Matthew V. Kroot and Cameron Gokee

This article examines the construction of historical narratives on local, national, and international levels and the ways that archaeological materials and cultural heritage sites can be included within conversations and debates about how to represent the past in the present (e.g., Harrison 2012; Smith 2006). Specifically, we address a notable disconnect between the interpretive histories shared in local communities and those presented by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) when discussing the past of the Bandafassi region in southeastern Senegal. A portion of the Bandafassi region - the cultural landscape of Bassari Country - was inscribed onto the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2012 (UNESCO World Heritage Centre 2012). While the supporting documentation and public presentation of Bassari Country by UNESCO makes no direct mention of the role of slavery and its associated social processes, we show that local histories and archaeology can be used to argue that this region is indeed a landscape of slavery.

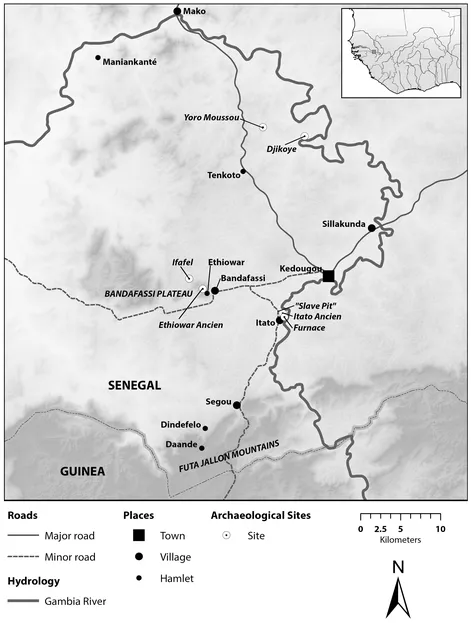

We present work from the Bandafassi Regional Archaeological Project (BRAP), located in the administrative district (arrondissement) of Bandafassi, Senegal (Figure 1).

Bandafassi district shares its place name with a specific village and plateau within its confines. Presently, the Bandafassi district is a multiethnic region, which includes major Bedik, Bassari, Malinké, Peul, Jallonke, and Jakhanke linguistic communities. BRAP focuses its research on how regional and global entanglements during the second millennium CE affected village-based societies of this region. Goals for the project include analyzing how external forces and processes acted upon local communities, how local actors utilized newly available social structures and relationships to their own ends, and how newly arriving people, often embedded within and enacting regional and global entanglements, were absorbed into local social dynamics.

Theoretical perspectives: On landscapes of slavery

Bassari Country has been labeled by UNESCO as a cultural heritage landscape, a term not originally included in the potential types of World Heritage sites. As described by Rossler (2002), it was not until 1992 that UNESCO recognized cultural heritage landscapes. At that time, there was a desire within the World Heritage Committee to move away from monuments as a primary object of inscription. Such a practice was seen to be Eurocentric and to have produced a list of sites biased towards certain values that were exclusionary, chauvinistic, and not representative of the full spectrum of human achievement. The landscape concept for cultural heritage opened up new possible forms of valorization and preservation including human relationships to the natural environment, land management practices, the practices of living communities, meaning-making tied to the physical world, and the inclusion of large swaths of the world previously excluded from recognition (Rossler 2002, 10).

Many of these themes can be seen in the official UNESCO description of the "universal value" of Bassari Country; universal value is one of the basic criteria that UNESCO uses for determining if a site or practice is worthy of inscription. The values identified for Bassari Country include the "respectful and sustainable use," "complex interactions," and "sacred dimensions" of landscape-based practices (UNESCO World Heritage Centre 2012). It is also important to note that Bassari Country is located in one of the three regions (Africa) specified as previously underrepresented in the World Heritage list (Rössler 2002, 10). Thus, the concept of the landscape and, specifically, the meaning of the cultural landscape of Bassari Country are central to the official history propounded by UNESCO. In this article, we argue that the landscape perspective provided by UNESCO in official documentation implicitly silences a major driving force of the specific social formations found across Bandafassi: slaving processes. Historical and archaeological data generated by BRAP show that slaving processes and the political and economic forces behind them heavily impacted the region. So, while the official statements of UNESCO do not reference it, Bandafassi is indeed a landscape of slavery.

What is a landscape of slavery? Landscape perspectives are some of the most frequently invoked research frameworks within archaeology, with a long history in the discipline (e.g., David and Thomas 2008). Landscape archaeologies can focus on the physical, spatial, and social structural aspects of landscapes in which past actions, events, and social processes occurred. They can also encompass the understandings of these physical landscapes as well as meaning making and meaning-manifesting practices by those participating in such events and social processes (Knapp and Ashmore 1999). Thus, landscapes of slavery are the physical and cultural landscapes affected by social processes associated with slavery and/or meaningfully encoded with understandings of slavery.

As a word that generates great academic interest and creates strong emotions and judgements, slavery is difficult to pin down. It is often said that within the Anglophone world this word conjures up associations with the de jure and practical aspects of antebellum chattel slavery in the American South (e.g., Kopytoff and Miers 1977, 3; Marshall 2015, 3). However, when attempting to utilize this word within the African context, the challenge becomes understanding when it should be invoked to characterize systematic and widely repeated structural relationships that developed in communities far removed from the word itself and the many legal and cultural practices that shaped its definition. Additionally, even when talking about the heavy impact of the Atlantic system in West Africa, the impact was not uniform in its manifestation across the region.

There have been numerous discussions of this issue (Kopytoff and Miers 1977; Marshall 2015; Patterson 1982; Rodney 1966). Recent works, especially in archaeology, have elected to view slavery as defined by captivity and coercion, viewing such a broad definition as allowing for a wide variety of phenomena to be productively compared (e.g., Marshall 2015, 2-3). Perhaps no quote better captures the essence of why the word slavery has been seen as an appropriate label for many different forms of social relations found across human history than that of Kopytoff and Miers (1977, 67), when they describe, "Acquiring people by means other than marrying or begetting them and more or less forcibly putting them to some use." One might add that there is a total loss of labor power by the enslaved in that they cannot unilaterally pull out of the relationship. This more general definition relieves us of the gray area with such things as financial incentivization via asymmetrical economic relationships.

With such a broad definition, it is hardly remarkable to find historical evidence of slavery in many places and times. While this allows for productive discussions that can cross disciplinary boundaries (Marshall 2015, 1), the specifics of any given context must also be considered when attempting historical interpretations of causation. Much historical and anthropological research has highlighted the variability in institutions of slavery in the African context (e.g., Kopytoff and Miers 1977; Lovejoy 2012). Interestingly, while Africa is so central to the Atlantic system, the variability of the institution within the continent has forced many scholars to move beyond the identification of slavery through a static classification or a bundle of features. Instead, authors have advocated for what has been termed a processual approach to slavery, whereby the object of study is not slavery itself, but the effects of captivity, coercion, and the loss of labor power for large swaths of communities and their local social dynamics (Kopytoff and Miers 1977, 60; Marshall 2015, 2; Stahl 2008, 39).

Such a theoretical maneuver has been productive within archaeology (e.g., Monroe 2015), as the material signatures of slavery - that is, the ways that archaeologists can definitively identify captivity, forcible coercion, and the total loss of labor power without written, oral, or visual references - are quite rare and often interpretively ambiguous (Alexander 2001, 56-57; Gijanto 2015; Stahl 2013, 2015). If we know that slavery and its associated social phenomena, such as the slave trade and slave raiding, are at work in a place, what can be seen is how this constellation of social forces can act upon and transform society. The written and oral historical records demonstrate how the long arm of the Atlantic system reached, if indirectly, into the lives of small-scale, non hierarchical, and decentralized (often times termed acephalous) societies throughout Africa (see examples in Diouf 2003).

It is in this sense that we invoke the term here in our claim that the Bandafassi study area, including the Bassari Country UNESCO World Heritage Cultural Landscape, was a dynamic landscape of slavery during at least the past several centuries. Slavery's impact is apparent both in local oral historical accounts and in archaeological data. Local inhabitants note extensive and specific histories of slave raiding and often interpret prominent spatial and material features of the landscape as having been produced by slaving processes (Altschul, Thiaw, and Wait 2016; Balde 1975; Barry 1998; Carpenter 2012; Harrison 1988; Rodney 1966, 1968). Probable material manifestations of slaving processes, such as site fortifications and defensively positioned hilltop settlements, are some of the most striking parts of the built environment of the BRAP study area. Additionally, many of the collective actors identified in local histories, such as the Islamic revival state of the Futa Jallon, consistently and extensively integrated slavery into their social systems and slave-taking into their military actions.

A more complicated question is how this history is used or not in the present by different interested parties. In order to answer this question, we compare several interpretive discourses, including those presented to tourists by local guides in the Bandafassi region, those found in the Bassari Country application and assessment process for World Heritage status, and the official narrative of the history of Bassari Country by the UNESCO World Heritage Committee. To these ends, this article will start by introducing the geography, ecology, and contemporary social formations of Bandafassi. We will then present and analyze the previous historiography of the region, with special attention to the ways that ethnicity has been a central organizing concept in the work. The next section, focusing on the original archaeological and historical data generated by BRAP, will show how this work can highlight the impacts of slavery on the cultural landscape of the region. By analyzing these various lines of evidence together, it is possible to reframe histories to focus on the effects of large-scale processes on local actors and the agency of local actors entangled within regional and global phenomena.

We are examining Bandafassi as a landscape of slavery in order to interrogate silences in various institutional and local discourses. In doing so, we remain aware of the risks of projecting our own situated (in this case American) interests onto the archaeology of the region (Richard 2018). Thus, while we argue that slavery profoundly shaped the historic landscape of Bandafassi, we do not deny that many other social processes unrelated to slavery, such as those emphasized by tour guides and UNESCO's World Heritage documents, were also central to the historic production of Bandafassi's social systems. Local concerns especially, be they related to narratives of the past or the uses of the past in the present, hold special weight and must be acknowledged.

The BRAP study area

Bandafassi lies in southeastern Senegal, where dolerite plateaus rise above the plain surrounding the upper Gambia River, as it descends from the Futa Jallon mountains to the south. These landforms make for a mosaic of upland, lowland, and riparian habitats within the broader Guinean savanna forest complex (Kowal and Kassam 1978). Temper tatures vary by season, with the average high temperatures peaking at 40°C or more in April, near the end of the dry season, and dropping to 30°C in August, during the height of the rainy season. Seasonal rainfall provides anywhere between 500 and 1500 mm of precipitation during the June-to-October portion of the West African monsoon cycle (République du Sénégal 2011).

This diverse regional geography sustains an equally diverse array of subsistence possibilities for agricultural producers and nomadic pastoralists. The primary constraint on agricultural productivity in the area is water. Summer monsoon rainfall and surface water sources provide enough moisture for growing crops such as millet (Pennisetum glaucum), fonio (Digitaria exilis), cotton (Gossypium spp.), peanuts (Arachis hypogaea), and rice (Oryza sativa), depending on local social, infrastructural, and environmental conditions. Most soils are not amenable to intensive cultivation and shifting cultivation is common in the area. The savanna forest and Gambia River provide wild game, plants, fish, honey, and palm wine, as well as grazing lands for livestock. Livestock are generally smalle...