inland sanctuary until it regained strength. Despite several generations of dominance in the west, the narrative implies that the only legacy left by the Norse is a series of place names signifying their defeat.2

The Norse once made a sudden descent from their ships on the lower end of Craignish. The inhabitants, taken by surprise, fled in terror to the upper end of the district and didn’t stop until they reached Slugan (‘the Gorge’) in Gleann Domhainn.

Once there, they rallied under a brave young man who took their leadership and slew the leader of the invading Norse with a spear. This inspired the Craignish men with such courage that they soon drove back the disheartened Norse across Barr Breac river. As they retreated they carried off the body of their fallen leader Olav (Amhladh in Gaelic) and buried it on a place on Barr Breac farm which is still called Dùnan Amhlaidh (‘Olav’s Mound’). The Craignish men also raised a cairn at Slugan to mark the spot where Olav was slain.

The old adage ‘History is written by the winners’ acknowledges that people experience events differently, according to their own perspectives and circumstances, and that the writing of history has frequently favoured one party to the detriment of others. The labels used for political movements, factions and players often betray biases: whether a person has been represented as a rebel or a hero has been determined not so much by the deeds he has done as whether or not his story was written by someone sympathetic to his cause.

The writing of history is inevitably a matter of interpretation: not all of the innumerable people and actions over a space of time can be accounted for, so the scholar must decide which factors are most responsible for the outcomes of social processes and how people are affected by the results. He must decide whose story to tell and how to tell it.

The story told about the Highlands has long been dominated by the assumption that the region has always been an isolated and remote backwater, and by a negative appraisal of the Gaels themselves as a people. Both of these biases have served to marginalise the Gaels in the writing of Scottish history. Documents portraying Highlanders as primitives naturally inclined to resist the rule of law and principles of progress have often been taken at face value. The perspectives of the Highlanders themselves have been too easily ignored, especially when pitted against those of others assumed to be more ‘civilised’. The author of the Sleat history of the MacDonalds complained in the mid seventeenth century about the anti-Gaelic prejudices which distorted the way in which Scottish history was written in the Lowlands:

These partial pickers of Scotish chronology and history never spoke a favourable word of the Highlanders, much less of the Islanders and Macdonalds, whose great power and fortune the rest of the nobility envied [. . .] he relates that such and such kings went to suppress rebellion here and there, but makes no mention of the causes and pretences for these rebellions. [. . .] Although the Macdonalds might be as guilty as any others, yet they never could expect common justice to be done them by a Lowland writer.3

When Gaelic folklorist J. G. Mackay addressed the Glasgow Highland Association in 1882, he observed that ‘to many Highlanders the extraordinary antipathy and determined antagonism with which they have been treated by pragmatical historians has long been a most unaccountable mystery’. While historians made an effort to understand the motives, circumstances and affiliations of English and Lowland subjects, ‘the Highlander could have no such sentiments, he could only be activated by his love of plunder and bloodshed’.4 Even near the end of the twentieth century, the accomplished scholar John Lorne Campbell, who spent his life recording and publishing Gaelic materials of all kinds, remarked that Highlanders were still grossly misrepresented in historical scholarship:

Unless a historian possesses some knowledge of the Gaelic language and its written and oral literature, and has the insights that that knowledge bestows, it is very difficult not to be borne down by the accumulating weight of official assertions and propaganda, and arrive at the mental state of accepting them without question. [. . .] Far too long have the Scottish Gaels been treated by historians as non-persons with no legitimate point of view.5

We can better understand a society when we have examined the forces, events, and agents that have influenced its experiences and development. This chapter attempts to provide a summary of the history of Scottish Gaeldom: the people and events which provide the subjects and topics of Highland literature; the circumstances and trends which have influenced the forms and functions of its culture; the conditions and constraints which have affected the allegiances and political decisions of Highland leaders; the factors that have influenced the living conditions, social institutions and roles of the generality of Highlanders. This outline is intended to provide a context for specific aspects of Gaelic culture explored in depth in following chapters.

CELTIC BEGINNINGS

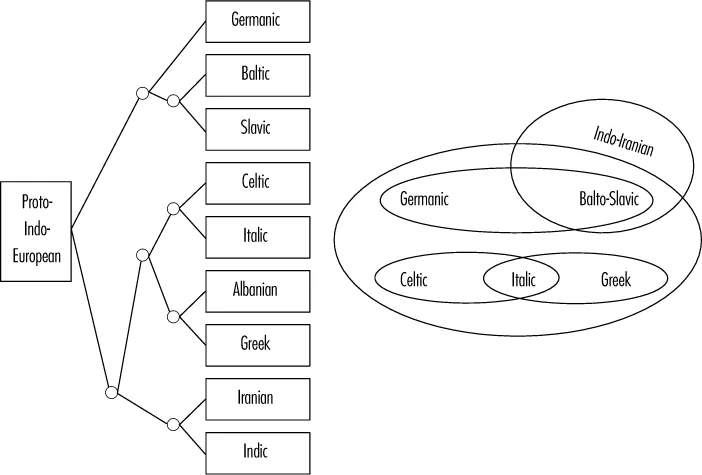

The term ‘Celtic’ has become popularly associated with particular people, places, art styles, musical styles, and so on. There are many difficulties with using the term ‘Celtic’ in these imprecise ways, however; scholars use it to refer to a family of languages belonging to the greater Indo-European family. Celtic languages are ultimately related, albeit at several removes, to other languages familiar to us in Europe and Asia, such as French, Italian, Hindi, and Persian.

In theory, the many Celtic languages (and their associated cultures) are derived in some way from a Celtic parent. The relationships between ‘parent’ and ‘child’ cultures, however, are complex and prevent us from making simplistic assumptions about a unified Celtic culture existing anywhere at any time. Earlier generations of scholars, living during an imperial epoch, assumed that the spread of Celtic languages and cultures could only be explained by an invasion of Celtic-speaking people who conquered new lands because of superior technology. The newer paradigm of Celticity instead proposes a long period of cultural development beginning in the late Bronze Age, from 1200 to 700 BC, driven by the influence of trade and networks of a Celticspeaking élite.6 The diffusion of Celtic languages and cultures happened in such a loose way (rather than being imposed by a centralised state from a prescribed standard) that we cannot speak of a single Celtic people, way of life, or identity, but rather a family of inter-related languages and cultures. ‘Celtic’, then, is an abstraction of convenience for a set of features which are found in concrete form in specific times and places, even though not all ‘Celtic’ tribes shared all of the same characteristics.

Figure 1.1: Two models of Indo-European language families

Although we get different kinds of evidence from archaeology, place names, inscriptions, and historical sources, it is safe to say that for several centuries before the birth of Christ Celtic-speaking peoples were living across a large section of Europe.

Originally they extended in a broad swath from south-western Iberia, through Gaul and the Alpine region, into the Middle Danube, and one group of settlers, the Galatians, introduced Celtic into central Asia Minor.7

Britain and Ireland were occupied by Celtic-speaking peoples at the dawn of recorded history and had been for some time. This conclusion is confirmed primarily by personal names, tribal names, and place names recorded in early documents and by the testimony of early Classical authors. Archaeological evidence also allows us to interpret some features of surviving material culture – houses, forts, burials, clothing, artistic styles, etc. – in relation to other cultures classified under the rubric ‘Celtic’.

Pytheas, a Greek writing as early as 325 BC, referred to the ‘Pretanic Isles’; the Romans referred to the island as ‘Britannia’. These territorial names are based on the Celtic tribal name Britanni. An earlier and purely territorial name for the island, *Albiu, survives to the present day in Gaelic in the form Alba. In the second century AD the Greek geographer Ptolemy preserved a list of the names of Celtic tribes in various parts of Britain and Ireland. Some tribal names recur in several parts of the Celtic world: there are ‘Brigantes’ in eastern Ireland and northern England; ‘Parisi’ in eastern Yorkshire and ‘Parisii’ in France. Similarly, there was a ‘Cornavii’ in Caithness and a ‘Cornovii’ in the English mid-lands, a ‘Damnonii’ in the Clyde valley and a ‘Dumnonii’ in Cornwall.8 It is not clear if these were branches of the same tribe that migrated to different areas, or simply names based on similar origin legends or mythological founders.

The Insular Celtic languages (those spoken in Britain and Ireland) are generally classified as P-Celtic (or Brythonic) and Q-Celtic (or Goidelic) because of how the ‘Q’ consonant inherited from the theoretical linguistic ancestor, Proto-Celtic, evolved in two descending branches: it was simplified as a hard ‘c’ consonant in Goidelic languages, while in Brythonic languages it became a ‘p’ consonant. There were speakers of both branches of Celtic on both islands (as the tribal names above suggest) during the late Iron Age, but on the whole most of Ireland was Goidelic and most of Britain was Brythonic.

Roman troops under Claudius invaded the south of Britain in AD 43 and after consolidating their victories, Gnaeus Julius Agricola, Roman governor of Britain, moved armies north to invade Scotland in AD 79. His ability to march as far as the Tay suggests that he had already formed relationships with the tribes of southern Scotland before the campaign. The Romans were expert at military strategies such as proxy warfare and servitor imperialism: it was common for them to form pacts and client relationships with native tribes (and displaced élite) along the frontier at each stage of territorial expansion to make subjugation easier.

Lasting military conquest and occupation in Scotland, however, proved elusive for the Romans: several strings of forts were built to control territory and assert authority, but by AD 165 the army had withdrawn to Hadrian’s Wall. Such was the ability of the northern tribes to harass the Roman forces that they bribed the Maeatae (a tribe that occupied the area around modern Stirlingshire) in exchange for a cessation of hostility and the release of prisoners. The Romans were under attack by a broad ‘barbarian conspiracy’ in the fourth century which they were never able to contain. Problems within the empire itself precipitated the collapse of its occupation of Britain in the early fifth century; by AD 410 the forces at Hadrian’s Wall were dispersed.9

Despite the inability of the Roman Empire to control and assimilate the Celtic tribes of Scotland, particularly north of the Antonine Wall, the Roman presence had significant consequences. South of the Forth–Clyde line tribes such as the Votadini (later known as the ‘Gododdin’) who aligned themselves with the Romans were able to flourish while others collapsed. Direct Roman influence was considerable in the ‘buffer zone’, not least because it brought Christianity to the Brythonic peoples perhaps as early as AD 200. C...