![]()

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Hope for the Future of the Postindustrial City

DONALD K. CARTER

Well I went back to Ohio | But my city was gone | There was no train station | There was no downtown

“My City Was Gone” (1982)—The Pretenders (music and lyrics by Chrissie Hynde)

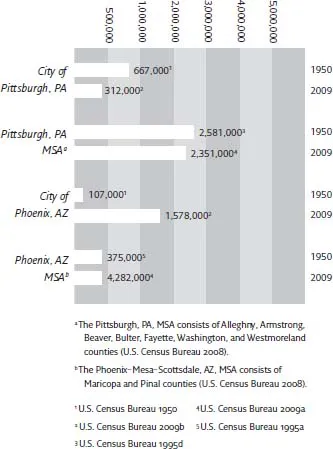

The term “postindustrial” was first popularized by Daniel Bell in his 1973 book The Coming of Post-industrial Society, in which he forecast that mature national economies were moving and would continue to move from being manufacturing based to service based. The United States indeed went in that direction and prospered overall. What Bell did not predict were the severe regional disparities that would result between the so-called Rust Belt cities of the Northeast and Midwest and the Sun Belt cities of the South and Southwest. Over the next 40 years, Rust Belt cities were characterized by depopulation, disinvestment, and decline while Sun Belt cities were characterized by population explosion, economic growth, and sprawl. Graph 1.1 illustrates the magnitude of this geographic shift, comparing population change in two representative cities, Pittsburgh (Rust Belt) and Phoenix (Sun Belt), and their respective Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAS) between 1950 and 2009. The symptoms of decline in the Rust Belt are well known, the causes have been identified, and the diagnosis has been consistently grim for cities like Detroit and Youngstown, Ohio.

This chapter will present a more optimistic future for the postindustrial cities of the Rust Belt. The transformation of the “Steel City” of Pittsburgh into a technology and financial center will be featured as a case study. Although “Shrinking Cities” — a term some consider pejorative — have indeed bled jobs and people for decades in the Northeast and Midwest, the cities themselves remain national treasures not to be tossed aside like the silver ghost towns of Nevada. Shrinking cites with well-planned postindustrial redevelopments, such as SynergiCity, have the best attributes of “Smart Growth,” including walkable neighborhoods, affordable housing, historic downtowns and main streets, strong universities and hospitals, cultural amenities, parks, unused infrastructure capacity, development density sufficient to support public transit, and abundant water.

By contrast, the burgeoning cities of the Sun Belt are low-density, auto-dependent, and surviving on ever-diminishing supplies of borrowed water. Sun Belt economies have been driven not by diverse economies but by the business of growth itself, such as home building and construction, which the Great Recession of 2008-2009 revealed as illusory and unsustainable (Florida 2010). A new terminology now seems appropriate. Rust Belt becomes “Water Belt.” Sun Belt becomes “Drought Belt.”

We cannot undo the post-1950 global economic patterns that led to these regional inequities, but we can provide strategies for the rebirth of our industrial heartland in the postindustrial economy, especially if redevelopment is tackled on a regional basis, not just in the central cities. The regional cities of the Water Belt may now, half a century later, have regained a competitive advantage. They have space to grow internally on vacant and underutilized land. They have adaptable buildings and walkable neighborhoods. They have roads and utilities in place. They have strong institutional resources. They are places of authenticity and heritage. They have the persistence, strength, and resiliency of the people who did not leave. They have water.

GRAPH 1.1. Populations of Pittsburgh (Rust Belt) v. Phoenix (Sun Belt) in 1950 and 2009. (Courtesy of Donald Carter)

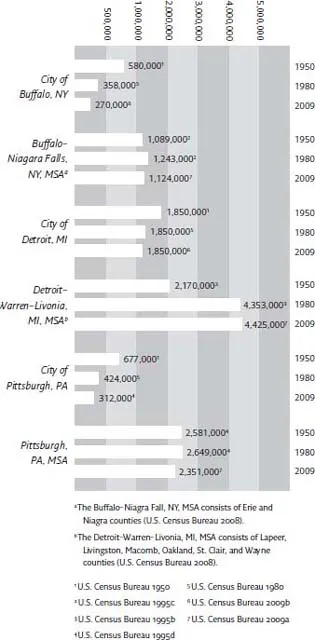

GRAPH 1.2. Population Change in Buffalo, Detroit, and Pittsburgh, 1950-2009. (Courtesy of Donald Carter)

There is every reason to believe that many of these American heartland cities can, with proper planning and investment, repopulate and prosper as some of the expanding U.S. population (300 million people in 2010 to 400 million in 2050) migrates to sustainable and livable cities with high quality of life, affordability, amenities, and economic opportunity. This can be the future of American postindustrial cities and can be a replicable model for postindustrial cities internationally.

Pathology of Postindustrial Cities

Well we’re living here in Allentown

And they’re closing all the factories down

Out in Bethlehem they’re killing time

Filling out forms, standing in line

“Allentown” (1982) (music and lyrics by Billy Joel)

There is an established pathology for American postindustrial cities. The symptoms are well known and follow a well-documented pattern: loss of industrial jobs; subsequent loss of support and multiplier jobs; out-migration and population loss; lack of private investment; tax base decline; neglect and disinvestment in infrastructure and public services; abandoned factories; brownfields; vacant houses; vacant land; declining real estate values; loss of family equity; increased poverty; and finally, loss of hope and psychological depression.

The United States is not alone in experiencing postindustrial decline. In 1988, the International Remaking Cities Conference was held in Pittsburgh with over 350 delegates from industrial regions such as the Ruhr Valley in Germany, the Midlands in England, and the Monongahela Valley in Pittsburgh. Urban designers, market economists, architects, and citizens shared ideas for the reinvigoration of postindustrial cities that informed subsequent redevelopment policy in the Pittsburgh region (Davis 1989).

Graph 1.2 tracks population for three representative postindustrial U.S. cities and their respective MSAS from 1950 to 2008: Buffalo, Pittsburgh, and Detroit. Note that the central cities suffered large declines in population compared to their regions, which experienced moderate growth or decline. This reflects the 65-year pattern of suburbanization of America that accompanied the emptying out of the urban core, a national trend termed by Rolf Pendall (2003) as “sprawl without growth.”

The causes of the decline of postindustrial cities in the Northeast and Midwest are likewise well known: loss of basic industries to low-cost, nonunion producers in the Sun Belt, Far East, and Mexico; an entrepreneurial vacuum creating no new industries to replace the lost jobs; the lure of suburbia; racial conflict; white flight; middle-class flight; concentration of poverty and crime in the urban core; investment in highways over public transit; steady decline of funding for essential services such as schools, parks, and public works; and the overall deterioration of the built environment, including streets, bridges, and buildings. Why stay?

The standard prognosis for postindustrial cities has been bleak. At worst, these cities are dead and will not come back. At best, they will become Shrinking Cities populated by an increasingly aged and poor population. They will have to do less with less. Like Camden, New Jersey, they will become “wards of the State” (Gillette 2005: 39). Whole parts of cities will be abandoned. Indeed, some of this is happening already in Detroit, Buffalo, and Flint, Michigan, where “managed decline” is the new strategy (Oswalt 2006a; Pallagst et al. 2009) and once-vibrant neighborhoods are being transformed into urban farms, recreational amenities, green infrastructure zones, and natural areas. Such downsizing strategies have been successfully adopted in depopulated cities in the former East Germany in an attempt to match cities’ footprints to their new populations (Müller 2010). This still may be the fate of some cities. But there is an alternative scenario, best exemplified by the remaking of Pittsburgh, the quintessential industrial city and personification of the Rust Belt.

What Happened in Pittsburgh

Now Main Street’s whitewashed windows and vacant stores

Seems like there ain’t nobody wants to come down here no more

They’re closing down the textile mill across the railroad tracks

Foreman says these jobs are going boys and they ain’t coming back to

Your hometown, your hometown, your hometown, your hometown

“My Hometown” (Music and lyrics by Bruce Springsteen, 1984)

The song lyrics quoted about the breakdown of the Midwest’s great industrial cities by Chrissie Hynde, Billy Joel, and Bruce Springsteen are from the 1980s. That is not a coincidence; it was indeed a dire time. Pittsburgh and many of its sister cities across the Northeast and Midwest lost their industrial bases in the space of a few years and went into precipitous, seemingly irreversible decline. That has not been the outcome for Pittsburgh. There are lessons to be learned in recounting how Pittsburgh was transformed in one generation from “Steel City” to “Knowledge City” (Carnegie Mellon University 2002) and how it became “a center for technology and green jobs, health care and education” (Obama 2010). The remaking of Pittsburgh did not happen by chance or luck. It was the result of a realistic assessment of assets and problems, imaginative long-range economic regional planning, a shared vision, a tradition of successful public-private partnerships, involvement of concerned private organizations, authentic citizen participation, strategic investments, organized feedback and evaluation, and patience to stay the course. First, a brief history of industrial Pittsburgh is in order to understand the city’s underlying “DNA.” Its current vibrancy is built on the legacy of three successive eras: Industrial Powerhouse (1865-1945); Renaissance (1945-1985); and Regrouping and Transformation (1985-present).

FIGURE 1.1. Downtown Pittsburgh (daytime), c. 1940. Street lights were turned on during the day. Businessmen put on clean shirts in the afternoon. (Photographer unknown. Image courtesy of Smoke Control Lantern Slide Collection, Archives Services Center, University of Pittsburgh)

INDUSTRIAL POWERHOUSE (1865-1945)

The unprecedented industrial growth of Pittsburgh between the Civil War and World War I was the foundation for all that followed. That expansive era was made possible by nearby natural resources, particularly coal, oil, and gas; good transportation connections via rivers, canals, and railroads; an abundance of immigrant workers; and the genius and resourcefulness of a remarkable group of entrepreneurs: Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick, H. J. Heinz, Andrew Mellon, and George Westinghouse, to name the most famous.

Pittsburgh was truly a boomtown, albeit a polluted one, indelibly characterized by James Parton in 1868 as “Hell with the lid taken off” (Cronin 2008). In the 1870s, Pittsburgh was called the “‘Forge of the Universe,’ turning out half the glass, half the iron, and much of the oil produced in the United States” (Toker 2009). Between World War I and World War II, Pittsburgh maintained its place as one of the largest industrial centers in the world, despite suffering an economic downturn during the Great Depression of the 1930s. The armaments needed for World War II brought the city back to full employment as new factories were built overnight and pollution poured from the smokestacks and into the rivers. Streetlights were on at midday. Pollution meant prosperity (fig. 1.1).

RENAISSANCE (1945-1985)

In 1943, as World War II raged, Pittsburgh civic and business leaders, led by Democrat mayor David L. Lawrence and Republican business magnate Richard K. Mellon, son of the famed banker Andrew Mellon, determined that cleaning up the image of the city was critically important. This era has been dubbed “Renaissance I”; it included a smoke control ordinance, locks and dams on the rivers to prevent flooding, four major urban redevelopment projects (Gateway Center, Lower Hill, North Side, and East Liberty), and an urban highway system. Corporate headquarters were built for U.S. Steel, Alcoa, Mellon Bank, and Westinghouse. A new key player on the private side, the Allegheny Conference on Community Development, was formed in 1945 and was comprised of the CEOs of Pittsburgh’s corporations, banks, private foundations, and universities.

“Renaissance II” is associated with Mayor Richard Caliguiri (1977-1988). During his time in office, a $2 billion downtown development boom occurred with six new office towers and a convention center hotel (fig. 1.2). The construction of a light rail subway system downtown and an exclusive busway to the eastern part of the city further strengthened the employment function of the urban core. Caliguiri also developed strategies for neighborhood revitalization, including housing rehabilitation and new infill development. Midway through his term of office, the steel industry in the Pittsburgh region collapsed, and 133,000 manufacturing jobs were lost in the span of eight years (Bureau of Economic Analysis 2010).

REGROUPING AND TRANSFORMATION (1985-2010)

Not only did the Pittsburgh region lose basic manufacturing jobs, but in 1985, Gulf Oil, a Fortune 500 company founded and headquartered in Pittsburgh, ceased to exist as it merged with Chevron, moving all operations to Houston and San Francisco. Rockwell International and Koppers likewise disappeared in mergers and acquisitions. Westinghouse faced financial problems that led to its eventual breakup into separate companies and subsequent loss of jobs in Pittsburgh. Things looked bleak. Families left the region for points south and west in quest of jobs. “Rust Belt” started to sound about right.

FIGURE 1.2. View of Downtown Pittsburgh, “The Golden Triangle,” 2008. The Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers meet to form the Ohio River. Over 300,000 persons work downtown. (Courtesy of Bobak Ha’Eri)

Improbably, in the midst of these losses, Rand McNally’s Places Rated Almanac crowned Pittsburgh the nation’s “Most Livable City” in 1985, displacing Atlanta, to its disbelief and dismay, and producing derisive snickers coast to coast. That surprising designation offers an important key to the continued resilience of Pittsburgh: quality of life. The city received medium and high marks for climate and terrain, housing, health care, transportation, education, the arts, recreation, and economic outlook. In essence, the Most Livable City designation was and is a measure of quality of life, and Pittsburgh was exceptional. Pittsburgh was named Most Livable City by the Places Rated Almanac again in 2007. In 2009, the British magazine Economist rated Pittsburgh the Most Livable U.S. City and twenty-ninth in the world. A year later, Forbes named metropolitan Pittsburgh the Most Livable City in the country and the Best Place to Buy a Home (Kalson 2010). Other recent accolades for the Pittsburgh region include “Number 1 Commercial Real Estate Market” in 2009, from Moody’s Investors Service, and “Second Best Place to Raise Kids,” from Business Week (2008).

Nevertheless, it was clear in 1985 that an economy based on heavy manufacturing was over. The often-quoted dictum from the richest American ever, Andrew Carnegie — “Put all your eggs in one basket, and then watch that basket” — does not apply if the eggs and the basket have disappeared. In the 1980s, Pittsburgh still had the key indicators of quality of life, but if well-paying jobs continued to disappear, so would quality of life.

Something had to be done, and it was. Between 1985 and 1995, the regional economic agenda for the next 25 years was set. This process involved leaders in the public and private sectors, in much the same way Renaissances I and II had. But something else also began to happen — an unprecedented bubbling up of quality-of-life initiatives from individuals, volunteer groups, and nongovernmental organizations, many of them in turn funded by the corporations and foundations. There was receptivity to new things and willingness to take risks. This bottom-up energy was especially exhibited by young adults in their twenties and thirties who...