![]()

CHAPTER 1

What Thing Is This?

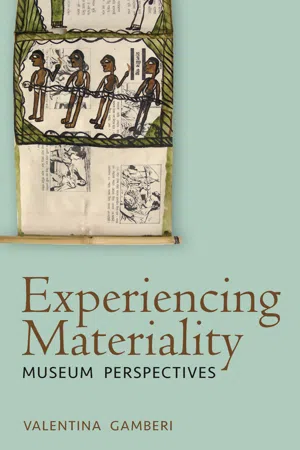

Indian Storytelling Scrolls

From the Things Themselves!

Everything starts with a material artefact. If we continue the Heideggerian image of the blue jug, to investigate the multifarious engagements between the human and the nonhuman within museums, it will be necessary to understand artefacts first. This chapter investigates the functions, meanings and ways of interaction of two storytelling scrolls, the pats and the paṛs.

Scholars, especially in the field of anthropology, also begin their narratives from the ‘original context’ of an artefact, to then emphasize the process through which it enters into contact with different human actors. They also address how the fluctuant semiotic of artefacts can radically change if it intertwines with heterogeneous contexts of usage. The volume edited by Appadurai, The Social Life of Things (1986), has played a central role in disentangling things from a pure Marxist framework according to which they are just products made for a demand. Thereby, the volume shows how material value is subjected to complex social judgements and projections. Davis (1997), in particular, talks about ‘interpretative communities’ or ‘communities of response’. For instance, a religious statue can contemporarily be seen as a work of art or an object of devotion according to the different communities – that is, groups of people who identify common values to use the thing in a certain way – that enter into contact with it. Steph Berns (2017b) defines common expectations and values as the ‘cultural/spiritual baggage’ of humans.

Experiencing Materiality as a whole investigates whether museum spaces manipulate religious values and religious responses. According to Kopytoff (1986, 73), museums are places where the material artefact is singularized, that is, secluded from the hands that normally transpose it from different contexts of usage and meaning-making. Let us imagine, for instance, the favourite pen of our great-grandfather, which has been given to us by our grandfather on a special occasion. For our grandfather, this gift could be a way to express to us his memory and love for his father. For us, conversely, it is a way to trace the different stories of our family. The pen passed through its usage by our great-grandfather to being an object of intimate memories of our grandfather. We can, in our turn, decide to use it as a fortune amulet for our exams, or keep it in our wardrobe imagining a moment in which we will give it to a particular person with whom we want to have a deep connection. If we decide to give it to a museum, this passage from hand to hand is interrupted. Disjointed from the accumulation and expression of different givers’ subjectivities, the pen can reveal to us different aspects that render it unique. In other words, the thing can be admired for its uniqueness, transformed into a sacred, non-ordinary thing. This uniqueness, according to Thiemeyer (2015), can vary depending on the different displaying techniques that emphasize the unique feature. For instance, our inherited pen can provide testimony or recollect the instant of a historical event – if we imagine our great-grandfather as a politician who signed a crucial treaty. It can also exemplify a specific kind of metal forging peculiar to the period of our great-grandfather. Therefore, we can put it within a series of other pens or metal works to visually trace the historical evolution of metal forging. We can also singularize the pen, put it in a single cabinet and play with light and darkness to signal its historical preciousness.

I argue, however, that in following Kopytoff’s biographical approach we can run the risk of dismissing ambiguous and fuzzy traces of values and embodied responses that do not fit with the conventional, usual treatment and consideration of a museum thing by a community of response. Our pen, for instance, can stimulate an artistic composition for an artist who sees it behind the glass of the cabinet, or convince an able thief to steal it and bond it with other metal substances to produce an amulet, use it for a scientific experiment, or some other purpose. Certainly, there is a form of control over the pen, but it is also true at the same time that the pen itself can guide or evoke particular and disparate uses.

In this chapter, I suggest analysing the ‘original context’ of the scrolls in order to reflect on their possible potentialities – on a theoretical, practical and methodological level – in the following chapters. Rather than viewing the ‘original context’ as the ideal way in which the scrolls must be used, I embrace the ethnographic literature on them as a way to address questions to readers and, possibly, to understand how and why curators have operated in cataloguing or displaying them.

Indian Storytelling Scrolls: An Overview

Indian painted scrolls used for storytelling ‘can be traced back through literary evidence to at least the second century BC and are known to have existed almost all over the subcontinent’ (Jain 1998, 8), and currently exist in Rajasthan, Gujarat, Bengal, Bihar and also in Deccan (ibid.). The scrolls’ stories are usually hagiographies, chronicles of ancestors and other deceased persons (ibid.). Furthermore, it is believed that the audience can spiritually benefit from the process of storytelling. For instance, the Garoda storytellers (from Western India) wander from village to village in what is called jatra, which means pilgrimage (ibid., 76). The ritual dimension of storytelling is further strengthened by the fact that storytellers often have sorcerer-like or priestly roles and names through their storytelling performances. Bhopa, the Rajasthani storyteller, for example, means ‘sorcerer’ (McLain 2009, 54). Nevertheless, some scholars contest this term, as the bhopa has minor priestly functions and does not fall into trances.

More importantly, the painted scrolls are considered shrines of the deities because of darśan. Darśan is both a piece of theoretical knowledge and individual experience (Grimes 2004, 531), as either a religious practice (contact with the divine) or an essential part of the pūjā or the worship of deities by means of offerings (Scheifinger 2009, 277). Consequently, the material representation of the deity is considered to be its incarnation, and so is treated as a human being. In the past, in the region of Deccan, ‘When an old scroll was badly damaged, it was cremated and immersed in a river like a dead person, and all the Hindu death ceremonies were observed’ (Mittal 1998, 58).

Examples of the connection between storytelling performances and scrolls and the creation of a ritual space are the storytelling boxes called kavad in Rajasthan and the murals related to the local god Pithoro in Gujarat. The kavad is a portable wooden box used in Mewar (Rajasthan), which is painted with sequences of religious and mythic stories. The origin of the word is related to an episode in the Ramayana, which is about Shravana Kumara carrying his blind parents on a pilgrimage on his shoulder ‘in order to restore their sight’ (Sabnani, 1989, 95). From this epic account, the meaning of kavad ‘as carried on the shoulder’ is derived (ibid.).1 Storytellers of the kavad (kavadiyas) are said to be Shravana Kumara’s descendants, because they display the temple-like kavad to those who cannot personally visit the holy temples and sites, thereby granting them darśanic interactions and gods’ blessings (ibid.).

The Rathva tribe’s mural depiction of the marriage of their god Pithoro is characterized in a precise way. The mural shows a bhalon, a vehicle by which Pithoro descends from heaven. In the original myth, this is a spider web, but in contemporary pictorial renditions the bhalon is shown as an aeroplane, as the Rathva started to see aeroplanes flying in the sky and thought of them as divine vehicles (Jain 1984, 39). In fact, the ritual installation of the mural uses two different expressions, specifically Pithoro behādvo, or ‘to get Pithoro seated’, and Pithoro lakhvo, or ‘to inscribe Pithoro’, indicating the act of painting (ibid., 44). These allude to a movement from one realm to another and prepare the ground for the trance possession of the badvo (or master of ritual), who starts to give names to each character depicted (or Pithoro vācvo – ‘to read Pithoro’ or ‘reading Pithoro’) after having received offerings and been ritually bathed (ibid., 56). The spirit who possesses the badvo is that of Pithoro’s birth father, Kuṇdu Rāno. After the sacrifice of the goats, the ceremony of the mural’s consecration ends with the sign made by the badvo’s knife in correspondence with the horses’ clogs. By ‘cutting the rope’ the agricultural forces represented by Pithoro’s mother can be spread in this world; hence the use of the rice grains offered during the ceremony and sanctified by the badvo in the fields (ibid., 58).

The anthropological literature refers to patuas and bhopas, as well as other Indian storytellers, as untouchables (Sen Gupta 2012, 66). This characteristic trait of storytellers is accompanied by the belief that painting is a sacred activity, the process of materializing the presence of the deities, of annihilating the distance between the ordinary and the supernatural realms. As Douglas claims in Purity and Danger (2009), the activities centred around the ritual and the sacred entail a double and contrasting set of responses. On the one hand, handling the sacred creates a separation or an interdiction of the ordinary, and so the roles of the social actors within the ritual change. On the other hand, dealing with the sacred also means the degradation of, or the possibility of degrading, the sacred, because of the common features of the actors engaged within the ritual. Materiality, thus, together with the adaptability of darśan to contexts different from that of the temple, gives storytellers an ambiguous status, in the tension between quasi-priestly functions and socially degraded roles. The ambiguity of storytellers is even more emphasized if we look at the fact that they create the possibility of reaching the deities for the lowest, mostly rural, social strata, whose access to the orthodox temples is usually restricted. Furthermore, darśan via storytelling scrolls justifies the cult of tribal or regional deities: by representing them in the scrolls, storytellers give to these minor deities the importance of those in the Hindu pantheon, as well as the deities of the other religions present in India, first of all Islam.

With this research, I want to explore the curatorial practices towards the pats and the paṛs, especially how darśan is perceived within museum spaces and re-elaborated by museum curators. Pats and paṛs seem to me particularly apt in adapting themselves in disparate contexts, not necessarily or explicitly linked to that of the ritual. For instance, Bengali scrolls are used nowadays as a means of political propaganda or of ethical education. Furthermore, the scrolls are adapted by the publishing house Tara Books and turned into graphic novels of various themes and cultural traditions.2 Paṛs are simplified and miniaturized for tourists in an extemporaneous and quite recent phenomenon. The broader chitrakatha tradition has been adopted by the comic book publisher Amar Chitra Katha in order to create a national cult of the hero and of Hinduism more generally. Darśan occurs, thus, in different ways, which demonstrate the overlapping of the sacred and the profane, as well as the resistance of religious materiality to the change of contexts. I was therefore curious to see how darśan continues its existence within museum spaces. At this point, then, a detailed introduction for readers to darśan is necessary.

Darśan

Distinct religious cultures have explained the act of looking.3 Looking is not an activity detached from the senses, but rather is how physical contact with the supernatural is established. Within Hinduism, a phenomenology of vision plays a significant role in defining the relationship between the worshipper and the god worshipped, as well as the divine nature, which can be represented and contained by the material object (Malamoud 1994, 263). The concept of darśan can summarize this phenomenology of vision.

Darśan is simultaneously a religious practice of seeing and the belief in the capacity of the material to be imbued with life. Darśan relies on the activation of images, a ritual operation by which the divine bestows life on the image so that it becomes or coincides with the entity it embodies. Since it becomes a simulacrum of a person or an anthropomorphized deity, the image has the power to re-enact the presence of a departed person. It is, therefore, connected with the funerary cults. As Freedberg (1989, 98) observes, the consecration demonstrates ‘the potentialities of all images’, in the fact that they already work before being consecrated. For instance, Indian comic books depicting Hindu deities, despite not being subjected to a ritual consecration, have been venerated as religious icons, and a new and subtle form of the cult has developed.

According to this religious understanding of the visual, seeing is not a passive and distant contemplation, but rather a form of engagement and relationship with the seen object, through the experiencing of its essences and properties, and through touching it (Hadders 2001, 32):

In English, the verb behold suggests this relationship between sight and touch. To see can mean ‘to want to touch’ or ‘to want to be touched by another,’ especially if one means ‘to expect,’ ‘to seek out,’ ‘to long for.’ The element of desire is evident in each, and that is one reason why cultured despisers of imagining from Plato to Calvin have commonly attacked the practice of making or admiring images: they invite the indulgence of desire. Seeing is dangerous because it leads to touching. (Morgan 2012, 111)

Deriving from the Sanskrit root drś (‘to see’), darśan includes vision, intuition and the ...