![]()

1

The New Socialist Countryside Mode of State Intervention in Tianjin

The story starts from a town, named Huaming town. Huaming town is not simply an ordinary town located in Tianjin – it has another identity as a national-level strategic development zone.

The strange thing is that Tianjin is not the only strategic area for north China, so it is not immediately clear why Tianjin was chosen rather than other northern cities. Nor is it obvious why Huaming town was chosen by the Tianjin municipal government for development and urban expansion. In particular, the motivation behind scaling-up the project to national level, which meant establishing Huaming town as a national model of state-led urbanization in China, is not clear.

In order to understand these strategic decisions, it is necessary to consider the development background of Tianjin Binhai New Area, the process through which Huaming town was selected as a model village for the state-led urbanization project, as well as the transformation of the governance structure that is related to Huaming town.

Tianjin Binhai New Area

One of the most important drivers behind the establishment of the Tianjin Binhai New Area (TBNA) was the interaction between cadres from the central government and Tianjin municipal government, in which lobbying by the Party Secretary of Tianjin to the then-Premier Wen Jiabao, and the latter’s personal ties to Tianjin, were key factors.

The primary development idea of TBNA dates back to 1986 when the Tianjin municipal government established the TEDA – Tianjin Economic Development Area. However, the national development strategies focused on the south, west and central regions of China in the following two decades, including projects such as the Shenzhen Economic Development Zone, Western Development in 1999, and Rise of Central China in 2004.1 It was not until 2002 that the Party Secretary of Tianjin, Zhang Lichang, was elected as a Politburo member and invited central government cadres to visit TBNA, including the then-President Hu Jintao and Premier Wen Jiabao.2 Moreover, Premier Wen had personal ties with the region, as he was born in Tianjin and attended Tianjin Nankai High School. The development plan of Tianjin, the Overall Urban Development Program of Tianjin (2004–20), was approved by the State Council after Wen’s visit in 2005, and the State Council then went on researching the development plan for TBNA.3

TBNA is now a multi-layer entity composed of nine functional zones, two ports, nineteen sub-districts, seven towns, two districts and one administrative committee. The administrative reform since 2009 abolished the previous Tanggu, Hangu and Dagang districts, but the Dongli and Jinnan districts, partly occupied by TBNA, remain. Administrative districts are local governments, reporting directly to the Tianjin municipal government. Sub-districts (

jiedaobanshichu,

were formed from the previous villages, with some integrated into others, at the same administrative level as villages. In addition, Tianjin Port and South Tianjin Port were subordinated to the Tianjin State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) and run like a state-owned enterprise.

4 The nine functional zones are as follows: Advanced Manufacturing Zone, Airport-based Industrial Zone (AIZ), Binhai High-tech Industrial Development Zone, Seaport-based Industrial Zone, Nangang Industrial Zone, Seaport Logistics Zone, Coastal Leisure & Tourism Zone, Sino-Singapore Tianjin Eco-City, and Central Business District.

Model villages and precedent Xiaojinzhuang model

History repeats itself. A similar story happened forty years ago in the village of Xiaojinzhuang in Tianjin, which was set up as a model village due to the interaction between central leaders and Tianjin municipal leaders. Dating back to 1974, during the Cultural Revolution period, Mao’s wife Jiang Qing, then Minister of Culture, promoted an anti-Confucius campaign against political enemy Lin Biao. Tianjin municipal cadres encouraged Jiang Qing to visit after identifying Xiaojinzhuang as a model village for Jiang’s campaign, bringing Xiaojinzhuang to the attention of national-level politics.5

Xiaojinzhuang was a village located in the north of Tianjin, 30 minutes’ drive from Baodi county. After the difficulties in promoting the campaign in another larger village, where farmers were unaware of Confucius’s works and unmoved by the campaign, Tianjin municipal cadres thought a smaller sized village would be easier to control, so they encouraged Jiang to visit Xiaojinzhuang.6 For the farmers, a visit of a central leader, particularly Mao’s wife, was an honour. Wang Zuoshan, the then Xiaojinzhuang Party Secretary, hosted the visits of Jiang and other central cadres, and promoted the Cultural Revolution to demonstrate his loyalty. He was promoted to county level, even becoming a standing committee member of the Fourth National People’s Congress in 1975.7 To impress Jiang, Wang and the villagers engaged in poetry writing and opera singing, instead of farmwork.8

The fall of Jiang Qing and the Gang of Four, as well as nationwide decollectivization programmes, meant that Xiaojinzhuang missed its chance to transform into a prosperous village.9 Studying this historical case offers us insights into the contemporary case of Huaming town on points we might not otherwise notice. First, similar to Xiaojinzhuang, Huaming town in Binhai New Area is also next to Beijing, the centre of political power; second, the Xiaojinzhuang case shows the important implications of cadre motivation on village development; third, the Xiaojinzhuang case also highlights the relationship between the upper and lower levels of local states, especially the consequences of a top-down only approach to village governance for the livelihoods of farmers. Although development of TBNA was promoted by Tianjin municipal cadres, the transformation of Huaming town is part of the expansion of the development area, and the expansion of the Tianjin urban area has incorporated both labour and land in Huaming into the development zone.

The speedy transformation of Huaming town

Development of Huaming town was under the leadership of the then-Tianjin-mayor Huang Xingguo. The reason behind choosing Huaming town as a model for state-led urbanization was in response to the demand for land in the AIZ, which is an integrated function zone of TBNA. The pace of transformation of Huaming town from a small rural town of suburban Tianjin to a model town of state-led urbanization was extremely rapid, not only in terms of the transformation of the built environment and the industrial cluster but also in the changing livelihoods of rural residents. The relocation of the rural residents, as well as the transition of their productive activities, lifestyle and leisure activities altogether took two to three years.10 The transition has been multifaceted, with the built environment transformed from dispersion to concentration, and the industrial layout from agricultural to non-agricultural.

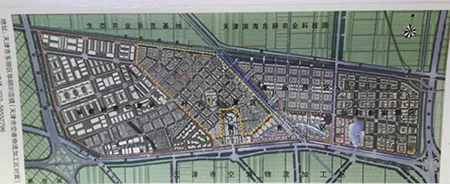

Huaming town is a sub-district-level town in Dongli district, which has nine sub-districts in total. Huaming town used to contain fifteen villages. After resettlement, the villages were displaced into one resettlement community (See Figure 1.1). Moreover, the village committee administration was abandoned and replaced by a newly founded urban neighbourhood committee, appointed by Dongli district. Huaming town was re-ranked at sub-district level, managed directly by Dongli district. After restructuring of the administration, the village committee was reserved temporarily and co-existed with the newly established urban neighbourhood committee, participating and cooperating with the urban neighbourhood committee in managing the daily operation of the new urban neighbourhood and shareholding reform. It is Dongli district, a county-level local state, that is responsible for identifying investment opportunities, governance restructuring and implementing other plans from Tianjin municipality.

Figure 1.1 Huaming town functional zones map. (Source: Huaming town brochure.)

Members of the resettlement committee expressed in interviews that they explained the resettlement process to villagers door-to-door and face-to-face before resettlement began. However, not all villagers agreed with the resettlement committee’s statement. While some expressed their expectation for a clean and neat urban living environment and reckoned that resettlement had improved their living conditions, particularly as it satisfies their demand for new housing, others were dissatisfied with how they were informed about the process. Some resettled farmers considered the resettlement process to be opaque, and complained that they were only passively informed and involved, which is reasonable given the short timeframe of the resettlement project. As one female villager in her late 40s with no urban skill-set said, ‘We ordinary villagers did not realize what was happening while resettling, and it was too late when we became aware what was going on: the new apartments were all allocated. Now our status has changed, we lost our farming land and got no money.’11

The new Huaming town resettlement committee

The new Huaming urban neighbourhood committee is a resident self-managing organization with one set up for every 3,000 households; committee members are elected by residents. The committee is composed of four offices. The Party politics office is responsible for the organization of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) governance work, task assessment, military, and women-related work. The economic development office handles economic planning, attracting investment, accounting and auditing. The social work office focuses on managing social welfare and charity, culture, hygiene and disabled people assistance. And last, the urban governance office oversees security, environment, food safety and Huaming town street governance (see Figure 1.2). The committee has four governors who are previous town-level and district-level cadres, responsible for the four departments, and the other five to nine committee members.

Figure 1.2 Huaming town new urban neighbourhood committee. (Source: author’s own diagram.)

Apart from the new urban neighbourhood committee, Huaming town also established neighbourhood and residents team and asset management companies. As for the neighbourhood and residents team, every eight to eleven buildings (around 300 households) is one neighbourhood; and around 30 households comprise one residents team. The head of the teams are elected by each neighbourhood and residents’ team.

As for the asset management company, each village established one company, making fourteen in total. For example, in the case of Guan village, it had thirty-six shareholder representatives and six investors. The shareholder representatives were selected via democratic procedure, where every ten households recommended one representative, to make up the thirty-six shareholder representatives. The asset management companies asked Huaming town government to manage a part of their assets, where the Huaming town government gave profits back to the company and the company shared them with individual villages. In this way, individual farmers’ shareholding income came to depend on the assets of the asset management company with which they are associated, i.e. their previous village membership. For instance, in 2013, dividends for farmers from the former Guan village were 8,000 yuan/person per year but only 1,000 yuan/person for former Huzhang villagers. This was mainly due to the fact that the Guan village asset company had assets of nearly 0.9 billion yuan; in comparison, Huzhang village asset company had assets of around 15 million yuan. This big difference in assets can be attributed to each village’s possession of assets before resettlement, which was a result of different economic development.

Carrying out the resettlement plan in Huaming town

In carrying out the grand development plan in Huaming town and establishing Huaming as a national model, the challenge of livelihood risks,12 stresses and shocks lay in the use of land and coverage of the cost. The Tianjin municipal government approached the development through ‘land balance’ and ‘capital balance’ policies. The major focus of the policy guideline was to make sure the new urban assets distributed to villagers was equal to the value of their previous possession of rural land, and the funding for the urbanization project was abundant.

‘Land balance’ indicates the balance of increasing urban construction land and decreasing rural construction land. Since 2005, this was implemented in Huaming town, where the household responsibility system was retained and the total amount of arable land kept the same. In Huaming, the land balance

concerns rural construction land (12,000

mu) rather than farmland. In the implementation of the state-led urbanization project in Huaming town, the increase of urban construction land matches the decrease of rural construction.

13 The other initiative, ‘capital balance’, represents the funding model of Huaming development, via bidding at auction (

zhao pai gua,

The development project was funded mainly by revenue from operating the land; led by the real estate developers, this was where rural residents moved into apartments first and real estate developers collected the revenue from business rental income from the AIZ. According to the plan, the cost of construction amounted to RMB 3.7 billion yuan, which is covered by the RMB 3.8 billion yuan revenue from the corporate tax and rents paid by companies in TBNA. However, in reality, sufficient income has not yet been generated to cover the cost, and the RMB 2.2 billion from the Development Bank still needs to be repaid, of which RMB 400 million should have been repaid in 2008 and RMB 600 million in 2009.

14To make this plan work and achieve ‘capital balance’, the industrial cluster layout in the AIZ needed to be restructured from agricultural industry to non-agricultural sectors in order to generate rent. Compared to the agricultural sector, the manufacturing and R&D sectors generate more return, as well as, in theory, streams of employment for the resettled farmers. On the other hand, to achieve ‘land balance’ and the transition of rural construction land to urban construction land, land reorganization was required, consolidating dispersed land and updating its administrative status. However, the decision-making structure within the TBNA is complicated, and conflicts exist in the reporting hierarchy. This is due to the overlapping of functions between administrative departments, particularly between the TBNA and each independent district, and between the central government and Tianjin municipal government. Although the administrative structure was reformed in 2009, where the previous Tanggu district, Hangu district and Dagang district were abolished, the two districts that were preserved – Dongli district and Jinnan district – now partly overlap with the TBNA not only spatially but also in terms of administrative governance.

Before the administrative reform in 2009, TBNA Administration Committee was simply a coordinating body, subordinate to the Tianjin municipal committee and Tianjin municipal government, and without its own fiscal budget. After the administrative reform, the TBNA Administration Committee gained administrative power over the districts in its administration. However, as Do...