![]()

Solidarity Is Something You Can Hold in Your Hands

Interview with Torkil Lauesen and Jan Weimann

The interview was conducted by Gabriel Kuhn in Copenhagen in the spring of 2013. All footnotes in this interview by the editor.

KAK and the Parasite State Theory

How did you first get involved with KAK?

Jan: I was interested in politics because of my family. Both my mother and my father were in the DKP. Together with other students from my high school, including Holger Jensen, I started going to demonstrations against the Vietnam War. Holger was the first who had connections to KAK. There was also a student who was very interested in political theory. He showed me a series of articles that KAK had published under the name “To linjer” in Kommunistisk Orientering.1 Reading those articles was a revelation to me. They described convincingly why the class struggle had no perspective in Denmark and why it was necessary to support revolutionary movements in the Third World instead. As a consequence, I went from moral opposition to the war to theoretical study and activism. KAK’s ties to China, which were still intact at the time, weren’t that important to me. I was mainly attracted by the parasite state theory, and in 1968, I joined the Anti-imperialist Action Committee.

Torkil: I first heard about KAK in 1969. I went to a boarding school in Holbaek, about 65 kilometers from Copenhagen. There was a fellow student, Kim, who was a Maoist. He was a KAK sympathizer and explained Marxism, imperialism, and the parasite state theory to me. It all made perfect sense, and I could recognize much of what he said in everyday life. The theories seemed to explain the world very well. It was obvious that the living conditions of European workers were very different from those of workers in the Third World.

One day, Kim invited Holger to come and talk to us. Holger arrived on his East German motorcycle with short hair and clean clothes—not the typical appearance of young leftists at the time. I was impressed by his commitment and sincerity. In 1971, I joined KUF.

How did KUF relate to KAK?

Jan: KUF was sort of a recruiting ground for KAK. While KAK focused on theory, KUF was more action-oriented. KUF always had more members, too, and at times there were modest attempts at challenging the dominance of KAK—but Gotfred Appel always kept things in check.

How did the Anti-imperialist Action Committee fit in?

Torkil: It provided an arena for direct action. It was quite open and a testing ground for potential KUF and KAK members.

How much influence did Appel have on KUF’s journal, Ungkommunisten?

Jan: Not that much, actually. The journal was not censored by Gotfred, if that is what you’re asking. However, he made it very clear when something was published that he didn’t like.

And his role in Kommunistisk Orientering, KAK’s journal?

Jan: That was basically his own project. At the same time, one must not underestimate the role of Ulla Hauton, which I think many of us did in the 1970s. She always read and commented on Gotfred’s texts and he took her criticism very seriously. The fact that many of us never fully understood the relationship between Gotfred and Ulla certainly contributed to KAK’s end in 1978.

In 1972, KAK also founded TØJ til Afrika. How did this project relate to KAK, and how many people were active in it?

Torkil: Nationwide, there were between fifty and sixty people active in TTA. Some only wanted to support liberation movements, others moved on to join KAK. We usually referred to TTA members as “sympathizers.”

In a nutshell, what made KAK unique within the left of its time?

Torkil: That certainly was the parasite state theory developed by Gotfred Appel.

What led to the theory?

Torkil: In the 1960s, Gotfred had a Maoist perspective. Many KAK members were sent to work at big companies such as the shipyard Burmeister & Wain, the machine manufacturer FLSmidth, and Tuborg Breweries. The intention was twofold. First, KAK members should study the living conditions of the workers. For example, was it a problem for them when their children needed new shoes or had to go see the dentist? Second, KAK members should try to mobilize the working class on a “nonrevisionist and anti-imperialist” basis. This proved extremely difficult. There was no “single spark that could start a prairie fire”—everything seemed pretty damp.

So, the parasite state theory was a result of KAK’s failure to mobilize the working class?

Jan: No, that would be too simple. It was based on studies as well. KAK members knew how high the living standard of the Danish working class was, and we were familiar with Lenin’s writings on the labor aristocracy. There was both an empirical and a theoretical angle.

Torkil: Marx and Engels also wrote about the relationship between the English and the Irish working class and illustrated how an imperial working class treats a colonial one. The parasite state theory clearly had reference points in classical Marxism.

Another important influence were ideas formulated during the Chinese Cultural Revolution. Lin Biao, for example, described a revolutionary situation as peasants surrounding towns, which, on a global scale, translated into Third World nations surrounding the imperialist ones …

So, if you knew all this, why were KAK members send to the factories?

Jan: KAK was still a Marxist organization and the industrial proletariat is central to the Marxist concept of revolution. You didn’t want to count out the working class that easily. So, instead of just drawing the obvious conclusions from our analysis, it still needed to be put to test. I would say that the infiltration of the factories was a final attempt to establish a politically productive relationship to the working class. But that didn’t happen. It even proved impossible to get workers involved in the Vietnam solidarity movement.

In 1969, KAK got into conflict with the Chinese leadership.

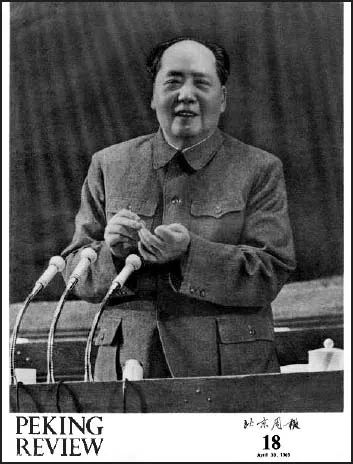

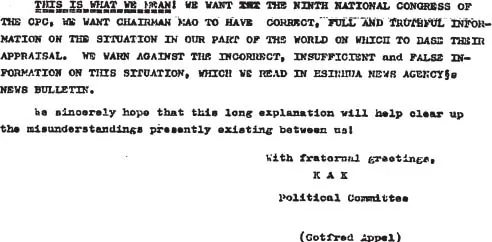

Torkil: That was a matter of analysis. The Peking Review published an article celebrating “gigantic revolutionary mass movements” in Western Europe.2 In response, KAK wrote a letter to the CPC and to the Chinese ambassador in Denmark, stating that this was a completely inaccurate perception and that we had empirical data to prove it. We basically said, “You use the same language to describe what is happening in Indonesia or Vietnam that you use to describe developments in France or Germany. Why? Those are two very different things.” As a result, the official ties to China were cut.

Cover of the Peking Review no. 18, 1969; the issue was dedicated to the Ninth National Congress of the CPC and contained the cited article by Lin Biao.

Final paragraph of a letter sent by Gotfred Appel to the Chinese Ambassador to Copenhagen, March 29, 1969.

The Vietnam War seems to have played an important role for KAK. How did your experiences from organizing protests against the war influence your politics?

Torkil: The protests confirmed where the Danish working class stood. Those who came to the demonstrations were young people and students, not workers.

Jan: This wasn’t unique to Denmark of course. In the U.S., antiwar demonstrations were even attacked by trade unionists. Our experiences in the factories were telling. When we handed out flyers about antiwar demonstrations, we got no response at all. The workers were interested in higher wages, not international politics. They were led by the representatives of the labor aristocracy, the DKP and the trade unions.

Torkil: The DKP, for example, controlled the Sømœndenes forbund, a seamen’s union. During the Vietnam War, the union was quite happy to ship supplies to the American troops in Saigon, as long as its members had their wages doubled for sailing into high-risk zones.

What was the class background of KAK’s members?

Torkil: Both working class and middle class. My father was a ferry navigator and my mother a nurse. Holger’s father was a carpenter, Niels’s father was a bookkeeper. The standard of living of my family increased enormously at the end of the 1950s—we could afford a house, a car, and holidays in Italy and Spain.

Jan: My father was a firefighter and my mother worked different factory jobs. I have two older brothers, both of whom are craftsmen. I was the first one in my family to get a high school diploma.

Quite a few KUF members also held working-class jobs. Peter Døllner was a carpenter, Holger Jensen a firefighter. Gotfred Appel drove a taxi for a few years, before KAK provided a modest salary for him and Ulla.

Let us continue with KAK’s history: once it was clear that the working class of the imperialist countries no longer qualified as a revolutionary subject, you turned to the masses of the Third World. Is that correct?

Jan: Our reasoning can be summed up in four steps:

- The capitalists of the imperialist countries made huge profits, super profits, by exploiting the Third World. Later, we used the theory of unequal exchange to further this analysis.3

- The superprofits were not freely distributed to the workers of the First World. Capitalism does not distribute anything freely. However, the superprofits created social conditions, in which workers, led by Social Democratic parties, fought for pieces of the pie. At times, it needed long and hard struggles to get those pieces, but during those struggles the labor aristocracy was formed.

- Over time, the interests of the capitalist class and the working class in the imperialist countries became more and more alike. The primary interest of the workers was to keep their jobs, and hence a strong capitalist economy, even if that meant fighting imperialist wars.

- As a result, the workers of the imperialist countries did not side with the workers and peasants of the Third World, but with those who gave them jobs, namely the Western capitalists. On a psychological and social level, the workers never were our enemies, though. Most individuals follow their objective interests.

So, how come some don’t? Like, apparently, you?

Jan: Of course there is always a difference between the situation of an individual and the situation of a class; or, between psychology and sociology, if you will. There is a possibility for individuals to act against the objective short-term interests of their class. But these individuals will always be a minority and even for them it needs special circumstances.

Torkil: The special circumstances in our case were provided by the unique situation at the end of the 1960s. Social protest movements in the imperialist countries, liberation movements in the colonized countries, and a widespread belief in a better world opened a window for us. And then there was KAK right here in Denmark, which provided a concrete possibility for revolutionary organizing. This was a strong cocktail.

But to be clear: as an individual you can never completely leave the objective conditions of your life behind. In 1974, we published a book, in which guerrilla fighters from Angola told their stories. It was called “Victory or Death.”4 That was not our reality. We could always make choices. Your socialization always catches up with you. Today I like to say that I can feel neo-liberalism running in my blood, too …

I’m sure we will get to neoliberalism. But let us stick to the “unique situation” of the late 1960s for a moment. You have mentioned “the belief in a better world” and the “concrete possibility for revolutionary organizing.” What did you expect to happen?

Torkil: Our view of revolutionary development was simple. In 1969-1970 there were about forty liberation movements active in Latin America, Asia, and Africa. The Vietnamese struggle was heading towards victory, and it looked good for many others as well. The rhetoric of most movements was anti-imperialist and socialist. They vowed to put an end to capitalist superprofits. This opened up the prospect for a fundamental crisis of capitalism with huge effects for both the capitalist class and the working class of the imperialist countries, which, in turn, promised to create the necessary conditions for a global uprising. What can I say? We had a very deterministic view of history.

Jan: We basically considered the Marxist analysis of capitalism’s necessary downfall to be a natural law. We were very scientifically oriented. Our positions were based on social study and economic analysis, not on psychology and wishful thinking. Our tools were investigation and reflection. We wanted to identify the laws that would lead the system into a severe crisis. Whether we ever achieved that is a different question.

Torkil: On an organizational level, the goal was to form a group able to understand the historical process and act when it became necessary. That was the purpose of KAK. We did not have a detailed analysis of what would happen in ten or twenty years, but we were convinced that we needed to be prepared for action. We wanted to prepare the future revolutionary party, and supporting liberation movements was a way to speed up the revolutionary process. Essentially, we were pursuing two things at the same time: one, building a strong organization; two, supporting liber...