![]()

A Modern Sensibility in Older Garb

Henry Wilson’s Rise and Fall of the Slave Power and

the Beginnings of Civil War History

WILLIAM A. BLAIR

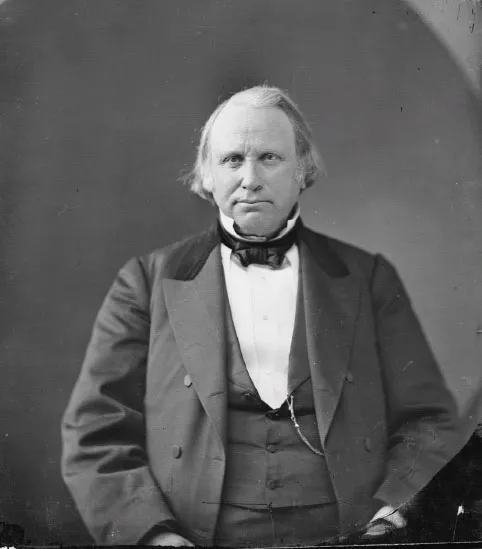

“The Honorable Henry Wilson of Massachusetts.” Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, reproduction number LC-DIG-cwpbh-00671.

Henry Wilson entered politics because he believed that America had a problem. Slavery was not declining as the Founders had hoped, but growing. It threatened to spill beyond state borders into newly acquired territories. To Wilson, this danger existed because southern slaveowners, although a minority of the population, had become a commanding power, especially in the national government where they dominated the presidency, the Supreme Court, and Congress. They sniffed out danger from afar, mobilized agents to act on their behalf, and guarded against anything remotely compromising their interests. They were antidemocratic and brutal. They censored abolition materials in the mails, refused to hear antislavery petitions in Congress, beat to a pulp a leading senator who disagreed with them, browbeat poorer whites of their section into submission, turned the government into abettors of the kidnappers of fugitives, and displayed in general the corruption and violence of men used to wielding the lash. In other words, they trampled on the Constitution, ignoring protections of freedom of speech and the right to petition. It seemed to Wilson as if some “imperious autocrat or secret conclave” conspired to spread slavery everywhere. What was this powerful combination that was centered in the South but had northern allies? Henry Wilson and his Republican colleagues captured this menace in three simple words—the Slave Power.1

Those three little words provided the intellectual basis for three fat volumes of history spanning more than 2,000 pages as Wilson charted how this Slave Power came into being and how it was broken. His monumental The Rise and Fall of the Slave Power in America first appeared in 1872 and took until 1877 to complete. Begun in the late 1860s, it was the work of nearly a decade—work that its author did not live to see completed. Critics generally gave the books a good reception, with most of them noting their chronological sweep from the establishment of slavery through Reconstruction. The set was among the first generation of multivolume histories of the period written by an author recognized as uniquely suited for the task.2 A dedicated abolitionist, he served for more than two decades as a leader of the political antislavery movement, helping to found the Free Soil and Republican Parties, representing Massachusetts in the US Senate, chairing the important Military Affairs Committee during the war, and serving as vice president of the United States in Ulysses S. Grant’s second term. He was a man of principle, dedicated to the antislavery cause out of moral concerns, yet he was, in the words of one biographer, a practical Radical who did not push beyond what he believed was legislatively achievable.3

This nineteenth-century man produced a work that, in its interpretations, is in many ways in synch with the histories written in the twenty-first century. Wilson represented the coming of the war as triggered by a power struggle over whether to contain or spread slavery, not as a battle over some ill-defined or unnamed state rights. Slave masters dragooned the southern states into secession and forced the firing upon Fort Sumter.4 In Wilson’s view, emancipation was the Civil War’s greatest achievement—a conclusion upheld in many historians’ works today. He showed surprising sympathy for Native Americans, characterizing their removal to west of the Mississippi as a plot to advance the land holdings of the Slave Power and their treatment in general as encounters “in which the principles of humanity, honesty, and fair dealing have been so completely ignored and trampled underfoot.”5 He described the Mexican War as a naked conquest to aid the spread of slavery, and Wilson cited a legislator who called it a disgrace to the national character. He tweaked American exceptionalism, arguing that the barbarism in the United States over the slave trade exceeded that of Africa and claiming that the nation practiced a despotism that would strike horror among the monarchists of Europe.6

Wilson also foreshadowed more recent studies of slavery by focusing on its brutality. Though his emphasis on the Slave Power tended to put the focus on the endangerment of white liberties in the North, he still managed to attack the evils of the plantation. Wilson flatly rejected the claim by opponents of abolition that allegations of violence against blacks were exaggerated. He offered a judgment that mirrored the title of a prominent modern book on slavery by saying, “The half was never told.”7 He even unabashedly portrayed the prejudice that existed in the North, including in his own state of Massachusetts, as he catalogued the discriminatory practices throughout much of the Free States that banned black voting, immigration of black people into states, riding with white people on public transportation, and serving on juries. Similarly, he admitted to lukewarm sentiments among many members of his Republican Party when it came to black rights, indicating that they did not all share in antislavery sentiment but dreaded the domination of the Slave Power more, as well as the possibility of a divided Union. “They would accept Abolition rather than disunion,” he observed, “but they did not desire it.”8

Perhaps most surprising was his use of the words “human rights” in a distinctly modern fashion. The language of rights had been coming into its own with the Enlightenment, and the American and French Revolutions. The term “human rights” emerged in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to capture the sense that human beings are born deserving of certain ways of living that cannot be infringed upon or trammeled by an oppressive power. The abolition movement around the Atlantic World provided one of the earlier examples of this new thought. But as modern historians of human rights have asserted, these early manifestations of the term did not necessarily refer to all groups of people, such as Native Americans, black Americans, or women.9

Yet Henry Wilson displayed a modern sensibility in his belief that all individuals were entitled to the same chance to succeed in life and that the way to advance was through Free Labor. More than many of his time, he gathered under the conceptual umbrella of human rights a broader group of people. He was a champion of workers whether white or black, during a time when workers’ rights faced a stiff fight. He believed in an eight-hour workday. He wrote that Native Americans deserved better treatment than they had received from Anglo Americans. After the Civil War, he introduced legislation to eliminate debt peonage in New Mexico territory, another victory in the cause of Free Labor. And although he refused to support women’s suffrage in the Fifteenth Amendment, believing the stand would jeopardize ratification, he did make an unsuccessful attempt at legislation to recognize the right of women to vote in the District of Columbia.10

Henry Wilson’s upbringing reinforced a sympathy with workers and the oppressed. Wilson grew up hard. In fact, he did not start out life as a Wilson at all but as a boy named Jeremiah Jones Colbath. He was born into grinding poverty on February 16, 1812, in the village of Farmington, New Hampshire. His father was a day laborer feeling the economic pinch of the war with England, which had strained commerce throughout the region. Winthrop Colbath does not seem to have been talented as a worker; instead, he excelled at drinking. As eight children came along, food grew scarcer. The boy knew what hunger felt like. “Dreariness and tragedy filled their days,” wrote one biographer.11 The poverty and drinking by the father caused the family to indenture Jeremiah at the age of ten as a servant to a neighboring farmer, a situation that did not end until the young man reached the age of twenty-one.

Overcoming a start that could have held him back in life, he forged himself into a success story. He read voraciously, taking advantage of any opportunity to educate himself. At the age of twenty-one, once free of his indenture, he changed his name, ostensibly a reaction against his father. Why he chose Wilson remains a matter of speculation. Not surprisingly, he pledged himself to life as a teetotaler and supported temperance efforts, connecting him with a social reform movement that also drew many into the cause of antislavery. As a free man he sold the sheep and oxen pledged to him for his indenture and used the proceeds as a grubstake for his start in life. He moved to Natick, Massachusetts, where he learned the shoe trade and, through effort, rose to manage a shoe shop of his own. By 1847, he had grown the business to 109 employees turning out more than 120,000 pairs of shoes per year.12 This background earned him the political nickname of the Natick Cobbler, which highlighted his working-class roots.

Wilson exemplified the Free Labor ideal espoused by Abraham Lincoln and other Republicans for what was supposed to happen in a country that valued work as the way to improve not only oneself but also society. Accumulation of wealth through labor was supposed to result in social mobility. People were to rise from common laborers to shopowners. They were to escape their initial dependency on wages and become independent. The goal, however, was not just to have pecuniary or personal advancement but to ensure that the person could exercise the power of the ballot virtuously and without outside influence. When he reached a level of prosperity that allowed him to give back to society, Wilson chose politics as his instrument. His years as an indentured servant gave him an appreciation for the plight of workers, and it seems natural in retrospect that he dedicated himself to a fight against an entity that was the opposite of Free Labor, the Slave Power.13

One turning point may have come came in 1836 as he journeyed south to Washington to try to recover from unspecified health problems. Wilson reportedly visited slave pens where he saw people manacled, separated, sold, and whipped. He also sat in on Congress and witnessed firsthand how the slaveholding class protected its interests. Overall, the excursion appears to have been a transformative moment. A friend who became a biographer wrote about this time: “His sympathies for the bondmen, his indignation against the cruel system of human traffic carried on hard by the Capitol of a nation boastful of its freedom, were re-awakened, so that he then and there determined, that, come weal or woe, the powers which God had given him should thenceforth be devoted to the destruction of an institution so revolting to every instinct of humanity, so inconsistent with the declaration of our national independence, and so antagonistic to the whole teaching and spirit of the gospel.”14 Whether or not this was the singular episode that turned him into an activist on behalf of abolition, there is little doubt that Wilson made it a life’s mission to destroy slavery.

This goal took him on a journey that began with the Massachusetts legislature and then national office; in the process, he became one of the best-known political figures of his generation. He first ran an unsuccessful campaign in 1839 on a temperance platform and then joined the Whig Party to earn state office. After becoming disenchanted with the Whigs, he helped found the Free Soil Party in 1848 as a means of blocking slavery from the western territories. In the 1850s he led a portion of that organization into the newly forming Republican Party. Later, in the Civil War—as chair of the US Senate’s Military Affairs Committee—he sponsored critical legislation that mustered the resources and the soldiers to win the war. This included the controversial legislation th...