![]()

PART I

Renaissance and Enlightenment

![]()

1

AGENTS AND MERCHANTS:

Dealing before 1700

Where should a history of art dealing begin? The original template for the acquisition of a work of art was for an artist to paint a picture that he then sold to a person who liked it enough to want to hang it on his wall, or for the owner of a work that had already changed hands to find a buyer for it in exchange for an acceptable price. It was a one-to-one transaction. Sometimes rich men—patrons—would commission paintings from artists, but again they would go direct to them. The process changes when the seller of a work of art—be he its creator or its current owner—concludes that the price he is going to achieve will be higher in the hands of an expert third party mediating between seller and buyer than by relying on his own efforts. This is the moment when the vague form of the art dealer—wielding his timeless attributes of charm, cunning and expertise—emerges from the primeval gloom.

The poet Horace attests that a trade in Ancient Greek statuary was conducted by collectors turned dealers in Imperial Rome. According to the historian Pliny, paintings by the artists of antiquity were similarly bought and sold. Pliny, who had a scientifically inquiring mind, grapples with the question of how prices for works of art are established. He recognizes that the identity and the reputation of the artist is one factor, and subject matter is another: He gives an interesting account of how demand for scenes of everyday life increased in Imperial Rome, in preference to more traditional scenes of a grander nature involving gods and military triumphs. Here is a precedent for the bourgeois taste for genre painting that emerged in seventeenth-century Holland. But uncertainty over correct pricing persists, and Pliny also tells us that, when all other criteria for mutual agreement between buyer and seller failed, paintings were sometimes priced by weight. A similar system in the present day would presumably make Frank Auerbach, with his thickly trowelled-on impasto, the most expensive painter in the world. But the fact that such a measurement was sometimes resorted to in Rome indicates that the power of the dealer was still limited. If the only specialist knowledge required to trade in art is a pair of weighing scales, then the operation is no different from dealing in potatoes. But to the extent that successful dealing also involves expertise in artists’ identities and understanding of what makes desirable subject matter, then the role of the art dealer takes on greater significance.

The Dark Ages intervene, but the art trade regathers momentum in the fifteenth century. In pre-Renaissance times the main function of Western Art was as the visual arm of the Christian religion. Most paintings were directly commissioned from artists by Church authorities or by rich donors anxious to please the Church. But with the early Renaissance, new lines of more commercial subject matter emerge alongside depictions of saints, crucifixions and holy families: mythological scenes, portraits, even some landscapes. The early art market was exactly that: a physical marketplace, where stallholders gathered on prearranged days through the year to offer works of art for sale. The first examples of these markets sprang up in Flanders, the great center of European trade.

There were guilds and corporations regulating the production of and commerce in many things by this time. Paintings were no exception. The regulations of the Bruges Corporation of Image Makers of 1466 laid down that a merchant could only sell art “in his inn at opening hours except on the three exhibition days during the Bruges year market, and the panels have to be of good quality, and this will be approved and expressed by the dean and the inspectors on their oath.” The dean and the inspectors on their oath sound ominously familiar: They are the direct ancestors of the vetting committees at international art fairs five and a half centuries later. No doubt they met with similarly aggrieved reaction from exhibitors falling foul of quality control.

In 1460, a covered market, or “Pand,” began operation in the grounds of the church of Our Lady in Antwerp expressly for the sale of works of art. Stalls were rented to individuals for use during the biannual trade fairs. These stallholders were generally artists selling their own paintings, but gradually some took on the selling of the work of other (possibly less persuasive) artists. In so doing they were carving out for themselves the role of art dealers. The buyers were generally merchants, often buying paintings for export and resale in other countries—here were the first international art dealers. Or they were agents; the Medici, for instance, sent their representatives to Antwerp to buy paintings and tapestries, which they then shipped to Florence packed between bales of wool. By the 1540s the Pand had been subsumed into the Antwerp Exchange, an enterprise in which bankers, merchants and art dealers were brought together under the same roof to facilitate all sorts of transactions. Business boomed. It was a reflection of Antwerp’s position as one of the great European trade centers, a place where people from all over Europe came to buy and sell. Daniel Rogers, an English envoy, recorded in wonder that the Antwerp Exchange was “a small world wherein all parts of the great world are united,” an early instance of globalization. Art was a commodity like the others being traded in the same premises. In 1553 more than four tons of paintings and 70,000 yards of tapestries were shipped from Antwerp to Spain and Portugal. Art, when aesthetic criteria became commercially confusing, was still in the last resort being priced by weight.

But it was in the seventeenth century that the art market moved up a further gear, given impetus by dealers becoming increasingly international, and thus leveraging the price differential for individual works of art from country to country. In Amsterdam Hendrick van Uylenburgh, who effectively became Rembrandt’s dealer by employing him in the Uylenburgh workshop in the 1630s, over time established a web of international agents with whom he did business: Peter Lely in London, Everhard Jabach in Paris and Jürgen Ovens in Schleswig-Holstein. Jean-Michel Picart (1600–1682) was an art dealer in Paris who entered into a commercial arrangement with Matthijs Musson (1598–c.1679) in Antwerp. Musson provided Picart with works painted in Antwerp to sell on the Paris market. Picart conveyed to Musson the ins and outs of Parisian taste, and Musson organized artists in Antwerp to paint pictures that met it. Correspondence between them survives. What did Picart (and therefore Paris) want? Church interiors; allegorical pieces such as The Five Senses; scenes of peasants and animals. Musson supplied him with a pair of hunting scenes by Frans Snyders for which he had high hopes, but ended up only making a profit of 9 percent on them, or so he told Musson. As ever, the challenge was speed of communication. Letters took seven days to reach Paris from Antwerp, and vice versa. A lot can happen in seven days, and each side suspected the other of deceiving them. Another Parisian dealer supplied by Musson was Nicolas Perruchot, who wrote him letters further deepening his understanding of Parisian taste. “As for the paintings of Francesco Albani, they are esteemed in Paris, as long as they are not his latest ones,” Perruchot advised him. Such art market intelligence is always crucial. Its exchange helps keep dealers ahead of the game.

The pattern of Antwerp as a major source of supply of art to other European centers of consumption was reinforced by Melchior Forchondt, together with his son Guillam and various grandsons. As a family they fanned out across Europe, the Duveens of the seventeenth century, selling both mass-produced Flemish works and also older, more rarefied pictures. Three Forchondt offspring set up a branch in Vienna in the 1660s, which did well and enabled them to meet the growing demand in Germany as collectors recovered economically from the Thirty Years’ War. They also had branches in Paris, Lisbon and Cádiz, where—a couple of centuries too early—they staked an early claim to the inchoate transatlantic market for European art.

Almost all the names mentioned above as active in the European art trade in the seventeenth century were artists; many of them turned to dealing because they couldn’t make a living painting. There was a blurring of the distinction between the two activities, and artists were at an advantage as dealers because there was a wide presumption that only artists knew enough about art to be successful or reliable in purveying it. In 1619 the Guild of Painters and Sculptors in Paris tried to enshrine this presumption in law by adding articles to their statutes obliging bailiffs to obtain authorization of a master in order to sell paintings or sculptures.

At the top end of the art market, the advance of art dealing in the seventeenth century was also driven by dealers exploiting the growing perception that artists were more than the manufacturers of a product. The great masters of the Italian Renaissance set a standard of heroic excellence, which had a trickle-down effect and raised the status of all artists and the desirability of their creations. Paintings were increasingly marketed not just as luxury objects but as examples of one of the Liberal Arts. In their own time, the success of Leonardo, Raphael, Michelangelo and Titian had not been mediated by the efforts of dealers, because their work was commissioned directly by princes (royal, ecclesiastical or commercial). But in the generations that followed a myth about these artistic giants was established, encouraged by writers such as Giorgio Vasari, the first great art historian. This in turn led to rich collectors hunting their work like the rarest of big game. Here was the first trophy art, and embryonic dealers were on hand to purvey it, in the first instance as agents prepared to travel to source it, most productively to Italy itself.

That dealers were successful in Italy is attested by the outrage they provoked. There was seventeenth-century resistance to the trafficking of works by already-established and highly revered masters. The Accademia di San Luca thundered, “It is serious, lamentable and indeed intolerable to everybody to see works intended for the decoration of Sacred Temples or the splendor of noble palaces exhibited in shops or in streets like cheap goods for sale.” Clearly dealers were going to have to adapt, to present themselves as something more than mere traders in goods. At the root of the invention of art dealing in its modern form lies the Renaissance-era transmutation of the painting, the object to be sold, from manual craft to Liberal Art. This made new demands on dealers and opened up new opportunities for them. What emerged—alongside the more traditional dealer who might ply his trade from a shop or an artist’s workshop—was a new sort of dealer, operating in that no man’s land where the amateur shades into the territory of the merchant—the collector who assembles beautiful works in his house or gallery, and occasionally allows himself to be separated from them, generally at a substantial profit. What he is offering is a combination of social acceptability and expertise. He presents what he is dealing in not as merchandise but as something more rarefied. As a way forward it has its merits. You can ask a higher price for an example of the Liberal Arts into which you have a superior understanding than for a mere product of manual craft. The prototype was a man such as Jacopo Strada in Venice in the sixteenth century. One of Titian’s most compelling portraits is of Strada, who, if not an art dealer by name, was a connoisseur and collector who managed to accumulate great wealth through the amassing of his collection and the advice he gave to others regarding their collections (see plate 1 below). Why does this portrait depict him looking away from the piece he is handling? There is a message here. He knows its value, both aesthetically and commercially. But he is not necessarily totally committed to its ownership. It could be traded—at a price.

1. Titian, Portrait of Jacopo Strada (1567): His hands hold the work of art but his eyes engage the unseen collector in a timeless image of salesmanship.

The importance of critics and art historians to the efforts of art dealers, an enduring alliance, dates from these times. The writings of Vasari, as we have seen, gave a framework to buyers’ understanding of the relative merits of the artists of the past. A practical instance of the sort of support that a dealer could derive from a critic is provided by our old friend Jean-Michel Picart, who sold a large number of works by Rubens to the Duc de Richelieu in the 1660s and 1670s. The fact that simultaneously the art historian Roger de Piles was plugging Rubens in a series of writings asserting the Flemish painter’s superiority over Poussin may not be entirely coincidental. Such a cooperation—between art dealer or collector and critic or art historian—to boost a particular artist is a commercial tactic not unknown in the years since.

The demand for supreme examples of art was still driven by princes and the aristocracy. In Germany, France and Spain the royal houses were acquiring major pictures as a statement of their power. In the seventeenth century they were joined for the first time by the British monarchy, as Charles I asserted himself as one of the great royal collectors. Sadly his progress went into reverse with the political difficulties that he encountered in the 1640s, ending in his execution. But for a time he was one of the biggest trophy hunters in Europe. His acquisitions were facilitated by Italy’s economic decline, which meant that many owners there were willing sellers of their treasures. The process by which royal houses and other aristocrats acquired art abroad opened up opportunities for skillful art dealers. Generally there were two options available to collectors who had the cash available but were unable to travel to make purchases. Either they made use of diplomats already posted to foreign cities where good art could be bought at reasonable prices, or they used personal agents and advisers—often underemployed artists—who acted for them with varying degrees of transparency, discrimination and scrupulousness.

To be British ambassador in Venice was an open invitation to become a de facto art dealer. At the beginning of the seventeenth century Sir Dudley Carleton, who held the post from 1610 to 1615, was one of the agents who facilitated purchases by the Earl of Arundel, the leading British collector who was instrumental in assembling the collection of Charles I. Carleton acted for others, too: In 1615 he bought fifteen Venetian pictures and a sculpture collection on behalf of the Earl of Somerset, from Daniel Nys. Nys was a wily Flemish art dealer who cropped up regularly wherever big art deals were being done in the first half of the seventeenth century, which meant that he spent a lot of time in Italy. Unfortunately for Carleton, his transaction hit the rocks when Lord Somerset fell out of royal favor and was unable to pay for the collection. This is the art agent’s nightmare: Carleton had already advanced the money to Nys out of his own pocket. There was no going back. An old hand like Nys was not going to unravel the deal. You can just imagine his regretful refusal: He was sorry, but he wasn’t a charity. Carleton, landed with the merchandise, threshed around for another buyer. In time he offloaded the pictures on to Arundel, but the sculptures were harder to shift. It was only when his diplomatic career took him to The Hague that he finally found a buyer for them in the shape of Sir Peter Paul Rubens, who was a shrewd operator in the art market. Carleton took payment in the form of works by Rubens himself, and in turn managed to place one of them, Daniel in the Lions’ Den, in the collection of Charles I. So the wheel of commerce turned.

Arundel, in search of a reliable man to operate for him in Italy, moved on from the diplomatic corps to the clergy, and recruited the Rev. William Petty. Petty, formerly tutor to the Arundel family, was dispatched to Italy at regular intervals in the ensuing years and rather took to art dealing. He acquired a number of major works for Arundel and for Charles I. By the 1630s Petty’s buying technique had taken on a distinctly experienced and cunning character. One of his strategies with pictures belonging to an Italian owner was bitterly outlined by a rival collector, the Duke of Hamilton:

He [Arundel] gives directions to Petty to make great and large offers to raise their price, by which means the buyers are forced to leave them and the pictures remain with their owners, he well knowing that no Englishman stayeth long in Italy. So consequents the pictures must fall into his hands at his own price; Petty being always upon the place and provided with monies for that end.

Eliminating your rivals by making higher offers, then waiting till they have left Italy before doing the deal at a rather reduced price is not a very becoming trick for a clergyman; but Petty was a clergyman with a head for business. And he did have a royal patron.

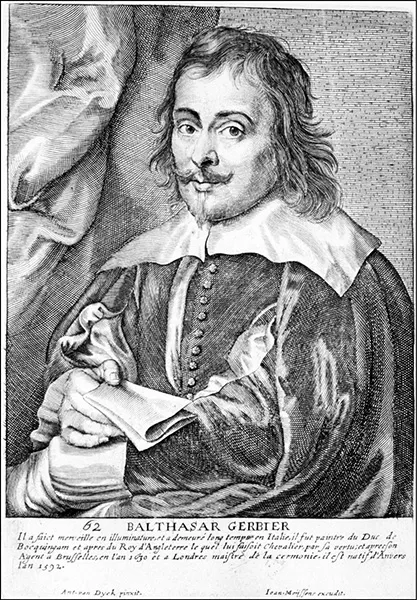

Balthazar Gerbier, prototype of the sweet-talking dealer.

In assembling his collection Charles I also made use of George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, an ardent collector who in turn employed as adviser and agent an operator possibly even wilier than Petty: Balthazar Gerbier. Gerbier was a Dutchman who trained as an artist but found more gainful employment in the art trade. In 1621 he went on an art-buying trip to Italy for Villiers and did particularly well in Venice. Once again it was with the help of the British ambassador, now Sir Henry Wotton, and the ubiquitous Daniel Nys. Gerbier managed to acquire the magnificent Titian Ecce Homo, for instance, for £275. In succeeding years he traveled to Spain and France on art-buying trips. He was ahead of his time as a dealer in the way he talked up the trophies he had laid hands on to his eager clients back in England. If it was sensuality you wanted, he could provide it: He spoke of “the most beautiful piece of Tintoretto, of a Danae, a naked figure the most beautiful, that flint as cold as ice might fall in love with it.” Or there was work of a more devotional nature, if that was your taste: “a picture by Michael Angelo Buonarotti [sic], but that should be seen kneeling, for it is a Crucifixion with the Virgin and St John—the most divine thing in the world. I have been such an idolater as to kiss it three times. . . .” But just to get across that he was discriminating on behalf of his clients, he also advised against “a picture of our Lady by Raphael, which is repainted by some devil who I trust was hanged.”

Gerbier knew how to ingratiate himself with those he worked for, writing to Buckingham in 1625 in an ecstasy of oleaginous sycophancy: “Sometimes when I am contemplating the treasure of rarities which Your Excellency has in so short a time amassed, I cannot but feel astonished in the midst of my joy. Out of all the amateurs and princes and kings, there is not one who has collected in forty years as many pictures as Your Excellency has in five.” And it was as well to remind his employer of the financial achievement, too: “Our pictures, if they were to be sold a century after our death, would sell for good cash, and for three times more than they cost.” It is an early instanc...