![]()

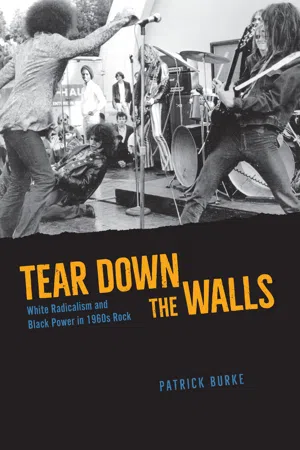

Lincoln Park, Chicago, August 25, 1968

On Sunday, August 25, 1968, on the eve of the Democratic National Convention in Chicago’s International Amphitheatre, the MC5, a rock quintet, performed for protesters in nearby Lincoln Park. Early announcements by the Yippies, the playful radicals who planned a “Festival of Life” to protest the convention, had promised performances by a wide array of musicians, including Country Joe and the Fish, the Fugs, and the Steve Miller Blues Band, with invitations outstanding to everyone from Bob Dylan to Jefferson Airplane to the Beatles.1 Yippie provocateur Abbie Hoffman proclaimed that “while they [the Democratic delegates] go through sterile roll calls, we will dance in the streets to Country Joe and the Fish.”2 The MC5, already notorious in their native Michigan for their hard-driving music and revolutionary politics, responded enthusiastically to the Yippies’ invitation. In April, Yippie Walli Leff wrote to the band’s manager, John Sinclair, to report that “we’re looking forward to hearing all your Detroit heavy music and are working on getting sound equipment for the Park in Chicago to accommodate everyone who will be playing.”3 Shortly thereafter Sinclair defended the planned festival in a May letter to Jann Wenner, publisher of the recently founded Rolling Stone: “Hope your feuds with Jerry Rubin don’t make you distort the real scene with the Yippies any more. All our bands are planning to make it to Chicago because we’ve been that way all along—ain’t nobody leading us astray.”4 On August 7, the Ann Arbor Sun, a newsletter produced by Trans-Love Energies, the commune in which Sinclair and the MC5 lived, reported that the Yippies had “scheduled rock and roll concerts for each evening and afternoon of the Festival” and that Ann Arbor bands including the MC5, the Up, and the Psychedelic Stooges (as they were then known) also planned to perform.5

As it turned out, the MC5 was the only out-of-town rock band who played in Chicago.6 In his column in Detroit’s underground paper Fifth Estate, Sinclair boasted that “the Fearless 5 was the only group in the whole fucking country to show up and play for their brothers and sisters in the Youth International Party.” (Sinclair acknowledged that Ed Sanders and Tuli Kupferberg of the Fugs, while not performing with their band, were involved in the protests, and that Country Joe McDonald had left town only after some South Carolina delegates beat him up in a hotel elevator.)7 Years later, MC5 drummer Dennis Thompson still felt betrayed: “Chicago was supposed to be the show of solidarity, goddamn it. This is the alternative culture? Come on. Where were all the other bands?”8 Guitarist Wayne Kramer remembered more sympathetically that “there were supposed to be bands from all over the country playing, West Coast hippie bands too, but they had second thoughts about it and, with hindsight, they were right.”9 Many musicians, recognizing the threat of violence if they came to Chicago, maintained their distance. San Francisco’s Jefferson Airplane, for example, declined Hoffman’s invitation to perform in Chicago. As guitarist and singer Paul Kantner later explained: “I appreciate the fact that some people did bother to go there and get their heads kicked in on our behalf, but I couldn’t see any reason for us to go and get beaten up.”10 The MC5, as rock musicians committed to their Yippie “brothers and sisters,” were an anomaly. Although folk stalwarts Phil Ochs and Peter, Paul, and Mary led protesters in song throughout the events in Chicago, rock musicians did not play a major role.11

Lincoln Park, then, hosted not a rock festival but rather a hasty set by a lone, obscure band. The MC5 had to perform at ground level because Chicago police refused to allow the Yippies to bring a flatbed truck into the park for use as a stage, and the band’s Marshall amps (draped with US flags) were powered through a single extension cord that Ed Sanders, reeling from the effects of hashish-infused honey, managed to plug into a refreshment stand’s outlet.12 In his 1970 book Shards of God, a surreal fictionalization of events in Chicago, Sanders depicted the MC5’s “ultra high energy set” as an erotic, life-affirming respite from the tensions of the protest: “on all sides of the stage the prone porn-mammals began to search out and touch one another upon the skin when the godful MC5 began their concert. They sang songs of strong communist realms of banned bras, artisan peace, hemp smoke, communal food, free electricity, and bunch punching. We were happy. Thoughts of mammal-peace filled our minds for a while, replacing the corrosive fear of police tails, Daley, satanism, brutality, clubs, and bullets.”13

But the MC5 themselves were terrified. Kramer, in his 2002 essay “Riots I Have Known and Loved,” insists that “the footage we’ve all seen a thousand times on TV, of demonstrators and police fighting in the streets, doesn’t do justice to the tangible fear. It was an unsettling in the stomach; a gnawing, creepy feeling, like an inescapable cloak of dread. We felt it coming and there was absolutely nothing we could do about it.” As government agents in the crowd of several thousand shot surveillance film of the band, “we played our set, and we could feel the tension building. There were no smiling faces in the crowd.” Once the music ended, “we knew from experience to get our amps and drums packed double-quick for our escape and, sure as shit, the first phalanx of motorcycle cops muscled through the crowd as soon as we stopped playing.”14 For lead singer Rob Tyner, between the helicopters flying overhead, “people who looked like Lee Harvey Oswald walking around with funny-looking packages,” and the paranoia induced by hash brownies, “it was scary, man.”15 Sinclair remembers that as police closed in and Abbie Hoffman “grabbed the microphone, and started rapping about ‘the pigs’ and ‘the siege of Chicago,’” the band made a hasty exit to their van and drove straight home to Ann Arbor.16

Norman Mailer offered a more distanced account in his book Miami and the Siege of Chicago:

A young white singer with a cherubic face, perhaps eighteen, maybe twenty-eight, his hair in one huge puff ball teased out six to nine inches from his head, was taking off on an interplanetary, then galactic, flight of song, halfway between the space music of Sun Ra and “The Flight of the Bumblebee,” the singer’s head shaking at the climb like the blur of a buzzing fly, his sound an electric caterwauling of power come out of the wall (or the line in the grass, or the wet plates in the batteries) and the singer not bending it, but whirling it, burning it, flashing it down some arc of consciousness, the sound screaming up to a climax of vibrations like one rocket blasting out of itself, the force of the noise a vertigo in the cauldrons of inner space—it was the roar of the beast in all nihilism, electric bass and drum driving behind out of their own non-stop to the end of mind.

Mailer, although he found the MC5’s sound “harsh on his ear, ear of a generation which had danced to ‘Star Dust,’” recognized its value to the “Hippies and adolescents in the house . . . a generation which lived in . . . the sound of mountains crashing in this holocaust of the decibels.”17 But not everyone appreciated the MC5’s sonic onslaught. Mailer noted “the sight of Negroes calmly digging Honkie soul, sullen Negroes showing not impressed, but digging, cool on their fringe (reports to the South Side might later be made).”18

If one takes Mailer’s word that the MC5’s Black listeners were “sullen” and unimpressed (he doesn’t seem to have asked them), it is not difficult to propose reasons for their skepticism. Some might have been put off by the Yippies’ presumption in equating the struggles of white radicals to those of African Americans generally, in what historian Marty Jezer terms “an image of hippie-black solidarity.”19 Yippie and satirical journalist Paul Krassner, for example, described the Yippies as “a community of voluntary niggers” in the Ramparts Wall Poster, a broadside distributed in Chicago during the convention.20 While Hoffman had spent years working as a supporter of civil rights groups such as Friends of SNCC and the Poor People’s Corporation, he had recently begun to compare the white counterculture to the people whom he now called “soul brothers” but also, in a willful affront to liberal piety, “spades” and “niggers.”21 Hoffman borrowed his rhetoric about “pigs” and “honkies” from the Black Panther Party, as did the Yippies when they satirically nominated a real pig (“Pigasus”) as the Democratic presidential candidate.22 Hoffman had failed to impress the Blackstone Rangers, Chicago’s most prominent African American “street gang,” who, despite a recent turn toward political engagement, refused to join forces with the Yippies during the convention.23 The MC5’s music and appearance also might have provoked some challenging questions. Why did this white band’s sound evoke the avant-garde jazz of musicians such as Sun Ra, which some Black Power theorists had begun to promote as the soundtrack to Black revolution? Why did the singer style his hair into something resembling an Afro?24 By what right did the MC5 play “Honkie soul”?

In this chapter, I argue that the MC5 did not simply mimic Black music but rather sought to transform it into a new musical idiom suitable for white musicians and radicals like themselves. Rather than attempt literal imitations of the music of James Brown or Pharoah Sanders, the MC5 self-consciously adapted the form and style of their African American influences into a new context. This approach also informed their political stance, which was itself an adaptation, sometimes reverential and sometimes whimsical, of Black Power ideology. The MC5 believed that their commitment to African American music inspired and justified their political activism, but this belief was always threatened by their tenuous position as white performers of that music.

White Panthers, Black Music

The political engagement the MC5 displayed in Chicago has made them familiar not only to rock fans but also to historians of 1960s radicalism. The band is well known today for its affiliation with the White Panther Party, a radical group founded in Ann Arbor in November 1968 from the circle surrounding poet, jazz critic, and arts promoter John Sinclair.25 The White Panthers, whose name signaled their sympathy with the Black Panther Party, claimed to represent a “long-haired dope-smoking rock & roll street-fucking culture” and argued that “rock and roll is a weapon of cultural revolution.” The party’s ten-point program, which blended revolutionary sincerity with sly put-ons in the manner of the Yippies, called for “the end of money,” the freedom of all soldiers and prisoners, free food, clothing, housing, drugs, and medical care for everyone, and “free time & space for all humans.”26 The MC5, who lived with Sinclair and over twenty others in Detroit/Ann Arbor’s Trans-Love Energies commune, became the party’s official band.27 Their first album, Kick Out the Jams, released on Elektra Records in February 1969, featured incendiary liner notes in which Sinclair claimed that “the MC5 is totally committed to the revolution” and an exciting interplay of distorted guitars that many critics and musicians have credited with inspiring punk and heavy metal.28 In 1969, Sinclair was sentenced to nine-and-a-half to ten years in prison for possession of two marijuana joints, a blatantly political persecution that sparked an international activist campaign leading to his release in 1971. Although the White Panther Party emphasized fiery rhetoric more than militant action, by 1970 their notoriety led the FBI to label them “potentially the largest and most dangerous of revolutionary organizations in the United States” and to make them the target of COINTELPRO surveillance.29 Meanwhile, the MC5 broke with Sinclair and the White Panthers and released two more albums to declining sales before they disbanded in 1972.

Even sympathetic chroniclers tend to dismiss the White Panther Party as a prime example of 1960s “fantasy politics,” stoned naïfs whose excesses were matched only by those of the authorities who oppressed them. Popular music scholar Neil Nehring describes the “common view” of the MC5 as that of “a respectable rock band with a laughable pretension to being revolutionary.”30 Historian Jeff A. Hale calls the White Panthers “a group of counterculture ‘freeks,’ who, in search of radical certification, created a largely fictional White Panther Myth—only to end up being portrayed by the Nixon administration as the epitome of a domestic national security threat and embroiled in a landmark constitutional case” (1972’s Keith case, in which the Supreme Court ruled unanimously against the Nixon administration’s warrantless wiretapping of the White Panthers).31 Hale argues that this “myth” centered on a tenuous, self-proclaimed affiliation with Black radicalism: “the sel...