![]()

1

VISIONARIES

Henri Nestlé, Daniel Peter and the People of Fulton

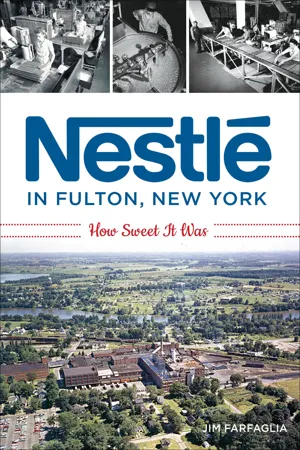

Fulton was ready. When businessmen from Switzerland’s Nestlé Food Company came to the United States in 1898, searching for a site to build their first factory on this side of the Atlantic, the people of Fulton put their best foot forward. Nestlé wasn’t in the chocolate-making business yet, but the company had established itself throughout Europe as a leader in the production of infant milk formulas and sweetened condensed milk. Ready to expand their successful business, company officials were looking for a location in America that could match the abundant dairy resources in their Swiss homeland, and New York lawmakers made sure their upstate farms would be in the running. The Nestlé dignitaries were directed to two industrial towns that were soon to merge and become the city of Fulton.

Though it would be four more years before Fulton’s official incorporation, local leaders were already planning how the city would take shape. The two towns destined to become one—Fulton on the east side of the Oswego River and Oswego Falls on the west—had made their consolidation plans known to New York State policymakers. When the state’s senator Nevada Stranahan had been informed of that fact by prominent Fulton resident George

C. Webb, the two men collaborated on an offer to the Swiss gentlemen searching for their new factory’s home. Hopeful news travels fast, and soon the possibility of a visit from such special out-of-towners traveled back and forth across the river. People on both sides agreed that a new industry was just what was needed to unite their new city.

Competition for being selected as Nestlé’s first U.S. factory was stiff, but the Swiss visitors would find plenty of incentive to choose Fulton. The Nestlé Company had already decided the new factory should be located on the East Coast, where several densely populated cities were already thriving. Boston, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., and New York City were all a day’s travel from upstate New York and Fulton’s ability to deliver to those metropolises had already been established. Factories in the two towns regularly used both the Oswego River, which was part of the New York State Canal System, and several railroad companies to distribute their wares. Industry-driven business was so good in the Fulton area that it spurred the growth of smaller support companies, grocery stores, churches and speakeasies. When the two towns merged, their new city was rich with potential.

The local and New York State officials wooing Nestlé’s Swiss businessmen had an even more important selling point to offer. The visitors were given a tour of an important industry operating just beyond the two towns’ borders: dairy farming. Miles of meadowland in the largely rural Oswego County, where the soon-to-be city of Fulton was located, had long provided sustenance for farmers’ grazing cattle. Indeed, when Nestlé officials arrived in upstate New York, the principal occupation in the area was farming, much of it dairy-related. The 1900 New York State Census recorded the county of Oswego as maintaining 6,526 farms with domestic animals, 41,000 of which were listed as “dairy cows two years or older and giving milk.” On average, those cows were producing 300,000 gallons of milk a day, an impressive number to Nestlé.

Evidence of a strong dairy industry was everywhere in the Fulton area. In addition to established farms, it wouldn’t have been unusual for cows to be seen grazing in the yards of residents within the two town’s borders. (One person I interviewed remembered the days when every home in the Fulton area had at least one cow.) Any milk not sold for consumption was sent to local cheese factories; the closest two were located in Granby Center and Bowens Corners. Yes, the Swiss found plenty of milk in Fulton, but it wasn’t just abundance they were looking for.

All those farms within horse-drawn carriage distance of the potential factory site were producing milk that was considered among the highest quality in the northeastern United States. By grazing in bountiful meadows, Fulton-area cows gave milk with a high percentage of butterfat, providing the richness Nestlé demanded for its products. After all, the company’s success had been built on the milk from cows fed by Swiss mountain meadows, and the visitors were pleased to see lush farmland reminiscent of their homeland. The company’s founder, Henri Nestlé, would have been pleased as well. Long before his company chose Fulton to expand its milk production success, Henri Nestlé had devoted his life to turning the highest quality milk into a lifesaving new product.

HENRI NESTLÉ

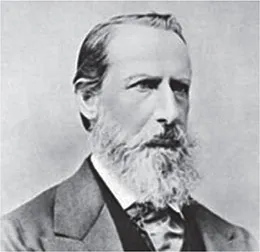

Three decades before the Nestlé Company learned of Fulton’s abundant milk supply, Henri Nestlé was working day and night in his Vevey, Switzerland home laboratory. Already a successful chemist and pharmacist, Henri was among a handful of medical researchers attempting to find a solution for a health crisis in his homeland and beyond. Throughout Europe, families were being cruelly affected by a high infant mortality rate; in fact, in Switzerland, one in five children died before his or her first birthday. Nestlé, among others, was experimenting with a food product that would one day be advertised as “fresh as milk straight from the cow’s udder,” a quality largely unavailable in Europe’s overcrowded cities.

One might say that Henri Nestlé’s conviction to solve this problem for young families flowed through his veins. As the eleventh of fourteen children in a close-knit German family, Henri knew firsthand of the struggles to provide adequate nourishment for loved ones. In his youth, family was all Henri had, and he never forgot it. As a successful businessman, when it came time to create an image to promote his milk production company, Nestlé looked no further than his German surname, which in English means “a small bird’s nest.” Using the Nestlé family’s coat of arms—three baby birds being fed by their mother in a nest—Henri created his company’s famous logo. When the lack of sufficient food for young children became a crisis, Henri Nestlé accepted the challenge to overcome it. One night in September 1867, engrossed in his research, a knock on the door intensified that challenge.

It was a colleague of Henri’s who’d arrived with some upsetting news. Years later, he remembered their conversation: “[The man told me that] Mrs. Wanner was seriously ill, as was her child, born a month too early. At fifteen days old, he was a sickly infant who refused not only his mother’s milk, but all other types of food as well. He was convulsive, and there seemed little hope for him.”

Already years into his experimentation with milk byproducts, Nestlé had had some success combining cow’s milk, grain and sugar to create a balanced substitute for what nursing mothers normally provided. Using this dough mixture and his secret formula (so secret that his company has never revealed it), Nestlé baked it, broke it into pieces, ground it in a stone mill and packed it in tin cans. By the time he heard a knock on his door, Nestlé had marketed his product, calling it Kindermehl, or “Children’s Flour.” But his formula had never been tried on a young infant. Could Nestlé’s creation come to the aid of Mrs. Wanner’s gravely ill child? There were no other options. The child was dying.

Henri Nestlé the Swiss-born entrepreneur, founded his famous company after developing a lifesaving milk formula for infants and children. Google photos.com.

“After being fed my formula, he began to thrive,” Nestlé recounted years later. “After seven months, having eaten nothing but this formula, he has never been ill and is now a tough seven-month-old who can sit up all by himself.”

It was a miracle indeed. Mrs. Wanner’s baby not only lived but also flourished as any normal child. Word of Nestlé’s success passed from hopeful mother to caring doctor to savvy businessman, and by 1868, Nestlé’s infant cereal was selling throughout Europe. Demand for the product was also created by women of higher social standards who considered breastfeeding “unfashionable.” Henri’s one-man operation soon mushroomed into a factory in Vevey and then several others in nearby countries. By 1875, Kindermehl was available in nearly every major country in the world, selling a half million cans a year.*

After his contributions to the health and well-being of children became a resounding success, Henri Nestlé was ready to free himself from the demands of his rapidly expanding business. When buyers came forward with an offer, the sixty-year-old entrepreneur relinquished full ownership of his business, even rejecting the option to retain partial rights as a shareholder. Though Nestlé’s new CEOs wisely kept the founder’s name for their company, their nutritious product was newly branded Farine Lactée, or “Flour with Milk.” Despite his name forever being associated with the food industry, Henri Nestlé never again participated in its worldwide success, choosing to share his considerable wealth with the people of his hometown. Nestlé died in 1890, ten years shy of seeing his life-sustaining infant formula provide a hearty boost for the newborn city of Fulton.

DANIEL PETER

Henri Nestlé made one more important contribution to Fulton commerce, one that would prove even more influential than his milk products. However, our city would have never benefited from this other gift from Nestlé if someone in his own backyard hadn’t received it first. Right around the time Nestlé was closing out his successful career, his next-door neighbor, Daniel Peter, was just beginning to experiment with a new food product. Though the food, a chocolate bar, may not have seemed as vital as Nestlé’s milk products, young Peter was working as feverishly as his elderly neighbor once had, desperate to figure out how to launch a business that would save his financially strapped family.

Things hadn’t always been so tragic for Daniel Peter. Born in a Swiss mountain town in 1836, Daniel’s inquisitive mind had made him an outstanding student, so much so that, by age nineteen, he was teaching Latin to his peers when their professor took ill. His drive to succeed continued beyond the classroom, and by his twentieth birthday, Daniel was already operating a candle factory with his brother. Candles were the only available source of artificial light at the time, and the Peter brothers were confident that they were financially set for life. Then, in the late 1850s, kerosene was introduced as a fuel for more modern means of lighting, and within a decade, the candle industry had collapsed. In debt and any hope for success all but extinguished, it would take love to rekindle young Daniel’s determination.

The building that housed the Peters’ now-obsolete candle factory was owned by François-Louis Cailler, the patriarch of a successful chocolate candy business. Cailler’s daughter, Fanny, caught Daniel’s eye, and just as his candle-making business was ending, the two fell in love and married. Without a means to support his bride, Daniel approached his new fatherin-law, proposing that he join Cailler’s booming business. He was flatly rejected, and perhaps it was his in-law’s crass denial that drove him to a new business idea. Instead of joining Cailler’s chocolate company, Daniel set out to become its competitor.

The chocolate-making industry had rapidly grown and diversified since it first became a viable business in 1818, when Mr. Cailler adapted a flour stone mill to crush cocoa beans, mixed them with sugar and produced his candy bars. In the early years of Callier’s chocolate production, the bars were not considered a confectionary treat but rather a compact source of nutrition for those required to exert great physical effort. They were the energy bars of their day, but they were bitter, and in an attempt to widen their marketability, chocolate makers were tinkering with the recipe. Some added more sugar, which only made the chocolate overly sweet. Daniel Peter had been observing the evolving chocolate industry, and his keen intellect had him pondering a third ingredient that could somehow mellow a candy bar’s bitter and sweet qualities. But what ingredient would produce the desired balance?

The explanation of what happened next for Daniel Peter is something I call a legend, since no one alive today or the results of my research can verify that it actually took place. However, since several people I interviewed mentioned the following story and there are discrepancies in various profiles of Daniel Peter’s groundbreaking work in the chocolate industry, I am including it for consideration. Here’s how the story goes:

Over the fence that separated their properties, next-door neighbors Daniel Peter and Henri Nestlé carried on a conversation about how Peter might break into the chocolate candy market. While discussing what could set his candy bar apart from all others, Nestlé suggested: “What if you added my milk to your chocolate?” Peter liked his neighbor’s idea enough to begin experimenting.

Was it really that simple? Was Nestlé’s suggestion all it took to inspire Daniel Peter to radically change how most people would thereafter consume chocolate? Some who have written about Peter’s innovative chocolate bar claim that he had already been contemplating adding a dairy product to chocolate and was merely discussing the pros and cons of it with his neighbor. No one knows for sure how Daniel Peter took his first step toward creating milk chocolate, but once he was convinced the idea had merit, he became as driven to succeed as Henri Nestlé.

Peter would need that drive once he started running into the many problems of using an ingredient as perishable as fresh milk. It was only years later, after experiencing phenomenal success with his milk chocolate bar, that he was willing to talk about his early experiments and failures:

My first tests did not give or produce the milk chocolate as we know it today. Much work took place and after having found the proper mixture of cocoa and milk…my tests, I thought, were successful. I was happy, but a few weeks later, as I examined the contents, an odor of bad cheese or rancid butter came to my nose. I was desperate, but what was I to do?… Being as it was, I did not lose courage, but I continued to work as long as circumstances allowed.

And persist Daniel Peter did. For the next eight years, he struggled, much like Henri Nestlé had, working to ensure that his milk chocolate bar could sustain a long shelf life. While Nestlé was able to advise his neighbor on how to deal with the perishable fat in milk, Peter had the added challenge of the high fat content in cocoa beans, which makes up about half of a bean’s composition. His problems didn’t end there. Peter’s tests soon revealed that fat does not mix well with liquid, and his special ingredient, milk, is 88 percent water. With each new discovery, Peter’s goal seemed to be more unreachable. It would take every one of those eight years of experimentation to figure out his solution.

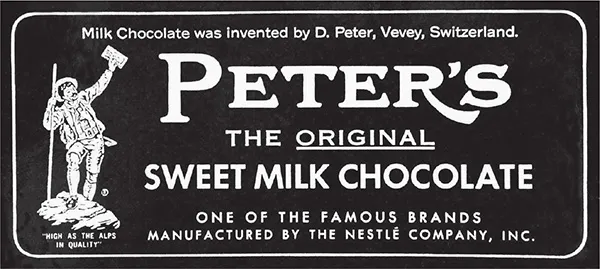

Daniel Peter’s creation, the milk chocolate bar, became hugely popular in the United States once the Fulton Nestlé plant started producing them. Fulton Nestlé archives.

As a first step, Peter turned a small space of his home into a “drying room,” where milk could be evaporated and turned into flake form. Next, he developed a machine that could extract fat from his chocolate mixtures. He tinkered with the process, attempting to remove just the right amount of fat to avoid premature spoilage while retaining enough of its pleasurable taste. At times, the endless trials overwhelmed Peter, but there was one thing he and his taste testers could not deny: after one bite of his milk chocolate bar fresh off the production line, people were proclaiming it a confectionary sensation.

This logo was used to promote Daniel Peter’s original Swiss milk chocolate bars. It was also featured on candy bars manufactured at the Fulton Nestlé factory. www.peterschocolate.com.

By 1875, Peter had perfected his product, calling it “Gala Peter,” using the Greek word for milk, Gala, to distinguish his candy bar from competitors. The chocolate bar began appearing on market shelves in a copper-trimmed wrapper, promoted as “the first milk chocolate” and “the healthiest of all chocolates, very nourishing, very digestible, a little sugar not causing thirst.” Included on the wrapper were these words: “High as the Alps in Quality,” reflecting Peter’s Swiss roots. His chocolate bar pledge sounded a lot like Henri Nestlé’s promise to provide life-giving milk products for children, and together those commitments would one day be carried out by thousands of workers at the Nestlé factory in Fulton.

In the January 1916 issue of International Confectioner, reporter T.B. McRobert had much praise for Daniel Peter, referring to him as “the inventor of milk chocolate.” McRobert had been covering the rising popularity of milk chocolate bars in Europe and noted that “in 1892, when I spent a number of months in Switzerland, not one of the other Swiss chocolate manufacturers—and I visited them all—made it.” Fame followed Daniel for the rest of his life, and he earned awards and proclamations for his i...