![]()

PART ONE.

SOCRATIC LOGOS

![]()

CHAPTER I

PROVOCATIONS OF SOCRATIC LOGOS: APOLOGY OF SOCRATES

“The lord whose oracle is in Delphi neither speaks out nor conceals but gives a sign.”1 This saying of Heraclitus itself gives a sign. This saying is a sign which, if we attend properly to it, makes manifest what is initially at issue in the problem of Socratic logos. It poses “legein”—hence “logos”—over against “concealing,” and it puts both in opposition to “giving a sign.” The latter is named as the activity proper to Apollo, who signifies through the oracle at Delphi and who is “lord” over man—that is, who exercises command over man in that signifying through the oracle. Apollo, speaking through the oracle, gives a sign of such a kind that what is signified is neither totally illuminated (“spoken out”) nor totally obscured (“concealed”); nor is it just partly illuminated and partly left obscure. Rather, the sign is given to be interpreted, and its signifying commences only with the commencement of the interpretation. Philosophy as presented in the activity of Socrates originates through such interpretation. And even beyond its point of origin philosophy remains engaged in a perpetual interpreting of those most familiar Delphic signs “Know thyself and “Nothing in excess.” For taking up the question “What is philosophy?” in the form of the question “Who is Socrates?”—for taking up, specifically, the question of Socratic logos—it is appropriate to begin with that Socratic logos which most explicitly brings to light the bond joining Socratic logos as such to that divine saying, that sign-giving, in which man’s subordination to Apollo is put at issue.

The

Apology of Socrates (

) is the only

Platonic dialogue which includes the name of Socrates in its title. This corresponds to the fact that the

Apology is the dialogue which most explicitly has to do with the question “Who is Socrates?” Furthermore, the

Apology is unique in its

way of dealing with this question. For, in the first place, it deals with this question within a context in which it is the most pressing of all questions, in which the answer to this question is literally a matter of life or death—hence the exclusiveness with which the

Apology is dedicated to this question. And, secondly, by virtue of this context, the answer which Socrates presents is addressed explicitly to “the many,” to the men of Athens, to men in the city—which is to say that in the

Apology Socrates carries out that way of answering the question “Who is Socrates?” which demands the least on the part of those to whom it is addressed. The

Apology is peculiarly appropriate to the beginner.

In all three of its dimensions the Apology poses an answer to the question “Who is Socrates?” First of all, Socrates simply says-in several regards—who he is. He says this especially in the testing of the various counter-images that are presented in the form of the accusations against him. What is especially remarkable in this connection is that this way of affirming who he is constitutes, not only a refutation of the counter-images and an assertion over against them of a truthful image, but also a concrete exhibition of that very practice which defines who Socrates is. The very way in vyhich Socrates constructs his image—in the course of confronting, testing, and refuting the opinions embodied in the accusations—exemplifies the image constructed. Consequently, the question “Who is Socrates?” is answered in the Apology not only by what Socrates says but also by his way of saying it, by what he does; Socrates’ speech is a testimony not only in speech but also in deed (cf. 32 a)-not only in logos but also in ergon.2

Neither the description of his practice as one of questioning men in the city nor the exemplification of such questioning in deed permits, however, an adequate unfolding of the depth that belongs to Socrates’ practice. This depth is primarily unfolded, rather, in the mythic dimension of the Apology. Socrates explicitly presents his practice as originating in a response to a sign given through the Delphic oracle. At the simplest level, this means that the already established mythical tradition supplies a context for Socrates’ presentation of his peculiar practice and its motivation. But it also means something more fundamental. Socrates, as one who is engaged in unlimited questioning, is compelled to carry this questioning so far that finally he must question the questioning itself, must ask “What about the what?” “Why the why?” And even if he should resist this radicalization of his questioning, it is forced upon him when the men of Athens bring him to trial precisely because of what his incessant questioning has provoked. What is crucial is that Socrates “answers” the second-order question, the question about questioning, by setting his practice back upon a mythos. He confronts this most dangerous question—the question which amounts to a calling of questioning, of his practice, into question—by explicitly attaching his practice to a mythos, that is, to a basis that is not immediately dissolved by the reiterated recoil of questioning upon itself.

Section 1. The Prologue to the Apology (17 a — 19 a)

The

Apology is composed primarily of three speeches: first, the long defence speech (19 a — 35 d), second, the speech in which

Socrates discusses and proposes alternative penalties (35 e — 38 b), and, finally, the speech delivered by Socrates after the sentence has been imposed (38 c — 42 a). The first speech is preceded by a prologue which consists of two parts: a preface (

) in which Socrates speaks about speech and a setting forth (

) of the charges. We must attend to the opening with special care.

(a) The Preface (17 a — 18 a)

Socrates begins:

How you, men of Athens, have been affected by my accusers I do not know; but, however that may be, I almost forgot who I was, so persuasively did they speak; and yet there is hardly a word of truth in what they have said (17 a).

In this opening statement and the elaboration of it that comprises the rest of the preface there are three principal issues to be noted.

First, Socrates refers to the persuasiveness of his accusers’ speeches and mentions that he has been so affected by them that he almost forgot who he was. Thus, the Apology begins with the identity of Socrates (who he is) being thrown into question. This is what his being brought to trial amounts to—a placing of the question “Who is Socrates?” in the arena of contention. Indeed, Socrates suggests that his accusers contend so persuasively that he almost forgets the answer which he presumably brought with him to the trial. But he does not quite forget; and, in fact, his answer to his accusers—that is, the body of the Apology—is Socrates’ manifold assertion of who he is. As such it is the measure of the irony involved in Socrates’ opening his defence with the suggestion that he has barely escaped being plunged into self-forgetfulness by the persuasive speeches of his accusers.3

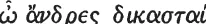

Second, it should be observed that Socrates addresses the members of the court as “men of Athens” (

) rather than using the more customary expression “judges” (

). In contrast to Meletus, who does not hesitate to call them “judges” (24 e), Socrates studiously avoids so addressing them throughout his entire defence speech. Only in the last part of his final speech, in which he addresses himself only to those members of the court who voted for his acquittal and in which he draws the contrast between those who claim to be judges and those true judges who sit in judgment in Hades (41 a)—only there does he finally use the other form of address (

). Only those who have voted for his acquittal are addressed as judges, and they are so addressed only after they have proved themselves by their vote.

4 Socrates says that in calling them judges he is speaking correctly (40 a). The point is that inasmuch as Socrates takes it upon himself to decide to which of the “men of Athens” the name “judge” belongs, he is himself assuming the stance of a judge.

5 In the

Apology we are presented not only with the judgment passed by the would-be judges on Socrates but also with Socrates’ passing of judgment on those who claim to judge him. Socrates judges the would-be judges. This is presumably why he remarks at the very beginning that he does not know how they have been affected by the speeches of his accusers: he does not know whether they are sufficiently in possession of the proper virtue of a judge (cf. 18 a) to have withstood the persuasion of his accusers, and he will come to know this only by himself passing judgment on them in the course of the trial.

Socrates brings the would-be judges to trial, and in trying these “men of Athens” he places Athens itself on trial.

Socrates insists, finally, that there is hardly any truth in what has been said by his accusers. Specifically, he adduces as the most evident of those lies that they have clothed in persuasive speech their contention that he is a clever speaker. It is significant that Socrates seizes upon this particular issue. For it is, as he notes, a contention which his subsequent speaking will refute, not only in speech but also in deed; his defence speech will not be a clever speech in the sense suggested by Socrates’ accusers.

6 Yet, still more important, Socrates’ focusing upon this issue, which he then elaborates in the remainder of the preface, has the effect of making his prefatory speech of defence, which anticipates the defence as a whole, into a description of his relation to speech. From the very outset Socrates’ relation to

logos is posed at the center of the considerations, and Socrates’ defence is prefaced by a speech about speech, about the speech of Socrates in contrast to that of his accusers. Socrates informs the “men of Athens” that from him they will not hear fine speech embellished with choice phrases, that, instead, he will speak in the same way that he is accustomed to speaking in the market place and elsewhere; in other words, he indicates that in his defence speech he will continue precisely that kind of speech which defines his practice, which is to say that his defence speech will itself constitute an exemplification of that very practice against which the accusations have been brought. To the extent that such practice, such Socratic

logos, transcends the city, to the extent that it is intrinsically at odds with the city, Socrates is, as he says (17 d), a foreigner—not, however, just because he is in court for the first time and not because he is ignorant of the speeches of the courts. The gulf which separates Socratic

logos from the speech of the courts and makes it seem almost like a foreign tongue is anything but a mere lack of familiarity. On the contrary, what, most comprehensively, constitutes this gulf is the dedication of Socratic

logos to truth (

): “Now they, as I say, have said little or nothing true; but you shall hear from me the whole truth” (17 b). But what does this mean—that Socrates will speak the truth in contrast to those who deliver the finely embellished speeches of the courts? What does it mean to speak the truth, and what must be the character of Socratic

logos if its distinctiveness lies in its dedication to truth?

At this point what is important for our inquiry is not that we have an ample supply of answers to this question but rather that we let there be something genuinely questionable in this question, that we take the utmost pains to avoid letting the question be dissolved by the all-too-available semblance of obviousness. A first step in this direction is provided if we take note of a connection which Socrates later makes between presenting the truth and speaking in such a way as not to hide anything from those who are addressed (24 a). In speaking the truth Socrates speaks in such a way as to avoid letting what he speaks about be hidden. But what he speaks about primarily is himself, and in speaking the truth with regard to himself he is speaking in such a way as to make manifest who he is. What must be the nature of truth and of logos and what must be their connection if true logos is that which is dedicated to taking a stand against letting thing...