A School for Maritime Indians

The Targets Were Children

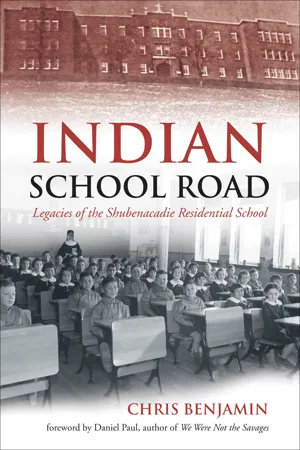

In its thirty-seven years, more than two thousand children were taken to the Shubenacadie Indian Residential School. Many were traumatized by the school’s environment of fear and self-loathing. As a school, Shubenacadie fails any modern academic standard, and any similar test of its day. The records that weren’t destroyed and the testimony of its survivors show that the institution was really a self-sustaining work camp, complete with livestock and produce, for much of its existence. The real reason for the institution wasn’t education. It had two main functions: house poor or parentless children and assimilate Indians into the dominant culture.

Although Indian Affairs had officially dropped the goal of getting Indians to give up life on the reserve and become part of Euro-Canadian society in 1899, comments from Department officials show that the Shubenacadie residential school was at least partially designed to assimilate the Mi’kmaq. Officials hoped to eliminate Aboriginal cultures and languages by creating a break between young people and their families and communities. This process has been called cultural genocide.

More than many other residential schools, Shubenacadie was closer to an orphanage—with all the worst connotations of that word—than a school. The targets were children from the poorest eastern First Nations families, mainly Mi’kmaw, Wolastoqkew, and Peskotomuhkatiyik—orphans and foster children who had limited means to resist. Children without access to on-reserve day schools were also targeted—even though many reserves lacked schools because Indian Affairs would not pay for them. The creation of the Shubenacadie residential school went hand in hand with Indian Affairs’s ongoing attempt to centralize the Mi’kmaq into as few locations as possible. It was seen as the cheapest and most effective way to deal with them. But the assimilation effort was too poorly funded to work. A lack of funding resulted in overcrowding: the school was built for 125 students, but its enrollment numbers were never so low until its final decade. Sickness and injury were rampant. For the students, who were not allowed to leave and were punished seemingly at random, it was a prison. The conditions were so bad that one resident, who later became a POW during the Second World War, told CBC that of the two experiences, one was no worse than the other.

The Only Region Without

a Residential School

It was a strange time to open an Indian residential school. The Mi’kmaq population continued to struggle, with only around two thousand left in the region. Recent studies had shown that most of the youth leaving residential schools in the rest of Canada returned to their reserves, having lost their mother tongues, and had no chance of finding employment in white Canada.

Political cartoonist Michael de Adder’s astute depiction of the Shubenacadie Indian Residential School as it was seen by the outside world versus the experience of its child residents.

The United States, whose residential school system had initially served as a model for the Canadian system, was now moving away from it, or at least reforming it to instill more respect for Indigenous American cultures. This change was based on three years of research by a team of legal, economic, health, educational, agricultural, and social work experts led by Lewis Meriam. In their 847-page report, entitled The Problem of Indian Administration and often referred to as “The Meriam Report” (published in 1928), the researchers wrote: “Provisions for the care of the Indian children in boarding schools are grossly inadequate.” Specifically, it detailed that the children were malnourished and their health poorly cared for. Teaching standards were low and culturally insensitive. The schools only stayed open on the backs of student labour. Meriam recommended an education system based on integrating children into mainstream public schools, a policy Canada would adopt within twenty years. The report moved some white Americans to push for reform and greater respect for First Nations cultures within the education system. The idea of removing children from their homes, parents, and communities was suddenly being called out in the mainstream. In practice though, the American residential school system would survive another forty years, and Canada’s for longer.

In Canada, the fifty-four-year-old system had long suffered criticism for its failure to educate or care for its wards. In short, it was doing a better job—at great financial expense—of infecting them with tuberculosis and other deadly illnesses than teaching them about the White Man or anything else. The Department of Indian Affairs was also well aware of allegations of physical and sexual abuse in many of the schools by this time. For the most part, these were either ignored or dealt with by moving the accused to another religious assignment or residential school. Despite losing their mother tongues, the children who attended the schools still had weak English skills. The focus on “vocational training,” via slave labour, to help supplement the costs of running a boarding school had not made the residents employable. It was clear that they’d have done better learning practical skills in their own communities.

Years before Shubenacadie opened, residential schools had come to be seen in most of Canada as places of disease and death, a failed experiment. Minor changes were made. Teachers received raises. Residents got one warm meal a day and got to play games sometimes. More than five thousand children lived in seventy-one residential schools across Canada, but First Nations children in the Maritimes had so far avoided that fate. And yet, there were rumblings here. Even back in 1885, John A. Macdonald had lamented that “Maritime Indians” didn’t make their children go to school and thought perhaps a residential school was the answer. Edgar Dewdney, the superintendent general—now called deputy minister—of Indian Affairs, said the same thing to the Governor General a few years later. By this point, the Maritimes was the only region in Canada without one. Two decades later, a low-level bureaucrat and man of faith came to the same conclusion.

Father F. C. Ryan was the New Brunswick supervisor of Indian schools in 1911 when he wrote to Ottawa urging Indian Affairs to establish a residential school in the Maritimes. Without it, he believed, the Mi’kmaq and Wolastoqiyik were unfit for “the battle of life.” He mostly worried for the boys. The girls at least learned sewing and knitting in day schools. The boys had nothing. They needed to learn useful skills, like carpentry, blacksmithing, tailoring, and farming. Father Ryan’s petition was ignored.

Eight years later, another New Brunswicker took up Father Ryan’s call. H. J. Bury was the supervisor of Indian timber lands for the region, whose job it was to help make money off what was left of reserve lands. He wrote regular memos and reports to his superiors in Ottawa between 1919 and 1934. In numerous letters to his superiors, Bury noted that hundreds of Mi’kmaq in Nova Scotia were squatting in shacks, especially in the Halifax area. The owners of the land had told them to beat it, but they found it impossible to make a living on reserve.

Nova Scotia Indian Superintendent A. J. Boyd had long been pushing the Department to buy land for off-reserve Mi’kmaq, but Bury didn’t trust the Mi’kmaq to stay put. He wanted them relocated to Indian Brook reserve, near Truro, for the time being. Like many at Indian Affairs, Bury believed in putting the Mi’kmaq onto just a few large reserves. He suggested selling off the reserves with poor land and buying new, more arable land around Truro, Shubenacadie, and Whycocomagh. In 1924 he estimated that there were about 2,400 Mi’kmaq in Nova Scotia, with 1,500 living on the province’s twenty-six reserves. Many were still nomadic, but about 540 Mi’kmaq were squatting near the city. Bury was convinced that if the Mi’kmaq were given better land and taught farming as well as other trades, they’d be much better off.

Like centuries of “Indian workers” before him, Bury saw farming as the only way to civilize the Mi’kmaq. The first missionaries had seen that the nomadic Mi’kmaw lifestyle made it impossible to keep pace and spread the word of Jesus. To the government, farming was the European, and later Canadian, way. And Indian farmers were as good as Canadian. Ironically, while federal government workers pushed farming on the Mi’kmaq, the Nova Scotia government profited on the image of the Indian woodsman. It toured elaborate displays in large American cities depicting Mi’kmaw hunting guides in buckskins. One guide demonstrated his moose-calling skills on NBC.

Bury, on the other hand, suggested a residential school on a farm as the means to contain roving Mi’kmaw children in one place, to learn farming in a caring environment. Agricultural education in public schools was being phased out, but Indian Affairs still supported the concept in residential schools. The proposed school was a small ingredient in Bury’s larger plan to amalgamate the reserves, a process that would save a bundle by employing three full-time Indian Agents—who would presumably be better qualified—instead of nineteen part-timers. He suggested both of these things in a report to Duncan Scott. Bury noted with some envy that there were more than seventy residential schools nationwide, and none in the neglected Maritimes. He suggested Truro as the ideal location.

Bury wasn’t alone in this opinion. Cameron Heatherington, the Indian Agent for Guysborough, had already written to Indian Affairs requesting a residential school for those who didn’t live near a day school. A. J. Boyd, superintendent of Indian Affairs for Nova Scotia, also supported a residential school. He felt that Canada’s education policy was failing the Maritime Indian. He’d been to Western Canada to study the residential school system and found the schools “highly successful.” He had apparently missed much of the recent news on Peter Bryce, who had exposed the schools as death traps, rife with disease.

Boyd submitted a May 1925 report urging Indian Affairs to build a residential school and farm in Nova Scotia. “The current [day school] system is unacceptable,” he wrote. “It keeps the Indian down and does not advance him in any way towards becoming a self sustaining and useful citizen.” A residential school would isolate the young Indian from bad influences on the reserve, he argued, and teach him the “proper way of life.” It was essential to educate the Indian out of the Indian.

Father Ryan, perhaps sensing the momentum shift, resumed his campaign of fourteen years earlier. He again wrote to the Department advocating for a residential school in the Maritimes, mainly to house and school “delinquent Indian children,” particularly orphans. He argued this time that the building of the school was a matter of justice, that without it all Maritime Indian children were being dragged down into a life of delinquency. Ryan felt that nothing good had come from having “prosecuted Indian after Indian.” The school was the progressive thing to do. He wrote that the current “educational system is only good for a few, and these few are soon overcome by the conduct of the delinquent…all due to the want of this one institution.” His letter was ignored.

The next year Father Ryan tried again, this time using an economic report arguing that while a new residential school might seem expensive, the government actually couldn’t afford not to have one. The government was paying Mi’kmaw families to look after Mi’kmaw orphans, “a grave financial drainage,” and because those payments were making the families lazy, the government could solve the Maritime “Indian Problem” by sending those kids to residential school instead. “The Indian question in the Maritime Provinces will then, and only then, be solved for all time,” he wrote.

It’s Official

A. J. Boyd wasn’t a popular figure among the Mi’kmaq. They had petitioned Duncan Scott in Ottawa several times to fire Boyd. Ben Christmas, chief of Membertou First Nation, accused Boyd of drawing two salaries while the Mi’kmaq lived in poverty. He also said Boyd rarely visited the reserves and was “not capable to protect an Indian,” having let the reserves become “deplorable and a disgrace.” Nevertheless, given his position as superintendent for the province, Boyd’s voice of support for a Maritimeresidential school was hugely influential. In fact, his esteem with the Mi’kmaq, and their opinion in general, was of no concern to Indian Affairs. Despite the fact that Ottawa was just beginning to acknowledge the failure of the residential school system to assimilate Aboriginal peoples, Indian Affairs Deputy Secretary J. A. MacLean took Boyd’s letter seriously enough to tour the Maritime reserves in the fall of 1926. When he returned to Ottawa, MacLean wrote Boyd to say he agreed wholeheartedly with the need for a residential school “convenient to the railway and sufficient in size to accommodate 80 children under the Catholic Church as virtually all Indians in the area belong to that faith.”

Duncan Campbell Scott, the sixty-four-year-old deputy superintendent of Indian Affairs, was also a supporter. In the previous few decades Scott had opened dozens of new schools, and he considered starting one on the East Coast a primary career goal. “When we have this school established one of the desires of my official life will have been accomplished,” he wrote to the Halifax Catholic Archdiocese in 1926. Doing so would make the residential school system coast-to-coast-to-coast, with schools in the west, north, and east. He also wanted the school within view of the highway and rails, “so that the passing people will see in it an indication that our country is not unmindful of the interest of these Indian children.”

Scott officially announced his intentions to build a “home and school” in Nova Scotia nine months later, in another letter to A. J. Boyd. “The children will receive academic training, as well as instruction in farming, gardening, care of stock, carpentry in the case of boys, and for the girls, domestic activity,” he wrote. There would be a barn and henhouse on site...