![]()

1

THE SECRET INSTITUTION

I must go with him to another part of the woods where there was a certain root, which if I would take some of it with me, carrying it always on my right side, would render it impossible for Mr. Covey or any other white man to whip me.

—Frederick Douglass

The practices of rootwork and conjure were born out of the healing and spiritual traditions of Africa. These rich traditions were kept alive in secret amid the abuse and violence of slavery. As slaves were brought into the Delta and families expanded through the Mid-South, the practices that aided in their survival began to pour over into the public’s eye. What was once hidden in plain sight was being observed by outsiders, who, in most cases, ridiculed and shunned the practices, while a segment of nonpractitioners feared, respected and sometimes even used these traditions.

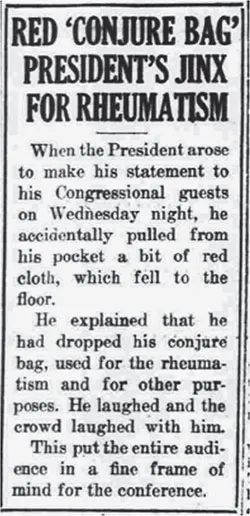

The culture of hoodoo was so prolific throughout African American communities throughout the United States that its practices even garnered the attention of the president of the United States. In 1919, Woodrow Wilson stood before Congress, and as he was reaching into his pocket, he accidentally dropped a piece of red cloth. The president explained to the members of Congress and the press that he had dropped his “conjure bag” and that he kept it to help his rheumatism and other problems. Wilson chuckled, as did the members of Congress. While the concept of the “conjure bag” was being laughed at, it also became apparent that hoodoo had made quite an impact on the consciousness of the country. The once-secret institution of healing and magic was no longer a secret.

As the practices of Africa and African Americans began to be revealed in southern society, they also continued to be feared and demeaned. Reactions found in Mid-South newspapers from Kentucky, Mississippi and Tennessee and carried in other papers nationwide starting in the early 1920s were quite alarming:

Hoodoos or African Witches are operating in Boyle County with frightful results. Seven colored citizens have already been driven to the mad house by the alleged satanic influences of the hoodoos. [Kentucky Advocate (Danville, KY), May 7, 1925]

Devil Worship still exists. Voodoo Practices Originating in Africa, Have Not Lost Their Hold Among Negroes in America. The witch doctor business thrives among the Negroes of the South and to some extent to the North. It is a kind of magical art called Voodoo and came originally from Africa. For a moderate price you can buy a “hoohoo” packet from a voodoo woman that is guaranteed if fastened to his front gate inconspicuously to cause your enemy to sicken and die. It contains such articles as bits of bone, a tooth or two feathers. [Cuba (KS) Daylight, March 21, 1918]

Rumblings of African mumbo-jumbo were heard in the juvenile court as a delegation of Negroes came here from Athens Tennessee to protest holding of a negro girl named Susie. The delegation told Judge L.D. Miller that Susie paroled from the state training school recently was “doing well” and that charges against her were “conjured up by dat ol’ hoodoo.” [Corpus Christi (TX) Caller-Times, August 27, 1937]

The practice of traditional healing and conjure was frequently looked on as foolish superstition by those outside of the African American community in the Mid-South. Traditional practices that had been performed for years were often mocked in the public eye. Newspapers sharing reports of African American folk practices would typically describe them in a condescending and racist manner. A 1906 news story in the Natchez Democrat out of Natchez, Mississippi, shared the sentiments of many white southerners at the time. The article, “Forty Years of Freedom: Negroes Retain the Foolish Idea as to the Power of the Conjure Bag,” said:

Mr. Austin Smith, owner of Saragrossa plantation, this county, drove into the city wearing a most amused smile on his always beaming face and when questioned as to the whenceness and whereof for the smile, he said “Forty years of freedom have not been enough to eradicate the idea from the negro’s mind that the conjure bag is the only thing that will keep the witches off, or break a hoodoo.” Saying this he extracted from his pocket a conjure bag that one of the negroes on his place had dropped. It was a red flannel concern, wrapped with seven pieces of string and contained a piece of silver, a bit of graveyard dust, a piece of lodestone and some hair from a graveyard rabbit’s leg. The string was wrapped around the bag so that it left a long loop over the wrist, and the owner of the bag would hold the bag in the hand while shaking hands with the person they wish to conjure. In case of driving witches away from the house the negroes wave the bag above the head [and] indulge in some kind of monologue that is beyond understanding.

News of the “pagan practices” of African folk healing and culture became a popular topic among members of the wealthy upper class. Traditions were viewed as “devilish” and at the same time “exotic” to those outside of the culture. Newspapers in northern states ran articles about the “Southern Negro” who participated in “wild” African rituals. Following a high-profile incident in Montgomery, Alabama, involving a member of an African healing culture, the Montgomery Advertiser spoke of how “a shabby, smelly room on Montgomery’s Monroe Street could just have easily been a thatched hut in the jungles of Haiti and the ‘witch woman’ who practiced her voodoo rites over a smelly brew could have readily been a sorceress of that Island of Black Magic.”

In 1915, a group of politicians gathered in the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York to listen to an animated Tennessee judge named Benjamin Franklin Adams as he discussed southern culture. The conversation drifted into the topic of hoodoo and “conjure bags” in the South:

What I have noticed hereabout don’t even know what I mean when I speak about a conjure-bag. A conjure-bag is like one of those things like potlicker and crackling-bread which can only be made by an expert. It is considered extremely efficacious among the colored population of our section of the country, and not a few of the poor whites pin their faith in it. If you put it where your enemy has to step over it, it will deprive him of the use of himself and you can bring upon him any kind of evil fortune. In the preparation of a conjure bag as well as its use. The strictest secrecy must always be observed. Should the intended victim discover it, he can convert it to his own uses by simply putting it into running water. The owner of the bag will then go crazy.

The judge went on to talk about the work of a rootworker in Brownsville, Tennessee, known as Aunt Phoebe Thompson. Aunt Phoebe was well known for making powerful mojo bags. The judge described to an interested audience the ingredients of local mojo bags in West Tennessee: “I should explain gentlemen that some of the ingredients that go toward the making of every real conjure bag besides those requisites I have mentioned a crow’s foot, a snake bone, some yarn and string with has been dyed with some copperas, some game rooster blood and various other components of less importance, but still necessary.”

While Hoodoo and African American folk practices were frequently mocked as foolishness by those outside of the black community, these practices were often perceived as posing a threat to communities.

The prevalence of hoodoo throughout North America caught the attention of a U.S. president. Woodrow Wilson joked with Congress that he carried a “conjure” bag for his rheumatism. Courtesy of Washington Times.

For example, in 1908, a courtroom in Little Rock, Arkansas, became frozen in silence as a young black man stood before a jury. Louis Hursch had been brought in as a suspect in the murder of a local farmer. The farmer, Sam Haywood, had been called to his doorway by an unknown subject. When Haywood approached the threshold of his home, he was struck by a gunshot.

As the accused suspect, Louis Hursch stood quivering in front of the courtroom. The jury listened to his testimony, and as the court’s proceedings came to an end, a member of the jury stood to his feet. The juror demanded that a test be performed on the murder weapon to ascertain if the gunman was indeed guilty. The African American jury member requested a “folk” test that had become popular in the local black community. The court would run a “voodoo test” to see if the man was guilty. The test involved firing the weapon; any evidence of guilt would manifest in the form of blood on the barrel of the gun. The jury member claimed that a gun used to murder would “sweat blood at the muzzle.” The gun was fired, and a strange red color was observed at the end of the gun’s barrel. Upon seeing the appearance of the symbol of guilt, Hursch pulled out a knife and plunged it into his own throat. Unfortunately, the red residue on the gun was later determined to be rust.

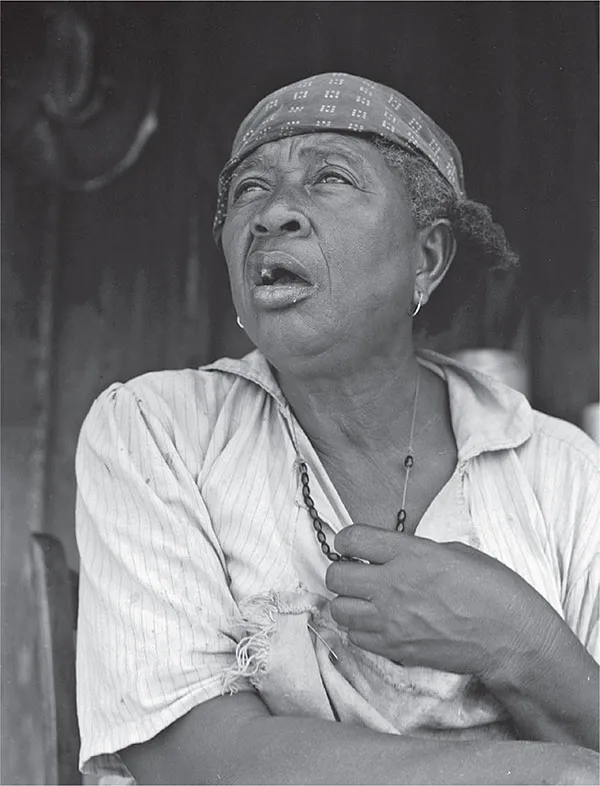

Evidence of early spiritual tools in the Mid-South. This 1937 photograph shows a Mississippi sharecropper wearing a black beaded necklace believed to protect against heart problems. Courtesy of Farm Security Administration—Office of War Information Photograph Collection. Library of Congress.

THE HOODOO BOOGEYMAN

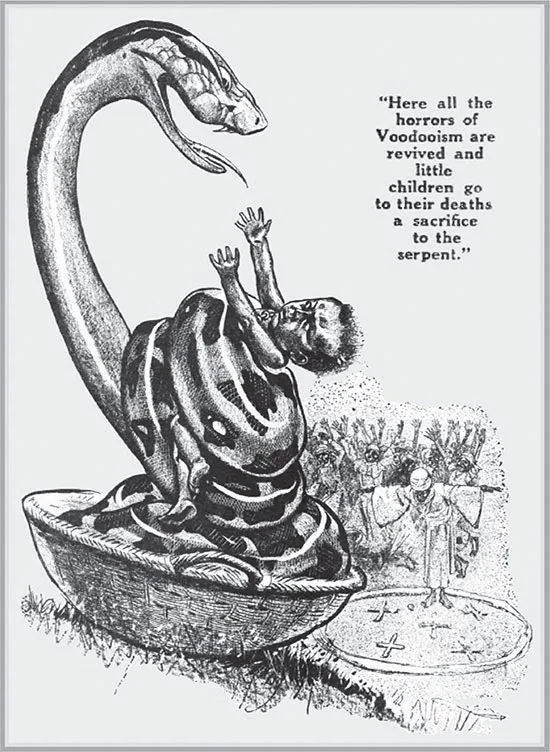

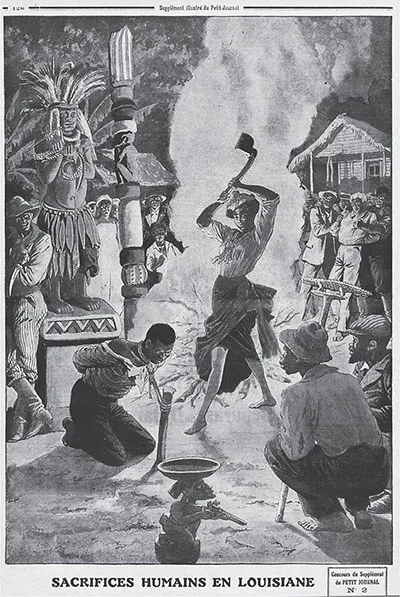

Many communities in the Mid-South were quite frightened of African American healing and spiritual cultures. This culminated from a mixture of racism, bias and fear stemming from myths about race and culture. Mythical stories and misinterpretations of religion that came out of New Orleans seemed to set the stage for the paranoia and fear of rootwork and conjure in the Mid-South. New Orleans was often looked on as the “mecca” of hoodoo, voodoo and African “pagan” practices. Media reports seldom accurately described the African diaspora in Louisiana, instead focusing on sensationalized reports of animal and human sacrifice, zombies and curses. The potential for African religion to bond its devotees was often feared by slave owners. In some cases, practitioners were punished for merely practicing traditions.

Fifteen Negro men and women were arrested in New Orleans last week for participating in the African Voudou dance. When taken they had images placed around the room as is the custom in Africa. They were ordered 50 lashes each. The dance is most obscene and brutal.

This was not restricted to the Mid-South. A 1901 public report regarding lynchings in Illinois listed a number of crimes that had been punished by lynching, including murder, arson, rape and “voodooism.”

National newspapers featured headlines such as “Secrets of Vicious Voodoo Doctors Who Victimize Gullible Girls.” The “Voodoo Boogeyman” in the South was slowly created by stories like this one from an 1870 publication:

Newspapers across the United States carried stories about the presence of African-based cultures in the Mid-South as well as the many urban legends surrounding traditional cultures. Courtesy of El Paso Herald.

New Orleans is just now greatly excited over the sudden disappearance of a white infant child belonging to a Mr. Digby who is believed to have been stolen by a negro woman for the purpose of sacrifice on a voudou altar. Constant and unremitting search has been made without success, not withstanding heavy rewards have been offered for the recovery of the child. No one appears to feel authorized to say it was stolen for sacrificial purposes, yet the thousands believe such was the case of its abduction.

Legendary Vodou queen Marie Laveau became the ultimate “boogeywoman” as the Mid-South caught wind of stories about her from local and national media. Ominous headlines, like this one out of Nashville, Tennessee, in 1930 warned, “Black Shadows of Congo Gods Hover over Snug Cottage in New Orleans. Large Salt Cross, ‘Gris-Gris’, a Voodoo Curse Appears on Front Porch.”

As a result of the large number of African traditions in New Orleans, many cities in the Mid-South feared that any evidence of African culture would turn their communities into similar entities. Most myths and legends surrounding New Orleans focused on tales of human sacrifice and black-magic rituals. Courtesy of author’s collection.

Reports of spiritual workers from the Mid-South who performed spiritual readings and healings in New Orleans brought about suspicion of these specialists importing destructive activities back into the Mid-South. In 1889, Mississippi-born spiritual healer James Alexander was arrested in New Orleans for disturbing the peace. Alexander was believed to have a spiritual power, as he was born with a caul or “veil” over his face that signified his special abilities. He was arrested as part of a party of men and women who were engaged in dancing and loud behavior. The spiritual healer told police that he was in the process of providing treatments for several clients as neighbors complained about the loud shouting coming from the building. Accounts tell of dancing, shouting, spiritual treatments and men and women dressed in loose clothing. Many of the same characteristics would be found in a number of the diverse African healing and spiritual traditions throughout the Mid-South.

As Mid-South communities began to see African folk practitioners as invading enemies, threats of violence began to rise with reports out of cities like Memphis of local citizens assaulting rootworkers. Law enforcement in cities like Memphis and Montgomery began a series of campaigns that included mass arrests, undercover operations and rounding up of spiritual workers in black communities. Lest it be thought that using terms like war are this author’s personal description of these campaigns, it should be understood that this was the terminology used by communities and agencies engaged in these campaigns. Memphis newspapers ran headlines like “Voodooism Called Plain Racket by Warring Tennessee Police,” while an Alabama newspaper announced, “Detective Wages War on Black Magic Here.” It became very apparent that there was a definite agenda in the attack on African traditions.

HEALTH CARE AND ROOTWORK

Rootworking practices were frequently met with dismissal and in some cases disdain by not only the law but also those in the medical field. African healing techniques in areas like Louisiana in the 1940s were blamed for the spread of diseases and hinderances to preventative care. Issues like the growth of syphilis in African American communities was blamed on indifference from the rootworking community. Spiritual healers were frequently referred to as “quacks” and “witch doctors.” Louisiana state officials warned the outside community about African practices. A report from the Works Project Administration’s (WPA) Venereal Disease Control Project warned: “We know of a number of instances in which negroes have paid from one to fifty dollars to voodoo doctors for charms to ward off evil spirits. In most instances, the charm better known to the victims of the voodoo doctors as the ‘hand’ usually consists of a bag filled with a concoction of crushed bone, peach seeds, frog stools and other ingredients. This bag they wear around the neck. Sometimes the treatment of the voodoo doctor is accompanied by chants in an unknown tongue and by dances and other primitive maneuvers.” Along with ethnocentric descriptions like “primitive,” health departments began to post signs and posters featuring images of rootworkers, warning the public of their “dangerous” practices. One particular poster featured a group of African American men sitting around a boiling cauldron while a “witch doctor” presided over a healing ceremony. The “witch doctor” in question was actually a local New Orleans healer who had been photographed preparing a mojo hand. The WPA would go on to have several interactions with African and African American spirituality, including the collection of testimonies of former slaves and their role in spiritual and healing cultures and the production of a federally funded version of Shakespeare’s Macbeth that became known as “Voodoo Macbeth,” featuring an all-black cast performing the Bard’s classic set in Haiti and directed by none other than Orson Welles.

Medical professionals seemed to be either fascinated by the holistic methods of rootwork used to heal both physically and spiritually or appalled at the use of such works. Some professionals claimed to have patients who were undergoing stresses that were attributed to conjure. The 1949 death of a thirty-two-year-old African American female in Montgomery brought attention to cultural stresses and trauma as a possible result of conjure. The woman had discovered a number of strange objects around her home, including various cloths, feathers and colored vials of powder. She feared that someone had crossed her, and she had begun to panic. Over a period of five days, the woman began to grow physically ill. The followi...