- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Block Parties examines young children's spatial development through the lens of emergent STEAM thinking. This book explores the physical and psychological tools that children use when they engage in constructive free play, and how these tools contribute to and shape the constructions they produce. Providing readers with the tools and understanding necessary to develop children's spatial sense through the domains of mapping and architecture, this cutting-edge volume lays the groundwork for both cognitive development and early childhood specialists and educators to develop more robust models of STEAM-related curriculum that span the early years through to adolescence.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Discovering STEAM in the Early Years

DOI: 10.4324/9781003097815-2

The true poem is the poet’s mind; the true ship is the shipbuilder. In the [person] we should see the reason for the last flourish and tendril of [her/his] work.Ralph Waldo Emerson

Young Children as Active Agents of STEAM

Nate, 5 years and 1 month of age, attends a preschool in an urban community for both low-income and middle-income families. He thus has the opportunity to interact with a diverse group of children and benefit from the many resources afforded by the preschool. On the surface, Nate certainly has his share of confidantes on the one hand and adversaries on the other. But what makes Nate unique is that he is able to express his spatial and cartographic ability and architectural prowess with minimal interaction with peers.

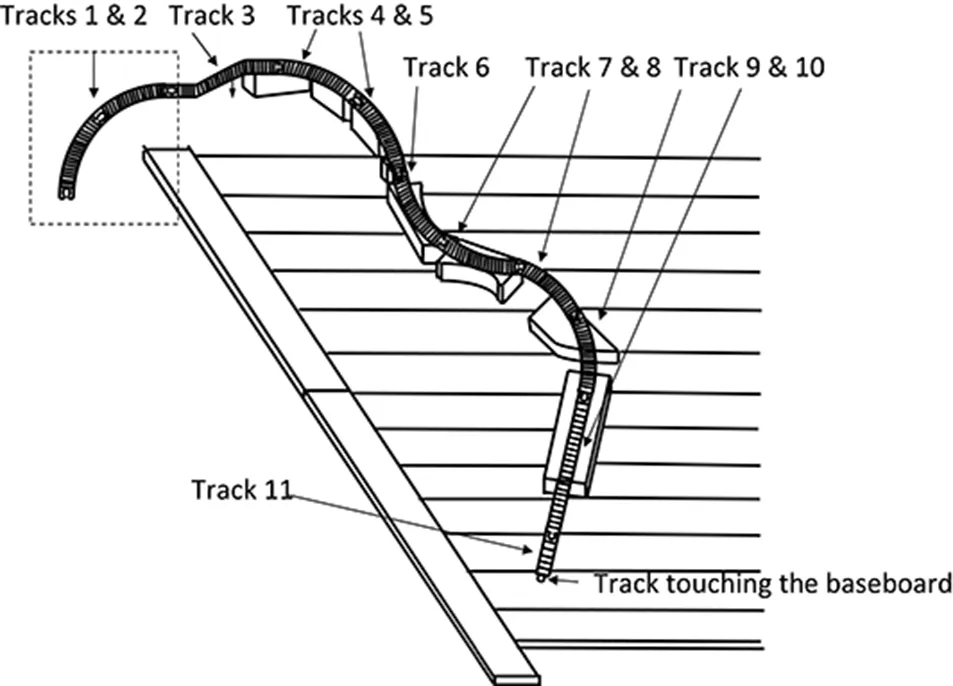

While looking for more logs in the bins, Nate stumbles upon two wooden pieces of railroad track. Although these pieces are attachable, Nate does not connect the pieces immediately. Through trial and error, Nate finally attaches the two pieces of track (Track 1 and Track 2). He places this track on a section of the classroom floor where he can work.

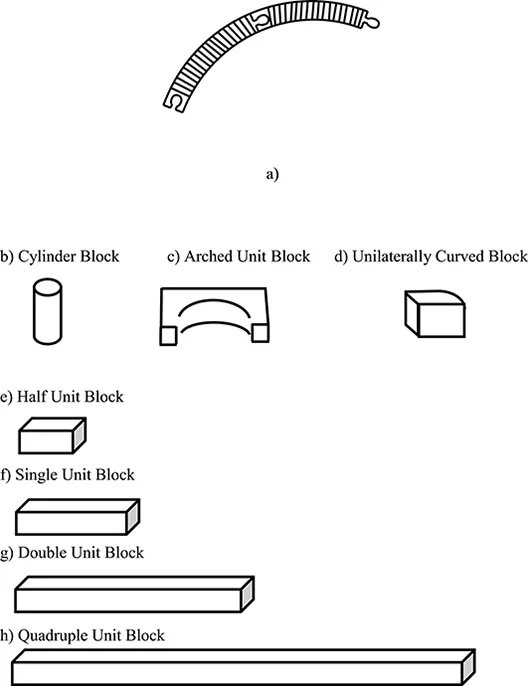

After placing the initial connected pieces of track on the floor, Nate returns to the block cabinets. He is stationary for approximately 30 seconds. He appears to be in deep thought. Instead of taking more pieces of track, Nate takes two cylinder blocks and two indented arch blocks, and brings the four pieces to the floor area where he is about to work. Nate then picks up an undulated, as opposed to flat, track piece (Track 3) that is lying on the floor near his work area, and attaches it to the two initial pieces. The piece is undulating in that it curves in a vertical fashion—like in the form of a hill—and not as a flat, non-bending curve. Subsequently, he takes a small flat, curvilinear piece of track, which curves in a horizontal manner, and attempts to attach it to the undulated track piece. Nate says “Hi” to José, one of the teachers’ aides. Given that one end of the unfinished track system is left suspended in mid-air, Nate takes a unit block that had been also lying nearby, and places it under the suspended track, and uses the unit block as a support, or foundation, for the suspended part of the track system. Initially, he is unsuccessful in supporting the track, because the positioning of the unit block (large face down) left a gap so that the track remained suspended. Nate turns the unit block (medium face down), and at this point, he successfully supports the track with the block. To get a better idea of the types of visuospatial constructive play objects (VCPOs) (Ness & Farenga, 2016) Nate uses for his make-believe roller coaster, see Figure 1.1. (See Chapter 3 for a more complete definition of VCPOs.)

Nate returns to the block cabinets and bins to search for more track. He pauses, again in deep thought, for approximately 30 seconds. Finally, he finds a fifth piece of track—flat track. Before he connects this flat track, he knows that he needs another support. Nate reaches into a nearby cabinet, and does not find a block to his liking. He then finds a unit block nearby on the floor, which seems to work as a support. There is a problem however: The space underneath the track does not allow the supporting block to be positioned in the direction he had intended—i.e., in the same direction as the track. So, Nate turns the supporting unit block approximately 45 degrees so that it fits in the narrow space. In doing so, Nate attempts to support the joint between Track 1 and Track 2 using the unit block placed in a 45-degree position. He realizes however that the weight of Track 2 will not be fully supported. Nate then pulls the unit block out. But this is only temporary, because the real obstacle for Nate is the first of 13 quadruple blocks that are touching and placed parallel to each other. The quadruple block is the longest piece in the standard block set. Other blocks include double unit blocks (half the size of quadruple unit blocks), unit blocks (quarter the size of the quadruple), and half unit blocks, which are one-eighth the size of quadruple blocks (see Kathryn’s case study below and Figure 1.4 for a more elaborate description of block sizes). This group of quadruple blocks is referred to here as the “landscape,” for it serves as one part of the structure’s ground setting—the other being the floor. So, Nate removes the first quadruple block, so that the supporting unit block could be positioned in the direction that he initially planned. The supporting unit block is placed in the original position and Track 2 is now attached and partially supported. Track 2 is not fully supported because part of it is suspended over the “landscape”—the remaining parallel, and touching, quadruple blocks. To support the suspended track, Nate takes a unit block, and initially places it on the supporting unit block, but then realizes that this would prevent the continuation of track. He then removes it and places this small one-quarter unit block in the correct location—on the landscape as a means of supporting the suspended part of Track 2. At this point, Track 2 is successfully in place. Nate carefully inspects all the joints to ensure that they are secure. The episode ends as Nate tells one of the teachers that he is making a roller coaster: “Latucia, look [at] what I’m making! I’m making a roller coaster!”

The above episode of Nate’s construction of his roller coaster structure represents a telling example of a preschool aged child who exhibits a propensity to construct like an engineer, design like an architect, and map like a navigator. But all his successes as an emergent engineer, architect, and cartographer come at the price of trial and error, perseverance, and the ability to learn from miscalculations in the construction process.

Figure 1.1 Wooden pieces of “track,” support blocks, and landscape blocks in Nate’s roller coaster structure

One major element of Nate’s episode has to do with the way in which the boy grapples with physical obstacles that seem to frustrate the continuation of the roller coaster system. The obstacle issue arises as Nate takes a unit block on the floor and attempts to use it as a means of supporting “overhead” track, particularly the joint that connects two pieces. He deals with this situation in two ways. In the first way, Nate deals with the oncoming wooden block “landscape” (which is approximately 2 or 3 inches above the floor landscape) by turning his “material”—namely the unit block support, so that overhead track can continue onto the wooden block “landscape.” This method of support could have been successful; however, Nate was still dissatisfied. He seemed wary about the positioning of the support. He then deals with the situation in a second way, one which involves the altering of the “landscape.” Nate’s decision to alter the landscape for the continuation of the roller coaster system is one of the several unique aspects of this videotaped segment, one that clearly demonstrates the child’s knowledge of architectural principles. (See Figure 1.2 for sequence of events regarding the removal of a piece of “landscape.”)

Figure 1.2 Sequence of events relating to Nat’s removal of a piece of “landscape” (dashed lines indicate chronological sequence)

It should be noted that analysis of Nate’s cognitive behaviors and his experiences with model wooden train track and wooden play blocks are based on the method of naturalistic observation. Cultivated, developed, and advanced by Lincoln and Guba (1985) and innovated by Ginsburg and his colleagues (Ginsburg, Inoue, & Seo, 1999, Ginsburg, Pappas, & Seo, 2001, Ginsburg, Lin, Ness, & Seo, 2003), naturalistic observation methodology provides the researcher and practitioner with a panoramic vista that accentuates the everyday, spontaneous emergent thinking that is made evident as the child is engaged in free play.

In one respect, naturalistic observation can be used as a means of collecting data on some aspect of cognitive or social development that is of interest to the researcher. For example, Ginsburg and colleagues (Ginsburg et al., 1999, Ginsburg et al., 2001, Ginsburg et al., 2003) were interested in identifying mathematically related activities that children have the potential to engage in during free play. They investigated the extent to which specific, individual four- and five-year-old children engaged (or did not engage) in an emergent, mathematically related activity by examining minute-by-minute segments that were part of 15-minute excerpts for each child. Moreover, they were able to study possible socio-economic status (SES) differences in terms of time spent on one or more of six different types of emergent mathematical areas (i.e., enumeration, classification, pattern and shape, dynamics, magnitude/comparison, and spatial relations).

In addition to conducting naturalistic observation methodology for the purpose of quantitative analysis, naturalistic observation can also be extremely useful in studying spontaneous science, technology, engineering, arts/architecture, mathematics (STEAM) related activity, particularly exhibited by children who spend more than one-third of their free-play time with VCPOs. Such investigations offer what Geertz (1973) would refer to as a thick description of the goings on in the environment of the individual—in the present case, a four-and-one-half-year-old child. They can offer rich insight as to how a particular child constructs her model structure and to what extent that particular child’s model structure resonates with the architect’s blueprint or the cartographer’s map.

Getting back to the case of Nate, we ask: How does Nate deal with the landscape? Within the context of the preschool classroom, Nate’s “landscape” is the floor area of the classroom that is surrounded by the area’s block cabinets. This “landscape” includes the floor itself, as well as 13 parallel, touching quadruple unit blocks whose ends are leveled by two quadruple blocks on one of the two sides (Figure 1.3).

Two types of architectural principles are evident here. First, Nate clearly shows his understanding of support, that is, the notion that overhead constructions need a form of support in order to remain standing and not fall down. He creates support (through the use of unit blocks) in the form of posting (see Chapter 6), similar to the posts or towers that support different types of bridges. Second, Nate’s ability to employ techniques of engineering (another architectural principle described in Chapter 6) is exhibited in this part of the episode. This is evident through his seemingly skillful manipulation of the “landscape,” and his method of determining whether the support block will fit between another support block and the “landscape” as a means of sustaining overhead track (informal measurement).

Figure 1.3 Nate’s roller coaster structure and platform

Although Nate has removed a piece of the “landscape,” his problem of supporting the overhead track is not completely solved. This is due to the fact that the support for Track 5 on the floor is taller than the distance from the floor to the surface of the wooden block “landscape.” Thus, Track 5 remains partly suspended over the “landscape.” Nate seems to have learnt from past experience that a large unit block would be too large to support track suspended over the “landscape”; clearly, the suspended distance is less at this position than...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Discovering STEAM in the Early Years

- 2. Play Matters

- 3. Blocks, Bricks, and Planks: Visuospatial Constructive Play Objects

- 4. Simple VCPOs Are Best

- 5. Young Children Think Like Scientists and Mathematicians

- 6. Young Children Think Like Architects and Engineers

- 7. Coding STEAM during Constructive Free Play

- 8. Promoting STEAM Play with VCPOs: What Children Can Tell Us

- Appendix A: Inquiry Indicators for Early Childhood STEAM

- Appendix B: Constructive Materials Play Attitude Scale—CoMPAS

- Appendix C: Constructive Play Materials Inventory — Parents (CPMI-P)

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Block Parties by Daniel Ness in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Early Childhood Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.