This book is part of a longer project that was launched 12 years ago. In 2007, we surveyed the attitude of full-time law students toward crime, criminal justice and law enforcement, and in 2010, we compared and analyzed differences between the attitudes of a representative sample comprising 1,000 people and one comprising 100 lawyers. These studies focused on certain psychological characteristics, such as alienation, self-esteem, modes of thought, open/closed mindedness and the need for autocracy, while attitudes toward the duality of globalism and parochialism were also explored. Five years later, in 2012, the survey was repeated, and we compared the findings of the two studies. The present volume is, likewise, a sequel to the study based on the representative sample of the general population. All four studies are essentially longitudinal in character. This method provides, we believe, an empirically verifiable worm’s-eye view of how the population’s perception of society and their role within it has changed in eight short years.

1.1 What kind of research is behind this book?

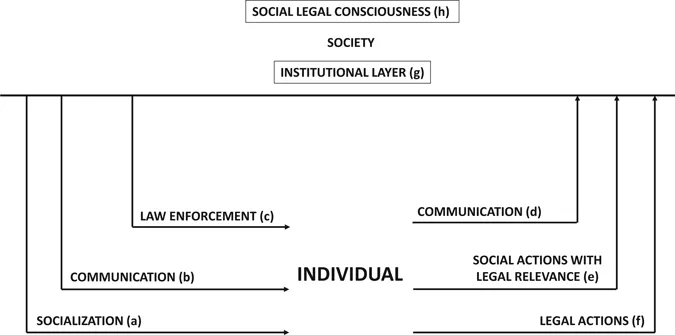

All three previous publications were billed as “social psychological research” in their subtitles and the present volume continues with this approach. Of course, psychology covers a large number of fields and methodologies, and reflects the tradition of thinking about society in two basic ways. One approach is societally centered, while the other is focused on the individual. The former emphasizes the primacy of groups, institutions and social structures over individuals, whereas the other assumes primacy of individual processes and functions over these societal aspects. Social psychology tends toward examining the world in broader social terms, for it studies social relations and the interaction between individuals. Our study explores opinions about and attitudes toward legal and political institutions in Hungary. It is, in other words, classical attitudinal research. Attitudes derive from acts of evaluation with cognitive, affective and behavioral components. But why are such subjective attitudes so important? Well, attitudes, rightly or wrongly held, manifest themselves in behavior toward others, while for an individual, attitudes define perception, thought and even physical behavior. If we know the attitude of others on an interpersonal level, the world opens up for us, and when it comes to interactions between groups, our attitudes toward our groups and toward other groups play a key role in cooperation, conflict and competition. Perhaps the greatest strength of this attitudinal approach, however, lies in the fact that it does not impose particular theories on people, but rather allows their options to speak for themselves.

Social psychological research has three basic types – descriptive, correlational and experimental – and our study is correlational. Correlational research does not identify causal relations; instead, it wants to establish correlations between two factors linked to the same, psychologically relevant phenomenon. To describe these methodologies in more detail, it is necessary to distinguish between strategies of social psychological research. There are three methodological types: survey, quasi-experiment and actual randomized experiment. The difference between these lies in the degree to which we can make general statements about a given population and the extent to which we can draw causal conclusions. Basically, this book offers a survey that identifies certain correlations between a variety of social factors.

1.3 The Rule of Law Report: Europe’s view of Hungary

It remains necessary to situate our study in its immediate political context, which is a challenging task, since this context is mutable, especially in these times of international crisis. It is worth mentioning the 2019 European Commission’s report on Rule of Law Report (the “Report”), which was published in September 2020, as part of its efforts to survey and present member states in the European Rule of Law Mechanism. The Report does not offer a positive image of Hungary, and the Commission expressed deep concern over a number of issues in relation to the rule of law. Naturally, the Commission’s report did not survey the population’s opinions, but rather considered shifts in the structure of the legal system that have taken place over recent years. Their way of assessing the situation in Hungary was, in other words, top-down, whereas our approach has been bottom-up. Yet, the population’s pessimism regarding whether the judicial system was becoming more or less corrupt seems to have some basis, given the restructuring of the criminal justice system that has been going on behind the scenes.

In the first part, the Report reviews the Hungarian justice system and questions its full independence. It finds it worrying that the Chair of the National Council of the Judiciary (OBT) has too much responsibility in its central management of courts and finds it highly problematic that the members of the Hungarian Constitutional Court can, once they leave office, continue working as judges at the Kúria, Hungary’s supreme court, without a standard appointment procedure, since the appointment of judges in the Constitutional Court requires the support of the legislative and the executive powers. Thus, the three “classical” branches of power meld because the Parliament and the government can, through their political preferences, influence the composition of the supposedly politically independent Kúria. As a consequence, the constitutional principle of the separation of the three branches of power does not prevail, though it is only fair to point out that the Report views the new systems and procedural solutions enacted within the past five years positively, so it would be too simplistic to conclude that there has been a straightforward power grab by the executive branch of government in recent years. Still, clearly, things are not quite as transparent as they should be.

The second part of the Report discusses corruption. It concludes that the rate of Hungarians who believe that corruption is a significant problem is higher than the European average, a finding that is wholly borne out by our statistics. This devastating view is echoed by numerous European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF) reports, and the Rule of Law Report emphasizes that while several organizations prosecute corruption, statistics reveal that the Attorney General’s Office does not do its task efficiently enough. In addition, the Report observes that despite the detailed regulations concerning declarations of wealth, related controls are limited and unsystematic. Furthermore, the National Anti-Corruption Strategy, as announced by the government for 2020–2022, does not extend to the several areas most frequently associated with corruption.

The third part of the Report dwells on media pluralism, and it is sharply critical of the governing party’s influence over the selection of the members of the Media Council of the National Media and Info-Communications Authority (NMHH), since the majority party in parliament can influence the composition of this prestigious committee. Furthermore, the Report observes that the “independent media” is subjected to systematic obstruction and intimidation, although this is not strictly a legal problem so much as a sociopolitical one.

Finally, the Report examines the system of checks and balances. It briefly outlines the details of the Emergency (in effect between 11 March 2020 and 18 June 2020) and some of the legislative developments that followed from this, but it does not take a position on this issue. It also investigates the work and the legal status of the Commissioner for Fundamental Rights. Statistical figures and legal regulations suggest that the ombudsman does not efficiently protect fundamental rights, such as freedom of expression, but at the same time, this fact does not mean that, in the words of the Report, “it does not make adequate efforts to protect all human rights”.

Indeed, according to the Report, there is significant pressure on civil society and, citing another report, it claims that the current political power has launched a clear offensive against the civil sphere, curtailing the full exercise of human rights by both legal and practical means. However, these comments are not related to the system of checks and balances because instead of concerning themselves with the legal dimensions of state organizations, they focus on public affairs and events taking place within the sphere of the freedom of opinion. For the European Commission, the rule of law means that the same law is applicable to all members of society, including governments and parliamentary representatives. If the rule of law means this, then Hungary meets these criteria because, according to the law, all individuals, including political leaders and officials, are accountable if they violate norms. At the same time, it is important to mention that the Constitutional Court took the following position in its 11/1992. (III. 5.) AB ruling: “To declare that Hungary is governed by the rule of law is at once a factual statement and a program [for improvement]”. Nearly 30 years after this ruling, the realization of this is still work in progress.

In addition to the numerous obligations that Hungary must fulfill due to its membership in the EU, a new system of state organizations has been established, new laws of procedure have been enacted and several important legal codes have been combined into new, twenty-first-century versions. It is, therefore, too simplistic to assert that Hungary’s legal system is wholly corrupt, but it undoubtedly remains hamstrung by an inheritance of centralization and nepotism, which unscrupulous politicians and members of the judiciary could exploit to their full personal advantage.

Objectives

This book is the fourth cycle of a project launched in 2007. Its main objective is to get a better understanding of how the Hungarian population thinks about the law and of the changes that took place in these opinions between the spring of 2010 and the autumn of 2018. Our study hopes to contribute to the growing interest in legal consciousness and legal culture that the social sciences, especially sociology, social psychology, political science, criminology and legal sociology, have shown in recent years.

The 2018 phase of the project aimed to turn the 2010 national representative survey into a longitudinal study by collecting data using a very slightly modified questionnaire, which considers, in particular, the power of social media, and draws on a representative sample. From a theoretical perspective, our study registers changes in socio-demographic, psychological, social psychological factors and in opinions about crime, criminal justice and the prevention of crime by comparing data from 2010 and 2018. Beyond this, there is no further agenda. In other words, we do not attempt to provide interpretation or theorization of the changes, but essentially limit ourselves to the identification of “correlations” or “sociological patterns” that make further analyses and hypotheses possible. First, however, the study positions itself in the context of contemporary international (and Hungarian) legal sociology and criminology, so as to contribute to a broader understanding of the shifts in perception of civil society and the rule of law during Fidesz’s ascendency.