![]()

Part I

TRENCHES

![]()

Chapter 1

Legal Rubble

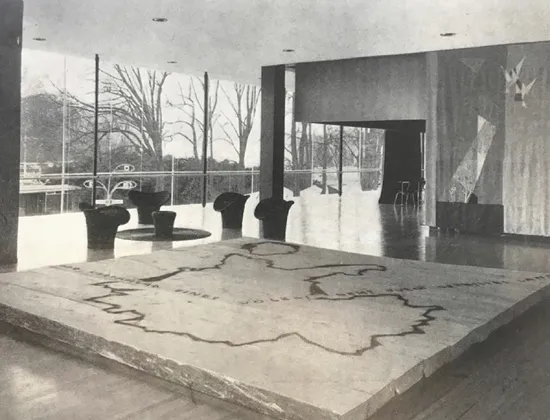

When the Brussels World Fair of 1958 opened, architects and designers praised the modern ‘non-ideological’ architecture of the West German pavilion. Yet this international acclaim was not matched with approval by West German mainstream media.1 Journalists from left-wing papers such as Vorwärts! (Forward!) to conservative tabloids like Bild and Quick lamented that the display of West Germany was not ‘nationalist’ enough and ‘the terrible effect of our home country’s partition upon the German people is forgotten’.2 The majority of the West German public thought that national division had not received enough attention in the curation of the exhibits and design of the pavilion.3 The art centrepiece of the West German pavilion belied this controversy. It stood in sharp contrast to the modernist architecture and allegations of an apolitical, industrial exhibition. Using a branding iron, the artist Josef Henselmann (1898–1987) had engraved the shape of the German Reich in its borders of 1937 on raw wood panels. The piece was titled ‘Divided Germany’ and carried the slogan, branded across the map, ‘The heartbeat of a people goes through a divided country’ (Figures 1.1 and 1.2).

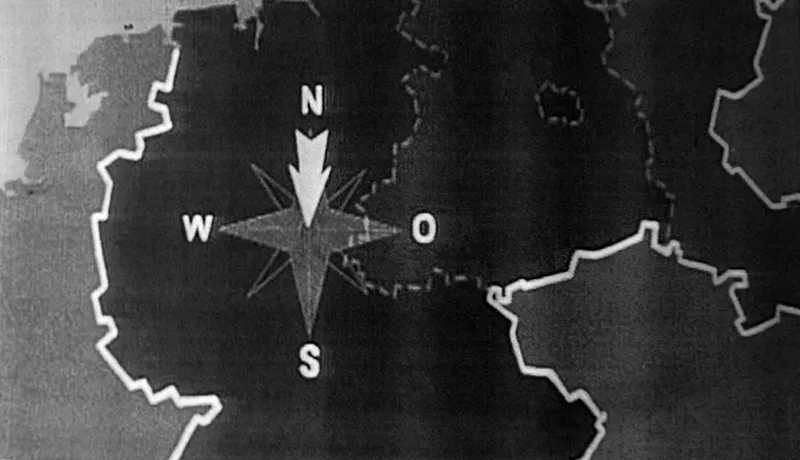

By 1958, legal scholars, politicians and high court judges had achieved an almost impossible feat. In the first decade after the end of the war, they had managed to persuade domestic and international publics of a tripartite division of Germany after 1945 under international law.4 This partition consisted of the FRG, the GDR and former Eastern territories that now formed parts of Poland and the Soviet Union. The legal construct of the ‘German Reich in its borders of 1937’ proved so successful that West Germans took it as an expression of reality by the late 1950s rather than a framework born in the early years of the Cold War. In 1958, it was an imagined reality that West Germans thought was only prevented by the Cold War military standoff on German soil. The fact that the victorious Allies had agreed at the Potsdam Conference in 1945 that Germany was to lose territory as a result of the war had long been brushed aside in West German public debates.5 From 1960 onwards, the eight o’clock news programme Tagesschau broadcast by the Arbeitsgemeinschaft der öffentlich-rechtlichen Rundfunkanstalten der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (ARD) even used maps of the German Reich in its borders of 1937 for the daily weather forecast (Figures 1.3 and 1.4). This daily representation of the lost nation-state engraved the prominence of the trope of a ‘still existing German Reich’ into everyday consciousness.

Figure 1.1. Federal President Theodor Heuss viewing ‘Divided Germany’ at the West German Pavilion, World Fair, Brussels, 1958. Source: Collection Expo 58, dept. Architecture & Urban Planning, Ghent University.

Figure 1.2. Josef Henselmann, ‘Divided Germany’, Brussels 1958 in: Werk und Zeit 7(6) (1958), 5. Photo: © Expo-Photo-Service.

Figure 1.3. ARD Weather Forecast Map, 1960. Photo: © Studio Hamburg (ARD), used with permission.

Figure 1.4. Remastered ARD Weather Forecast Map, 1960s. Photo: © Studio Hamburg (ARD), used with permission.

The mid-century’s strict separation between international law as rules that governed legal affairs between countries, on the one hand, and sovereign domestic legal systems, on the other hand, gave West German jurists the necessary room for manoeuvre to attack the Allies’ postwar settlement. Confrontations over the kind of human rights the UN should codify between the US and Soviet Union in the late 1940s and the superpowers’ simultaneous declaration that such rights should have no impact on established sovereign states reinforced this doctrine. In the wake of colonial powers’ attempt to re-establish unequal legal standards at the UN, West German legal experts promoted the argument that the Bonn government now represented German nationality and the German Reich’s sovereignty in its prewar borders. In the tradition of German nationality politics of the interwar period, the Bonn government pushed back at decolonized states such as India and asserted that the right of self-determination should not just apply for peoples under colonial rule, but all peoples – including Germans.6 They connected this claim to the rules of representation in international affairs. In the UN’s own logic of membership, one nation was represented with one seat. If the US, Britain and France wanted to support Bonn’s claim against the socialist East that the FRG represented the only legitimate German government, which they did by permitting the Bonn government official observer status at the UN in 1952, West German jurists and government officials intended to tie this international sovereignty to their Staatsrecht vision of postwar state sovereignty. In the eyes of the West German legal elite, this sovereignty inevitably took territorial shape in the German Reich prior to Nazi expansion.7

Under the cover of US rhetoric of a ‘roll back’ of communism, West German politicians thus disputed the postwar Allied settlement and the legal legitimacy of the GDR.8 Soon, the government also secretly financed rights activists to promote a human right to homeland to reclaim the territory lost in the Potsdam Agreement.9 Legal experts manoeuvred between international and domestic legal spheres, but hoped to keep them theoretically strictly separated in their legal arguments.10 They did so in the hope of keeping their East German counterparts out of the international law world as only one state could legitimately represent ‘Germany’ in the logics of postwar international law doctrine. The SED leadership meanwhile observed these developments from the sidelines. The Soviet Union’s temporary withdrawal from the UN in 1949 – following the frustration caused by the relegation of social and economic rights to secondary importance within UN politics and the accession of the ROC to the UN to represent China – left the GDR without access to international legal arenas outside the Eastern bloc after 1949.11 The GDR government thus first concentrated on the German-German legal contexts. The SED leadership chose the only immediate avenue available to attack and contest West German legal frameworks and instructed communist lawyers to make the case for the SED in front of West German high courts in trials against communists.

Managing Transition

At the end of the Second World War, the Allied powers shied away from decisively assuming full sovereign governmental powers in Germany. The Allies stated their intent to take over sovereign tasks in the Berlin Declaration of 5 June 1945 to begin their agenda of denazification but stopped short of annexation and taking over all governmental powers within Germany. Instead, they opted for occupation. This decision opened up room for competing legal interpretations of the status of German sovereignty and the rights of Germans.12 It was not an entirely unexpected situation. Already in 1944, there had been warning voices. The most prominent belonged to Hans Kelsen (1881–1973), the giant of interwar Austrian Staatsrechtslehre, who had urged the Allies to clarify the legal status of a defeated Germany. In 1945, he reiterated his warning when the Allied Control Council declared a mere belligerent occupation under international law. Occupation made it possible to treat German soldiers as POWs and prosecute the Nazi elite for their crimes and the Holocaust. Yet this Allied reluctance to take the necessary legal steps to create a firm new beginning of German statehood would result in complicated, incoherent and contested interpretations of Germany’s legal status.13 In the summer of 1945, Kelsen made a last attempt to warn the Allies: ‘No German puppet government should be allowed to operate under the control of the only true government, that is, the military government of the occupant powers. For any German government operating under the control of the occupant powers might be inclined to resort to sabotage’.14

New Cold War legal alliances formed. Between 1947 and 1949, the re-founded German Society for International Law passed several motions that reaffirmed the continued existence of Germany under international law.15 The German-Jewish émigré Francis A. Mann (1907–1991), member of the Legal Division of the Allied Control Council, aided the society by stating in the association’s journal that ‘Germany has ceased to be an independent sovereign state in the sense of international law, but continues to be a state’.16 Satisfying Allied demands for wide-ranging occupation powers, statements such as those by Mann paved the way for rhetoric that allowed for the claim that the German Reich’s state sovereignty had survived the unconditional surrender following Jellinek’s Staatsrecht dictum that separated the state’s legal existence from its social existence. The Berlin Blockade of 1948–49 helped West German legal experts to silence and shut out Kelsen’s position from German debates.17

Kelsen’s warnings went unheard. He only had a few supporters, including fellow legal scholar Hans Nawiasky (1880–1961), who returned to Germany in 1946 and introduced the basic rights catalogue to the draft of the Basic Law in 1948. Indeed, the majority of German legal scholars fiercely resisted Kelsen’s calls for a firm end date of the German Reich’s existence and the subsequent new emergence of German statehood.18 There were many reasons to favour a continued existence of the German Reich’s sovereignty under occupation. Millions of Germans were on the move or interned in POW camps. Reference to a sovereign state provided legal shelter of citizenship for those Germans, even if occupation suspended the sovereign powers of this state.19 It prevented Germans across the world from potentially becoming stateless. Such sentiments, however, could also be used in calls for a reversal of the Allied territorial settlement, which election campaigns of the immediate postwar years showed (Figure 1.5). As Bernhard Diestelkamp has highlighted, most German legal experts hoped to rescue as much of prewar Germany as possible in the years until 1949 and the instrumentalization of legal language seemed the most promising way of pressuring the Allies into agreement in an atmosphere of international rights codification between 1945 and 1948 when the UN proclaimed the UDHR.20

Figure 1.5. Election poster, 1947. Source: Archiv für Christlich-Demokratische Politik (ACDP), Plakatsammlung, 10-009-21.

West German legal experts were not alone in their rejection of Kelsen’s viewpoint. Scholars in the emerging GDR also opposed his argument, yet for different reasons. In East Germany, nascent theories of sovereignty focused on people’s sovereignty. Peter Alfons Steiniger (1904–1980), professor of public law at the Humboldt University Berlin, articulated one of the first legal arguments along these lines for the SED in 1947. Together with Karl Polak (1905–1963), who went on to become the doyen of GDR law until his death in 1963, the SED tasked Steiniger to head a constitutional committee and find answers to the legal questions of national self-determination and state succession. Steiniger firmly rejected the argument that the loss of sovereignty under Allied occupation equalled a Staatsuntergang (demise of the German Reich’s statehood). But he grounded this assumption in the existence of the German people, not including territory and state power as most West German scholars did. Following Soviet demands, East German legal scholars omitted territorial references in their deliberations on Germany’s postwar legal status.21 Steiniger and Polak nonetheless entered the legal confrontation with their Western counterparts based on the assumption that German sovereignty continued to exist. Their goal was to formulate a new constitution based on people’s sovereignty that should enable the building of socialism across all four occupation zones. The aim of building s...