This is a test

- 424 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In this first ever introduction to philosophy as a way of life in the Western tradition, Matthew Sharpe and Michael Ure take us through the history of the idea from Socrates and Plato, via the medievals, Renaissance and Enlightenment thinkers, to Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, Foucault and Hadot. They examine the kinds of practical exercises each thinker recommended to transform their philosophy into manners of living. Philosophy as a Way of Life also examines the recent resurgence of thinking about philosophy as a practical, lived reality and why this ancient tradition still has so much relevance and power in the contemporary world.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Philosophy as a Way of Life by Matthew Sharpe, Michael Ure in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Social Philosophy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

THE ANCIENTS

CHAPTER 1

SOCRATES AND THE INCEPTION OF PHILOSOPHY AS A WAY OF LIFE

1.1 The atopia of Socrates

The fifth-century Athenian philosopher Socrates (470–399 BCE) is widely acknowledged as the founder of the tradition of philosophy as a way of life (PWL). Unlike the pre-Socratic philosophers, on most reckonings, he focused exclusively on ethics rather than natural philosophy. Socrates’s ethical philosophy marked a significant cultural and intellectual shift away from pre-Platonic natural philosophy, which was widely conceived as ‘irrelevant to the good life’ (Cicero, Ac. 1. 4.15). For Socrates, philosophy’s most important topic was the conduct of human life. Socrates in Cicero’s words ‘was the first who called philosophy down from heaven, and placed it in cities, and introduced it even in homes, and drove it to inquire about life and customs and things good and evil’ (TD 5.4.10–11).1

That is to say, Socrates made the central philosophical question: ‘how can we live a good human life?’ Plato, whose written dialogues immortalized Socrates, depicted him engaged in discussions focused exclusively on this question. As Plato’s Socrates asserts, ‘There can be no finer subject for discussion than the question of what a man should be like and what occupation he should engage in and how far he should pursue it’ (G. 487e-488a). As we shall stress in this chapter, Socrates defined PWL against the dominant values of his Greek compatriots (9). The conception of PWL is borne from a conflict with the ancient Homeric ideal of the good life and what we might call the Periclean and sophistic sublimations of this ideal that shaped fifth-century Athenian democracy. Socrates’s bold, controversial claim is that only the philosophical way of life can deliver eudaimonia. In addressing the question of the good life, Socrates suggested that Athenians must choose between two incompatible alternatives: namely the philosophical or the political way of life, the practice of citizenship or the care of the soul. Plato’s Socrates spells out these alternatives in his dialogue with the fictional character Callicles2:

Is he to adopt the life, to which you invite me … speaking in the assembly and practising oratory and engaging in politics … or should he follow my example and lead the life of a philosopher; and in what is the latter life superior to the former? (G. 500c)

The central issue at stake in Socrates’s philosophy is the choice between the life of the philosopher and that of other non-philosophical citizens, including rhetoricians, sophists and even natural philosophers. Socrates maintains that to lead the philosophical way of life necessarily requires criticizing the norms and practices of Athenian citizenship. To borrow Nietzschean terminology, Socrates undertook a revaluation of all hitherto dominant values.3 Of course, we know from the trial and execution of Socrates (399 BCE) that his criticism of the moral failings and limits of Athenian citizenship and political practices incurred the contempt and displeasure of many fellow citizens who praised the virtues of civic participation.4 For the harshest of his critics, indeed, Socrates was not merely a voluntary exile, but a dangerous enemy of the people (misodemos). ‘What kind of wisdom can we call it,’ Callicles in the Gorgias reproves Socrates, ‘that “takes a man of parts and spoils his gifts” so that he cannot defend himself or another from mortal danger, but lets his enemies rob him of his goods, and lives to all intents and purposes the life of an outlaw in his own city’ (G. 486b-c). Socrates’s fellow Athenians valued ‘external’ goods like fame, honour, reputation and wealth above all else, and they identified active, agonistic citizenship as the principal means of acquiring these goods. From this perspective, Socrates’s philosophical way of life seemed to corrupt rather than educate citizens.

Socrates by contrast admonished Athenians that ‘the unexamined life is not worth living’ (Ap. 38a; 1.3 below). At issue is what has long been called the atopia of Socrates, his ‘strangeness’ in the eyes of his contemporaries, a strangeness which will continue to confound, fascinate or irritate commentators throughout the history of Western ideas. A veritable cottage industry of Sokratikoi logoi, mostly lost, emerged in the wake of his execution in 399 BCE, one feature of which involved recounting and celebrating Socrates’s odd ways of conduct, down to his rather fraught relationship with his formidable wife Xanthippe (10). The most famous, almost mythological dimension of Socrates’s atopia concerns what he calls his daimon or ‘inner spirit’, one which he tells us would counsel him against certain actions – perhaps a kind of semi-deity perceived by nobody else, perhaps Socrates’s way of describing what would later be called the conscience (Ap. 31c-d). Another dimension of this atopia are the famous Socratic paradoxes, which are as close to what we could term a literary genre that we can get when it comes to Socrates ((5) see 1.7 below). Plato also allows us to glimpse Socrates’s unusual conduct at the beginning of the Protagoras and Symposium, where his teacher is depicted as literally arrested by meditation on some thought. There is also Plato’s Alcibiades’s famous description of Socrates’s endurance, and seeming practice of some kind of contemplative spiritual exercises (3) on military campaign, in the later dialogue:

I remember, among his many marvellous feats, how once there came a frost about as awful as can be: we all preferred not to stir abroad, or if any of us did, we wrapped ourselves up with prodigious care, and after putting on our shoes we muffled up our feet with felt and little fleeces. But he walked out in that weather, clad in just such a coat as he was always wont to wear, and he made his way more easily over the ice unshod than the rest of us did in our shoes …. Immersed in some problem at dawn, he stood in the same spot considering it; and when he found it a tough one, he would not give it up but stood there trying. The time drew on to midday, and the men began to notice him, and said to one another in wonder: ‘Socrates has been standing there in a study ever since dawn!’ The end of it was that in the evening some of the Ionians after they had supped – this time it was summer – brought out their mattresses and rugs and took their sleep in the cool; thus they waited to see if he would go on standing all night too. He stood till dawn came and the sun rose; then walked away, after offering a prayer to the Sun. (Symp. 220b-d)

In this chapter, we analyse the key parameters of Socrates’s revolutionary invention of the persona of the philosopher, and of PWL. This includes his signature dialogic practice of the elenchus (3), his foundational call for philosophers to ‘turn inwards’ (5), paying primary attention to themselves as against externals (6), his description of philosophy as a care of the soul (7), its attendant ethical paradoxes (6), as well as his embodiment and advertisement of the new ideal of the philosophical sage (10). We can begin to understand the basic characteristics of Socrates’s mode of philosophical living, however [1.2], by comparing it with modern university philosophy (what is ‘first for us’, as Aristotle might say), and then with Socrates’ own rivals, the sophists [1.3].

1.2 A founding exception

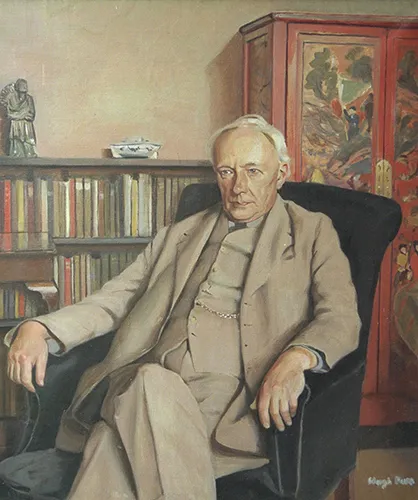

For contemporary philosophers, Socrates cuts a very strange figure (see Frodeman & Briggle, 2016). Socrates’s philosophy consists exclusively of his way of life. Unlike modern philosophers, he did not write books formulating, systematizing or defending theoretical doctrines. All that we know of Socrates’s philosophy derives exclusively from the writings of others, including the popular genre of Socratic dialogue or logoi sokratoi that arose among his disciples after his death. The principal ancient sources of our knowledge of Socrates are Xenophon’s Memorabilia, Plato’s Socratic dialogues and Aristophanes’s satire The Clouds.5 Rather than writing philosophical treatises, Socrates spent his life in the streets and marketplaces of Athens engaging in ethical dialogue with any persons willing to submit their lives and values to examination. We might visualize this difference by contrasting conventional portraits of two modern professional philosophers (Figures 1.1 and 1.2) with Jacques-Louis David’s famous neo-classical representation of Socrates (Figure 1.3):

Figure 1.1 J. Derrida. Jacques Derrida Portrait Session. RIS-ORANGIS, FRANCE – JANUARY 25. Jacques Derrida, French philosopher, poses during a portrait session held on 25 January 1988 in Ris-Orangis, France (Photo by Ulf Andersen/Getty Images). Source: Getty Images.

Figure 1.2 G.E. Moore, Reproduced with the kind permission of the Faculty of Philosophy, University of Cambridge.

Figure 1.3 Jacques-Louis David’s Socrates. Public domain. Sourced from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436105

The conventional representations of Professors Jacques Derrida and G. E. Moore, founding figures of so-called ‘postmodern’ and ‘analytic’ philosophy respectively, picture them as solitary, study-bound masters of book learning. If we judge by portraiture, how they live is irrelevant to their philosophy. Apart from a faint hint of the philosophical ‘seer’ in their penetrating, fixed gaze, neither portrait suggests that how these two professors live beyond the study has any philosophical significance. By contrast, already in antiquity, Plutarch, the first-century Greek biographer and moralist, nicely captures the figure of Socrates as the antithetical to ‘academic’, armchair philosophers:

Most people think … those are philosophers who sit in a chair and converse and prepare their lectures over their books; but the continuous practice of … philosophy, which is every day alike seen in acts and deeds, they fail to perceive … Socrates … was a philosopher, although he did not set out benches or seat himself in an armchair or observe a fixed hour for conversing or promenading with his pupils, but jested with them, when it so happened, and drank with them, served in the army or lounged in the market-place with some of them, and finally was imprisoned and drank the poison. He was the first to show that life at all times and in all parts, in all experiences and activities, universally admits philosophy. (Plutarch, ‘Whether an Old Man Should Engage in Public Affairs’, 26)

For Socrates, philosophy was a comprehensive mode of living that expressed itself in every facet of experience. ‘Through the centuries …,’ as Hadot observes, ‘and first of all in antiquity, particularly for the Stoics and the Cynics, Socrates was the model of the philosopher, and precisely the model of the philosopher whose life and death are his main teaching’ (Hadot, 2009: 121–2). For the Renaissance Neoplatonist Ficino, Socrates was ‘the antischolastic, a man who taught philosophy by his life and death, not de haut en bas from a professorial chair’ (Hankins, 2006: 348). In the nineteenth century, both Soren Kierkegaard and Friedrich Nietzsche would each be fascinated and vexed by Socrates, exactly as the avatar of a new form of life which each felt they needed to contest (Hadot, 1995: 148–51, 155–7, 165–70). However we assess the fact, Socrates exemplified the courage to live truthfully, and the serenity to die without fear or bitterness. David’s 1787 painting, The Death of Socrates dramatizes Socrates’s extraordinary self-mastery by sharply contrasting his philosophical composure in the face of his own death with the emotional agitation of his friends, disciples and even his guard (whom Socrates tells us that he had befriended).6 David’s portrait underscores that for Socrates’s followers it was his sage-like elevation above the ordinary fear of mortality that distinguished his way of life. ‘The image of the dying Socrates,’ as the young Nietzsche puts it (see Chapter 10), ‘the man freed by insight and reason from the fear of death, became the emblem over the portals of science’ (BT 15).

We cannot overemphasize the sharp contrast with contemporary professional, disciplinary philosophy which is represented by the fact that Socrates did not aim to formulate, teach or interpret theoretical doctrines. He instead aimed to exemplify the philosophical mode of life and engage his interlocutors in a particular spiritual exercise, namely the famous Socratic elenchus. By means of this spiritual exercise, as we shall see [1.4], Socrates sought not to inculcate theoretical doctrine, but to convert their souls or psyche. Socrates’s discourse, as Hadot explains, ‘disturbed them so much that they were eventually led to question their entire lives … Socrates sows disquiet in the soul … leading to a heightened self-consciousness which may go so far as a philosophical conversion’ (Hadot, 1995: 148). And this action of conversion, enabling and exemplifying it, just was the pre-eminent business of Socratic philosophy.

1.3 Socrates contra the Sophists

However, in inaugurating the new paradigm of PWL, Socrates’s main target was of course nothing like what we know as academic philosophy, a phenomenon whose first antecedents would only emerge after, and perhaps because of his passing. Socrates’s intellectual rival, alongside perhaps the poets of such centrality to ancient Greek education (Rep. X, 607a-b), was the highly politicized intellectual movement known as sophistry. We can therefore clarify his ideal of PWL by understanding his objections to sophistry. In order to do this, let us briefly sketch the sophistic political education that rose to cultural prominence in fifth-century Athens before turning to Socrates’s alternative philosophical way of life.

In Athenian democracy, rhetoric, or the technical art of speaking well, was a vital skill of citizenship. With the advent of the polis, as Jean-Pierre Vernant explains, ‘speech became the political tool par excellence, the key to authority in the state, the means of commanding and dominating others … The art of politics became essentially the management of language’ (Vernant, 1982: 49–50). To secure votes in the democratic Assembly or to win cases in the Athenian law courts, citizens had to strive to master the art of rhetorical persuasion. The power of sophistry to enable the trained orator to dominate the popular courts, Assembly and Council, as Plato’s Gorgias advertises in the dialogue that bears his name (G. 452e). Major sophists like Gorgias, Prodicus, Hippias and Protagoras moved to Athens to serve the educational demands of its flourishing democracy. For those who wished to master the art of rhetoric, Protagoras counselled that ‘there are two opposite arguments on every subject’. Protagoras’s ‘antilogies’ (opposing arguments) illustrated how on each question ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I: The ancients

- Part II: Medievals and early moderns

- Part III: The moderns

- Appendix

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index of Proper names of primary sources

- Index of concepts

- Imprint