eBook - ePub

British Art and the Environment

Changes, Challenges, and Responses Since the Industrial Revolution

This is a test

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

British Art and the Environment

Changes, Challenges, and Responses Since the Industrial Revolution

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book explores the nature of Britain-based artists' engagement with the transformations of their environment since the early days of the Industrial Revolution.

At a time of pressing ecological concerns, the international group of contributors provide a series of case studies that reconsider the nature–culture divide and aim at identifying the contours of a national narrative that stretches from enclosed lands to rising seas. By adopting a longer historical view, this book hopes to enrich current debates concerning art's engagement with recording and questioning the impact of human activity on the environment.

The book will be of interest to scholars working in art history, contemporary art, environmental humanities, and British studies.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access British Art and the Environment by Charlotte Gould, Sophie Mesplède, Charlotte Gould, Sophie Mesplède in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & European Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

From the Claude Glass to Drones

Framing Environmental Encounters

Figure P.1 Aliki Braine, Draw Me A Tree (Black Out), 2006. Black and white photograph with hole-punched negative, 85 × 107 cm.

Source: Courtesy of the artist.

1 Vehicles of Truth

Portable Studios and Nineteenth-Century British Landscape Painting, 1856–1885

The nineteenth century witnessed a dramatic rise in the number of artists who left the studio to paint outdoors. Artists associated with movements as diverse as the Barbizon School, the Hudson River School, Realism, Pre-Raphaelitism, Naturalism, and Impressionism all engaged in plein-air practice to varying degrees. Various apparatuses were devised to facilitate artists’ excursions into nature; parasols, collapsible easels, and portable paint tubes and boxes were marketed to professional and amateur artists who sketched outdoors.1 A nineteenth-century invention used for landscape painting that has received less scholarly focus is the portable studio. Portable studios offered a solution to the problems that artists encountered working outdoors, such as inclement weather and the investment of time required to travel to painting sites. This chapter examines the portable studios of British artist and critic Philip Gilbert Hamerton (1834–1894) and German-born British artist Sir Hubert von Herkomer (1849–1914). I argue that in addition to addressing practical issues, portable studios were equally an attempt to resolve theoretical dilemmas, specifically those posed in John Ruskin’s Modern Painters (1843–1860). Ruskin’s revised definition of truth to nature provided artists with new criteria by which to interpret the observable world. A central question that arose from the volumes was how artists were to visually discern and to represent Ruskin’s ideal of truth. To approach this truth more directly, some artists reimagined the very space through which they perceived and represented the world, transforming their studios into optical instruments that could be situated within the landscapes they painted.

In addition to Ruskinian principles of truth to nature, portable studios are located at the intersection of a number of nineteenth-century discourses. As I will argue in this chapter, their invention was embedded in period debates surrounding the role of photography in art and the technological mediation of nature.2 Hamerton (1897) claimed that he wished “to do what had never been done, to unite the colour and effect of nature to the material accuracy of the photograph” (236). Only five years before Hamerton conceived of his studio for landscape painting, the photographic collodion process was introduced and became a competing mode of representation. Portable studios were also indebted to the valorisation of efficiency that emerged with new technologies and industrial capitalism. Designed in theory to increase painterly productivity by reducing time spent travelling to sites and days lost due to weather, portable studios rarely yielded such results in practice. Rooted in the capitalist drive to production, their invention also satisfied the concomitant bourgeois desire to escape to nature as an antidote to industrialisation prior to the popularisation of recreational camping as a leisure activity around mid-century.

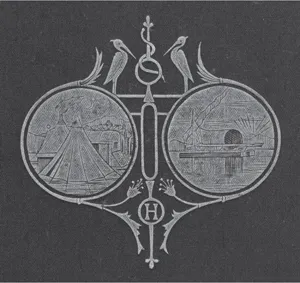

Hamerton originated the idea of portable studios for landscape painting and shared the concept in A Painter’s Camp in the Highlands, and Thoughts about Art (1862). Although Hamerton is primarily remembered for his contributions to art criticism, A Painter’s Camp documents his earlier ambition to pursue a career as a landscape painter. The book details Hamerton’s experiences using his portable studio beginning in the fall of 1856, when he first tested the apparatus near the border of Lancashire and Yorkshire. The studio is pictured on the cover of the book’s first and second editions; two decorative medallions depict Hamerton’s camp as it appeared in 1857 on the island of Inishail in Loch Awe, Scotland. The medallions resemble circular lenses, alluding to Hamerton’s interest in natural optics and simulating the effect of looking through binoculars. The artist’s purpose-built studio boat is depicted on the right; the other side shows his painting hut, with its arched roof and two circular air vents, positioned behind a pair of tents. The tent in the foreground was used as a kitchen and the tent in the middle ground was used by Hamerton’s servant, whose labour made such an enterprise possible. The painting hut was made of two-and-a-half-foot-square wooden panels that were stacked and transported to and from painting sites by horse or, Hamerton (1862) proposed, “even on men’s backs” (1:7). Crucially, the studio had four two-and-a-half-foot-square plate-glass windows that were bolted to the panels on assembly and that enabled Hamerton to view the surrounding landscape from inside. By including four windows instead of one, Hamerton aimed to maximise time spent painting; if one window became covered with rain drops, he reasoned that he could look out of a different one and continue to work (1:6–7, 1:21).

Weather was a never-ending vexation for Hamerton. “Water and air are filled with a million foes,” he lamented (Hamerton, 1862, 1:75). It was not only weather but also insects that plagued his efforts as a landscape painter. His complaint recalls John Everett Millais’s (1829–1896) drawing entitled Awful Protection Against Midges (1853), which depicts two artists afflicted by a swarm of flies as they sketch outside. The Pre-Raphaelites were particularly devoted to the principle of painting directly from nature, with Ruskin ([1854] 1904) once stating that “every Pre-Raphaelite landscape background is painted to the last touch, in the open air, from the thing itself” (157–8). In search of a solution to the problems associated with painting in nature, Hamerton (1866) recounts in A Painter’s Camp how he desired “something to shelter a painter from the wind and rain, and yet enable him to see” and that “this led to the devising of a hut for shelter, with plate-glass windows to see through” (xxi). Comparing the labour of an artist to that of a clerk or attorney, he reasoned that landscape artists also needed a comfortable environment in which to work:

Figure 1.1 Cover medallions of Philip Gilbert Hamerton’s A Painter’s Camp, 2nd rev. edn. London: Macmillan and Company, 1866.

Source: Collection of the author.

Let him take his papers out of doors some wild winter’s day, with nothing in the way of furniture but a portable three-legged stool and a portfolio. Let him carry this apparatus into the middle of some exposed field, and then apply himself as he best may, without shelter, in the rain and wind.

(Hamerton, 1862, 1:ix)

By improving the physical circumstances of landscape artists, Hamerton believed that the genre of landscape painting as a whole would be advanced.

Ruskin and Truth to Nature

The greatest intellectual influence on Hamerton in generating the concept of a portable studio for landscape painting was John Ruskin (1819–1900). After Hamerton purchased a copy of the first volume of Modern Painters (1843) in 1853, he accepted Ruskin’s views on art and became committed to working directly from nature. In that volume, Ruskin described the impact of art in terms of its ability to convey ideas to the spectator. He conceived of five distinct though related types of ideas, each of which represented a unique source of pleasure derived through the contemplation of art: ideas of power, ideas of imitation, ideas of truth, ideas of beauty, and ideas of relation. Ideas of truth, or “the perception of faithfulness in a statement of facts by the thing produced,” is the central and third of the five categories (Ruskin, [1843] 1903, 93). While Ruskin identified ideas of relation as the greatest of art’s impressions, he devoted the majority of the first volume of Modern Painters to elucidating ideas of truth in his defence of J.M.W. Turner’s (1775–1851) painting.

Although Ruskin did not consider it to be the noblest of the five ideas, truth occupied a position of precedence in his hierarchy. He maintained that “nothing can atone for the want of truth, not the most brilliant imagination, the most playful fancy, the most pure feeling” and that “no artist can be graceful, imaginative, or original, unless he be truthful” (137–8). Moreover, Ruskin argued that the truthful representation of facts was a discernible index of the more noble ideas of beauty and relation, thereby rendering truth a measure of general artistic value:

Truth is a bar of comparison at which [all works of art] may be examined, and according to the rank they take in this examination will almost invariably be that which […] we should be just in assigning them; so strict is the connection, so constant the relation, between the sum of knowledge and the extent of thought, between accuracy of perception and vividness of idea.

(138)3

Figure 1.2 Sir John Everett Millais, Awful Protection Against Midges, 1853. Pen and brown ink on medium, smooth, laid paper, 16.5 × 11.1 cm, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund, B1996.9.2.

In this statement, truth is distinguished by its visibility. However, Ruskin also described an invisible form of truth. Central to Modern Painters is the assertion that ideas of truth may be material or immaterial, relating either to outward appearance or to inner meaning (104). Ruskin described the latter variation as an inexpressible faithfulness to nature that exceeds language. Given this semantic limitation, he confessed that Modern Painters could only thoroughly address material truth.4 Yet it is immaterial truth that Ruskin valued most and instructed his readers to reproduce, declaring in the fourth volume (1856) of Modern Painters, that

the aim of the great inventive landscape painter must be to give the far higher and deeper truth of mental vision, rather than that of the physical facts, and to reach a representation which, though it may be totally useless to engineers or geographers, and, when tried by rule and measure, totally unlike the place, shall yet be capable of producing on the far-away beholder’s mind precisely the impression which the reality would have produced.

(Ruskin, [1856] 1904, 35)

Robert Hewison has described Ruskin’s theory as both materialist and idealist, arguing that it requires readers to recognise objects as “real and symbolic” (62). Indeed, at the basis of Ruskin’s aesthetic theory was his interest in the fundamental relation between the visible world and invisible ideas.

Ruskin acknowledged the difficulty of apprehending truth in nature, shortening the title of one chapter to “Truth not easily discerned.”5 Later volumes arguably did little to clarify these theoretical ambiguities. For instance, in the fourth volume Ruskin ([1856] 1904) warned readers that “it is always wrong to draw what you don’t see” (27). However, he stipulated that “some people see only things that exist, and others see things that do not exist, or do not exist apparently. And if they really see these non-apparent things, they are quite right to draw them” (28; italics in original). Regardless of one’s relative power of vision, Ruskin advised artists to “go on quietly with your hard campwork, and the spirit will come to you in the camp, as it did to Eldad and Medad, if you are appointed to have it” (29). It was this camping advice that Hamerton took literally and used as the epigraph to A Painter’s Camp. The apparent influence of Ruskin on A Painter’s Camp was so significant that one reviewer of the book described Hamerton’s writing as “Ruskinese” (“Robinson Crusoe Painter” 1863, 347).

Hamerton conceived of his portable studio for landscape painting “to get the utmost amount of attainable truth into [his] work” (Hamerton, 1862, 1:viii). He believed it would revolutionise how artists studied nature, declaring that he could “scarcely conceive the results to my success in art that may follow from this contrivance” (1:21). It would provide access to effects not previously available to artists:

For the study of snow in windy weather, when the drifts are most beautiful, it will be a most precious addition to my artistic apparatus, for I shall be able to sit comfortably inside, and still see my subje...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part 1 From the Claude Glass to Drones: Framing Environmental Encounters

- Part 2 Areas of Outstanding Industrial Beauty? A Layered History of Reappropriation and Profitability

- Part 3 Decentering Human Vision: Art in a Shared Environment

- Index