eBook - ePub

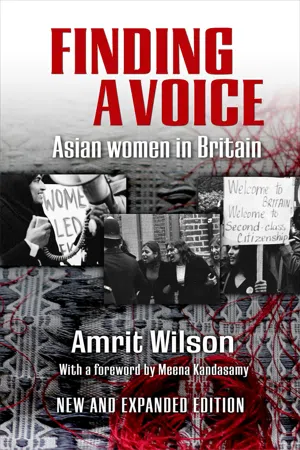

Finding a Voice: Asian Women in Britiain

Asian Women in Britain (New and Expanded Edition)

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Finding a Voice: Asian Women in Britiain

Asian Women in Britain (New and Expanded Edition)

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Finding a Voice: Asian Women in Britiain by Amrit Wilson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Feminism & Feminist Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

11

In conversation with Finding a Voice: 40 years on

The writings in this chapter are by women from the two generations after mine who read, or re-read, Finding a Voice forty years after it was written. These are not appreciations or critiques of the book but rather analytical reflections, trains of thought and stories of their lives and struggles woven around those in the book: conversations, as it were, with the original book grounded in contemporary Britain.

§

Camille Kumar

I didn’t speak for several years at school. Whatever the subject, teachers would always have some variation of this sentence in my annual report: ‘Camille has a lovely smile, but she is painfully shy’. I wasn’t unhappy, just silent. Finding a Voice is about breaking silence. About the liberation that is inherent in speaking your truth, as well as the action it spurs.

In my work in the ending Violence Against Women field, supporting women to speak their truth is the heart of our work. In supporting women to tell their stories, we listen for the story that sits between the words. When women tell us of the relentless abuse they have experienced at the hands of a man, we listen for the flashes of resistance and rebellion where their spirit lives. When she tells us of her weakness in having suffered too many times, we reflect back her strength at fiercely loving in the face of anger, her profound faith in believing that people can change, her courage at speaking out and refusing to be silenced. We take a mirror and reflect what we see until she sees it also.

In Finding a Voice, Amrit created a space for several generations of women to develop a language to tell their truths. By weaving the stories together through points of connection, difference and insightful reflections, the honour and complex humanity of the women story-tellers is recognised and explored.

It is so interesting how women tell their truths in the chapter Adolescence and Marriage. The young women are able to speak directly to the Asian reader, relying on a shared understanding of identity. Simultaneously, the young women are interpreting their truths for the non-Asian reader. The non-Asian reader who may not understand the tyranny of withheld affection, regimented home life and domestic servitude that gives oppression shape in the lives of some Asian women. The chapter provides space for those young women to tell their truths, and the stories become moments of release. Once the words are spoken, there is no possibility to move forward on the same path, it forces the hand of both the story-teller and the reader. This process, of having your path altered by the act of speaking your truth, resonated strongly for me and my own experience of coming out to my family. Once spoken, I was not able to unsay what I had said. And my mother was not able to un-hear it.

As the young women reflect on their and other women’s experiences of family, they tease at the unravelling threads, revealing how internalised misogyny and compulsory heterosexuality are endemic in both the host and migrant community. With this so clearly laid out on these pages, the queer reader finds herself visible through her invisibility. The lesbian reader dreams queerness into the complex lives of the story tellers, imagining the stolen moments of intimacy the story-tellers may have shared with other women, or the forbidden fantasies they are yet to give voice to. But I wonder whether the straight reader sees this also.

For me there is something so familiar yet so distant in what the young women speak of. Of the rules and rule breaking in women’s lives lived in captivity and the cruelty that ensues. Of the conditional love not speaking your truth affords you access to. Of the complicated freedom that speaking your truth can open up. As Amrit captures, ‘To break out of the family’s arm lock, you also have to cast off its embrace.’

Intergenerational guilt, fear, shame, pride, judgement, aspiration, detachment, confusion, agency, naivety, conditional love, pain, rules and constraint. These themes are so consistent across all the young women’s stories, as they have been in mine as the lesbian daughter of strict Hindu parents. I feel a connection to my straight sisters in reading their thoughts. A moving experience for those of us who are no longer able to speak to our sisters because of self or family-imposed queer exile.

It can be so challenging to write about your own community. Scarred by anthropologists dehumanising gaze, many authors of colour are unable to break from the tradition of false objectivity. White feminists and anthropologists typify the experiences of South Asian women as that of a unique and extreme subjugation, the ‘barbaric Asian male’ with his exoticized tools of oppression being implicit in this characterisation. The inaccurately racialised reporting of child sexual exploitation in the UK over the last ten years is an example of this homogenising stereotyping. Amrit resists this tradition, taking a Black Feminist approach of deliberate subjectivity, intimate reflections and direct story-telling.

Adolescence and Marriage captures the specificity of the experiences of second, third and fourth generation British Asian women who are not just dealing with the ‘generation gap’, but also the racism of the host community and the embedding of fixed traditions that migration provokes. Rather than focusing on the migrants as the peculiar subject, Amrit pulls out the connections, differences, flaws and fractures in both the host and the migrant communities. This is so liberating to read as an Asian woman. It enables you to engage with painful realities of your own life without losing agency, to engage with the ugliness of your own community without being self-hating and to celebrate those generations of Asian women who have resisted before you. It is a reminder that, as Angela Davis says, we are living the imaginations of our grandmother’s grandmothers.

This chapter holds up a mirror to the reader also. Amrit writes, ‘Reputation is a tremendous conservative force, controlling, to differing extents, everyone in Asian societies.’ The young women’s reflections on Izzat made me think of my own position in British Asian society. When I first meet people, they often don’t know where I am from. I have always found this confusing because I have strong Indian physical features. I suppose there are many reasons for this lack of recognition, but part of me will always feel that I am unrecognisable because I am not with my family. Because without my family, I have no Izzat and without Izzat I am not recognisable. Where does a Fiji-Indian-Australian lesbian living in England with her white British wife, engaged in feminist struggle and anti-violence work, fit into the hierarchy of Khandan and Izzat? My triple crossing of the kala pani, the perceived double crossing of my family in being a lesbian has, to some extent, cut me adrift from all of it. When I read Manjula’s story I am struck by the similarities of our experiences: The withdrawn affection, the closing of our worlds, the constriction of our beings, the atmosphere of guilt and disappointment. Yet I also feel far from her. I wonder what Manjula would think of my Izzat if she met me.

What does Izzat mean for Asian lesbians and our queer sisters? If going out with boys is risky and wicked, what words are there for the girls who go out with girls? At what point was my reputation unsalvageable? Reading the stories of the young girls tell of their adventures with boys, I am reminded of my own fall from grace for the opposite reason. And the unending consequences this has had on my relationship with my family and theirs with everyone they know. I stepped out of Asian society in that way, but my parents still live there. As I write I still must carefully consider how much I share of my story because of my mother’s honour.

We were one of the first families in my extended family to move to Australia from Fiji Islands. My two brothers and I were raised in white Australia by aspirational parents. We were the only Asian family in our neighbourhood and my father’s aspirations were for a middle-class life. At that time, a middle-class life in Sydney meant a white life and so his aspirations for class became tightly bound with race aspirations. My father didn’t want us to have accents or eat with our hands.

My parents spent many years immigration sponsoring family members to move from Fiji Islands to Australia. By the time I was a teenager, I had dozens of cousins who had moved to Sydney from Fiji Islands and we increasingly socialised with them. My mother thought my female cousins were perfect Indian daughters, speaking fluent Hindi, rolling perfectly round rotis and uncomplainingly wearing the shapeless, gaudy salwar suits they had brought over from Fiji, nothing like the tailored salwar suits worn by ‘Indian Indians’ or the tight t-shirts and jeans I had taken to wearing.

My cousins were so different to my brothers and I. We were not good Indian children. We spoke our minds, we did not talk about marriage and I could not roll roti. As we socialised more with our ever-growing family, the differences between us and our cousins became sharper. I can still feel the hot flush of embarrassment on my face as an Aunt would say something in Hindi to me that I could not understand, or when another Aunt asked me to prepare the dough for puri and I inevitably did it wrong. Worse than my own shame was that of my parents. I felt my parents’ shame and embarrassment of my brothers and I and started begging not to have to go to what had become for me stressful family events.

In fact, my cousins were not ‘good girls’, and they were doing a lot of the things the young women in this chapter speak of. As Nirmal describes in the chapter, ‘Apart from anything else, you are two people you see. In front of your parents you are different and outside you are different … So I have two faces.’ My cousins were constantly balancing on a tightrope of lies and compromises between two worlds, sometimes faltering, sometimes running. I never learnt how to do that, I never understood it. Perhaps my fierce lesbian heart sensed this would not work for me, and so I never tried. I remember one day my mother came to learn that one of my perfect girl cousins had a boyfriend. I remember how shocked my mother was. She told me she respected my honesty, that I wasn’t living a ‘double-life’. It was a rare moment of seeing each other clearly.

In the chapter, Nirmal shares more about this double life and explains it is the family face she would keep for her husband. It makes me want to ask her, who gets to see the other face? What happens to her? Is she put into a closet in your mind, forever screaming inside? Or is she allowed out in the secret domestic world of women, which is often the space reserved for intimacy, friendship and love in an Asian woman’s life. A space so beautifully explored in other chapters of the book.

§

Jannat Hossain

Finding a Voice came to me as the seventieth anniversary of partition loomed, and as I rushed to learn as much as I could about the history of present-day South Asia. Reading the book, I learned more about the early history of South Asians in Britain, something often forgotten by many second and third generation British Asians, myself included.

It helped me to further understand and resolve the racism I internalised while growing up. It explained some of the injustices I had felt in our communities, but instead of asking why, had looked internally for blame. When my parents didn’t have enough money to buy us everything we needed at the start of the school year, I was angry at them and not the system that stopped them from earning enough for these essentials. When I spent hours with friends experimenting how we could be ‘beautiful’ (‘keep using those skin lightening creams, it’s working!’ and ‘you should wear a peg on your nose when you sleep, so it’ll be pointier, it worked for my sister’), I lived for what felt like the joy of it all, not stopping to think where our ideas of beauty came from and not aware of the appallingly low self-esteem, unnecessary suffering and self-harm it was causing.

Of all the books I’ve read in my adult life, it’s the book I’d gift my younger self.

*

London; it has the ache of home. It’s the city I was born in and it’s the city I’ll most likely die in. Growing up here, I had always felt comfortable and safe—racism was largely unheard of in my community of mainly people of colour in East London, in the sheltered upbringing my parents chose for us. But now parts of London are places I no longer recognise and often feel like I no longer belong in.

I know racism has always existed in Britain, the country’s foundations rest on it but I had believed a lot of the racism of my parents’ generation had been relegated to the dustbin of history. This has changed massively for me as the years have gone by. I am no longer a seventeen-year-old still living in a safe bubble but a twenty-seven-year-old dreaming of living in a different world, because in the last ten years or so the increase in state and street racism has been hard to avoid hearing about, witnessing and living almost every day.

Leaving university and entering the workplace has many challenges but for people of colour it brings with it a new racism, one that’s so ingrained in our workplaces that no amount of ‘diversity and inclusion’ talk can make a difference. Whether it’s getting to interview stage, getting the same opportunities as our white colleagues or getting an adequate response when we talk about racism, employers are reluctant to address the structural issues blocking people of colour at every step.

On top of this when we look for a place to live, we are met with hostile landlords and potential housemates who are either put off by our names or if we pass that barrier, by our skin colour upon first meeting us. Their fear is for trivial but racist reasons, based on stereotypes such as their home smelling of curry should they let us move in, similar to what is described in Finding a Voice—simply a more covert form of racism than the ‘No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs’ signs landlords used to keep our parents away.

Gentrification has now all but destroyed the soul of this city with the people of colour who built it facing the brunt of its impact. One of the women in Finding a Voice, Zubeida, talks about Scala (former cinema, now famous nightclub) and how it was one of the highlights of the week for her—she visited it every Saturday to watch films with her husband—something that gave her respite from the loneliness she felt. It’s a story that has stayed with me. I work in King’s Cross and walk past Scala several times a week and every time I think of Zubeida, the life she may have gone on to have, the life she might have now. Scala now just serves as a reminder of gentrification in the area, a hub for the middle classes. As I walk around the area surrounding Scala, I think about the pockets of social housing and small Bangladeshi grocers and corner shops that still stand and wonder whether they will be around for much longer. In 2013 Camden Council, the local authority responsible for the area, responded to government cuts by moving hundreds of poor families out of the area and rehousing them in towns and cities like Bradford, several hundreds of miles away. There too, these internal refugees, displaced from the roots they had laid down, are not welcome.

These are the same streets where our black and brown bodies are subject to physical and mental harm—from being abused for the colour of our skin to being attacked because of the religion we choose to follow and practice. Just a few days before I started writing this piece, on my way home from work, on my own street, as I walked passed some white kids, I had to listen to a girl of about 16 say to her friend, a boy of similar age who lived on the street, that she didn’t understand why they couldn’t attack Muslims when they were being attacked by Muslims. The boy held in his hand an axe. I thought of these kids and their presence in our community. I thought of my parents who supported their families when they moved in; from giving them old furniture to supporting their father with odd jobs. I wondered how we went from being on good terms to being what in that moment felt like enemies. I wondered how we got here, is this how the growing fascism worldwide is going to play out in our communities? The brainwashing of these kids by the mainstream media and no doubt the influences in their lives, remind me of how white supremacy marginalises people of colour with its inherent structural racism, then turns around and demonises us as aggressors and plays the victim. Contrary to what some of this country’s leaders would have us believe there is no freedom to walk the streets of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Praise for Finding a Voice

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Table Of Contents

- Foreword

- Reclaiming our collective past as an act of resistance

- Acknowledgements

- Areas from which South Asian immigrants came to Britain

- The Prisoner

- Introduction to the first edition

- Isolation

- The Family

- Work Outside the Home

- Immigration

- School Life

- Adolescence and Marriage

- Sisters in Struggle

- Reflections

- In conversation with Finding a Voice: 40 years on

- Some moments to remember

- Index