![]()

![]()

DREAMERS

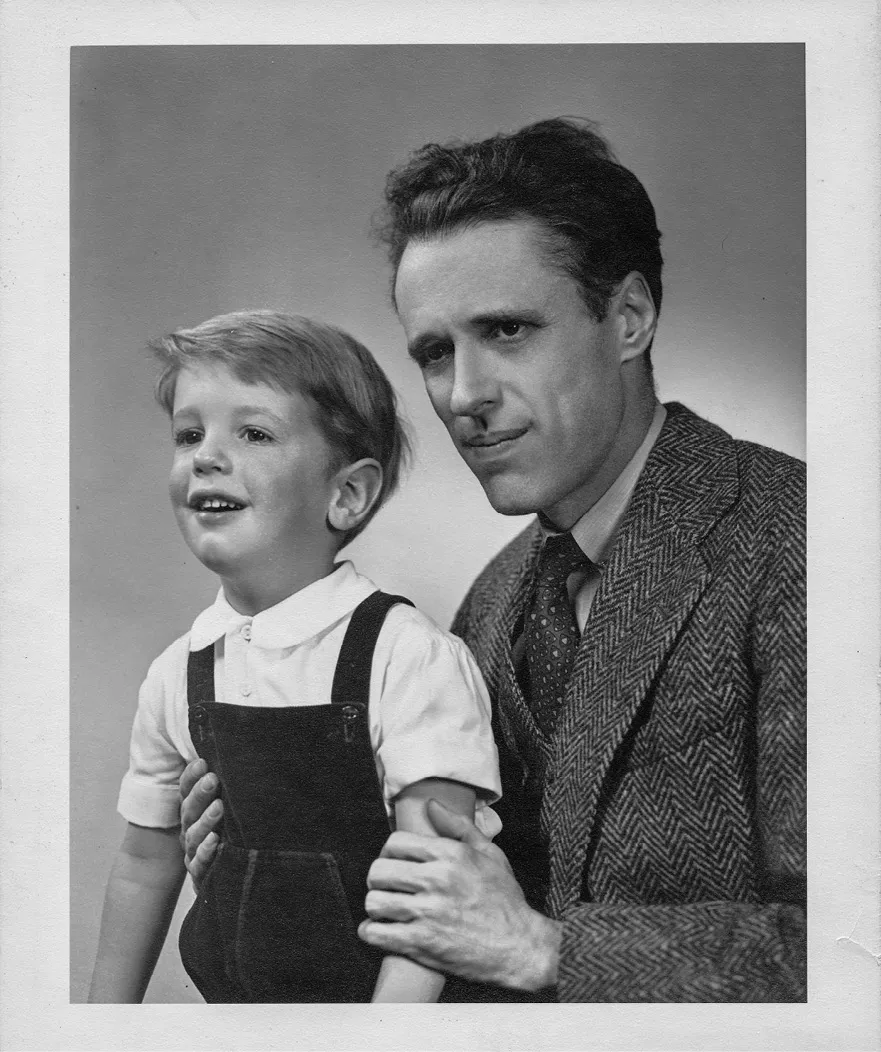

John

IT BEGINS LIKE THIS. A young man, born into privilege, his life a steady ascent from the town houses of Georgetown to the halls of Harvard, every door open to him, his family a bastion of the East Coast establishment. His father is the director of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, a mentor to Jackie Kennedy, and a regular visitor at the White House. The family’s social circle—Isaiah Berlin, Dylan Thomas, T. S. Eliot, Paul Mellon, Joe Alsop—unlocking worlds and opportunities.

Cocktail parties with crystal chandeliers and monogrammed silverware. Weekends in Dumbarton Oaks, an elegant estate at the highest point of Georgetown, where his father is on the board. Swimming in the marble-edged pool, Schubert concerts at night, tea under the loggia, playing hide-and-seek with his sister, Gillian, amid the wisteria and fountains in the Italian gardens.

Summers crossing the Atlantic, to his mother’s childhood home in England, and an ancestral castle in Scotland. First class on the Queen Mary, John and Gillian excited kids, running around, exploring the boiler room and lower levels. The war has just ended and sometimes they see troops on the ships, in hammocks strung across decks. Once they bump into Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers; of course they ask for autographs.

John Anthony Drummond Walker, born June 30, 1942. He is tall (six feet two inches) and angular, with a long, pensive face, handsome in a reticent, unreachable way. Everyone says he has his father’s easy charm; he leads a gilded life. And yet: He has always felt a twinge of dissatisfaction, a constant if barely articulated restlessness, like an itch. It will propel him from place to place, quest to quest, cause to cause. Always searching, always moving—never, it seems, quite arriving.

His father, John Walker III, is a man of substance, part of a Georgetown clique that dominates political and cultural life in the capital in the postwar years. He is the first curator of the National Gallery, joining the institution when it is founded in 1937, and soon he is its director. He walks with a limp from a childhood case of polio, but he is handsome and imposing, and through charisma, connections, and persistence, he builds the fledgling gallery into one of the preeminent cultural organizations of the world. He comes from old Pittsburgh money—his grandfather was part of a circle of wealthy Scotch industrialists, a partner to Andrew Carnegie—and travels in rich, cultured circles. This helps Walker Sr. acquire for the gallery, and for the country, a string of notable artists: Cézanne, da Vinci, Picasso, Rembrandt, Titian, Raphael, van Gogh.

John’s mother, Lady Margaret Drummond, is the daughter of Sir Eric Drummond—the sixteenth Earl of Perth, the first secretary-general of the League of Nations, later the British ambassador to Rome. They are lineal descendants from Mary, Queen of Scots, and two Catholic saints and martyrs, including Thomas More, the patron saint of utopia. Her marriage to Walker Sr., held at St. Andrew’s church in Rome, is the subject of international newspaper headlines; the pope sends a telegram with benedictions.

John grows up with tales of his family’s esteemed lineage. He carries these tales with him wherever he goes, ambivalently and often grudgingly, a pedigree to live up to. As a child, he reads his mother’s gold-edged copy of A Book of English Martyrs, which includes sections on his ancestors. “Not disloyalty, not treason, but conscience was their true offence,” proclaims the preface. John is taught that his forefathers ended up in the Tower of London for their Catholic convictions. When push comes to shove, he is told, one must be ready to die for one’s beliefs. Perhaps this offers some insight into what comes later.

A rich, privileged life; and a fun life, too. While there will always be a certain austerity to John, an element of renunciation and self-abnegation, he is a man of multitudes, and he also contains a strong streak of hedonism. He parties at Harvard, dancing on tables at the Casablanca, a bohemian hangout, and sipping daiquiris and cheap Italian wine (Orvieto white, $1.20 a bottle) while talking literature at the Harvard Advocate. He belongs to a circle of off-campus rich kids that drink and smoke with glamorous women and men (it’s a very gay scene, ahead of its time). The socialite Edie Sedgwick—one of Andy Warhol’s Superstars, an icon of the sixties—is a close friend, and a regular at their parties. John drinks with classmates on the top floor of the A.D., a student club, and they rain glasses on passersby below. Later, the police will make them get on their knees and clean the brick sidewalk with toothbrushes.

The prince of Lichtenstein visits Cambridge while John is at Harvard. The prince’s father has a formidable art collection. It includes Leonardo da Vinci’s Ginevra de’ Benci, one of the only Leonardos in the world still in a private collection. John’s father is eager to get his hands on the painting; a self-respecting national gallery must have a Leonardo. He has heard that the royal family might be amenable to selling, and he seeks to cultivate the young prince (“Baby Lichtenstein,” he calls him). He asks John to meet the prince in Cambridge and opens an expense account for his son at the Club Henry IV, an upscale French restaurant in Harvard Square. John takes maximum advantage, racking up bills on escargots, coq au vin, steak, and imported wine. One lunch with the prince amounts to $124; his father is flummoxed, but all is later forgiven when the Ginevra is acquired—at a rumored price of more than $5 million, the highest ever paid for a painting—making it the only Leonardo in the Americas.

Around the same time, John’s father presides over a courtly evening at the National Gallery, attended, among others, by President Kennedy, Vice President Johnson, their wives, Secretary of State Dean Rusk, and nearly every member of Congress. Walker Sr. has worked for months in partnership with Jackie Kennedy and André Malraux, the French minister of culture, to set up an American viewing of the Mona Lisa. The four-century-old painting has been transported in its own ship cabin across the Atlantic, and Walker Sr. unveils it in a columned rotunda on the second floor of the Gallery. The ceremony cements his position at the heart of Washington’s power structure.

John is going in a different direction. He attends a lecture at MIT by Aldous Huxley, the English author and philosopher who has just published his utopian novel, Island, in which psychedelics and Eastern mysticism combine to create an ideal society. John listens to Huxley, and something in him stirs. Shortly afterward, he gets mixed up in the Timothy Leary–Richard Alpert drug experiments at Harvard and takes LSD for the first time. The stirring becomes a shaking. John’s world—that safe, establishment cocoon of his father’s—loses its foundations. He is depressed and aimless; his sister visits him in Cambridge and finds his apartment disordered, its condition, she feels, reflecting John’s state of mind.

The first in a series of dropouts and incomplete assignments in life ensues. He takes time off from college and heads to Portsmouth Abbey, a Catholic Benedictine monastery and boarding school in Rhode Island, where he was a student before Harvard. He spends a year in retreat, meditating and wandering the expansive campus that slopes into Narragansett Bay, attending prayers in the vaulting wooden cathedral. He is searching, seeking new horizons; and so, during the same period, is American Catholicism, which is opening itself to Eastern religion. John discovers Buddhism, he reads Thomas Merton, and grows close to Aelred Graham, a member of the Portsmouth community. He helps Graham build a Zen garden outside the monastery. Every morning, Graham takes his clothes off in a ground-floor, glass-fronted room and performs elaborate yoga poses. One time the cleaning man walks in and finds an undressed Graham in a headstand. “Well, he seems to see the world upside down,” the cleaner later remarks. He’s onto something: it’s the early sixties, and soon everything will be upside down.

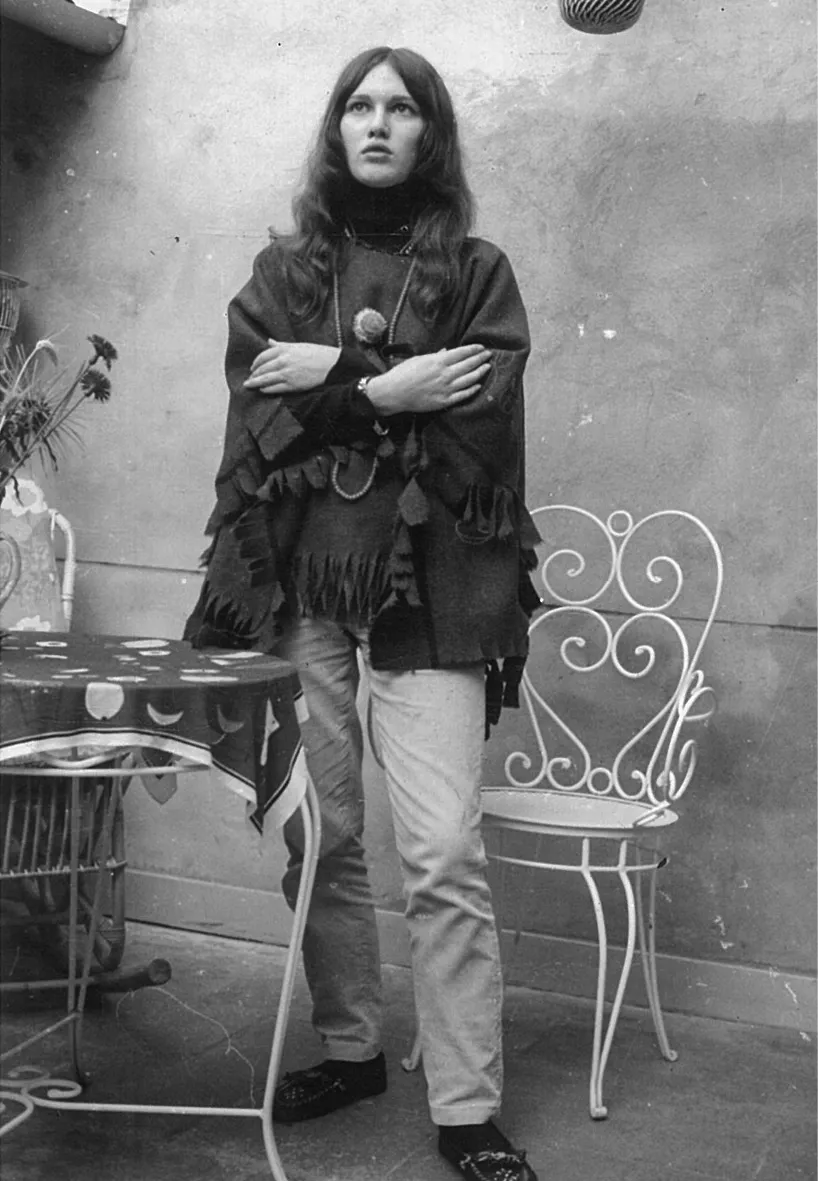

Diane

In Belgium, in the town of Sint-Niklaas, a warren of winding streets and attached homes, a baby girl, Diane Maes, is born on May 23, 1950. She will grow into a vibrant, vivacious woman, and she, too, will feel a constant restlessness. But Diane’s restlessness is less vague. There is no ambivalence in her; she is blessed with clarity and single-mindedness, a gift of faith that will long elude John. Diane knows what she wants. She wants to escape her town, get away from its provinciality and the clutches of her controlling mother.

Small-town life in East Flanders is idyllic, or deadly boring—it depends on your perspective. Farmers’ markets on weekends in the town square, the largest in Belgium. A few steps away, a green park and a castle, with a wide moat. Like most families in the region, hers is devoutly Catholic. Every Sunday they attend the Church of Our Lady, with its colorful murals and towering gold statue. One time when Diane is fourteen, she visits a local country market and enters a dance contest. She’s on a wooden stage, laughing, loud music playing, and she does the twist; she wins a prize, a lamp. Happy days. She’s slightly built with high cheekbones and cherry lips that open up to straight white teeth, and a girlish, joyful giggle. She has dreamy gray-blue eyes, and a habit of punctuating her sentences with “Weet ge? Weet ge?” (You know? You know?) Sometimes she puts her arm on people’s shoulders when she says that, leans in to them. Men melt; Diane is magnetic.

Her father is a housepainter. He spends much of his time on the road, at construction sites across the country. He is a big, popular man, nicknamed Tarzan. One day he visits an astrologer. When he returns home, he tells his family, “Look at me, I am a man as strong as a tree but I won’t live long.” As his wife turns toward him, he seems to vanish. That night in bed she touches her husband and his body is cold. Soon after, he travels for a job. His wife gives him money for a train ticket and tells him to be careful. He drinks and gambles the money away, and a friend offers him a ride home. Maybe the friend also has been drinking. A train hits their car at a crossing and Diane’s father is killed. One of his eyes falls out; it is later found on the floor of the car.

Life gets harder for the family. Diane, her sister, and their mother must now rely on government welfare money, monthly checks that are conditional on the girls continuing their educations. Diane enrolls in an arts institute in Antwerp. She’s an indifferent student, bored and distracted. She meets a man. He’s five years older, tall and good-looking, with a long beard and flowing brown hair. He’s a hippie. He has traveled overland to India, Turkey, Afghanistan. He’s written about it in a local newspaper; he tells such stories! Diane wants to run away with him but her mother steps in. Diane is just sixteen, and besides, the family needs the government checks that arrive for her education.

Diane’s mother puts her in a Catholic reform school, and her world constricts further. She feels trapped by the rules, the formality, and the hierarchy. She will harbor a lifelong suspicion, terror even, of institutions, and she comes to abhor organized religion. One day she steals the flowers from church. Her family is aghast. Later, they will wonder if this was the reason for all her troubles.

Bernard

In Paris, on a snowy October 30, 1923, a boy is born. Bernard Enginger is the son of Maurice, a chemical engineer, and Marie-Louise, a housewife. Bernard is the second of eight children. He spends his young years between Paris and Saint-Pierre-Quiberon, the family’s ancestral village in Brittany. He, too, feels constrained by the smallness of his world: the pettiness of commerce and religion, the strictures of bourgeois propriety. He is happiest in the summers, when the family vacations in Brittany and he can sail alone on the Atlantic. Out on the waters, Bernard is free. As soon as he returns to land, he feels imprisoned. Even as a boy, he is possessed by doubts and questions, a sense of existential vacancy.

He is strong-willed and a little wild. As a child, he sets fire to a closet at home. One night he cuts the electrical wires with a pair of scissors and plunges the family into darkness. He butts heads with his father, who accuses Bernard of having no religion. When the Nazis invade France, Bernard is determined to join the French Resistance; his father warns him that he will be expelled from the family. Undissuaded, Bernard joins Turma-Vengeance, one of the largest and most active wings of the Resistance. He surveys military installations on the Atlantic coast, carries messages between cells, and transports weapons and explosives.

One day Bernard is sent on a mission to Bordeaux. A spy has infiltrated Turma-Vengeance and he must warn his colleagues. But he is betrayed by another spy—they are everywhere, these spies: this will feed a lifelong suspiciousness—and, on Boulevard Pasteur, in Bordeaux, a black car from the Kriminalpolizei screeches to a halt, two men with pistols jump out, and they arrest him. Bernard spends the next several months being moved from prison to prison, often in solitary confinement, interrogated and brutally tortured by the Gestapo. Later, he will say that his life begins only when he is tortured; it is his first real moment of existence.

The Nazis plunge Bernard’s head into a sink of water, and they almost drown him. They do other things, too, gruesome things about which he will never be able to speak. But Bernard remains unbroken. The Nazis call his parents in; they warn the father that unless he gets his son to talk, Bernard will be executed. The father asks Bernard’s torturers if they would try to convince their own children to betray their companions. Bernard is put on a train for the concentration camp of Buchenwald, and from there he’s sent to Mauthausen, in Austria. Mauthausen has a reputation as one of the toughest concentration camps. Bernard works in the granite quarries; half his fellow prisoners die.

After liberation, Bernard makes his way back to the family home, in the sixth arrondissement of Paris. His mother’s hair has turned white during his absence. He is barely recovered from typhus, and he weighs just fifty-five pounds. Europe rebuilds, France begins unpicking the tangle of defeat and collaboration. Life goes on—but not for Bernard. For him, the period after liberation is worse than the camps themselves. Everything is broken; he feels hollow, and he contemplates suicide. Finally, a cousin who has been appointed the governor of Pondicherry, a French colony in South India, steps in and offers him a job as his secretary. Bernard leaps at the opportunity: a chance to get away, to start anew.

On the way to Pondicherry, he stops in Egypt and, in a hotel in Luxor, bumps into the French writer André Gide. Bernard has long admired Gide’s work; he credits it with keeping him alive in the concentration camps. He writes Gide a letter, saying, “J’ai soif. Tous les jeunes ont soif avec moi” (I am thirsty. All the young people share my thirst). To Bernard’s surprise and joy, Gide replies. He writes that he sympathizes with Bernard’s impatience; he advises him to avoid all ideologies and institutions, to resist the temptations of religion and isms. He adds, “Le monde ne sera sauvé, s’il peut l’être, que par des insoumis” (The world will be saved, if it can be, only by rebels).

J’ai soif. All these dreamers, all these searchers. John, Diane, Bernard: all rebels in their own way, each trying to fill a distinctive gap in their soul, each looking in a different place. Who can foretell how their lives will intersect? Who can predict that they will meet on the same arid patch of earth in India? They will be joined by hundreds and then thousands of others. So many around the world are propelled by the same thirst, the same vague longing for something different, something more meaningful—a deeper way of living.

Where does this urge come from? You could say it’s the human condition. We all want better, we’re all always imagining fresh starts and alternative lives. Everyone is at heart a utopian. But maybe it’s easier to follow our dreams at certain times than at others. There’s something about the era in which these people are living. Some moments in time are simply more epochal: they offer more scaffolding for our ideals, and for our fantasies of reinvention.

Auroville will be founded in 1968. Really, though, it emerges from the rubble of the Second World War. In the wake of that nihilism, an...