![]()

1 At the Intersection of Language, Learning, and Disability in the Education of Young Bilingual Children

Dina C. Castro and Alfredo J. Artiles

Young bilingual children continue to face the challenge of an education system that is not prepared to meet their needs. For decades, researchers have discussed the disproportionate representation of bilingual children in special education programs (Arreaga-Mayer & Perdomo-Rivera, 1996; Artiles & Ortiz, 2002; Mercer & Richardson, 1975; Rueda & Windmueller, 2006). However, this is an unresolved issue that has negative consequences on bilingual children’s development and learning, especially for those from racial, ethnic and culturally minoritized and marginalized communities. Some progress has been made (Artiles et al., 2010; National Research Council, 2017), but more remains to be done to address and eliminate the persistent barriers to providing equitable and effective services to bilingual children with disabilities. Those barriers include, but are not limited to, early education policies, accountability systems, and programming and instructional approaches that do not support bilingualism and do not consider the role of bilingualism in young children’s development and learning. These are reflected in practices such as the use of culturally and linguistically biased assessment and referral practices and higher education programs that do not prepare professionals to serve bilingual children in general early education settings (Castro, 2014; Zepeda et al., 2011).

Although limited, most research and policies in special education focusing on bilingual children has been conducted with school-age populations. There is a dearth of interdisciplinary research that considers the intersection between the fields of special education, bilingual education, and early childhood education. In this volume we discuss these and other barriers and propose next steps for an integrative and interdisciplinary perspective on early development and education research, policy and practices to address the pervasive challenges and identify opportunities in the education of young bilingual children with disabilities in the United States in the 21st century.

Terms Used in this Book

The term “young bilingual children” is used interchangeably with other terms in this book to refer to children from birth to 8 years of age who grow up exposed to two languages at home, the community and in early care and education programs. Other terms used in the various chapters include those commonly used in the fields of early childhood and elementary education to refer to this population in the United States. Those include “dual language learners,” “English learners,” “English language learners,” and “limited English proficient.” These terms are used because they are associated with specific language policies. The choice of the editors to use “young bilingual children” or “young bilingual learners” is related to how the processes of acquiring and learning in two languages are described in developmental science: the study of bilingualism and bilingual development and its implications for early care and education (National Research Council, 2017).

Related to the scope of the book, the focus is on young bilingual children with disabilities or with a higher probability of having language and communication delays or disorders, as well as cognitive, behavioral, and emotional disabilities. We do not focus on visual, physical, or other health impairments, which deserve an in-depth discussion that is not possible to include in this book.

Chapters in this Volume

In Chapter 2, “A Sociocultural, Integrative, and Interdisciplinary Perspective on the Development and Education of Young Bilingual Children with Disabilities,” Dina C. Castro, Cristina Gillanders, Nydia Prishker, and Rodolfo Rodriguez present conceptual premises and empirical evidence in support of a sociocultural and integrative perspective when serving young bilingual children from birth to 8 years of age in early care and education, early intervention (EI) and special education programs. They argue that the unique experiences of young bilingual children at home, in their communities, and in society at large contribute to defining these children’s development in a distinct way. Furthermore, the authors argue that the education of young bilinguals in the United States should move beyond an exclusive focus on English language acquisition to designing practices that take into consideration how children’s bilingualism influences all developmental domains and learning processes. They discuss the need for shifting paradigms from a deficit to a strength-based approach in research, policy and early education practices with young bilingual children.

Chapter 3, “How Bilingualism Affects Children’s Language Development,” by Carol Scheffner Hammer and Maria Cristina Limlingan, focuses on developmental science related to bilingualism. Traditional approaches to developmental research have tended to view bilinguals as two monolinguals in one. This, in turn, has led to research in which the developmental outcomes of these children have been interpreted with reference to the performance of monolinguals. A major shortcoming of this approach is that it fails to take into account the extent to which the bilingual experience determines a particular developmental pathway for these children. This chapter discusses how bilingualism affects language development of children with disabilities. An understanding of the developmental characteristics of emergent bilinguals is essential for designing effective early intervention and educational approaches for these children.

Chapter 4, “Dual Language Learners in Early Intervention Programs: Issues of Eligibility, Access, and Service Provision,” by Lillian Durán, focuses on bilingual children from birth to 3 years of age, discussing issues related to how young bilingual children are identified for services, including challenges faced by their families to find and access services. This chapter also discusses the availability of qualified early intervention providers and implementation of culturally and linguistically responsive early intervention services for very young children growing up bilingually.

Chapter 5, “Dual Language Learners with Disabilities in Inclusive Early Elementary School Classrooms,” by Sarah L. Alvarado, Sarah M. Salinas, and Alfredo J. Artiles, centers on approaches to providing instruction to young bilingual children with disabilities in inclusive settings. Various current approaches are described, and their appropriateness and effectiveness are discussed. A related issue discussed is the opportunities provided in inclusive classrooms for young bilingual children with disabilities to become bilingual. Still today, there are professionals who conduct interventions only in the majority language (English) and base their recommendations on the outcomes of this focus. In this environment, parents give up on being able to communicate with their children fluently in their family’s primary language, thus limiting opportunities for children to experience rich language environments.

Chapter 6, “Language Learning and Language Disability: Equity Issues in the Assessment of Young Bilingual Learners,” by Maria Adelaida Restrepo and Anny P. Castilla-Earls, covers how the need to differentiate language learning from language disability is still a challenge for early interventionists and special educators. The limited availability of valid and reliable assessment instruments for bilingual children and assessment policies and procedures that do not take into account their bilingual development characteristics results in inaccurate identification, or no identification, of these children for early intervention and special education services. These challenges apply also to assessments conducted for progress monitoring and intervention planning purposes. This chapter presents an overview of these issues and outlines emerging findings that promise to advance this area of inquiry.

Chapter 7, “Learning from Sociocultural Contexts: Partnering with Families of Young Bilingual Children with Disabilities,” by Cristina Gillanders and Sylvia Y. Sánchez, centers on the development of bilingual children and how development cannot be understood without considering the kinds of routine activities in which they engage within their family contexts. The demographic characteristics of the families of children growing up bilingually are frequently used as a proxy for the limitations that these families may experience in being able to provide support for their children’s development. However, relying on demographic characteristics such as socioeconomic status or parental education can prevent researchers and educators from identifying family processes and routines that may constitute positive or protective factors to promote their children’s development and learning. This chapter discusses these issues and their implications for building partnerships with families of young bilingual children with disabilities.

The implementation of early education practices that address the characteristics and needs of bilingual children with disabilities depends mostly on the preparation of their educators.

Chapter 8, “Preparing Teachers of Young Bilingual Children with Disabilities,” by Norma A. López-Reyna, Cindy L. Collado, Mary Bay, and Wu-Ying Hsieh, discusses the knowledge, skills, and dispositions that should be the focus of teacher preparation and professional development intended to improve the quality of early intervention and special education services for young bilingual children with disabilities. This is particularly relevant in the context of inclusive classrooms serving these children. Also, the importance of increasing the cultural and linguistic diversity of the early childhood special education workforce is discussed.

In Chapter 9, “Language, Learning, and Disability in an Era of Accountability,” Marlene Zepeda and Michael J. Orosco discuss the definition and assessment of program and classroom quality in the early grades (PreK-3) in the context of the current Quality Rating Improvement Systems that most states are currently implementing, as well as federal policies such as No Child Left Behind and the Common Core State Standards. Also, kindergarten entry assessments are discussed, focusing on the extent to which these and other accountability initiatives include indicators to assess educational practices that meet the needs of dual language learners with disabilities. Relevant to this discussion is how prepared early childhood programs, schools, and teachers are to serve their increasingly diverse child populations in early intervention and special education.

In Chapter 10, “Young Bilingual Children with Disabilities: Challenges and Opportunities for Future Education Policies and Research,” Alba A. Ortiz discusses the main themes covered in this volume and outlines challenges and opportunities for federal legislation, identifies gaps, and presents recommendations for future research on this critical topic.

The discussions in the chapters of this volume provide readers with up-to-date information and critical perspectives with the purpose of bringing the early education of young bilingual children to the forefront of the debates at the intersection of early childhood education, special education, and bilingual education. Given the current state of knowledge, there is no justification for the persistence of policies and practices that negate young bilingual children with and without disabilities access to early intervention and early education that allows them to reach their full potential.

References

Arreaga-Mayer, C. and Perdomo-Rivera, C. (1996) Eco-behavioral analysis of instruction for at-risk language minority students. Elementary School Journal 96, 245–258.

Artiles, A.J. and Ortiz, A.A. (eds) (2002) English Language Learners with Special Education Needs. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics.

Artiles, A.J., Kozleski, E.B., Trent, S.C., Osher, D. and Ortiz, A. (2010) Justifying and explaining disproportionality, 1968–2008: A critique of underlying views of culture. Exceptional Children 76, 279–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440291007600303.

Castro, D.C. (2014) The development and early care and education of dual language learners: Establishing the state of knowledge. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 29, 693–698.

Mercer, J.R. and Richardson, J.G. (1975) Mental retardation as a social problem. In N. Hobbs (ed.) Issues in the Classification of Children (vol. 2, pp. 463–496). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

National Research Council (2017) Fostering School Success for English Learners: Toward New Directions in Policy, Practice, and Research. Washington, DC: National Research Council.

Rueda, R. and Windmueller, M.P. (2006) English language learners, LD and overrepresentation. Journal of Learning Disabilities 39, 99–107.

Zepeda, M., Castro, D.C. and Cronin, S. (2011) Preparing teachers to work with young English language learners. Child Development Perspectives 5 (1), 10–14.

![]()

2 A Sociocultural, Integrative, and Interdisciplinary Perspective on the Development and Education of Young Bilingual Children with Disabilities

Dina C. Castro, Cristina Gillanders, Nydia Prishker, and Rodolfo Rodriguez

Language diversity has been a characteristic of societies around the world for millennia (Franceschini, 2013). Colonization and migration movements have contributed to the linguistic and cultural diversity in many communities. During the 21st century, the number of people leaving their communities in search of a better life for themselves and their families has increased dramatically. In 2015, 47 million or 19% of the world’s total international migrants lived in the United States (United Nations, 2016). Bilingualism in the early years (birth to age 8) is found largely among children in immigrant families, the majority of whom are US citizens (Park et al., 2018). However, there are also bilinguals among children of US born heritage language speakers (second generation and above) and children in indigenous families (Migge & Léglise, 2007). Bilingual children are a third (32%) of the US child population ages 0–8 and constitute a higher percentage in some states: 60% in California and 49% in Texas and New Mexico (Park et al., 2017a, 2017b, 2017c, 2017d). Regarding bilingual children with dis/abilities, in 2013, 339,000 infants and toddlers (ages birth to 2 years), more than 745,000 children ages 3–5, and 5.8 million children and youth ages 6–21 were served under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) of 2004 (US Department of Education, 2015). The percentage of bilingual children enrolled in English language instruction educational programs (K-12) identified as having a dis/ability varies across states. Data available for the 2013-2014 school year show a national average of 12.8%, with percentages as high as 21% in New York, and 18% in Illinois, while some states have lower than the average percentages, such as Maryland with 5.6% and Texas with 7.6% (US Department of Education, 2020).

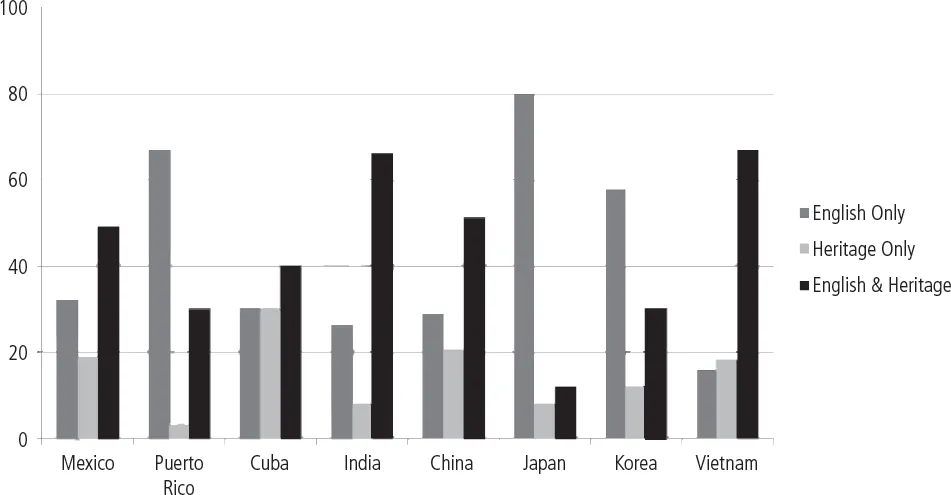

There is great variability in the languages spoken in the United States. In 2016, the US Census Bureau reported that more than 350 languages were spoken in the country by people 5 years of age and older. Among those speaking languages other than English, the five most spoken languages or groups of languages include Spanish (62%; with speakers from more than 20 countries), Chinese languages (4.7%; includes Mandarin, Cantonese and others), Native American languages (4.3%), Tagalog (2.7%), and Vietnamese (2.3%). The use of each of their two languages among bilingual families varies. For instance, a study conducted by Winsler and colleagues (2014) analyzed preferences in the use of home language and English in a national representative sample of immigrant families by country of origin and found that among Asian families, a larger percentage of Vietnamese families were bilingual (used both their home language and English) (66%) than Japanese families, the majority of whom used English only (80%). Among Latino families, more Mexican families tend to be bilingual (49%) than Puerto Rican (30%) and Cuban families (40%), with Puerto Rican families (living in the US mainland) using English only more (67%) than Mexican (32%) and Cuban (30%) families. Figure 2.1 shows the percentages of language(s) used (English and another language, English only, and only another language) by immigrant families from eight countries.

Figure 2.1 Language use among families of bilingual children in the United States by country of origin (Winsler et al., 2014)

In addition to this linguistic diversity, bilingual children are from diverse racial, ethnic, and cultural communities. In spite of this diversity, many research studies on child development and learning of bilingual children still use predominantly an English monolingual Eurocentric middle-class perspective. This means that bilingual children and families’ characteristics are often compared to those of monolinguals. This deficit view ignores the complexities inherent to being bilingual and the richness of these children’s experiences in the context of their families, communities, and early care and education settings. This deficit-oriented research then informs the development of early learning policies and curriculum approaches and programming in early childhood care and education, establishing “norms” and developmental expectations based on the mainstream/dominant culture’s beliefs and practices (Pérez & Saavedra, 2017).

As a consequence, bilingual children from diverse racial, ethnic, and cultural communities, whose development and learning may not always conform with the established norm, may be seen as deficient. A demonstration of this perspective are accountability systems that currently govern early education, such as Kindergarten Entry Ass...