![]()

PART ONE

Resistance by Wiles

![]()

1. Day-to-Day Resistance

I rather be beat to death than worked to death.

—Octavia Stephens to Winston Stephens, March 2, 1862

The majority of Florida’s enslaved blacks of the nineteenth century lived and worked in “slave labor camps,” as Peter Wood articulated the situation; most did so as nonviolent dissenters, even though many men, women, and even children physically resisted slavery and its cruelties. This resistance occurred despite the fact that bondservants understood the dire, self-destructive, and even deadly consequences of outright rebellion or retaliation. As early as 1828—only seven years after the United States had assumed control over the former Spanish colony—this reality had hardened into law. That year, Florida’s criminal code was amended to create latitude for the exercise of cruelty by slave owners through the stipulation that “Slaves, Free Negroes, and Mulattoes” could suffer whippings and even death depending upon the severity of the infraction committed. Historian James M. Denham correctly noted that “with some minor revisions, the code remained in force throughout the entire antebellum period, and all blacks—bond or free—were subject to its proscriptions.”1

In the circumstances, the enslaved usually and creatively opted to utilize a wide variety of options when it came to forms of dissent. Most commonly, their actions understandably were based on a conservative approach. That typical nonviolent approach being the case, it should be emphasized that numerous individuals refused to hide behind deferential facades when addressing their discontentment or dissatisfaction with their lot; they simply spoke their minds. Others stole food, hogs, cattle, sheep, poultry, money, liquor, cotton, indigo, corn, and just about anything else they could get their hands on. Added to those ranks were slaves who revealed their irritation with what they had to wear by making or acquiring additional clothing. Others simply worked slowly or carelessly. Some bondservants quietly resisted by learning to read and write. They might also have destroyed wagons, carriages, or equipment or mistreated livestock. Most at some time feigned illness for brief reprieves from work routines. Bondpeople, as Kenneth M. Stampp aptly noted, became a daily “troublesome property” for their owners.2 This clearly was the case in Florida.

Appropriately, then, this chapter explores the various forms of conservative resistance used by slaves in Florida and often elsewhere within the slave empire of the United States. William Dusinberre called these types of actions or inactions nonviolent “dissidence.” Indeed, bondservants actively, though discreetly, resisted their owners on a day-to-day basis. In doing so, many slaves believed that they could either get away with their recalcitrance or use it to negotiate concessions from their masters. Since enslaved blacks knew that violent attack could mean immediate death, they naturally and intelligently sought other means of expressing their discontent concerning plantation or farm regimens. Sometimes they made life uncomfortable for their masters, and sometimes, in the process, they made life uncomfortable for themselves.3

Scholars of the subject have reviewed newspaper accounts, plantation journals, diaries, ledgers, letters, and personal notes of slaveholders to determine what whites thought of the reasons for the rebellious nature of their bondservants. As Gerald W. Mullin, John W. Blassingame, Merton Dillon, Douglas R. Egerton, and others have suggested, however, another way to understand the objectives of individuals who resisted bondage would be to focus on the slaves themselves. For studying nineteenth-century slave resistance, slave narratives and testimonies—as well as the writings of bondservants—can be useful in understanding how enslaved blacks reacted to their bondage. Failure to appreciate what such sources have to offer can easily lure the historian to misleading insights and misdirected conclusions.4

With an important exception that will be considered in due course—that of the Second Seminole War (or the Florida Black/Indian Rebellion) era of 1835–42—few of Florida’s slave owners overtly expressed concern about possible massive violent uprising by their bondservants. Yet, they sought and enacted various laws suggesting otherwise. By virtually copying the laws of the older slave states, Florida’s slave owners presumably sought to shore up their control over their property. Day-to-day reality popped such bubbles of optimism. Many slaveholders knew that placing laws on the books to control the bondservant was one thing, while enforcing those laws in a consistent manner over a sustained period of time clearly represented a distinctly separate matter. The laws framed to control slaves, as it turned out, did not apply neatly to managing the realities of life on farms and plantations.5

Daily Existence

Although masters appreciated that the enslaved could commit sudden and sometimes unprovoked acts of violence toward members of the slaveholding class, the bigger problem they recognized involved the day-to-day dissidence of “their people.” Indeed, this dissident army, as John Hope Franklin and Loren Schweninger fittingly called them, left an indelible impression on the minds of many Florida masters. An apostate host, it consisted of slaves who had become acculturated or assimilated into Florida’s slave society. Which is to say, the dissident army included nearly all of Florida’s slaves.6

And the numbers of Florida’s rebels and runaways grew with an ever-increasing slave population. A few statistics can help to make the point. Although less populous than most of its southern counterparts, Florida grew steadily after 1821. Its numbers of persons held in bondage, meanwhile, expanded at a much faster rate than in most other southern slave states from 1830 to 1860 (the exception was Arkansas). Census takers reported the facts: Florida’s enslaved population increased by an astonishing 298.2 percent between 1830 and the Civil War’s beginning, from 15,501 persons to 61,745.

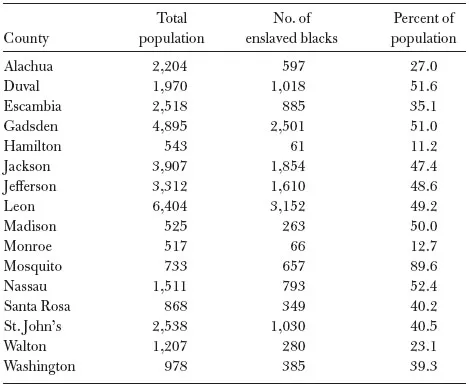

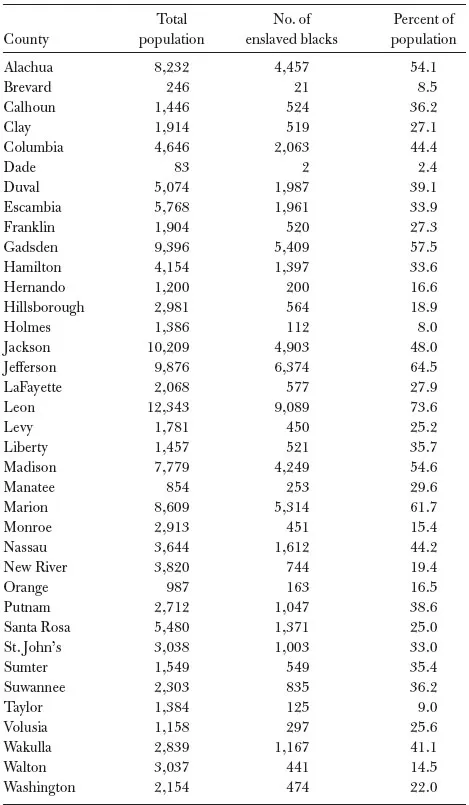

As tables 1 and 2 illustrate, Florida counties increased from sixteen in 1830 to thirty-seven in 1860, all holding enslaved workers. In 1830, the population of bondservants in ten counties (or 62 percent) ran 40 percent or higher. Thirty years later, with twenty-one more counties, still only ten (27 percent) claimed enslaved populations of at least 40 percent. Here the state’s slave belt centered.

Table 1. Florida Population by County, Number of Enslaved Blacks, and Their Percentage in Each County in 1830

Source: United States Census Office, Population of Each State and Territory (by counties) in the Aggregate and as Whites, Free Colored, Slave, Chinese, and Indian, at All Censuses, 1790 to 1870 (Washington, D.C: Government Printing Office, 1872), 18–19.

Table 2. Florida Population by County, Number of Enslaved Blacks, and Their Percentage in Each County in 1860

Source: United States Census Office, Population of Each State and Territory (by counties) in the Aggregate and as Whites, Free Colored, Slave, Chinese, and Indian, at All Censuses, 1790 to 1870 (Washington, D.C: Government Printing Office, 1872), 18–19.

It bears mention that, by 1830, over 98 percent of Florida slaves had been acculturated into Anglo-American society, at least in terms of being Americanborn and adopting, if only partially, the Christian religion of their masters. As will be seen later, the Middle Florida region, stretching through the panhandle from Jackson County on the west to the Suwannee River on the east, consisted of six counties where over half of all enslaved blacks lived and worked by 1860. There, they engaged in Protestant worship, typically as Methodists, Baptists, Presbyterians, or Congregationalists. In West Florida—principally the Pensacola vicinity and adjacent areas—and East Florida, including the northeast and the peninsula, centuries of Spanish influence persisted in various degrees in various places. So, at locales such as Pensacola, St. Augustine, and other locations, worship might include Roman Catholicism. Baptist and Methodist itinerant preachers began to appear in East and West Florida only in the 1820s and 1830s after Spain’s cession of the colony to the United States in 1821. The few slaveholders and bondpeople who lived in the central and southern regions of the peninsula may have identified with any of the aforementioned religions, or they may not have claimed Christian religious faith at all.7

In addition to influences surrounding acculturation, attitudes and actions of individual masters also must be considered in any discussion of how blacks reacted to their enslavement. A master, for example, could opt—and many did—for a paternalistic approach based upon persuasion, incentives, or a simple give-and-take. But, because of the refusal of some bondservants to be driven beyond a certain point in their work routines, the master’s persuasive manner might well not alter work performances.

The experience of a woman named Holly helps to make the point. According to her sister Margrett Nickerson, Holly refused to be pushed at any rate of speed other than the one she established for herself. Nickerson recalled, “Holly didn’t stand back on non’ uv em, when dey’d get behin’ her, she git behin’ dem; she wuz dat stubbo’n and when dey would beat her she wouldn’t holler and jest take it and go on [at her own pace].” Margrett meanwhile also resisted working other than at her own pace. She remembered that, when she had to “tote tater vines on my haid,” overseer Joe Sanders would hurry her and other slaves, “beatin’ us with strops and sticks.” She told of an incident when the overseer beat her and another slave for working slowly, leaving Margrett crippled. Her injuries proved permanent, even though her father “would try to fix me up cose I had to go back to work nex’ day.” She added, “I never walked straight from [that] day to now.”8

Sometimes, tenacious behavior by the enslaved, while raising the ire of slaveholders, surprisingly sparked little or no further response. Emmaline’s example illustrates the point. She, like many other enslaved blacks, was a commodity supplied by the international slave trade, or “Black Mother.” But, the migration of bondpeople not only encompassed travel from various parts of Africa to North America. The journey for many, much like that of Emmaline, began or continued with bondservants and their families being uprooted from the Upper South (Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas) to the Lower South for the purpose of making owners wealthy. In Emmaline’s case, as a Maryland-born bondservant, she had been uprooted and forced to migrate to the fertile, but also violent, Florida frontier. The dynamic of relocation that touched Emmaline, as several students of the subject have noted, emerged during the Great Migration of the 1820s and 1830s, one of the largest, if not the largest, forced removal of enslaved blacks in US history. On a personal level, Emmaline’s experience united her with several thousand black migrants compelled to accompany planter families from Upper South states to Florida.9

In Emmaline’s case, the family that mandated her move was that of prominent Maryland planter and politician William Wirt, who relocated her and twenty other slaves to the new town of Tallahassee in 1828. If her journey reflected that of other captive laborers who traveled with their planter owners from the Upper South to Florida, the trek would have unfolded as arduous at best. This was seen in the case of northern Virginia’s Thomas Brown, who, with his family and 140 slaves, also came to Leon County. In 1827, Brown reflected on this particular trip by observing that white men rode on horses and the white women rode in wagons. Most adult bondservants and children walked the two-month journey on foot at fifteen to twenty miles per day. Once the caravan stopped for the evening, the bondpeople had to cook and provide musical entertainment for the whites. They passed the night in “‘open tents [on] one long strip of cloth,’ while whites slept in tents with walls and doors.” Thus, having likely walked the two- or three-month trip from Maryland to Tallahassee, Emmaline and her fellow Wirt slaves surely were exhausted. Nonetheless, Laura Wirt Randall, whose husband, Thomas, had charge of her father William’s plantation, voiced complaints shortly after their arrival that Emmaline was working too slowly.10

That proved only the beginning of Emmaline’s Florida experience with dissidence. On another occasion, Randall noted that Emmaline did not want to wash clothes. “She is very slow and loitering,” the owner insisted. Another day, Laura complained that Emmaline had taken a whole day scouring one side of the porch. After seven months, Emmaline had not changed her behavior to Randall’s liking. In frustration, Laura told her father that the bondservant had become too “impudent and unmanageable.” Emmaline could have been protesting her uprooting and separation from family and friends in Maryland, but, the reason notwithstanding, she successfully resisted owner demands. Not insignificantly, as an acculturated house servant with religious underpinnings, Emmaline, along with other uprooted Maryland slaves, did work feverishly to build a small church of their own within three months of their arrival.11

The slaveholder, of course, might choose to be an absentee owner, in which case overseers typically undertook to regulate bondservant life and duties. Some of these individuals tried to pattern their behavior after the paternalistic gestures of the employer, as was the case with Judge Roberson. He sought to use kindness instead of more direct persuasive actions. The enslaved, unfortunately for Roberson and his employer George Noble Jones, perceived their supervisor to be weak and took advantage of him. Jones’s bondservants on his several Middle Florida plantations clearly understood that their master lived primarily on his larger Savannah estate and came to look after his interests in Middle Florida only periodically. With the knowledge, they played games of deception with the overseers. Some even would pretend to be at the worksite when actually sleeping in their cabins.

D. N. Moxley, overseer on another Jones plantation, recognized what was happening under Roberson’s watch and came to look upon his peer as an inept manager. He related his opinion to fellow overseer John Evans, who in turn wrote the owner. “Mr. Moxley sees that he had to flog one of the Judge hands out of the Quarters for sleeping all morning until an hour or two after sun before he left for the mill,” the letter read. “Ansler is the boy’s name. Mr. Moxley ses that the Judge has not bin on the canal in nearly two weeks where the hands are at work. If this be the case they aint hurting themselves at work very much.” The bondservants had come to expect a certain management style from Roberson, since he oftentimes did not spot-check their work, and they acted in their own interest accordingly. Notably, although Roberson allowed the bondpeople much more latitude than did either Moxley or Evans, Jones declined to replace him.12

Bondservants would have known that their behavior of laboring at a slow pace could be self-destructive—after all, they faced potential flogging for poor work performance; still, they oftentimes did not modify that behavior until concessions were made. Take the case of Die, for instance. The bondwoman was another of George Noble Jones’s slaves who had been whipped by the overseer for working slowly and for otherwise not performing her duties. Yet, she had persisted in her refusal. Frustrated with her actions, the overseer sent the recalcitrant woman to another Jones plantation, where the attitudes of the bondservant slowly began to change. As a result, Die’s new overseer then asked that she be left under his supervision, since she had no problems working for him. He went on to observe, “I have not had a cause to strike her a lick.” Sometimes being disagreeable earned the enslaved a measure of satisfaction, even if for a short period of time.13

The numbers again can offer a bit of insight. Out of over 1,403 pertinent references from Florida probate records, slaveholders’ journals, diaries, ledgers, and letters from 1821 to 1865, a total of 267 bondservants were cited at least one time as being lazy or as performing work routines poorly. Focusing specifically on gender, men made up 48 percent; women, 52 percent. Most of the references came from the 1850s. In fact, prices of staple crops began slowly to increase during that decade, after a scandal known as the Union Bank debacle had undermined a Flori...