![]()

A CLOSER LOOK AT THE LEGENDS

Even though the historical records are sparse, there is at least some verifiable framework in which to place Derry’s life in early western Pennsylvania. Now it is time to circle back and reexamine the legends about the Witch of the Monongahela within this context. Though these legends have been passed on by word of mouth and in print for nearly two centuries by many different writers and storytellers, they appear to have retained much consistency in their content and form. Still, this does not mean that the legends did not evolve over time and that the context in which they were told did not change. Tales of Moll Derry that were recounted by word of mouth, especially in the early years, are lost to us. These likely included many more stories and accounts of personal interactions that have disappeared or have survived only as a short synopsis or kernel narrative. We are left with only the written record to guide us as to the evolution of the legends. Written sources alone create an incomplete picture when it comes to folklore, but they are all we have. Each of the four main stories from the first chapter has its own set of written sources behind it, but there was one writer who compiled most of these stories in the twentieth century and brought them to a larger audience. Before we examine the background of each legend individually, let us take a brief look at the life and work of the prolific George Swetnam.

George Francis Swetnam was born just outside of Cincinnati, Ohio, on March 11, 1904. His family would move to several different southern states in his youth, and he obtained several different degrees from prominent universities, including the University of South Carolina, the University of Alabama and the University of Mississippi. He earned bachelor’s degrees in English and theology, a master’s degree in theology and a doctorate in Assyriology. During his studies, he learned to speak German and to read ancient cuneiform. Swetnam was also an ordained Presbyterian minister. Throughout his life, he worked at various times as a journalist, photographer, college professor, historian and folklorist. While living in Pennsylvania, he helped to start the Institute of Pennsylvania Rural Life and Culture in Lancaster. In 1943, he settled with his family in the Pittsburgh suburb of Glenshaw and began writing and editing for the Pittsburgh Press. He was known for his articles on the history and folklore of the region and eventually wrote several books, including Pittsylvania Country (1951), which includes an account of Moll Derry. He also served as editor of Keystone Folklore Quarterly from 1959 to 1965. After retiring in 1973, he continued to write occasionally and published additional books. One of these, published in 1988, was Devils, Ghosts, and Witches: Occult Folklore of the Upper Ohio Valley, which again incorporates stories about Moll Derry. Swetnam passed away on April 3, 1999.

Interestingly, throughout the 1960s at least, he also maintained correspondence with several contemporary practitioners of folk magic. It seems this began after he wrote an article about a modern witchcraft practitioner for the Pittsburgh Press. Though the paper generally did not like to run articles on the occult, Swetnam was allowed on that occasion. It seems that this article resulted in him being contacted by several witches who wished to discuss magic and witchcraft in greater detail.

Since Swetnam’s writings in the 1950s and 1980s served as the basis for our modern accounts, we will work backward from these to try to learn what we can about the legends. We will also look at the writings of a few other authors who were key to building the story of Moll Derry and discuss their work as it is reached. Following the same order in which the stories were presented earlier in the book, the legend of the three hanged men will be addressed first.

Though this story is one of the most frequently repeated ones about Moll Derry, Swetnam did not address it in his later writings. However, it was featured in his brief write-up on Derry in Pittsylvania Country. Before looking at his account, it will be beneficial to look at his description of Moll Derry from the same source. He described her as a “stooped, aged hag, of whom all that now remains certain is that she had a ghastly reputation as a witch such as was never attached to the name of any other woman in the Pittsylvania Country.” This statement is interesting for two reasons. First, Swetnam describes Derry in rather sinister terms, firmly framing her as a traditional witch. Second, it is clear that, at least at the time of this 1951 writing, he is unaware of other substantial cases of alleged witchcraft in western Pennsylvania (what he calls Pittsylvania), stating that no other woman had such a reputation. As we saw in the previous chapter, allegations of witchcraft were not as rare as one would suspect, and although none of the other witches developed quite the level of infamy in modern times, they were better known in the nineteenth century. In fact, it can and will be argued as we proceed that it was actually Swetnam who amplified Derry’s reputation as the “lone” witch of southwestern Pennsylvania. This is understandable considering that Swetnam was not a native to the region and was still learning and researching its historical intricacies. Pittsylvania Country was a successful book and can still be found in numerous Pennsylvania libraries and used bookstores. For many people, it was their first (and perhaps only) exposure to the story of Moll Derry.

George Swetnam’s books that include sections on Moll Derry. Author’s collection.

Returning to the three hanged men, Swetnam leads into his account by describing how women who crossed Derry would find that their bread did not rise. The only way to end this curse was to heat and then cool a horseshoe and hang it above the door. He continued, “Legend said, too, that Moll once placed a curse on three men who made fun of her, telling them that all three would be hanged.” The story went on:

One was John McFall, who pulled a tavern door from its hinges in 1795 and bludgeoned the keeper to death in a drunken rage. He was the first man ever hanged in Fayette County. A second was Ned Cassidy, who fled West after a peddler was butchered and sunk in a millpond in 1800. In Ohio he murdered another man and was hanged. But first he signed a confession to the murder of the peddler, which was mailed back to Uniontown by those who hung him. The third, whose name is not preserved, went to Greene County and hanged himself in a fit of despondency, according to the legend.

As one can see, this is essentially the story as it is told today. This account was reproduced almost verbatim in a 1972 article by Joseph G. Smith in Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine. Titled “Ruffians, Robbers, Rogues, Rascals, Cutthroats, and Other Colorful Characters,” the article reintroduced Derry to new readers and added a layer of academic credibility to Swetnam’s account. In 1976, the Uniontown Morning Herald ran an article on witches in Fayette County, and the story was repeated again in a shorter form.

One of the frustrating things about Swetnam’s writing on Moll Derry is that we do not always know what his direct sources were. Two different collections of his personal papers have survived and are publicly accessible, and although they include much of his research, neither contains his documentation on Moll Derry. It is likely that he drew most of his information from old local histories and newspaper articles, as well as from interviews with people who heard the stories growing up in Fayette County.

Wherever Swetnam got his information, it is clear that the story was in circulation for a long time. A fictionalized version appeared in Alonzo F. Hill’s book The White Rocks: or, The Robbers’ Den. A Tragedy of the Mountains. Hill’s book is a fictional version of the story of Polly Williams and her murder. In this version, Moll Derry is given the name Molly Pry. Though she was deceased by the time of the book’s publication in 1865, her children were not, and that is why many believe the name was changed. In fact, many historical figures in the book have their names altered. In the discussion of Molly Pry that occurs between Mary (Polly) and her cousin Tilly, the story of the hanged men comes up. When Tilly mentions that she would rather not run into Moll Pry, Mary asks:

“Why so? She was never known to harm anyone.”

“No, not directly; but if she predicts evil of any one it is sure to come to pass; and that is what I should fear—that she might say some horrid things of my future. Three men once, of the names of Butler, Dougherty and Flanigan, of whom you have no doubt heard—”

“Yes, I have heard of them.”

“Well they were up in the mountain after chestnuts, and they met old Molly, and provoked her in some way, and she cursed them, and predicted that they would all be hung before a year. She came pretty near the truth, if not quite. Butler was hung for killing and robbing a drover before six months—the only man ever hung in Fayette County; Dougherty shot a man over in Greene County, and was hung by a mob before the year was up, and Flanigan, about the same time, murdered his wife with an ax, and ran away to escape justice. It is not known positively that Molly’s prediction was verified in this case, though it has been rumored that he fled to Ohio, and shortly after, in a crazy fit, brought on by drink, hung himself in a barn.”

“I have heard of those men, and of their deeds, but I was not aware that old Molly warned them of their fate.”

“She had though; for they stopped at our house on their way home and took dinner, and they laughingly told father of their adventure with the old woman, how they had teased and taunted her to hear her swear, and how she had prophesied that they should all be hung before the chestnuts should be ripe again. It was ten years ago, and I was quite young then, but I remember it distinctly.”

Hill’s account is more detailed than most but is also very different. This is of course due to the fact that many of the names of actual individuals were changed in the book, though their general stories remain fairly accurate. Aside from the different set of names and the differences in details of the crimes, the core of the story is still the same—three men taunted her and she cursed them to hang. Her prediction came true. Hill added the final part as firsthand confirmation of Moll Pry’s (Derry’s) power to emphasize the importance of her subsequent prediction to Mary/Polly. We will return to Hill’s account when we discuss Derry’s part in the story of Polly Williams.

Before Hill’s fictionalized version, it does not seem that we have any surviving direct written accounts of the story of the three hanged men. It is possible that Hill fabricated the story for dramatic effect, but that does not explain the different set of names used in most accounts. Generally, Hill adapted local happenings in the book, so there is just as much of a chance (if not more) that Derry’s curse on the men was an authentic part of local folklore. So now we must ask—what, if anything, do we know about the men mentioned in the story?

In all but Hill’s account, the first of the men to face the noose was John McFall. Luckily, there is historical information available about McFall, who was a real person. He really was the first man ever hanged in Fayette County. Early on the morning of November 10, 1794, McFall murdered innkeeper John Chadwick in Smithfield. The two had been arguing earlier when McFall threatened to kill a constable named Myers (who had previously arrested him) inside the inn. When Chadwick intervened, McFall threatened him too. Myers decided to leave and went outside to his horse. McFall followed him out and continued arguing. When Myers rode off, he tried to return to the inn, but Chadwick would not let him back in and ordered him to go home. Feigning acceptance, McFall shook his hand and walked away. Only minutes later, he charged back to the door and tore it off its hinges. He grabbed Chadwick, dragged him outside and proceeded to beat him with a club until his skull was cracked. Chadwick clung to life for almost two days before dying in agony.

A photo of the old Nixon Tavern near Fairchance taken in 1934. This tavern was similar to the tavern in Smithfield where John McFall murdered John Chadwick. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

After the murder, McFall fled to Virginia, but he was captured and returned to Uniontown. He was quickly put on trial and convicted of first-degree murder. His sentence was death. Before it could be implemented, he escaped from prison but was apprehended again near Hagerstown. In May 1795, he was hanged in a clearing near Redstone Creek close to Fairchance.

Ned Cassidy, the second man, was also a real person. We will return to him and his associate John Updyke shortly when we discuss the legend of the murdered peddler. For now though, we can confirm that he did help murder the peddler sometime after 1800, fled west to somewhere in Ohio and committed a second murder. Before he was hanged for that murder, he wrote a confession to the peddler’s murder that was sent back to Fayette County (at least according to the 1882 History of Fayette County).

So that brings us to two confirmed hangings. Unfortunately, all of the accounts aside from Hill’s fictionalized version never name the third man. There is no way to verify whether this individual really traveled to Greene County and hanged himself. It seems that if Derry really did curse the men to hang as the legend claims, then at least part of what she predicted came to pass. Of course, there are no early historical sources that document her interaction with the men. But it would be highly unusual for such an occurrence to be written into a history book in the 1800s. This leaves open the possibility that it did occur. It simply may have been a neighborhood dispute that took on legendary status due to the individuals involved and the seemingly accurate nature of Derry’s predictions. After all, an argument between an alleged witch and several shady characters would not likely be forgotten.

Of course, another possibility is that Hill did fabricate or exaggerate the encounter for his book and later writers assumed it was based on a real account. They may have tried to figure out who the real figures were and assigned McFall and Cassidy to the roles. While this is possible, it seems unlikely, because Hill makes the point that “Butler” was the only man ever hanged in Fayette County. At that point in time, McFall was still the only man to be hanged in Fayette County, and his story was well known. It seems that Hill was just letting the reader know exactly who Butler was supposed to represent, considering he changed details of the crimes. One could argue that it is possible that Hill used known criminals as the inspiration for the characters but still made up the encounter with the witch. That, too, is a possibility, but he did rely heavily on local folklore throughout his account. Given Derry’s reputation, it seems likely that there was some kind of dispute that the encounter with the three men would have been at least loosely based on. Unfortunately, unless an earlier written account of the legend turns up in the future, we will never know for certain.

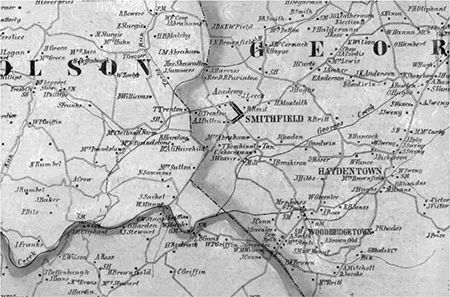

A closer look at the related legend of the murdered peddler yields no more definitive information than that of the three hanged men. Swetnam wrote about Ned Cassidy and the murdered peddler in Devils, Ghosts, and Witches. This was his final writing on Derry, but the details are somewhat different from what would be expected. Cassidy’s name is now spelled Casedy, and the year of the murder is changed from shortly after 1800 to “the late spring of 1818 or 1819.” According to Swetnam, a peddler from New Jersey visited a tavern kept by Nace Kyle. There he met John Updyke, who was also originally from New Jersey and happened to be an old acquaintance. Updyke invited him to his house, and though he initially hesitated, the peddler agreed to go. Along the way, they met Updyke’s friend Ned Casedy and decided to have a few more drinks. They passed by Updyke’s home outside of Smithfield, near Ruble’s Mill, and walked to Haydentown to drink whiskey. Then it was decided to travel to Moll Derry’s dwelling to a dance. Why a dance was occurring at Moll Derry’s house is not explained, although perhaps it had to do with her sale of whiskey. It was also emphasized that she was a fortune teller, implying that the peddler might want his fortune told. The three men left, but instead of going to see Moll Derry, Updyke and Casedy took him back toward Updyke’s home. Somewhere along the way, the pair attacked and murdered the peddler. The next morning, a man named Robert Brownfield found a bloody handprint near Updyke’s home and followed a trail of blood across Robert Collin’s farm to the hill above Weaver’s Mill dam and pond. It is presumed the body was found in the pond at some point, but it is not explicitly stated. Suspicion immediately fell on Casedy and Updyke, but neither was arrested in spite of the circumstantial evidence.

An 1858 map of Fayette County depicting the area around Haydentown and Smithfield. Weaver’s Mill is visible on the map. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Shortly after the murder, Updyke became ill. One day, a “respectable citizen of George” named Valentine Moser was visiting Updyke’s neighbor Hannah Clarke. Clarke was known locally as a witch, and when Moser arrived, she showed him a drawing on the back of her door. It was an outline of John Updyke, with a nail tapped into the side of the head and one at the left temple. She explained that if she drove the nails into the drawing the entire way, Updyke would die, but instead she tapped them in a little every day to torture him...