![]()

CHAPTER ONE

From Functionalism to Symbolism

The castle story

Much of this book relates the ways in which our thinking on castles has dramatically changed over a relatively short space of time and the reasons why this change has occurred. Before this can be done, however, it is necessary to recount, in very general terms, how previous generations have interpreted the medieval castle. At the risk of over-simplifying what is a complicated subject, it is fair to say that there has, for many years, been a castle ‘story’ that has been repeated countless times in books, television programmes and heritage displays. Certainly, it was the story that the author was led to believe as a schoolboy. Many of the premises central to this story remain influential today and some parts will be familiar to many readers.

The ‘story’ begins when the castle (along with feudalism, the social organisation which supported it) was introduced into England in 1066 during William the Conqueror’s invasion of England. In the Norman settlement that followed the victory at Hastings, William and his followers studded England with castles in order to pacify a potentially rebellious population. These castles were chiefly of motte and bailey type (the motte being an artificial mound of earth and the bailey the adjacent enclosure) which had the advantages of being quick to build and affording good protection for the invaders. Once the immediate danger of the Conquest had passed, however, new threats emerged, this time from the Norman barons themselves, who used their castles for private war. If the monarch was not powerful enough to subdue them, barons would usurp royal authority and fight each other (and the king), using their castles as bases. It was only in the late twelfth century, as siege weaponry developed, the costs of building in stone became prohibitive, and royal authority was strengthened, that the evils of private castle-building began to be curbed.

Thereafter the development of castles became an evolutionary struggle between attacker and defender: rounded towers replaced square towers to counter the threat of mining; the development of the gatehouse (Figure 2) reflected the need to protect the vulnerable castle gate; water defences became larger and more elaborate in order to prevent attacking engines from reaching the walls; concentric tiers of defences maximised defensive firepower from the ramparts. These developments achieved their apogee during the late thirteenth century with the castles built by Edward I in North Wales. Castles such as Conway (Conwy) and Beaumaris (Biwmares) represented the high point of medieval military architecture (Figure 3).

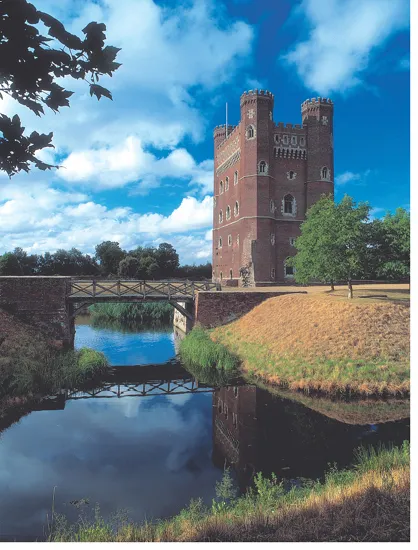

Thereafter, the castle went into decline. Warfare became characterised by battles rather than sieges (seen, for example, during the Wars of the Roses), cannon made the castle progressively more obsolete, and the buildings themselves increasingly made concessions to domestic comfort (Figure 4). Later medieval castles still reflected a concern to deter the more aggressive forms of local violence, but the fortified residence of the military magnate was slowly giving way to the country house. By the early sixteenth century, the strong Tudor monarchy had curbed the worst excesses of the medieval baronage and Henry VIII’s construction of a chain of artillery forts across his kingdom demonstrated that the state now had responsibility for war and national defence. The castle age, and therefore the castle ‘story’, was over.

The development of castle studies

As a way of explaining the changing nature of castles across the Middle Ages, the story outlined above is elegant, highly persuasive and remarkably enduring. It is, however, now open to reinterpretation at almost every turn. In order to understand why, it is necessary to examine where this story originated and why it has come to be questioned. There is a vast secondary literature on castles and what follows is only a brief examination of how the castle ‘story’ came into being.

The origins of castle studies

Castle studies, at least in its modern academic form, originated in the nineteenth century. Prior to this, castles had attracted the interest of travellers and antiquarian writers but were not a subject for serious academic study. For much of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries the image of castles was bound up with notions of the romantic and picturesque, embodied in novels such as Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe. As the nineteenth century progressed, however, general developments in the field of architectural studies, particularly in France, made castles a more acceptable subject for academic research.1 Yet their battlements, murder holes and arrow loops ensured that castles were studied primarily as fortifications, rather than integrated with the burgeoning study of the architecture of medieval cathedrals and churches. A new category of reference was invented for them: ‘Military Architecture’. Castles were the medieval equivalent of the artillery forts and bastions that appeared in Europe in the sixteenth century. This martial image of the castle also went hand in hand with then current theories about the nature of medieval society which stressed its violence: in the age of feudal lawlessness private war was the modus operandi of the robber baron and the castle was the brigand’s lair.

In British historiography one of the first significant studies on castles to appear was G. T. Clark’s Mediaeval Military Architecture in England (1884–85).2 Much of this two-volume work comprised a detailed survey of a range of sites across Britain and France, but an extended introduction charted castle development. Clark undeniably saw castles primarily as military structures and his treatment of individual buildings was clearly influenced by his background in civil engineering. Unfortunately his book is chiefly remembered for the fact that he suggested that mottes were pre-Conquest in date and this has sometimes overshadowed what was, for its time, a pioneering study.

Although Clark’s work was highly inventive, castle studies were to be dominated for decades by two books published in 1912 which set the ideological agenda for future generations. The first was Ella Armitage’s The Early Norman Castles of the British Isles. 3 In this innovative piece of work Armitage used a combination of Ordnance Survey maps and references to early castles culled from documentary sources to demonstrate that it had been the Normans who had introduced the castle to England. This was not an entirely new idea – the historian J. H. Round had taken Clark to task on this issue some years earlier in an article published in Archaeologia 4 – but between them Armitage and Round exploded the idea that mottes belonged to the Roman, Viking or Anglo-Saxon period. Moreover, Armitage’s work was not simply confined to the area of castle origins. She also discussed the siting and distribution of Norman sites and offered a tentative analysis of their landscape context. In this sense her work was truly groundbreaking.

The second crucial work was Alexander Hamilton Thompson’s Military Architecture in England during the Middle Ages.5 This was primarily a study of the upstanding structural remains of castle buildings, although it did touch on other areas, such as castle siting and morphology. In a particularly elegant argument, Thompson charted the ‘Darwinian’ evolution of the castle across the medieval period. He argued that the rationale behind developments in castle design was purely military: ‘it is obvious that, in the history of military architecture, any improvement in defence is the consequence of improved methods of attack’.6 This is a narrative that was to become very familiar in subsequent decades.

It is difficult to underestimate the impact of these three works on castle studies; all were, in their own way, highly influential. The disagreement over mottes aside, all three agreed on the military character of the castle. Thanks to Armitage and Round the castle was firmly established as a ‘Norman import’ and a tool of Conquest, while Thompson provided a template with which to explain the changing development of castles from the eleventh century to the end of the Middle Ages. It is to these great scholars that we owe the basic outline of the ‘castle story’.

It should of course be noted that their conclusions were necessarily a reflection of, and conditioned by, the time in which they wrote. Britain’s imperial position and global power were immense sources of pride and unusually, in British history, the armed forces were revered. Additionally, these early castle scholars were part of a general revival in interest in the Middle Ages that took place at the end of the nineteenth century. The military character they ascribed to the castle was a natural outcome of the Victorian view of British history, warfare and colonialism.7 On the eve of the First World War, the military interpretation of castles was firmly in place and the central tenets of this theory would change remarkably little over subsequent decades.

FIGURE 4. Tattershall Castle, Lincolnshire. The restored tower was built by Ralph Lord Cromwell around 1440 and is one of the finest brick-built structures of the fifteenth century. Note the windows.

JEAN WILLIAMSON

Towards an orthodoxy

The inter-war and immediate post-war periods saw the further development of this military interpretation of castles. Monographs by Oman (1926), Braun (1936) and Toy (1953, 1955), while all contributing new insights, essentially reinforced the conclusions of an earlier generation.8 In the aftermath of the two most destructive conflicts Europe had ever seen, there was little reason to question the influence that the matériel of war could have on society.

The decades after 1945 were dominated by the work of three scholars – A. Taylor, R. Allen Brown and D. J. Cathcart King. In the work of the latter two figures, the military interpretation of castles was, arguably, taken to its logical conclusion. The period after the Second World War was a time when new research produced significant quantities of information about castles: the publication of the medieval volumes of the History of the King’s Works marked a watershed in terms of information on royal castle-building and Taylor and Brown both published ground-breaking work on patterns of royal castlebuilding in England and Wales.9 At around the same time D. Renn published his study of Norman castles, which provided valuable new information on castles of the earlier period.10 An enormous amount of documentary research and fieldwork allowed King to publish, in 1984, his massive Castellarium Anglicanum, an inventory of castle sites in England and Wales; and, later, The Castle: An Interpretative History (1988).11 That the military role of the castle was ‘basically the most important’ was also evidenced by wider studies of medieval warfare.12 In 1956 John Beeler put forward the idea that castlebuilding during the reign of William I owed much to the king’s need to create a strategic ‘grand plan’ of castles in order to prevent insurrection.13

In terms of their ideas on the function of castles, Brown and King in particular closely allied themselves to the basic tenets first formulated by Armitage and Thompson. Brown’s best-known work, English Medieval Castles (1954, 1962, published as English Castles in the 3rd edition, 1976) leaves no doubt as to the military rationale that he believed governed castle development. A castle was ‘a fortified residence of a lord’ and despite the fact that new archaeological work necessitated the re-writing of earlier chapters for the third edition, he stuck closely to the idea that the castle was both feudal and military and had come to England at the time of the Conquest.14 The chapter titles of English Medieval Castles adhered to the familiar interpretation: the development of keeps is described in a chapter entitled ‘The Perfected Castle’, that for the Edwardian castles of North Wales is entitled ‘Apogee’, but hereafter the castle goes into ‘Decline’. The extended introduction to King’s Castellarium Anglicanum perhaps owed more to the work of Armitage, in that it deals substantially with issues such as siting and distribution, but again the military character of castles as private fortresses was not in doubt.15

This is not to say that the residential functions of castles were unappreciated or ignored at this time. Particularly innovative in the 1950s and 1960s was the work of P. Faulkner, who analysed castles in terms of their internal domestic arrangements and tried to relate the design of castles to their residential purpose.16 It is also worth noting that even some of the greatest exponents of the military school were puzzled by the seeming weaknesses of even some of the most famous castles. King speculated over sites such as Portchester, where a Norman keep stands in the corner of a Roman shore fort. The Roman structure exhibited the militarily-advantageous rounded towers that allowed flanking fire, but the Norman architects ignored this design and chose to build in an ‘inferior’ square style. Equally, the open-backed mural towers at castles such as Dover and Framlingham seemed entirely at odds with the careful design of the outward-facing arrow loops. King concluded that siege warfare must have been in its infancy at this time if builders could apparently disregard such obvious weaknesses.17 R. Allen Brown was also troubled by the fact that much of his own documentary research revealed that the majority of castles spent most of their time at peace and were often badly prepared for war on the few occasions that they did find themselves caught up in conflict. His conclusion was that castles were static defences that controlled the countryside and therefore did not need strong garrisons.18 Importantly, it was the puzzles that presented themselves at this time that would ultimately be responsible for the change in a...